Xenolanguages and Alien Life

Jenna Sutela and interspecies communication

Jenna Sutela (1983, Finland) works with words, sounds, and living media, such as bacteria and slime mold, to create experimental installations and performances that bring together biology, technology and cosmology. Sutela’s recent work explores interspecies communication, aspiring to connect with a world beyond our consciousness. Jenna Sutela’s Holobiont features in the programme of DEMO moving image festival. Holobiont considers the idea of embodied cognition on a planetary scale, featuring a zoom from the outer space to inside the gut. The video documents Planetary Protection rituals at the European Space Agency and explores extremophilic bacteria in fermented foods as possible distributors of life between the stars. Bacillus subtilis, the nattō bacterium, plays a leading role.

The idea that living beings are to be considered individual agents, whose positions in the cosmos are determined by specific hierarchies and taxonomies, is a belief that Western science and natural philosophy have developed for millennia since the age of Aristotle, reaching its climax during the modern age. Although this metaphysical and epistemological systematization of reality, based on the principle of distinction and individuation, has allowed for an incredible social and technological progress—at an increasingly higher cost paid by who or what has been excluded from it—the perspective of an irreversible collapse of the entire global ecosystem is now showing the unsustainability of the cosmological order constructed by the West through centuries.

Alien Life

Through her practice, Jenna Sutela examines those boundaries traced between different forms of living and non-living beings, making evident their total inconsistency. By adopting the point of view of organisms often overlooked and considered to occupy the lowest positions in life’s hierarchy, such as moulds and bacteria, Jenna Sutela explores their peculiar ways of behaving and interacting with the environment. In this way, she unfolds the actual complexity of those organisms, highlighting their fundamental role in the constitution of the cosmos that we, humans, inhabit.

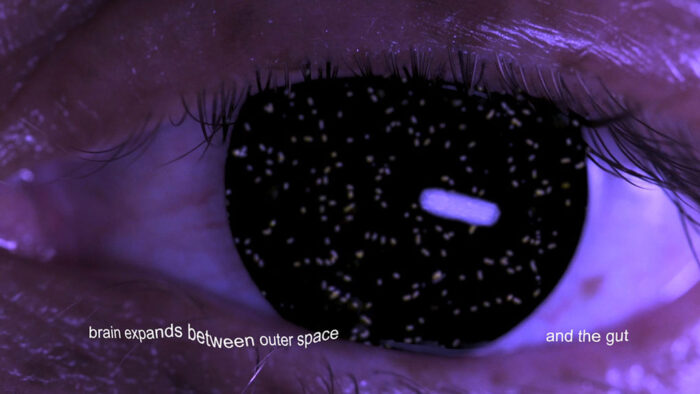

In her film Holobiont (2018), for instance, the bacterium bacillus subtilis becomes the agent that allows us to trace a red thread that connects our gut to the outer space. The bacillus subtilis is a bacterium that proliferates in our digestive system, but is also used by scientists to carry out experiments on life in the outer space, which allows us to speculate on its alien origin. The figure of the holobiont, an organism resulting from the assemblage of other organisms, thus eventually appears to coincide with the cosmos itself, implying the panspermia—seeds everywhere—the distribution of uncountable forms of life throughout the universe, which intersect and interact with each other, making the whole universe a living being with potentially infinite articulations.

The physarum polycephalum is another living organism on which Jenna Sutela focuses her practice and research. Despite being an elementary organism, the physarum polycephalum is able to challenge the supposed supremacy of human intelligence, by being capable of performing complex cognitive processes based on reasoning models radically different from the human ones. This is indeed the most successful way to challenge one’s pretension of absolute supremacy: relativizing its field and counterposing alternative models.

Emphasizing the existence of multiple forms of rationality, the supremacy of human intelligence appears to be limited to a specific rational model; a model based on processing information through multiple levels of abstraction, by deploying systems of representation and codification (language), as well as a high level of self-consciousness. Physarum polycephalum’s cognition instead operates without abstraction, without representation, and without consciousness.

