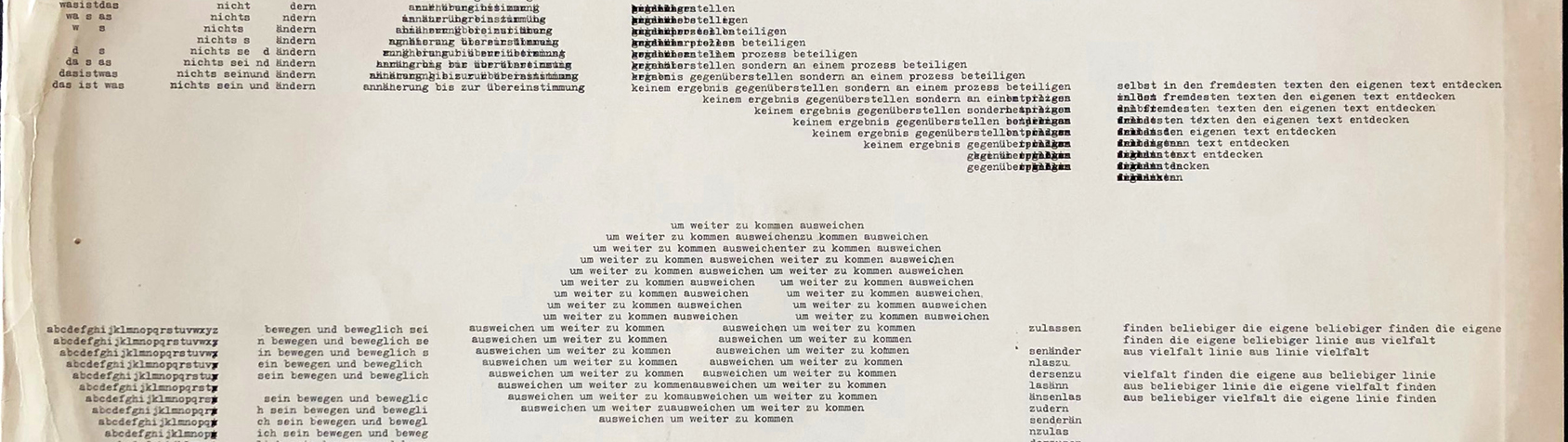

Exercise of Freedom

The history of 20th Century Phonetic and Sound Poetry in a journey from voices of the past to the present

The exhibition The Liberated Voice – Sound Poetry curated by Eric Mangion and Patrizio Peterlini in co-production with Bonotto Fondation offers, without nostalgia, a journey from voices of the past to the present. It plunges us directly and deeply into these artists who still use words and sounds as an exercise in freedom. Poetry continues to place mankind at the heart of life and art. How to remain human when the world is becoming increasingly multiple? How to affirm your singularity?

In the 20th century, Phonetic and then Sound Poetry has always represented an act of emancipation. At the risk of sometimes abandoning semantics, the avant-gardes have made it the spearhead of their struggle against systems, beliefs and dogmas. What remains of these heroic struggles today? Myths and legends. However, times have changed, so have the fighters. Utopias don’t look the same anymore. New technologies have now invaded the space of language, for better or for worse. For the worse, by imposing a digital rationalization of words and sounds. Shakespeare’s English became Wall Street’s. For the better by giving language infinite sources and tools. Since the 1950s, technological advances have allowed phonetic poetry to become sound. But one gets lost between the use of these tools as simple vectors, the absence of poetry behind technical processes or, even worse, the fascination in their (cultural) power. One also gets lost because orality has made a great return to art in recent years, sometimes in the confusion and inappropriate use of words. But sound poetry evolves with its time.

