Water Infrastructures

Within the colonial continuum: a conversation between Adelita Husni Bey and Shehrazade Mahassini

The following conversation between Italian-Libyan artist Adelita Husni Bey and scholar and architect Shehrazade Mahassini (Royal College of Art, London) unfolds around the concept of infrastructure, in order to explore the management of water resources within colonial processes, and the current climate crisis in the Libyan context.

This exchange followed A collection in turmoil III – Water Infrastructures within the Colonial Continuum, a conversation between Husni Bey, Mahassini, and Giulia Beatrice (Biblioteca Hertziana, Rome), hosted on June 27th at the Museo delle Civiltà in Rome as part of the If Body 2024 program. The conversation anticipated the workshop A Collection in Turmoil III – Vulnerable Infrastructures, led by Husni Bey at the museum later in September. This project was commissioned and curated by LOCALES as a progressive and shared analysis of the collections of the former Colonial Museum of Rome.

This year’s appointment resulted in the video installation Like a Flood (2025), which was presented at the Sharjah Biennial in 2025, co-produced by the Biennial and the Museum.

If Body is a public visual and performing arts program that focuses on the body as an artistic language and learning methodology based on experience and participation. Conceived and curated by Sara Alberani, Marta Federici, and Chiara Siravo (LOCALES), this year’s edition is titled Living Fragments. Through seven events, it presents new performances, talks, workshops and exhibitions that explore the cultural, social, and political meanings associated with the body and corporeality. This edition featured interventions by Aliaskar Abarkas, Soukaina Abrour, Adelita Husni Bey, Noor Abed & Lara Khaldi (School of Intrusions), Emily Jacir & Michael Rakowitz.

Adelita Husni Bey: It’s such a pleasure to be in conversation with you again. We’ve now been co-inhabiting the same research space for almost a year, and I’m really happy to be speaking with you today. This discussion stems from the workshop organized by LOCALES at Museo delle Civiltà in Rome last September. As in past years, I engaged researchers, students, and museum staff in thinking through historical questions tied to institutions and infrastructures—using Augusto Boal’s Theater of the Oppressed to explore knowledge production beyond oral and written traditions, emphasizing embodiment.

I’d like to start by reflecting on the objects we encountered during our visit in June, particularly those related to water infrastructure, the core of our shared research. I was especially struck by a wooden water jug and another made from skin or an organ. These objects, which I later brought into the workshop, made visible historical water infrastructures—now largely hidden—such as pipes and domestic water systems. They revealed a past where water transport in Libya was deeply tied to local resources and human movement, especially in pre-colonial, semi-nomadic contexts.

Shehrazade Mahassini: It’s a pleasure for me, too. The last year was indeed enriching and incredibly grounding—researching water extraction in the Libyan desert and the Jabal Al Akhdar roots you in soil and subsoil, it is an offering from encountered ecological cosmologies, and at the same time it is this constantly strident wake-up call: the collapse and despoliation of ecosystems.

I think this collaboration opened the Pandora’s box, which we had not expected to open. The Italian archives, the Libyan ground and living archives encountered during the year not only showed the violence and power of the archives as a site but also the silence around water extraction and our complicity as humans, which is excruciating. Especially amidst the climate crisis, criticality around water extraction, management, and distribution is swallowed by techno-fetischists, and capitalism catapulted us into a sort of eco-nihilism. Water is the foundation of any life on earth, and water extraction has this special benign rank within the extractivist list: we need it to sustain life, so we live in a kind of oblivion. It’s interesting how, in the sciences and Western environmentalist discourses, the narrative is centred around the pollution of water bodies resulting from other extractions such as crude oil, minerals, etc. But what about the extractive artillery drilling the lithosphere to pump fresh water to the surface? This as a practice in times of turbocapitalism…

Researching water extraction and its infrastructures goes beyond the physical materialization of the extractive apparatus. I’m trying with this research to dissect the ideological and biopolitical apparatus enabling water extraction and the construction of large-scale infrastructures. Interestingly, it’s exactly the moment when the focus needs to adjust and challenge technoscientific approaches: Who is affected by water extraction? How and can they speak? Here, Spivak reminds us again and again: Can the subaltern speak?

