Vita Nuova

New Issues for Art in Italy 1960-1975

For the first time in France since 1981, the MAMAC of the city of Nice presents a major project dedicated to the Italian art scene between 1960 and 1975. Bringing together 130 works by 60 artists, Vita Nuova offers an unprecedented perspective on a major art scene.

The exhibition is curated by art historian and specialist in Italian art Valérie Da Costa. The following text is an excerpt from the catalogue Vita Nuova. Nouveaux enjeux de l’art en Italie (ed. MAMAC-Snoeck, 2022, p. 12-25).

Between the early 1960s and mid 1970s, Italy experienced a particularly fertile and exceptional period, inextricably linked to the richness of cinema and literature of the period. Paradoxically, since the exhibition held at the Centre Pompidou National Museum of Modern Art (Paris) in 1981—Identité italienne. L’art en Italie depuis 1959 curated by Germano Celant (1940-2020)—there has been no major overview of this remarkable art scene in France. Between the early 1960s and mid 1970s, Italy experienced a particularly fertile and exceptional period, inextricably linked to the richness of cinema and literature of the period.

Paradoxically, since the exhibition held at the Centre Pompidou there has been no major overview of this remarkable art scene in France.

(…)

An exhibition beyond Arte Povera

The exhibition Vita Nuova. New Issues for Art in Italy 1960-1975 is not a continuation of the Arte Povera craze, from which France and its public collections have not escaped, but presents a much broader artistic scene. It focuses on a diversified, non-exhaustive landscape, composed of a selection of artists, some of whom have been forgotten in Italian art (particularly women artists), whose work is being exhibited for the first time in France and recently rediscovered in their own country.

These artists were born between the 1920s and 1940s and are active in Florence, Genoa, Milan, Rome and Turin. They are bearers of new ways of understanding and making art and illustrate a form of vita nuova (“new life”), a title borrowed from Dante’s eponymous book (Vita Nova)—the first text to have been written in lingua volgare (i.e. Italian) and not in Latin, dating from the late 13th century.

Vita Nuova shows fifteen years of creation in Italy. From 1960, the date of the first solo exhibitions of this young generation of artists, to 1975, the tragic death of the writer, poet and director Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922-1975), to whom the installation in the last room is dedicated. Created by his childhood friend Fabio Mauri, Intellettuale (1975) is the memory of the performance held on 31 May 1975 at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Bologna, during which Pasolini received the projection of his film The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964) on his bust, which served as a screen.

In connection with the profound transformations of international artistic practices in the 1960s, Italian culture was marked by numerous societal and political issues that were reflected in artistic creation.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the transformation of Italy (industrialisation, consumer society, political instability) led to new modes of representation, which in turn were influenced by the mass media (television, radio, press, advertising, etc.) and changed the way in which artists revealed their times.

Faced with these societal upheavals, artists are turning to a form of degrowth art by choosing to look closely at the nature they represent with primary or artificial materials or by taking action.

They also place the body at the centre of their practice. The body appears to be a medium that runs through the creative processes and involves, in particular, a reflection on the memory of the body, the question of gender and participatory issues in the public space.

The exhibition, which does not adopt a chronological but a thematic point of view, is organised around three major themes (society, nature, the body) considered in a porous and transversal manner in order to show the circulation of artists, forms and ideas between visual, ecological and physical issues.

A society of images

Italian society in the early 1960s was marked by the “miracolo economico”, which had been introduced in the early 1950s, transforming an agricultural economy into an industrial one.

In 1957, the FIAT 500 was launched. Six years later, in 1963, the province of Rome celebrated the 600,000 car number plates, a symbol of the consumer society. The Autostrada del Sole (Motorway of the Sun), linking Milan, Rome and Naples, was inaugurated in 1964, providing new images of the Italian landscape. By 1965, fifty percent of the Italian population owned a television set.

Italian cinema was in its golden age. Michelangelo Antonioni directed L’Avventura (1960), La Notte (1961) and L’Eclipse (1962) back to back, Federico Fellini, La Dolce Vita (1960), Luchino Visconti, Rocco and His Brothers (1960), Mauro Bolognini, Il Bel Antonio (1960), Pier Paolo Pasolini, Accattone (1961) and Mamma Roma (1962), Francesco Rosi, Salvatore Giuliano (1962).

Along with Cinecittà, Rome is a production centre not only for Italian and European films, but also for American films; the city is called “Hollywood on the Tiber”. Gianfranco Baruchello and Alberto Grifi recovered 150,000 metres of reels from which they took and edited extracts, resulting in Verifica Incerta (Disperse Exclamatory Phase) (1965) one of the most surprising found footage films in the history of experimental cinema.