La voix libérée – Poésie sonore exhibition (Liberated Voice – Sound Poetry) offers a path, free of nostalgia, between the voices of the past and those of the present. It immerses us in a direct and absorbing way among artists who still use words and sounds as an exercise of freedom. Poetry still allows us to put man at the centre of life and art. How to stay human while the world multiplies? How to assert one’s own singularity? The result of more than a year’s research, the exhibition is designed as a device that crosses sound poetry, in a non-exhaustive way, from the end of the Second World War up to contemporary developments. Voluntarily trans-historical and international in order to affirm the continuity of practices and experiments, this device is conceived as a listening point, a transmitter producing a frequency that spreads outside the walls of the Palais de Tokyo.

Sound poetry, in the strictest sense of the word, was established at the end of the 1950s, from the coming together of phonetic experiments and magnetophonic technologies. Particularly in Paris, where artists belonging to the Lettrist movement were active, such as Altagor (creator of Métapoésie in 1947 and the following year, his Discours Absolu, which ended in 1960) and Arthur Petronio (an artist already active in the period between the two wars, who in 1953 created Verbophonie: a polyphonic symphony influenced by the poetic “instrumentalist”, based on the intrinsic musicality of the vowels and consonants theorized in 1899 by René Ghil in his Méthode Evolutive instrumentiste d’une poésie rationnelle, and on the experiments of Jean-Louis Brau, companion of Guy Debord and Gil J. Wolman in the International Lettrist).

By using tape recording techniques, poets can finally identify new expressive spaces. With audio editing, the techniques of collage and décollage are spread in analogy with what was already happening in the visual arts. This led to the cut-up of Brion Gysin in 1959 (an idea later taken up by William Burroughs) and the wide range of technical tests of a whole host of new poets, voice, speech, sound and gesture artists, firstly Henri Chopin, who since 1957 has been using echoes, reverberations and speed variators for the treatment of sound matter, and Bernard Heidsieck, who, since 1959, has channelled his poèmes-partitions into the multipista.

“With electronic searches,” writes Henri Chopin, “the voice has become concrete at last.” In a 1961 article in OU Cinquième Saison, the magazine published by Henri Chopin, Petronius wrote: “The plasticity of words in their acoustic representation, the imperative approach of their timbre reality, their vibratory character, their onomatopoeic roots, their morphology, their semantics, for verb poets constitute the indispensable materials for poem construction, for its architecture.” The urge to create “a poetic composition beyond writing, directly into the microphone” emerged with François Dufrêne and his cry rhyme (a synthesis between the cry: “an inarticulate sound that does not necessarily imply a bursting of the voice” and the rhythm “that does not necessarily imply cadences”). Starting from this assumption, authors such as Henri Chopin, Brion Gysin and Bernard Heidsieck have all investigated new possibilities for the analysis of sounds (vocal or recorded in different contexts), their editing, amplification, superimposition, reverberation and speed variations, arriving at a wider and more multiform manner of composition, in contrast to previous methods of live acting.

Thanks to his creative activity and editorial activity (he founded and directed the magazine OU Cinquième Saison), as well as his activity as a historian (with the publication in 1979 of Poésie Sonore Internationale), Henri Chopin has played a pivotal role in the field of sound poetry. “Chopin,” writes Sten Hansen, “was not the first to use the microphone as an instrument of the poet, but he was certainly the first to realise the fundamental potential and the first to clarify the theoretical level.” From the first works (Pêche de nuit, Espace et Gestes, Sol-Air) in which words remain the starting point of the poetic process, thanks to the technique of over-recording, a new dimension is attained in which the voice-sound gives way to a “pure audible unity,” essentially composed of body sounds (Mes Bronches, Le Bruit du Sang, etc.).