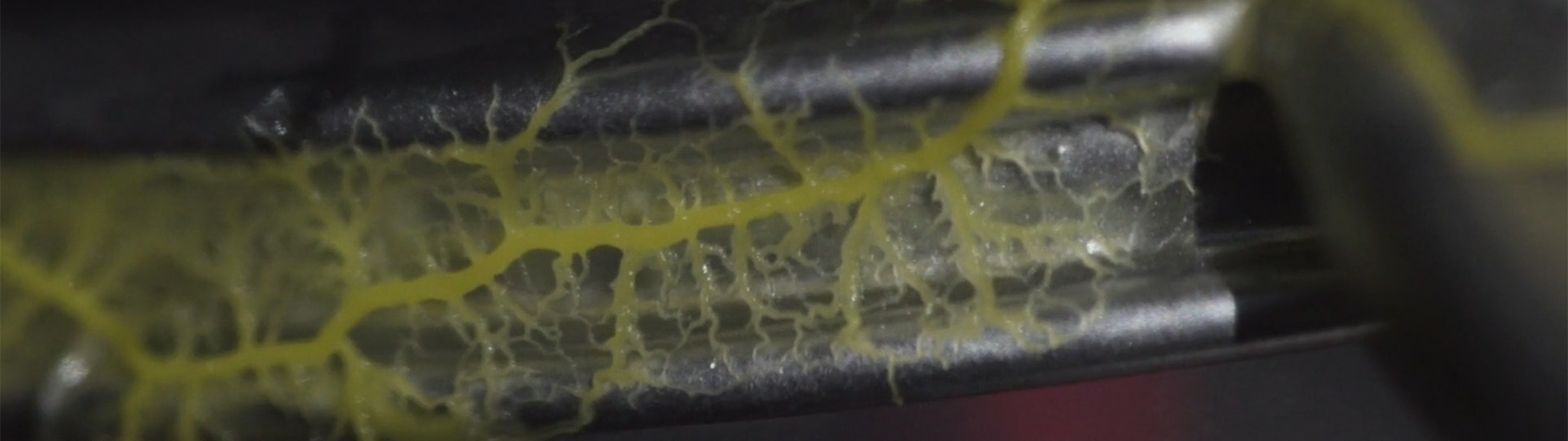

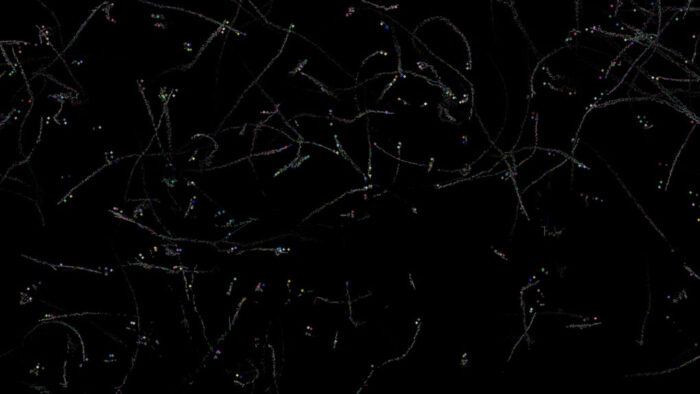

The physarum polycephalum is a single-celled organism, which multiplies into a bright yellow mass that spreads in multiple directions. The population of autonomous cells acts like a single being, moving and spreading with efficiency and coordination to find food and avoid light. Although it has no brain or nervous system, the group organism demonstrates an advanced spatial intelligence. Experiments conducted by the researcher Toshiyuki Nakagaki have demonstrated the high efficiency of the processes of decision making enacted by the physarum polycephalum.

Lacking a nervous system, this organism cognises without perceiving and thinking, or, rather, one should say that its sensing and cognition coincides with the expanding of its body. Physarum polycephalum’s ramified body immediately corresponds to its mind, as its movements and cognitive processes are fundamentally the same thing—the cruciality of the question of “what a body can do”, as Gilles Deleuze puts it, to investigate the possibilities of thinking, appears here in all its evidence.

