Whistling Choir

A conversation with Aliaskar Abarkas

Imagine for a moment to whistle attuned to other mouths, would you follow or take the initiative to lead? Is it whistling like flocking, or is there more than mere automatism? When do you usually do it? Aliaskar Abarkas transforms the impromptu intimate habit of whistling into a collective pedagogical practice of interplay between individuals. Through the study of the volumes and collective vocal exercises, the artist and the workshop participants worked together to develop an imaginary language, thus materializing it into a musical composition.

The workshop The Community Whistling Choir took place in June at the Biblioteca Casanatense in Rome as part of If Body’s program, and focused on the library’s unexplored collection of Persian and Arabic manuscripts, dating back as early as the sixteenth century. In September, the result of the workshop will be presented in the form of a sound installation within the framework of Short Theatre.

If Body is a public visual and performing arts program that focuses on the body as an artistic language and learning methodology based on experience and participation. Conceived and curated by Sara Alberani, Marta Federici, and Chiara Siravo (LOCALES), this year’s edition is titled Living Fragments. Through seven events, it presents new performances, talks, workshops and exhibitions that explore the cultural, social, and political meanings associated with the body and corporeality. This edition features interventions by Aliaskar Abarkas, Soukaina Abrour, Adelita Husni Bey, Noor Abed & Lara Khaldi (School of Intrusions), Emily Jacir & Michael Rakowitz.

Giulia Crispiani: How did you learn to whistle? As personal as it gets! And how did it become such a central part of your practice?

Aliaskar Abarkas: Immediately as soon as you asked that, I had a flashback of me as a child, always whistling. Everybody was telling me off because it’s considered bad behavior, right?

What kind of whistle?

[Giulia whistling]

Actually, I never could do that. More like this:

[Aliaskar whistling]

Ok, so a musical whistle.

I remember exactly how much I was told off by everybody when I was a child. This created a negative association with whistling and I almost had to censor myself. I wasn’t happy about that. I love whistling.

That’s difficult to do.

Yeah. At home, I whistle all the time. But since starting the whistling choir project, I self-censor because I associate whistling with work. Sometimes it doesn’t have that joyful lightness to it anymore: whenever I hear someone whistling, I immediately start thinking about my work. Before the choir, I was more spontaneous and skilled.

When I moved to London from Iran, my experience of immigration and speaking a language different from my mother tongue made me reflect deeply on language itself. For example, I was influenced by reading Deleuze and Guattari’s Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature and the classic conceptual art publication Art and Language. I paid close attention to the use of language in modern and contemporary art practices. Later, I also became interested in its musical aspects, such as accents and intonation.

Recently, I was going through some folders containing my poems and short texts and found a paragraph where I described a scene I couldn’t put into words. Instead, I wrote: “Therefore I started whistling, and I don’t know where this is resonating or who might hear it, but I continued.” This was in 2019, and I started the whistling project in 2022. It is fascinating to see how ideas develop in our unconscious mind. So my brain processed the ideas, and eventually, I materialized it, so the starting point dates back long before it became “art.”

Also how coherent you are with yourself.

I often use the term “coherence” when discussing my work. I have long envisioned designing a mechanism where my work could circulate and take on contingent, unexpected forms while remaining coherent in its narrative. This is part of my methodology. I also enjoy working with people and the dynamics involved in coming together as a group. It’s part of my personality and the practice of everyday life. In contemporary art, many terms are misused or manipulated, such as community, collaboration, and care. I am careful about how and when I use them.

Also, language can be violent on many levels and very dividing when you work with others. In politics, for example. Much of the time, it is miscommunication that can cause division. I was interested in working with a language that connects rather than miscommunicates, and I think music is capable of that. I wanted to create a musical environment geared towards togetherness. I am not a musician, my background is in visual cultures and politics, and my practice is mainly shaped in the context of alternative and collective learning programs.