To get to the bones of water infrastructures, I needed to delve into Marina Vishmidt’s infrastructural critique and writings on speculation. To understand infrastructure, rereading her essay was a way for me to further develop a dialectical materialist approach within the built environment. So, infrastructural critique has been, for you and me over the last year, this permanent exercise in praxis, and it is clear we need to look at infrastructure from the perspective of relations and production—and critique as a tool to transcend the performative and institutional.

As she wrote, “(…) this would mean developing a mode for critique that is not only aware of or dedicated to creating awareness of these (infrastructural) conditions of its own enunciation and the classed and racialized conditions of the critical encounter, (…) but a critique that makes cuts and lets in air, a critique that takes it upon itself to find or make the holes through which this infrastructure comes into view. And maybe these holes can be extended to enable a grasping and a torsion to be exercised on those conditions, tugging them into really completely different shapes if necessary, demolishing or abolishing them if not.”

Let’s think about the infrastructures we are surrounded by, dissect them, embody this critique, and start working with and against infrastructure as the inherently evolutionary model: I’m sure many dams, pipelines, and the whole extractive machinery will not only look differently but even not exist anymore. Repurpose to rearrange in a completely other way.

Working at the nexus of architecture, art and research, is my way to unearth counternarratives and go against the grain and the crisis in which the built environment and its aestheticization are: turbocapitalism again.

Today, using environmental studies and research co-opts knowledge production for more commodified water resources and, ultimately, more infrastructures. People believe there is no other way or alternative, especially when we talk about water: water is the very foundation of life and death simultaneously. It’s visceral.

The discourses around adaptability and all well-funded research around the adaptation of infrastructure are striking examples, and you did this amazing research with MIT if I’m right. So, at the end of the day, these infrastructures, these objects, are just one part, which is actually unearthing a huge network of pipelines of goods and resources which are linked directly to the global market: extractive capitalism loves ecological philanthropism.

I really like how your artistic practice is grounded in the workshop; you are using the rehearsal as a method to unearth the historiography of water infrastructures. My work is based on this whole archival material, fieldwork and oral history. There is a great overlap between our practices, and I enjoyed digging the archives in Italy with you. I think that was also the moment we decided to go together to Libya to start doing fieldwork.

Adelita Husni-Bey: There are so many important points you raised. One that stands out is the need to create new epistemologies, which you emphasize in your research. The invisibilization of infrastructure—the fact that we can’t see, touch, or interact with the systems that sustain us—is also rooted in an ideological construct, inevitably connected with modernity. We need narratives that make infrastructure visible because, as Marina Vishmidt said, “broken infrastructures are loquacious.” They speak to us, and we are increasingly living in a world of failing infrastructure— due to age and the growing extremes of climate change.

A key shared point in our research is that by highlighting infrastructure’s vulnerability and material history, we can better understand why it has been hidden from view. Political motives and historical lineages have shaped environments where we are distanced from the structures that sustain us—very different from what we saw, at least superficially, in the ISIAO (Italian Institute for Africa and the Orient) archive. Pre-colonial water infrastructure in Libya, for example, was deeply embedded in everyday life, visible and tangible.

Without romanticizing the pre-modern past, I think it would be valuable to discuss what we found in the archive. Your point about adaptability is crucial—today, climate change is being naturalized rather than understood as a material crisis driven by capitalist economies. Adaptability, in this context, is often used to normalize infrastructural collapse and the disproportionate suffering of vulnerable populations. I’d love to hear your thoughts on this or if any particular images from the archive stood out to you.

Shehrazade Mahassini: All photographs were striking. There was no image which left us indifferent.

All of them were distressing and brutal—we see how the beginning of “environmental studies” at the time was embedded in colonial knowledge production and the very instrument of the Italian colonial project. Ecologies had to be policed, tracked, surveyed, and monitored to be tamed and controlled.