Interacting with the physarum polycephalum through various media (moving image, performance, sculpture, and writing), Jenna Sutela highlights the absolute alterity of this organism in relation to our categories of life and intelligence. Besides, working with a living organism as an artistic material requires a high level of flexibility and openness to unpredictable results, as in the case of the sculptures From Hierarchy to Holarchy (2015) and Orbs (2016), which recreate a habitat structured as a maze where the physarum polycephalum can grow and proliferate, becoming an active element in shaping the artwork itself. The same approach is also adopted in her performances: inhaling physarum polycephalum’s spores before her Many Headed Reading (2016), Jenna Sutela turns her own body into the habitat hosting this alien form of life.

Xenolanguage

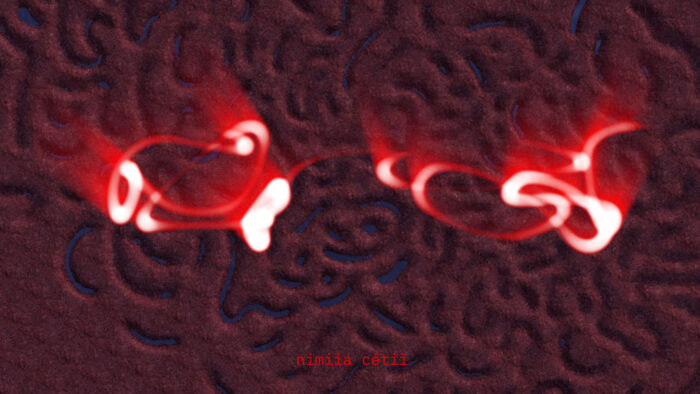

In order to challenge and deconstruct the ontological hierarchy on which the West has founded its culture and politics, which sees humans—the white man, to be precise—on the top of such hierarchy, new systems of machine intelligence, such as machine learning and neural networks, could also be valid allies in this struggle. In nimiia cétiï (2018), Jenna Sutela establishes a triangulation among artificial neural networks, bacillus subtilis bacteria, and the Martian language channelled by the medium Hélène Smith, in order to enable an “interspecies” communication, in which the human element intervenes only in a later stage to perform the language elaborated by those three agents.

The uncanny estrangement caused by a written and spoken language developed by three agents that are usually not considered to be capable of communicating through complex and articulated linguistic systems, makes evident the alien nature of all languages, including human ones. Yet language never completely belongs to the agents that produce and deploy it, as it always maintains a degree of autonomy and extraneity from its users. The awareness of this peculiar nature of language, very present in archaic societies, gradually disappears with the progress of the civilisation, in which language is eventually transformed into a mere intellectual faculty.

In his works, the linguist Louis Hjelmslev extensively accounts for the apparatuses implemented by pre-modern societies in order to connect the members of the community to their language. He describes rituals during which specific systems of signs are inscribed on the bodies of people through clothes and ornaments, as well as permanent alteration of the body, such as tattoos, scarification, and piercings. Yet the increasing “hypertrophy” of the subject, as Theodor Adorno puts it, occurred during the progress of Western civilisation, has turned language into one of the faculties of the rational subject, thus removing the gap between them.

Nonetheless, this distinction has frequently reappeared in philosophy and literature. From Socrates’ rejection of writing to Samuel Beckett’s poetics of the absurd, language has often been considered as a problematic alien agent. Although it constitutes the necessary condition for thinking and communication, language’s ambiguity also threatens the subject that deploys it, as it can never be completely controlled: thinking and communication are possible thanks to language, but also despite it.

To acknowledge the heterogeneity of an element so fundamental for the constitution of human subjectivity, such as language, means also to highlight the inherent incompleteness of the latter. Although, to embrace this precarious condition is also what allows humans to maintain a constant openness toward the outside and connect their existences to the ones of other beings. And it is exactly on this level that the work of Jenna Sutela develops, allowing us to navigate the dimension in which our existence appears to be inextricably linked to the ones of other living and non-living beings.