Towards the end of 2022, during the Women, Life, Freedom protests in Iran, I participated in a fundraising event in support of Iranian women. I invited the audience in London to whistle together the tunes of the revolution that were being sung at the time. I wanted to create a moment everyone could feel, where everyone could unite and participate. The response to the workshop moved me deeply. I had never seen such a strong emotional response to my work. Some people were crying. Someone told me they had never felt included in art before. In a strange way, it felt like the first time I made art.

Which is quite interesting actually, because we are seeing this from the point of view of artmaking but then somebody reacts to this feeling that they belong to an artistic process, right? But then there is also the place where this tune comes from. This collective experience of being in the revolution and the emotional load that comes with that, the political charge which is not outspoken, but it’s still embedded in these melodies. I imagine, I don’t know. I mean, I find this kind of process really interesting: leaving words out and then creating collective moments that are still informed by something that is loaded with meaning, so to say. Because the melodies that you take, they have words.

In this first phase, we drew from revolutionary melodies. Later, I took the workshop into different places and contexts. This was a pivotal moment in my practice, where I had a revelation and felt that everything I had been doing over the past ten years came together. I felt very confident, like I knew what I was doing. As an art student, I explored many mediums, letting my curiosity guide me. But there was a moment when I realized my mission and had a clear vision for it.

Yet my work remains experimental. I like to take risks. For example, performances are always different. Sometimes they work well, and other times they serve as valuable experiments, even if they don’t meet the conventional expectations of a finished work. I never thought my work was supposed to be finished. It has slowly become more refined, even if it captures only a fragment. It is all part of an ongoing process.

Yes and almost automatic. Earlier I was thinking we whistle while doing something else. It’s something that comes out of you. So I’m also interested in how, methodologically speaking, you bring it into the collective space. How do people start whistling with you?

During my time as an associate artist at Open School East in Margate, a year-long alternative education program, we were expected to put together a final exhibition. I decided that I didn’t want to participate in the group show in the main building; I needed a different space. I spoke to the Cliftonville Community Centre in Margate about hosting weekly gathering sessions. It was a beautiful space with amazing acoustics. I invited members of their community and my peers to take part in a series of whistling exercises, listening sessions, and collective music-making, leading to a performance for the Refugee Week festival.

For the first time, I began a conversation with an external institution to see if they would allow me to enter their space and collaborate. This has now become very central to the conceptual framework of my practice—collaborating with individuals as well as institutions. I aim to mediate not only between individuals but also between institutional bodies that often don’t work together.

When I host an event, I am very aware of how to keep it engaging and entertaining. I get bored easily, so I knew it had to be fun and engaging. It was never just a whistling workshop; it was about creating a moment of coming together and being creative together. I also aimed to decentralize my role as an artist and proliferate perspectives among those who take part in the process. By doing this, my work takes unexpected forms and develops organically. Although I closely guide and mentor the process, I hold the space by welcoming everyone to take part.

So what remains of these experiences? What does the material become after? How do you keep it with you? Does it grow as an archive or does it go on the radio for example?

I might regret this decision, but I was intentionally thinking less about documentation and more about the moment of presence and the ephemeral quality of the experience. I encourage participants to document the process and experiment with the aftermath of the collected materials, which has led to radio shows, soundscapes, and even paintings. The question of documentation interests me. I don’t think taking pictures or recording the materials is the best way to document my project because that doesn’t really do the job, you know? I find it flattening, and I don’t want that. I came to understand that I want to approach it differently: I wanted to make it more imaginative and mystical.

For instance, lately, I have been thinking about religious paintings in churches and the performativity they evoke—the composition, the groups of people in different poses. My paintings are inspired by these types of iconography, recomposing the photos of the figures from the rehearsals and fabulating the atmosphere, hoping the paintings can also carry a sarcastic hint. There is humor in them, I think. I also wanted to create a system where the materials collected from the processes could later circulate and expand and be re-composed.