Bernard Heidsieck, another important figure in Sound Poetry, began his experimentation in this field around 1955. From 1959 he began to record his “poèmes-partition,” also called “poésie-action” with a microphone, followed in 1966 by his “biopsies” and in 1969 by his “passepartout.” In his work incorporating the sound landscape of everyday life, such as noises recorded in school playgrounds, shouts garnered from a street demonstration, accompanying them with “an amazing voice… a language of ellipses, …of breaks, exclamations, cuts” with which he interprets his texts, like Vaduz (1975), or Le Carrefour de la Chaussée d’Antin (1972) or even Canal Street (1976). Other authors who have made important contributions in the field of Sound Poetry are: the Germans Franz Mon and Carlfriedrich Claus, the Austrian Gerhard Rühm, the Englishman Bob Cobbing, the Flemish Paul De Vree and the Bohemian Ladislav Novak. A special iterative treatment of the text produces polyrhythmic sound layers in the works of the Swedes Sten Hanson, Bengt Emil Johnson, poets from the Fylkingen Centre in Stockholm, as well as the American Charles Amirkhanian. The French Ilse and Pierre Garnier, authors of the “souffle manifeste,” Julien Blaine, the Americans John Giorno, Richard Kostelanetz and Larry Wendt, the Canadian group of Four Horsemen with Steve McCaffery, Paul Dutton, Raphael Barreto-Rivera and B, are also to be remembered for the quality of their work, along with B. P. Nichol, the Spaniard Bartolomé Ferrando, the Russian Valeri Scherstjanoi, the Hungarians Katalin Ladik and Endre Szkàrosi and the Swiss Vincent Barras.

In Italy the most active poet in this field of research was definitely Arrigo Lora Totino: inventor of “liquid poetry” and “gymnastics,” who composed his first sound poems in 1964 (Phonèmes recorded in Turin between 1965 and 1966). Later, in 1968, he published Il Liquimofono, a device that generates Liquid Music and Liquid Poetry, inflections plunged into the hydromegaphone. In 1978, he published Futura Poesia Sonora (Future Sound Poetry) a historical-critical anthology of sound poetry composed of 7 records. Honourable mention also goes to: Adriano Spatola, to whom we owe Baobab (1979), the first Italian audio-journalist of sound poetry; Mimmo Rotella, author of the Manifesto of Epistalism, Enzo Minarelli, theorist of Polipoetry, Giovanni Fontana, theorist of Pretextual Poetry and Epigenetic Poetry, and Patrizia Vicinelli, Luigi Pasotelli, Maurizio Nannucci, Tomaso Binga, Giuliano Zosi, Sarenco, Massimo Mori, Gian Paolo Roffi, Sergio Cena and Gian Pio Torricelli. All these experiences have left a legacy that has been collected and developed by successive generations. This legacy, even if it sometimes seems heavy because desires for experimental freedom and feelings of transgression, so fertile in the 50s and 60s, appear obsolete, giving rise to spectacular excesses and a certain theoretical weakness, sometimes affirmed as a need for emancipation from the system of art and literature, yet they remain fundamental to contemporary sound poetry, alive and practiced by many young poets in the world.

Some authors, such as Kinga Toth (Hungary), continue the investigation into the expressive possibilities of the phonatory apparatus as initiated by Henri Chopin. Others, like Tomomi Adachi (Japan), investigate the possibilities offered by new technologies by developing electronic devices that interact with the voice, creating surprising sound modulations. Still others are creating a form of poetry that combines historical sound poetry with the most recent digital poetry, creating digital-sound hybridisations that find their specificity in the massive use of new digital technologies. This is the case, for example, with Joerg Piringer or the recent work of Caroline Bergvall. A vitality of research developing throughout the continent, from Joerg Piringer’s Austria to Amanda Stewart’s Australia, from Zuzana Husárová’s Slovakia to Kgafela or Magogodi’s Zambia, from Felipe Cussen’s Chile to Ian Hatcher’s U.S.A.

The exhibition, through the work of contemporary poets and continuous comparison with the works of their predecessors, aims to investigate what power Sound Poetry still has today. What body did you request yesterday? And what body does it mobilize today? In the succession of individual and collective liberations, what is clear in word, voice, gesture, gender and sex, what does it shape in space and in the scene, in sounds and images? What are the uses and the audience’s expectations? This exhibition therefore proposes a reflection on some established aesthetic forms, their content and meaning in relation to today’s culture, in mass media and in this society of communications.