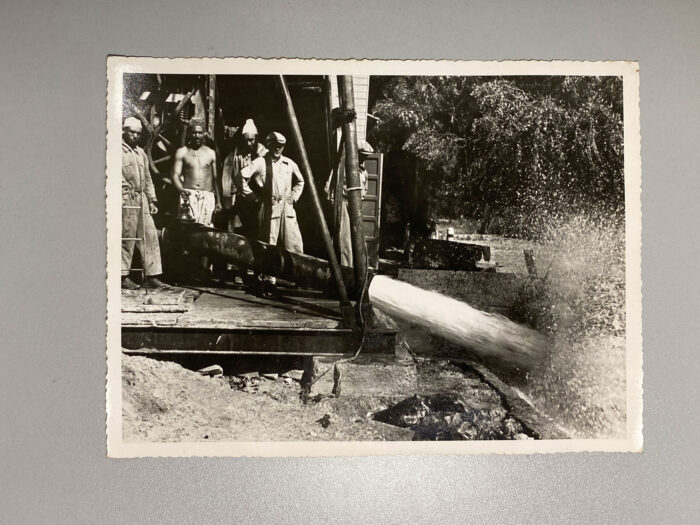

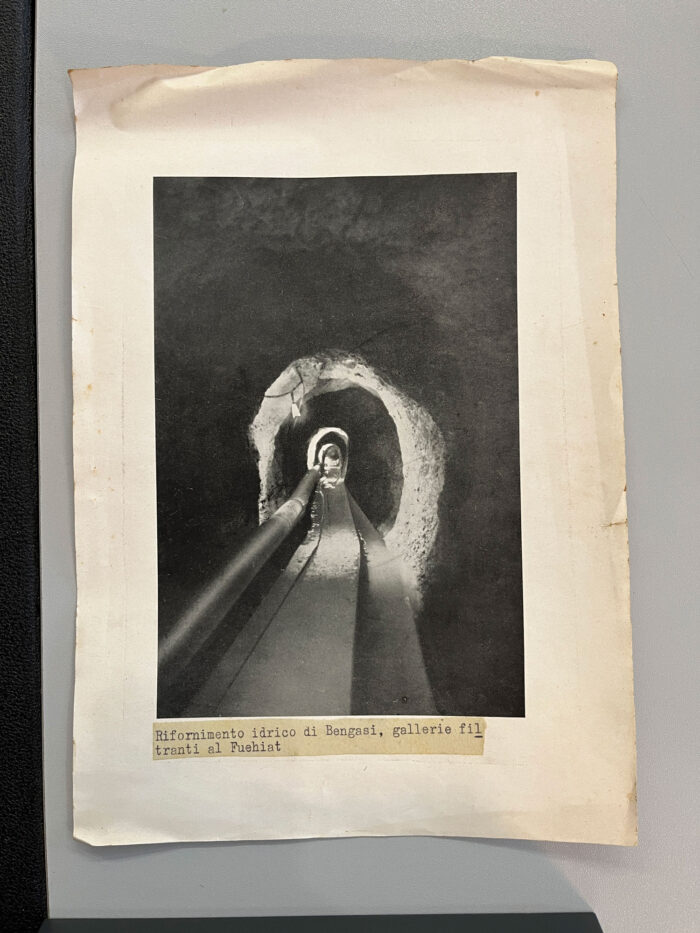

The violence of the images lay in the erasure and the absence of evidence and uncanny arranged motifs to convey an imaginary of territorial emptiness and untamed wilderness foregrounding the colonial binaries and othering. The redundancy of these motifs is disturbing. Many photographs showed the extractive artillery deployed in Libya to extract oil and water.

Interestingly, in the beginning, the Italians were looking for oil, and they found water. That’s why I call it extractive artillery because it is the same military and paramilitary infrastructure put in place to extract resources. The extractive machinery used for oil looks almost identical to the one used for water; the only things that would slightly change between these infrastructures are some specific components, depending on the nature of the discovered reservoir.

