Wishing-thinking

When magic is indeed all around, or “Who Wants to Live in a World Without Magic?”

Curated by Katayoun Arian,Who Wants to Live in a World Without Magic? is currently on view at Tent, Rotterdam. Across cultures and histories, consciousness-altering practices by shamans, mystics, and other healers, have had a longstanding relationship with art making, and with sound and music in particular. At this time of radical planetary disorientation, imagining restorative processes by way of cosmic consciousness can assist us in creating fertile grounds towards a path of mourning and healing rooted in a collective capacity. The works in the exhibition and hybrid events program invite us to consider multiple, re-enchanted ways to envision our interdependencies in our more-than-human material and metaphysical realms. Here a review and walk-through by Marianna Maruyama.

I happened to visit the exhibition Who Wants to Live in a World Without Magic? on Black Friday, the most commercially oriented day of the year in the global north. On this (holi-)day, consumers are courted and tricked by the cleverest means to indulge in empty fantasies, while already-abstract currency is transformed into electronic goods, telematic devices, perfumed mists and make-up. It makes sense on this day especially to think about magic and its many wordly manifestations. Magic is indeed all around, its power is not relegated to an elite group of initiates, and it is not in the realm of divinity. In its most profane expression, magic happens in the transformation of labour to cash currency, of desire to exploitation, and in the mass mobilization of demonstrators, mobs and militaries.

The exhibition currently on view at TENT Rotterdam curated by Katayoun Arian strives to share different possibilities of magic, and more specifically, other explorations of magical worldviews. Unlike the mountainous overflow of consumer goods on sale this week, such subtle viewpoints cannot be possessed within minutes. Furthermore, they do not necessarily spark desire, which is also their power.

Encountering magical worldviews asks us to work with a different vocabulary, and to use other languages, an endeavor which, while not impossible, takes time. In this review, I want to consider the reasons Arian had for putting these works together, the wishing-thinking behind the artists’ works, and the deeper motivations for trying to introduce different logics into an institutional space that perhaps unavoidably carries hard-to-undo notions of art, culture, and value.

Discourse analysis begs for the articulation and clarification of terms at hand, and that is where Pernilla Ellens’ critique of the exhibition in MetropolisM wants to go. The author wanted to see the exhibition holistically, as a unified and coherent whole but was left a little unsatisfied. They felt the terminology used to describe the works was ambiguous and some terms were used interchangeably. Had this exhibition been a dissertation or claimed to have taken a singular stance about defining magic, it would have been a useful critique. But recall, the title of this exhibition is a question. Even if it’s a leading question, it’s not a statement.

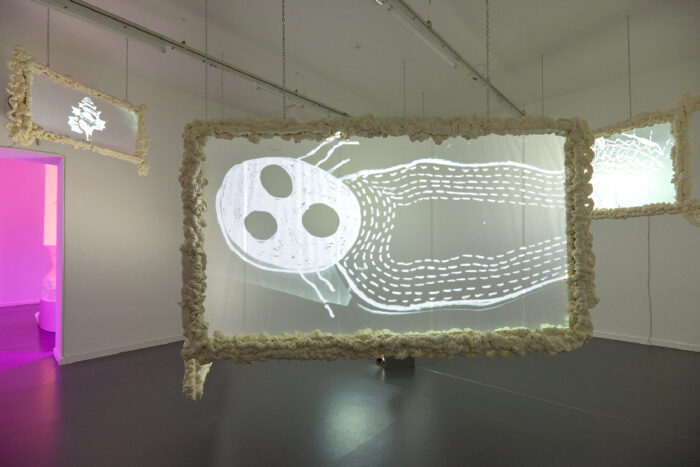

In an attempt to reduce simplistic perspectives or at least lower their frequency, the works here try to ask “what worlds to world”, placing the observer in an unstable arena between the oppositional poles of so-called rational thought and different ways of being-thinking-feeling in the world. They do this through lived explorations of mental health, image making, casual dialogue, and material experimentation and ritual processes within the making itself.

Through these explorations, I think, they wish-to-become.

I am still not sure if these works bring me with them, or let me come closer, but I sense that some of them wish to do so, and I wonder how close the cousins of wishing-thinking and magical-thinking are?

Magic, in its recent framing in artistic contexts appears at first as a safe space of unlimited potential: a necessary space that could have only been cleared in an unstable and desperate time. In art and sound practices of the past few years, magic and the occult have taken a central role either as a kind of emancipatory movement from the oppression of extractivist logics or as an escape from hegemonic narratives. In the recently published essay Strategischer Obskurantismus, philosopher Christoph Haffter takes a critical position around the admission of spiritual rituals in contemporary art and music that touches on some of my questions about bringing esoteric practices into institutional spaces. “As soon as the rituals are considered art,” he writes, “they are rituals that no one believes in.” It is not my place to question the authenticity of an artist’s beliefs, but I cannot be expected to believe in them myself. This doubt returns me to a position of kind of skeptical distance, precisely the thing I sense I was expected to reject. And yet, I find this position fascinating because it oscillates between poles: on the one side a space, not to say a necessarily safe one—of magical thinking and potential, of re-animation and transformation, and on the other, a space of de-ritualized inanimate objects and statements—an already finished space.