But indeed you are also interested in stretching the whistling into a composition. Then you take the, let’s say, the paratext/apparatus of the composition.

Defining what musical composition is can be very tricky. However, I am excited to explore different traditions in compositional temporality. We whistled revolutionary tunes, improvised to make music, and now I have commissioned multiple composers from very different backgrounds and musical textures to compose music for collective whistling.

I ask composers to join the workshops and facilitate the group to understand the project and the specific challenges of writing music for whistling. It can be very tricky. I try not to give them clear instructions, allowing them to be inspired and respond to the idea based on their own practices. However, I do ask them to consider that not everyone can whistle skillfully and to be mindful of creating an inclusive space that welcomes those who have not previously participated in the sessions. Over time, I have also realized that whistling is about breathing—inhaling and exhaling while making a noise. My question is how to create a structure loose enough to contain improvised moments, while remaining coherent.

So for If Body 2024 you will engage with such a rich archive that is Biblioteca Casanatense, so speaking of references, here you are beginning from one. What have you worked on? How are you engaging with the location?

LOCALES invited me to work with them for their 2024 program, which had the concept of the body at its center and they were interested in the whistling project. I was at the stage when I had to ask myself if the project had exhausted itself or if I wanted to commit to the vision I have—to craft the scale I have in mind.

I am interested in making the project monumental in some way. I believe a work of art becomes monumental when it is experienced collectively rather than individually. I would like to create a contemporary myth, and this involves scale—whether 10 people whistle or 10 million, the experience will be very different. So I am thinking of scale as a medium.