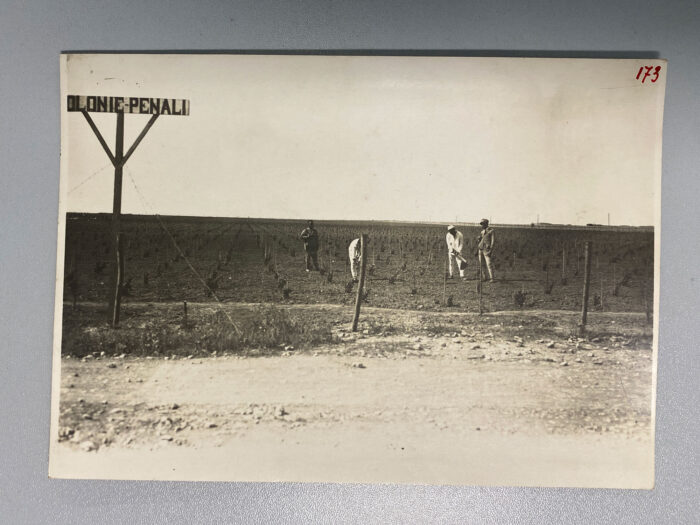

Here, I’m interested in the aestheticization of technologies. Many photographs we found, actually all the archival material, which is propaganda material, convey the Western imaginary of progress, modernity, and order: an imaginary representing the Libyan colonized subjects as to be tamed and civilized. The latter is illustrated almost as a leitmotif of the colonial photographic propaganda: forced labour as an abundant human resource to extract and exploit the land and water they used to steward.

In order to put in place this extractive, capitalist, colonial project, the Italian administration tried to erase any form of indigenous knowledge system. The partial erasure of this knowledge made the exploitation of landscapes, waterways, rivers, and habitats of humans and more-than-humans possible. Here, Libyan oral practices, such as poetry, were fundamental to resisting settler colonialism and the erasure of land and water practices. And it’s exactly what is missing in the archival photographs.

For the land to be tamed, the Italians subjugated not only the organized Libyan resistance but also all bodies carrying ecological cosmologies documented in oral practices and rituals. Erasing bodies means erasing a long lineage and heritage grounded in ancestral oral history and ultimately erasing tangible land and water practices—it did not succeed. Despite the capitalist and consumerist model, oral documentation and practices still resist. Returning to Vishmidt, this is about making holes in the infrastructure and challenging narratives and methodologies, which is very much about decolonial practices reconfiguring agencies and ontologies.

