Walls That Are All Margin

Ute Müller’s work explores the perception of space and the role of the observer

Ute Müller, winner of the Kapsch Contemporary Art Prize 2018, makes installations that create a dynamic interplay between painting, objects, and architecture, breaking away from stale concepts of the work of art and forms of perception. Walls and plinths are removed from their usual architectural functions as frames and backdrops, themselves becoming motifs that shape both work and its perception, while images and objects recall real everyday matters in spite of their high degree of abstraction. This exhibition leads to a game with allusion. The unframed paintings have overlapping colors that seem to dissolve in the dark backgrounds, whereby they refer to the painted and drawn elements of the wall elements that dynamically reach into the exhibition space. Both following texts have been first published in the catalogue accompanying the exhibition at Mumok, Wien.

Exhibition view, Ute Müller. Kapsch Contemporary Art Prize 2018, mumok Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, Photo: Klaus Pichler © mumok/Ute Müller

“In the exhibition: walls that are all margin. Is it like hair falling down a back? Another kind of margin, mask. We see the line where it stops, the breathing back; the room it parts. We are all parts, and thus we depart (»so abstract«), displaced into yet another form and place. The space (»space«) sculpted (»sculpted«) or inverted. We follow the lines with our eyes, then our bodies, all of our material abstractions. Watching the walls streak down, hover there, their pale look, so much static, we take in the divisions, the ends, the emptiness that is formed. We size up the self: our body, this wall, that body, some object, some thing folded (into itself or over some other self), a series of curves, the mean medium of collapse, subtle constellations of subtle exiles. We assume a relationship to—what—to the spatial field: its disparities, its totalities, its subtractions, its medians and occupiers. We relate to form, its lack, then transform ourselves in relation to what it provides and what it does not (»what it does not«). We let the walls cross and delimit us. Layers and elisions of thinking, of space, of architecture, of material, of formlessness, then of even less. Pale page, pale room, pale wall, pale—what—mind. A kind of metallic stare.”—Excerpt from Solid and Soft Version of Same, or Give More Body to It (Letters from Ute Müller) by Quinn Latimer

Exhibition view Ute Müller. Kapsch Contemporary Art Prize 2018, mumok – Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien. Photo: Klaus Pichler © mumok/Ute Müller

Exhibition view Ute Müller. Kapsch Contemporary Art Prize 2018, mumok – Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien. Photo: Klaus Pichler © mumok/Ute Müller

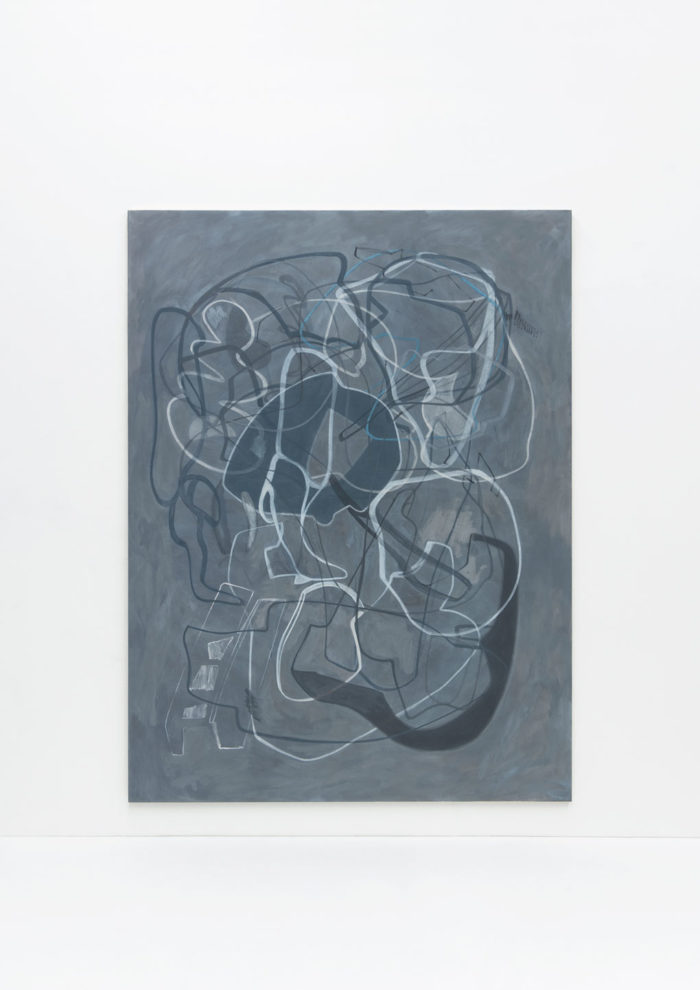

Ute Müller, Untitled, 2018. Egg tempera on canvas. © Ute Müller

“Ute Müller’s recent paintings demand an intensive durational viewing. After registering a rectangular field of gray(s), the viewer’s eyes begin to trail the twisting and interlacing lines running on its surface at varying speed, direction, and depth while noticing their subtle chromatic and textual differences. Then, in the web of those multidirectional lines, one gradually (or abruptly) notices diverse forms, enclosed or half-open, that overlap, connect, or echo with each other without necessarily coalescing into a structurally unified whole. Some of these forms are reminiscent of bodily (but not necessarily human) organs surrounded by a network of nerve systems or blood vessels, while others look like architectonic structures carrying distant memories of their long-lost functionality. (…)

This is one of the lessons that Müller’s paintings can teach us, for her paintings activate multiple layers of our »memories«—conscious and unconscious, visual and kinesthetic, intellectual and emotional—which are constantly forming and de-forming our perception; that is, those »memories« are the very medium/support of our perception in its present progressive tense rather than an additional element grafted onto it. Our perception, while viewing her works, seems to unfold in an undefined heterogeneous »volume« whose spatio-temporal density escapes any clear description and analysis.

Exhibition view Ute Müller. Kapsch Contemporary Art Prize 2018, mumok – Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien. Photo: Klaus Pichler © mumok/Ute Müller

Exhibition view Ute Müller. Kapsch Contemporary Art Prize 2018, mumok – Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien. Photo: Klaus Pichler © mumok/Ute Müller

Exhibition view Ute Müller. Kapsch Contemporary Art Prize 2018, mumok – Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien. Photo: Klaus Pichler © mumok/Ute Müller

Exhibition view Ute Müller. Kapsch Contemporary Art Prize 2018, mumok – Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien. Photo: Klaus Pichler © mumok/Ute Müller

But, curiously, the concept of »volume«—whose etymological Latin origin, volumen, signifies a roll of manuscript—can be a guiding light for us. We can still hear the echo of that origin when we talk about a »volume« of a magazine or some author’s collected writings. Unlike the related concept of »mass,« a volume is not necessarily filled with inert matter; although it primarily refers to spatial quantity, it also implies a certain level of elasticity—as in the volume of a sound—while being capable of containing numerous layers of writings and images within that elastic space. A volume can be weighty but also airy, dense but porous, cloudy but also diaphanous. These contradictory aspects are »bound« together by distant memories of volvere (Latin)—to turn, roll, or wind—to form a precarious whole that is always on the verge of entropic dispersal. It is this obscured sense of the volume-in-suspension, as it were, that Müller’s paintings seem to set in motion in their galaxy of translucent grays.”—Excerpt from Volume in Gray—Ute Müller’s Recent Paintings by Michio Hayashi