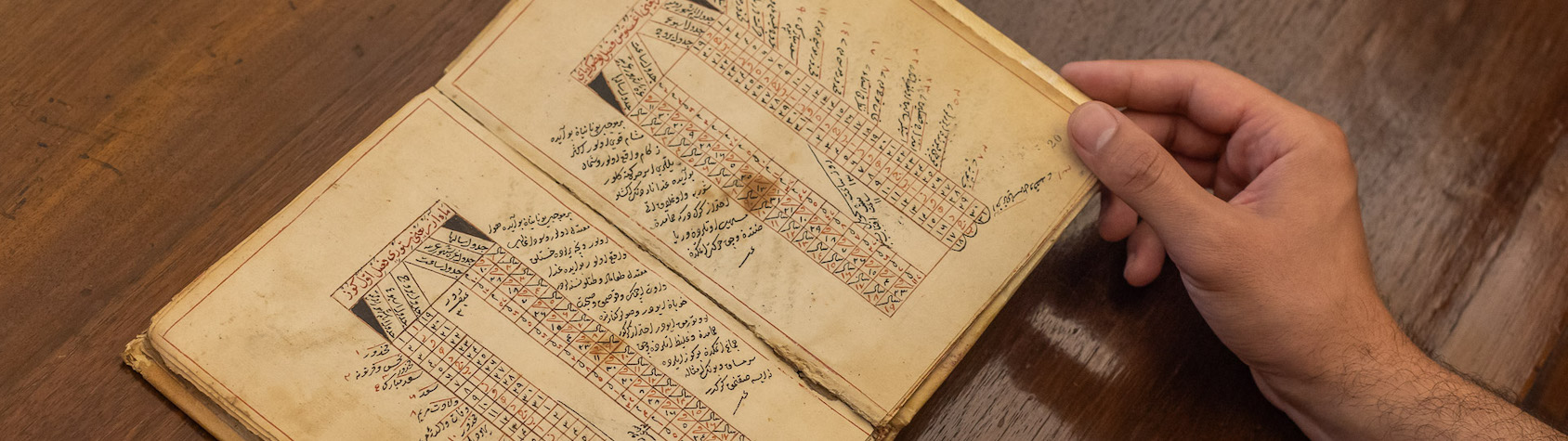

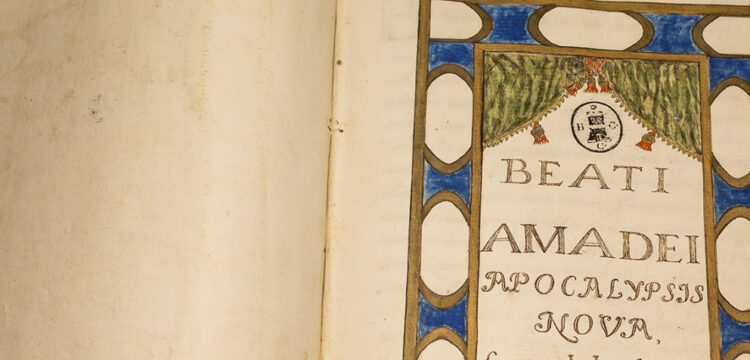

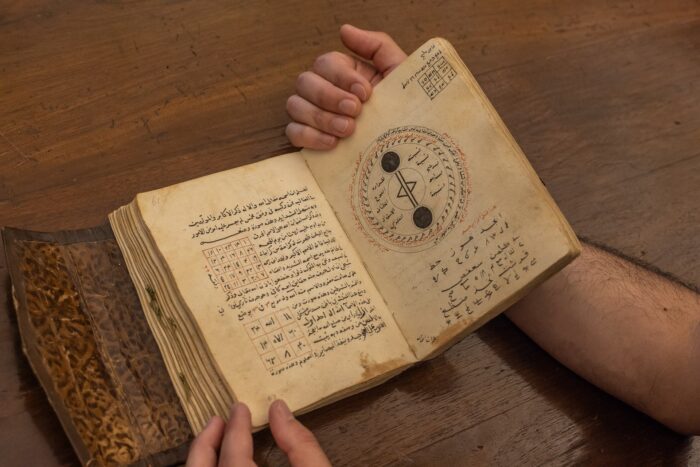

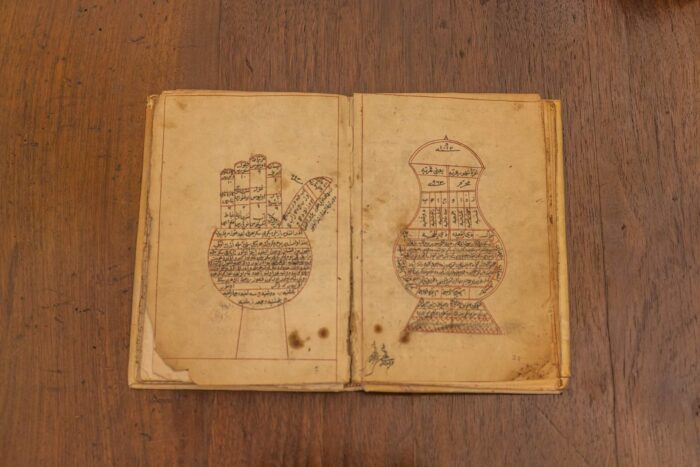

Moreover, each opportunity, like the one with LOCALES, is a great chance to experiment with different ways of working and to be inspired by the context, space, and the people I collaborate with, including the curators. With LOCALES, we visited the Biblioteca Casanatense, one of the oldest libraries in Italy, filled with forbidden books. As soon as I entered, I was fascinated by the fifteenth and sixteenth-century drawings in the vitrines. We came across a Persian and Arabic manuscript with numerical occult codes, blending witchcraft and geometry. I had already been interested in numerical languages and had some understanding of them. The manuscripts have a supernatural quality, much like whistling does, which is also associated with the supernatural in many cultures. In Iran, we say that whistling in a closed space summons the spirits, which is one reason why it’s discouraged.

I saw a narrative in these books from which to build the workshop. I was interested in revisiting these materials to interpret them differently and create a new reading or entry point. So I decided to approach the content of the manuscripts as a way of introducing our own coded language and then translate it into a sonic one, quite abstractly.