Film stars also appear in the works of Mimmo Rotella (Marilyn. Il mito di un’epoca, 1963), Fabio Mauri (Marilyn, 1964), and Cesare Tacchi, who depicts Monica Vitti and her cat (Monica e il gatto, 1965).

Italy’s capital became the country’s artistic centre. Its ancient and renaissance past is revisited in the paintings of Renato Mambor (Zebra e Colosseo, 1965), Franco Angeli (Testa di lupa capitolina, 1964) and Tano Festa (Michelangelo According to Tano Festa, 1967).

These were the beginnings of a young generation of artists (Franco Angeli, Tano Festa, Giosetta Fioroni, Jannis Kounellis, Renato Mambor, Pino Pascali, Mario Schifano…) identified by the critics as the “Scuola di Piazza del Popolo” because they met at the Caffé Rosati and the La Tartaruga gallery in Piazza del Popolo. They made a name for themselves by exhibiting in the young Roman galleries (La Salita, La Tartaruga, Trastevere), which soon played a central role in artistic life.

(…)

Jannis Kounellis (La Notte, 1965), Titina Maselli (Acqua minerale, 1963; Fili nel cielo, 1969), Mario Schifano (Tutta propaganda, 1963), portray this contemporary city with its signs, lights and advertisements. When Giosetta Fioroni (La ragazza della TV, 1964), Marisa Busanel (With, 1962), Lucia Marcucci (Miss Viaggio, Il Fidanzato in fuga, 1964)—the latter engaged in visual poetry in Florence—and then, a few years later, Rosa Foschi (Ma Femme, 1970), represent the image of women and their place in an Italian society largely governed by patriarchy with humour and determination.

With her first series of photographs, which took as their subject the transvestite and transsexual community in the port of Genoa (I Travestiti, 1965-71), Lisetta Carmi took a precursory look at the question of gender and prostitution in Italy; the theme remained totally innovative in a country dominated by the Catholic religion and the weight of the papacy. Her vision is similar to that of her contemporary Pier Paolo Pasolini, who questioned the sexuality of Italians with Comizi d’amore (1964).

In this remarkable documentary, which has the background of those years, Pasolini explains that he hopes to discover a “cultural and social miracle”.

Comizi d’amore crosses all the social classes and regions of Italy, from north to south. Pasolini interviews peasants, workers, students and teenagers about desire, sex, marriage, children, divorce, prostitution and homosexuality. The poet Giuseppe Ungaretti (1888-1970), the writer Alberto Moravia (1907-1990), and the psychoanalyst Cesare Musatti (1897-1989) punctuate this true societal investigation, which takes place after the Merlin law of 1958, as authority figures.

Faced with the influx of internal migration from the south to the north (in 1967 Turin recorded the arrival of almost 60,000 emigrants), the cities experienced housing and integration problems; this was the beginning of a series of strikes in the north of the country. Economic prosperity gradually began to decline from 1967 onwards and the country, marked by a succession of governments, from the Christian Democracy to the Italian Socialist Party, experienced social and political instability from the late 1960s.

The spring of 1968 was marked by strikes by FIAT workers in Turin and by student demonstrations in Rome, Venice and Milan, which occupied the Milan Triennale and the Venice Biennale. With his Abbraccio eterno (1968), Franco Angeli took a photograph of partisans in 1945 to illustrate the revolutionary context of May ’68. And Ugo Nespolo designed two sculptures in the form of stamps bearing the words “Power” and “Violence” (Power Violence, 1968).

But it is above all 1969 that is remembered with the tragedy of the attack in Piazza Fontana in Milan on 12 December, in which sixteen people were killed and eighty-eight wounded as a result of the explosion of a bomb planted by the extreme right in the National Bank of Agriculture, while at the same time other bombs exploded in Rome. A few days later, the railway worker and anarchist activist Giuseppe Pinelli, questioned about the attack, was found dead under the windows of the Milan police headquarters.

This was the beginning of the years of darkness that lasted until the early 1980s. Fascist groups even tried to seize power, as in the case of the Golpe Borghese (Borghese Coup d’état) which took place in Rome in December 1970. Artists reacted. Luciano Fabro made a map of Italy in tatters (Italia del dolore, 1975), Gianfranco Baruchello painted the hanging by the feet of Mussolini in Piazzale Loreto in Milan in 1945 (Nello spazio della violenza, 1973). Fabio Mauri dedicated his first performance to this question: Che cosa è il fascismo (1971). He staged a traumatic experience linked to his personal history by simulating and re-enacting an enlistment ceremony (Ludi juveniles) organised by the GIL (Gioventù Italiana del Littorio).

(….)

Reconstructing nature

In this fast-paced industrialised world, there is a growing awareness of the excesses of the consumer society. Nature appears to be a central subject for certain artists who, seeking a form of degrowth, create with it or interpret it using natural or artificial materials.

