World/AntiWorld

On the history and futures of surveillance technologies

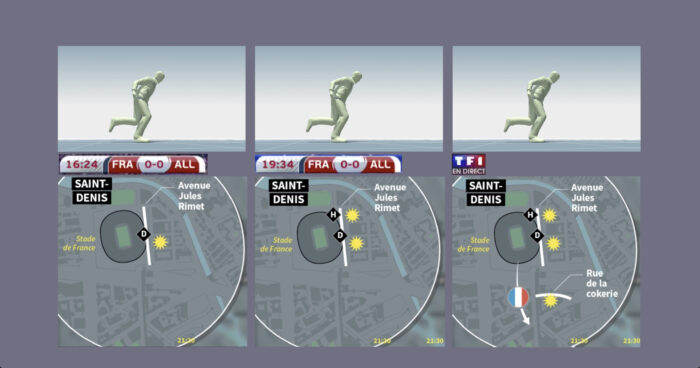

World-AntiWorld is a lecture-performance by Haig Aivazian, which grapples with the ways in which our selves are collectively and individually constituted and de-constituted by the intersecting gazes of law, capital and machines, Structured around the three explosions that occurred at the Stade de France in November 2015, the narrative of this lecture takes on the history and futures of surveillance technologies and the so-called subjects they construct. With a particular focus on the increasing difficulty to differentiate between populations of colonies, war zones, and ghettoes, or to clearly delineate the territorial boundaries between them, Aivazian looks at the preemptive and corrective regimes triggered by the back and forth passage between the state of law and the state of exception. The narrative is weaved in and out of the stadium, and told with the help of found online material, to present a world at once familiar and endlessly alien.

World-AntiWorld will be performed on November 21st, at 6:30pm, in the Aula Magna Regina (Guarini Campus) John Cabot University, Via della Lungara 233, as part of the Fall 2024 edition of the event series Digital Delights & Disturbances (DDD).

The DDD Event Series is organized and sponsored by the JCU Department of Communication and Media Studies, in collaboration with NERO and CRITT (Centro Culture Transnazionali).

More info and RSVP at [email protected]

How is military technology and cybersecurity re-invested in all aspects of daily life, from stadiums to airports?

Haig Aivazian: First we need to define what we mean by military technology, or what constitutes a technology. In my sense it is not simply machines in the sense of gadgets, gear, tech, or algorithms and models as such. A technology is any protocol in one realm that can engender a transformation in another realm. Namely it is a code in the discursive realm that can transform things on an ontological level in the material world.

So for instance, in response to your question I could say that the Iraq wars were instrumental in proliferating a whole series of technologies that were developed for and tested in a war zone, but that shaped the world at large beyond the presumed enclosure that is the war zone. GPS for instance, or the explosion of biometrics is even more apt. A technology that is accelerated during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan as a way to distinguish enemy combatants from civilians within the war on terror. And we see how this technology is then generalized and banalized as the standard for all forms of civilian identification, from passports to drivers’ licenses and so on.

But I would argue that beyond the specific tools used, it is more about the kinds of jurisdictions certain military logics might open. And without going on for too long and staying with the example of Iraq and Afghanistan and biometrics, the famous line the US military was using for their mass eye scanning, fingerprinting, photographing endeavors in Iraq was “to get on the other side of car bombs.” Meaning they were trying to develop predictive and preventive technologies to identify where the next car bomb was likely to be and when. This had to pass through a calculation of the kind of persons who would be most likely to enact such a thing. This predictive logic very quickly spread to be at the forefront of policing efforts in most big cities. More generally we can say that these technologies transform an entire population into potential threats, suspicious unless fully visible, known, with no possibility of anonymity.

The accumulation of maximal information and the use of machine learning to understand patterns and therefore better predict behaviors has also made its way and completely revolutionized sports. How it is watched, how it is played, how it is invested in, the betting economies it engenders and so on.

Here again I am more interested in the kinds of legal, market, security and other logics that are inaugurated in the (de)regulation of these technologies, rather than the specific technologies themselves. I can say more about this later, but for now it may be worth giving a few quick examples of specific tech that traverse back and forth from war zone to stadium. One is that the computer vision system that revolutionizes the data-ification and metrics boom in sports is adapted from an Israeli missile tracking technology.

Another example is that after 9-11 when the Pentagon adapted massive and constant video surveillance, via drones and other weapons, it turned to sports mega-broadcaster ESPN to better learn how to save and manage massive amounts of video data. We also know how Amazon and Google among so many tech giants provide cloud services for so much of Israel’s increasingly automated apartheid infrastructure.