Understanding these materials requires familiarity with the esoteric linguistic systems used by specific communities, involving constant ciphering and deciphering. It’s a shared code among a group of people. I wanted to use this structure almost like a play to construct an internal language and find its musical equivalent. Engaging with the space and the architecture of the library is a crucial aspect of each workshop, adding another layer to the experience. I also looked into the medieval musical scores in the Casanatense collection to see if they could become the starting point for a melody.

What will the material become after the workshop? How will it circulate?

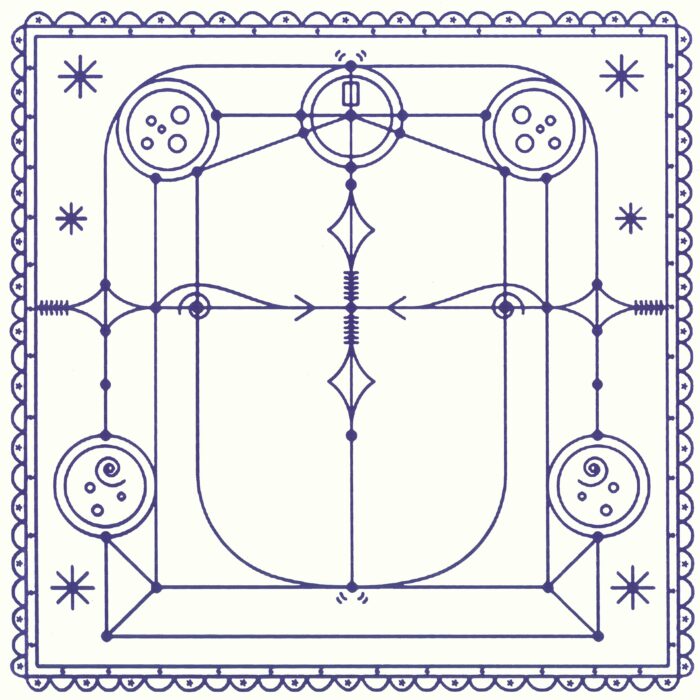

During the first day of the workshop, we vocalized the spells from the manuscript. The geometry of the spell informed the placement of our bodies in space. On the second day, I employed the same method to create an exercise in scoring our music visually, together with the workshop participants. I then worked on the drawing, and it has been produced as a screen print. The recording will be re-worked to function as a sound installation at Short Theatre in September 2024.

How are you responding to the hint of fragmentation?

Fragmentation is a term I use often. A splinter of something is not necessarily meant to be incomplete but rather it can follow a structure capable of carrying enough essence to stand alone without being elaborated on. Also, they carry different meanings in relation to other surrounding fragments, and the sequence of individuated fragments can develop into drastically different narratives.

I think of my practice as a mechanism that holds various fragments together and changes the relationality between each of them to bring a fresh perspective. My writing is quite fragmentary, just like each workshop or performance is. But they also complement each other and allow different stories to emerge.

In relation to this, I should also mention the practice of marginalia, which was present in the manuscripts. Marginalia refers to the text written in the margins of a book by the same author or other scholars. Some of these books had multiple layers of marginalia: one from the author explaining what is in the book and another from researchers adding notes over time. It’s like another fragment and another interpretation over time, all encapsulated within the body of a book.

I’m thinking about fragmentation also in relation to whistling, because whistling is not like a composition. When you whistle, you switch from melody to melody. Or?

It can be a very fragmentary musical practice in everyday life. Perhaps it depends on how we think about it. I think about art as a discourse that allows you to scatter and fragment things, rearrange them differently by making new connections between elements that are not necessarily related to each other. I think that, for example, a project like LOCALES does this on a different level, by sharing different narratives and their curatorial reading of the term with artists, but also their approach, all these fragmented locations, different public spaces…