Pino Pascali questions its reconstruction and affirms the free interpretation of this theme in a series of works that he entitled “ricostruzione della natura” (reconstruction of nature).

Laura Grisi records the wind (Wind Speed 40 Knots, 1968) or, sitting on a beach, counts the grains of sand to materialise time (The Measuring of Time, 1969). Marinella Pirelli observes and plays with sunlight (Sole in mano (o appropriazione, a propria azione, azione propria), 1970-73). Luca Maria Patella with Terra animata (1967) performs a succession of actions in a field to “animate the earth”, delineating and illuminating it with sunlight. Their films affirm that creating outside the studio is not the only preoccupation of the well-known Anglo-American Land Art adventure and that at the same time, in Italy, artists share common concerns, but which take other aesthetic forms, more intimate, much less spectacular and yet necessary.

It was these primary and essential materials: light, earth, water, air and fire, which challenged the art scene of those years. Like the gallery owner Fabio Sargentini, who in June 1967 organised Fuoco, Immagine, Acqua, Terra in his Roman gallery L’Attico, an exhibition that prefigured the adventure of Arte Povera, which was born a few months later, in the autumn of 1967, (“Arte povera – IM Spazio”) at the La Bertesca gallery in Genoa, and from which the aforementioned artists are strangely absent. (…)

Mario Ceroli’s wooden sculptures (Fiori, 1965) and Mario Merz’s installation works, which take up the primitive habitat of the igloo (Acqua scivola, 1969), aim to remake nature in its strictest elementality. Pino Pascali, for his part, reconstructed the ploughed fields of his native Puglia (Campi arati e canali di irrigazione, 1967) using earth and water, materials that he brought into his work from 1967 onwards, and which here redraw the modularity of landscapes worked by man.

Artists and designers share a common interest in the forms of nature. At the intersection of design and art, Piero Gilardi, who made a name for himself in 1965 with his Tappeti-Natura (Nature Carpets), on which the designer and friend Ettore Sottsass published an initial analysis in the magazine Domus, asserts a functionality of art.

Nature, reconstructed in polyurethane foam, is transposed into domestic spaces; it becomes a living element that can be sat on (Tronco sedile, 1966) and worn (Vestito Natura-Anguria, 1966). Contemporaries of Piero Gilardi, the designers of the Gruppo Strum: Pietro Derossi, Giorgio Ceretti and Riccardo Rosso created the Pratone armchair in 1971, which represents a square of artificial grass, inviting people to place a “piece of nature” in their homes. The Florentine group of architects, Archizoom, designed the Superonda sofa (1967), whose wave-like shape, covered in white PVC, tilted horizontally, is similar to Pascali’s Cascate (1966).

This desire to bring art into life intersects with the ideas of the American philosopher John Dewey, whose book Art as Experience (1934) was translated and republished in Italian in 1964. John Dewey’s thought was particularly successful in Italy in these years and met with the theories of Herbert Marcuse and his One-Dimensional Man (1964), which was translated in 1967, a text that questioned the influence of urban and industrial culture, consumer society and the mass media on the construction of human identity.

(…)

The Body’s memory

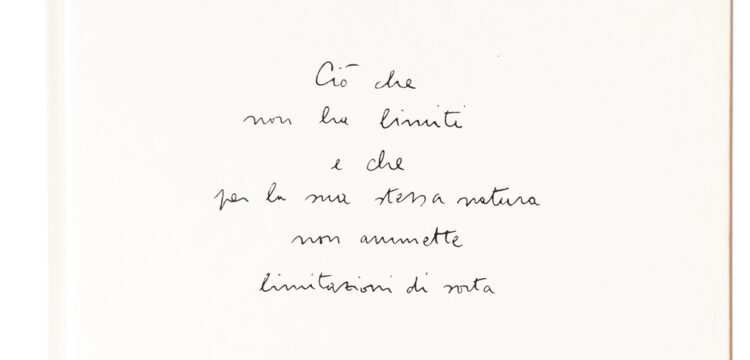

“What always speaks in silence is the body” (Ciò che sempre parla in silenzio è il corpo), noted Alighiero Boetti in 1974 in a filmed ambidextrous performance, writing this sentence with his right and left hands, spreading his arms to his measurements. Sculpture is the memory, the trace of the body, just as painting is that of the gesture.

At the beginning of the 1970s, many artists used their body as an element of reference, of measurement, of transvestism, and not as a material with which to interact, unlike the issues at stake in Body Art. It is a conceptual body whose absence Vincenzo Agnetti evokes through a sign and words (Abitato dalle cose e dal respiro, 1971).