And so in much of my work, I am just conscious of cohabiting with the ghosts that inhabit our technologies, whether they are the ghosts of countless Iraqis that were killed by The US war machine, or Palestinians who were the lab rats for Israeli surveillance and death distribution industries. I am conscious of how these ghosts haunt those of us who use these technologies or are teleported onto us when these technologies are applied upon us.

One of the things I want to do with my work is learn from these ghosts, to honor them, learn from them. I want to make work that can channel and talk to our dead.

And vice versa how much of the technology we use and consume everyday is related to (or produced by) war?

Here again, I tend to move away from the specific technologies and think more broadly about legal/extra-legal regimes that open up or close down depending on the approaches we take towards our technology.

What does it mean when a massacre is perpetrated by booby-trapping thousands of telecommunications devices like Israel just did in Lebanon? We know by now that this kind of state terrorism is always a justified exception in the context of a war on terror, but the manner in which this act weaponizes such a widespread and personal device, no longer simply as a spying tool but as a mini bomb in and of itself, opens up possibilities for new regimes of death distribution via various kinds of technologies.

Similarly, what does it mean when electrical and internet infrastructure is weaponized as an act of collective punishment, an act of blindsiding a whole population before bombing them to smithereens, as a way to starve them of basic needs in the lead up to starving them of food?

These are never isolated acts and open new forms of jurisprudence in relation to how various forms of administrations overlap and are exercised on populations whose humanity is a calculable variable. And whatever jurisprudence is established over an enclosure or particular population (war zone, colony, ghetto, prison, stadium, camp…) never remains circumscribed within them.

This movement back and forth between democracy and its enclosures, exceptions, excesses is what democracy is. There is no democracy without a place where its surpluses, that which does not fit into the category of democratic values, must be exercised.

What is the subject constructed by surveillance technology?

I don’t know. I think it is very hard to know. In one way we are and have always been technical beings, formed by our technologies, always. From the moment we externalize our memories with tools, with writing and so on. So I am not claiming that there is some pure unmediated self that we need to return to.

I also think that there are illocutionary commands, speech that functions as .exe files. So one question would be what kinds of subjects does a sentence like: “these are human animals” or “we are the sons of light and they are the sons of darkness” produce? Because clearly these words enact a new legal regime, where a whole population will suddenly be stripped of a series of legal benefits, rights, considerations, protections… and be exposed to relentless forms of degradation, devaluation, dehumanization, maiming, torture, mass killing.

How cameras and lights became tools of surveillance?

I think there are many histories of this. Histories that are uneven in various regions of the world like much of modernity. What I am interested in is of course the kinds of regimes of visibility and invisibility these technologies usher, but I also want to have a profound understanding of what socialities, imaginaries, poetries, solidarities, intimacies and so on these tools enable. What protocol has been enacted by that executable command and what organizations and categorizations does it enact within status quo taxonomies of what deserves life and what is undeserving.

I am interested in the histories of labor that went into the economies of producing oil, mineral spirits, phosphate, gas, electricity. The kinds of gigs and indentures they created, the kinds of ecosystems were created or decimated in the extraction of these materials.

I am also fascinated by how darkness becomes constructed in relation to light. How moral values are assigned to it, how demons, ghosts, sexual desires, crimes… inhabit the night.

But to return more specifically to your question, I think again from the onset, it is the regulation of artificial light that is the real technology. When in 17th century Europe for instance, in addition to requiring people to carry a lantern to identify themselves when out at night, installs street lanterns as a way to curb crime, it ushers in a new era in policing. Court records show that when a crime was reported, the mere mention of the proximity of a street lantern in the report increased the chances of a conviction exponentially. So it is not that the lanterns actually increased visibility or enabled a reduction of crime, rather they put into action a new legal framework that used the idea of this technology as a way to maximize prosecution.

I find it useful to use old technologies to think about new ones, and in this sense, I think there is a parallel to be made between debates around the effectiveness of street lights and those around the effectiveness of police dashboard or chest cameras in monitoring police abuses.

In many of your works, the relationship between light and darkness is a central aspect, how so? And how does this relate to Beirut?

I think I mentioned some of the ways above. How artificial light ends up sculpting public space, and private space. How the administration of light and darkness regiments the manner in which we move back and forth between the two realms.

Increasingly I am also thinking about how light sculpts spaces of leisure and entertainment, how it distributes our attention towards what is to be looked at and what is peripheral, how it orients our bodies towards a stage, a screen etc.

I come from a place where daily power cuts are one of the manifold representations of a corrupt political class, but it also regiments our lives down to its most intimate details. I think about these various styles of neoliberal control—on the one hand the smart cities, eco-friendly, self organizing, frictionless and so on…and on the other a place like Lebanon, also a no holds barred neoliberal regime, but that is run on dysfunction, shortage, outage, friction, chaos etc. I am trying to find visual languages that can account for these different approaches to a same ideological framework.