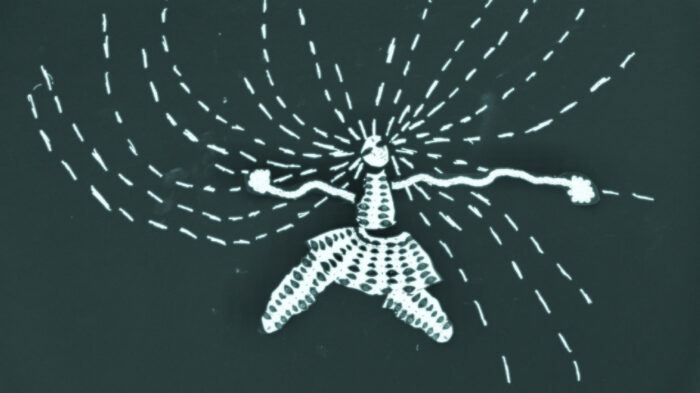

I enjoy this conflict within the exhibition concept. I also appreciate the messiness of some of the works in the exhibition, their refusal to conform to a singular definition of magic, their diversity of material choices, and their origin stories. There is an attempt, for example in Shertise Solano’s self-searching work With as Far as Eye Can See, to deal with repressed trauma through shadow play and animation. The visitor becomes a part of the work as they pass through or linger. We all bear shadows, it seems to remind us. This work doesn’t bring me close to my own traumas or mourning, but why should it? It does not claim to be therapeutic but rather it shows one person’s way of dealing with repressed trauma. In her curatorial statement, Arian proposes that the artists’ works highlight the power of the critical imagination. Can we give ourselves permission to visit these sites and scenarios imagined by others, even if perhaps we do so unschooled, or as an outsider?

Noticing how my own body could take different shapes as I walked through the space was a small gesture of transformation—stepping inside one of Narges Mohammadi’s larger-than-life sized sculptures made of sand, silt and clay, Attempt for Refuge, or climbing into the chaotic tent constructed by Natalia Sorzano in the installation Contesting Madness to lie down and watch a quartet of multi-layered videos dealing with mental health, and set within the city of Rotterdam. Tja Ling Hu’s series of fine-lined drawings, the most conventionally visual works in the exhibition, brought me a different awareness of my own body specifically in the context of classical meditation poses. The drawing Shavasana, as one example, let me better understand the restorative nature of a pose I have done many times but have not pictured.

Anna Hoetjes’ clay tablets The Dust of Venus and vibrantly glazed tiles Aphrodite Terra are intelligently built around the context of her chosen materials and production techniques. The clay tables are carefully crafted from the same chemical composition of the planet Venus, while the tiles are grounded within the specific social and historical context of scientific visual analysis.

Narges Mohammadi’s work is also built out of planetary materials, in this case, our planet Earth. Among their qualities, the prominence of craft and care speak resolutely in these inviting sculptural pieces. A few other artists in this exhibition favored the use of synthetic materials, something that initially surprised me probably because of some misguided notions about works dealing with magical processes being more sacred and rare. I had expected to see even more of the materials of the earth—minerals, metals, pigments, and biological materials. These works reminded me that we live in 2021, and our materials are plastics, and I was glad to have the chance to dismantle my preconceptions. Why should magical worldviews need to be constructed with special materials, when synthetic trash is such a big part of the global economy and ecology now? Hot glue, chicken wire, polyurethane foam, vinyl stickers, polyester, plastic, all these provisional materials are bound for the bin but in fact will last longer than our fragile aqueous bodies.

Mehraneh Atashi’s installation, Seeding My Feet in the Chant of Bells offers an analogy of growth and potential. Apparently, not all seeds sprout, both in the actual material artwork and metaphorically. Anyone who has patiently observed seeds sprouting can attest to the fact that not every seed comes forth. Some are simply bound to remain dormant, dead or dry. This is not a criticism (ie. ‘Atashi, why doesn’t your garden grow?’), but an observation on the nature of potential. It can also be read as a reflection on institutional care, bringing up the question of who will water the plants throughout the exhibition. Biological materials are not always willing participants in artworks—and that includes us.

Going back to the idea of wishing-thinking and magic, it is not my place to doubt whether or not the participating artists actually conduct the rituals or magical processes they seem to be interested in, or how deeply they believe in the ideas they put forth. It is not the duty of an artist to be honest. Nevertheless I find myself asking what happens when rituals and magical worldviews are invited into an institutional exhibition space, whether they are truly inviting, and most importantly what and whom do they invite? Instead of trying to see the exhibition as the definitive expression of an overarching concept or as a collection of individual works, which each have their own distinct qualities, it might be most meaningful to attend to all of the questions the works have surfaced: What power relations do they threaten? What new worlds will come forth? When magic is truly believed in, it can be powerful, awe-inducing, and scary. On that note, just recall how horrifying Black Friday is.

Note: In this review I was not able to consider the work CACHE/SPIRIT by electronic music duo Animistic Beliefs (Marvin Lalihatu and Linh Luu) and multimedia artist Jeisson Drenth because that part of the exhibition ended prior to my visit. Furthermore, I regretfully did not participate in the online and offline hybrid events program which included intimate gatherings and listening sessions, and included the work of participating artists (amongst others), the Mourning School and Raoni Muzho Saleh.