The Eigenschriften series (1968-1973) that Irma Blank, an Italian by adoption, began at the end of the 1960s in Sicily and then in Milan is similar to a meditative exercise in which writing, now a sign, fills sheets of the same size (70x50cm) to deliver an intimate exploration of oneself that goes as far as the exhaustion of the gesture and the clarification of the mind. This experience can be compared to that of the gesture made by Giorgio Griffa at the same time in his “performative” approach to painting. Placed on the ground, the artist physically enters the space of the canvas to leave traces and memories of his actions, which give an account of his gestural process where “the abandonment of the hand”, “mental passivity”, as he puts it, creates sequences of signs that constitute rhythms (Obliquo, 1971; Verticale orizzontale, 1972; Linee orizzontali, 1974).

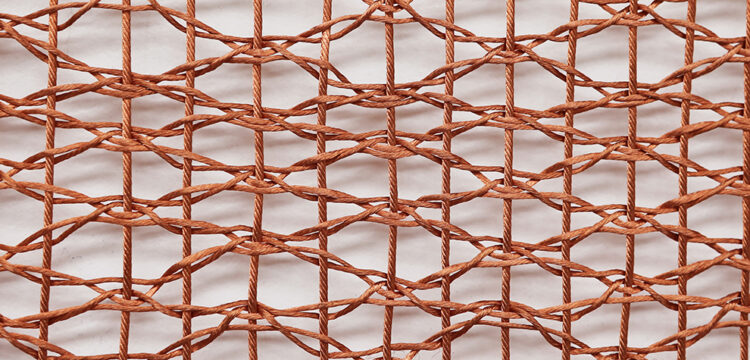

Remembering Leonardo da Vinci’s Uomo Vitruviano (c. 1490), whose measurements create his own space, Giulio Paolini, in his studio, grasps a white canvas of his own size with his arms spread out (1421965, 1965) and Paolo Icaro, in the early 1970s, begins a series of barely perceptible sculptures in metal and plaster (Misura della mano sinistra, 1971; Punti mano sinistra chiusa, 1974) that testify to the measurement of his own body. This referent body is also the one that runs through the delicate creations of Marisa Merz, where her Scarpette (1975), small shoes made to the size of her feet, first knitted in nylon and then in copper, were made for her exhibition at the L’Attico gallery (Rome) in 1975. It is an absent body, as is the face of Gilberto Zorio (Autoritratto, 1972), which appears in an animal skin, or the actions of Eliseo Mattiacci (Rifarsi, 1973), who makes his face disappear by gradually covering it with clay.

During the same period, Ketty La Rocca’s filmed or photographed hand games (Appendice per una supplica, 1972), Giovanni Anselmo’s projections (Particolare, 1972), which propose receiving the word “particolare” (detail) on one’s hand, or Michelangelo Pistoletto’s mirror paintings (Quadri Specchianti) and mirror sculptures (Tavolo diviso, 1975) propose a participatory experience of the work.

Coming from a painting background, Carla Accardi began in 1965 to change her medium by painting on transparent plastic sheets (sicofoil). This material led her to think about the opening up of painting in space and to create installations to be experienced (Tenda, 1965-1966; Ambiente arancio, 1967), including Cilindrocono (1972), a project for a transparent cylinder into which visitors are invited to enter, which was not realised until the end of her life in 2013.

(…)

Luca Maria Patella’s anthology film (SKMP2, 1968), synthesises the actions of the four artist friends (Kounellis, Mattiacci, Patella and Pascali) in the space of the gallery (L’Attico), of the studio, in the city or in nature. A possible repertory of personal or collective actions that joins for the latter the numerous projects of public interventions of Franco Mazzucchelli in the urban space (Volterra, Como, Milan…) where his inflatable structures/sculptures are an invitation to a participative art with the aim of making a social art.

Thus, with all these proposals, Vita Nuova shows the diversity of Italian art of these fifteen key years whose vitality makes it an exception in the European and international artistic landscape.

A strongly regional country whose political and cultural history is characterised by its recent unity dating from 1861, Italy in these years was marked by the presence of numerous artistic centres scattered throughout the territory. It is therefore no coincidence that the most important group exhibitions of the 1960s-1970s outside Genoa, Rome and Turin took place in small provincial towns, in Umbria, Foligno (Lo spazio dell’immagine, 1967), on the Amalfi Coast Amalfi (Arte Povera più Azioni povere, 1968), Lombardy, Como (Campo Urbano, 1969), Marche, San Benedetto del Tronco (Al di là della pittura, 1969), Tuscany, Montepulciano (Amore mio, 1970) or Volterra (Volterra ’73). For, while testifying to a sustained circulation and display of contemporary creation throughout the peninsula, one can nevertheless hypothesise that this geographical dispersion has contributed to the invisibility of its international diffusion.