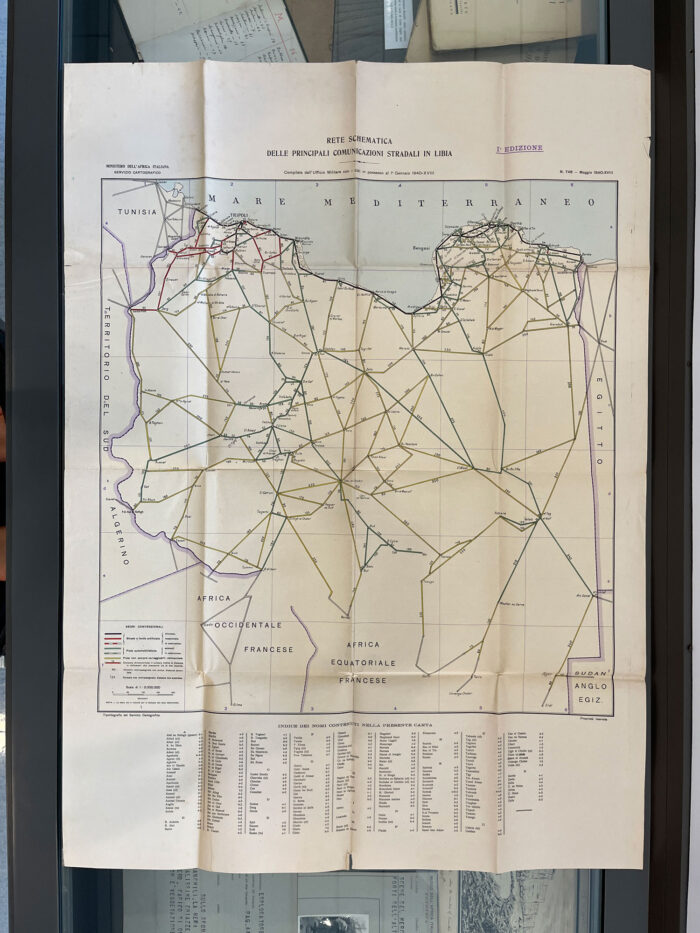

To the photographs, we can actually juxtapose the documents we found at the State Archives in Rome, which are biopolitical evidence, completing their absence in the photographic frame. When looking at colonial policies and land reclamation practices, the nation-state is at the core of it and enables a postcolonial inheritance of governance and policy-making. So it was no surprise during our fieldwork to hear about actual land policies, taxation, and irrigation systems based on and dating from the Ottomans, Italian colonization and the British and French occupation after WWII.

Here, it is the perfect Marxian marriage between extractive infrastructures as the backbone of the capitalist mode of production and the “accumulation of (colonial) knowledge and skills of the general productive forces of the social brain absorbed into the capital” in a vicious circle during the colonial and in the making of today’s postcolonial. Colonial human-non-human binaries have been internalized and manufactured, transforming natural resources into the productive machinery to boost the extractive cycle.

Adelita Husni Bey: I was thinking about how this connects beautifully to something you mentioned—Le Milizie del Bosco. The persistent myth of the desert as empty, lifeless, and uninhabited still shapes perceptions of Libya today. I recently spoke with someone after returning from Libya, who asked But isn’t it just a massive desert where no one lives? This imaginary ties directly to what we now call “adaptability”—a techno-fetishist drive to reshape landscapes for capitalist development, whether through greening the desert or policies of terraforming flood-prone areas. It’s the same logic that underpin’s Elon Musk’s fantasy about living on Mars.

The Milizie del Bosco were indigenous groups, overseen by Italian settlers, forced to plant grid-like hedges of specific grasses in pre-desertic areas to halt desertification and create arable land. This mirrors contemporary policies that seek to manipulate landscapes under the guise of environmental adaptation. I was reminded of the FAO report I shared with you, commissioned under the king and published around 1969, just before or as Gaddafi took power. It extended the Italian (and earlier Ottoman) discourse on land tenure and settlement, reinforcing policies that sought to sedentarize nomadic populations well into the late 1960s.

This also connects to your point about the erasure of bodies—how, in the archive, we found just a few scattered images of the concentration camps, almost as if they had slipped in by accident. There’s so little documentation, despite the staggering fact that nearly a third of Libya’s population was killed during that period.

To move toward a close—though it’s difficult with such a rich and layered subject—I keep returning to the idea of the colonial continuum, which you always push me to think through. Perhaps it would be interesting to conclude by reflecting on its specificities, as Emilio Distretti articulates them.

Shehrazade Mahassini: Emilio Distretti’s work on the coloniality of Italian architecture and infrastructure is brilliant. He wrote a paper about the Libyan Coastal Highway or Litoranea Libica, built in the late 1930s and retraces historically its ideological and political instrumentalization from its colonial inception until the postcolonial era and its neocolonial entanglement. Our research interests and decolonial methodologies overlap here, and I’m extremely grateful for his insights and support. Water infrastructures in Libya have similarities but differ in their postcolonial articulation. Many built during the colonial period were part of agrarian land reclamation schemes, which were unsuccessful in terms of crop yields and the imaginary the Italians were proclaiming to achieve. Nevertheless, taming and greening the desert was part of a fragile Italian nation-building scheme extending to the colonies, echoing the drying of the Pontine Marshes in Italy.

In postcolonial Libya, the Great Man-Made River Project and the many water infrastructures built post-independence are informed by the accumulated colonial knowledge transfer but differ in their articulation as Libya’s emergence as a petrodollar regime made it possible to build such a gargantuan project. In Libya, as in many young North African independent countries, colonial land reclamation practices never left, and in the name of modernity and national unity, large-scale projects emerged as freedom nationalist symbols. The nation-state depicted the existing tribal system as pernicious, and the transition from Italian colonial extractivism to a postcolonial global one intensified the progressive erasure of Indigenous land practices, fuelling the climate crisis in a vicious circle. Striking examples are international institutions such as the FAO or the World Bank, which launched massive surveys to legitimate ongoing forced sedentarisation of nomadic and semi-nomadic communities.

An incredible scholarship that needs to be emphasized when researching Libya and the colonial legacy of the SWANA region, in general, is Ali Ahmida’s body of work, as it allows us to understand the colonial continuum in Libya by dissecting the modus operandi of Italian colonial historiography. He not only demonstrates the archival violence perpetrated by the former fascist Italian colonial regime but challenges research methodologies in foregrounding his scholarship in Libyan oral history and challenging the nation-state and its instrumentalization in postcolonial Libya.

The colonial continuum is here to be understood in rhizomatic layers, which mutate and penetrate all dimensions from the domestic, through the local and regional, until the global and planetary—the invasiveness of extractivism is a capitalist and neocolonial issue at a planetary scale. So, how do we deal with this colonial legacy and water infrastructure in times of ecological and climate collapse?

Adelita Husni Bey: Yeah, I was also thinking about Emilio’s paper and how he discusses the ironically titled “Treaty of Friendship, Partnership, and Cooperation” between Italy and Libya, signed in 2008 and designed to stop migration to the Italian coast. In reality, this meant Italian taxpayer money funding what international bodies have described as torture camps—detention centers meant to keep migrants away from Europe. This reflects how infrastructure, like the Litoranea—coastal highway built by the fascists in Libya—extends European sovereignty beyond its borders, embedding imperialist ideologies into policy through infrastructure. Before Italian colonization, much of Libya’s population, especially in the interior and desert regions, relied on long-established routes shaped by nomadic and semi-nomadic lifestyles, caravan trade networks, and localized paths between oases. The Litoranea introduced a rigid, centralized infrastructure that disrupted these traditional patterns by prioritizing European-style road transport over indigenous mobility systems.

The rapid rebuilding of Derna after the catastrophic dam collapse is another example of this unbroken chain of imperialist logic supplanting traditional epistemologies which are renarrated as old and useless. The dams, which failed under three times the annual rainfall in just a few hours, were vulnerable from the start, because of their position—in a valley prone to flash floods running through a heavily populated city. Yet, instead of questioning their necessity, the response is to rebuild—reinforcing the same flawed infrastructure that collapsed under the weight of the very crisis capitalism has created: climate change. Scientists and hydrologists have argued that these dams should not be rebuilt, pointing instead to long-standing ways of managing water and land sustainably that may have averted this tragedy all together: letting the rivers flow and not building near riverbeds that can flood.

LOCALES asked me to speak about the idea of “fragments,” but I find myself at odds with that idea. Everything we’ve discussed points to a continuum—historical and ideological lines that persist, shaping our present. Instead of fragmentation, we’re seeing cycles: capital, development, and increasingly rapid destruction. Unless we learn from the ways people have long cared for their environments, we will remain trapped in these escalating cycles.

Shehrazade Mahassini: I mean, if we look at fragments from a new materialist perspective and try to dissect them with all ramifications and relation to modes of production and reproduction, and so forth, we can and should. However, if it is as traditionally understood, taking a fragment of a chain and trying to understand and deal with it, we are fooling ourselves and perpetuating a symptom-relieving strategy. And it’s very much what is happening at the very moment we are talking. Climate collapse cannot be handled without addressing climate justice and its entanglement with settler colonialism, neocolonialism, patriarchy, racism and selective solidarities. In terms of water extraction and infrastructures, the adaptation of infrastructure to climate change is the techno-fetishist claim that we can survive and continue to extract and exploit endlessly, and it is happening everywhere.