Unsteady Void

Marta Federici in conversation with bankleer (Karin Kasböck, Christoph Leitner)

Hidden Histories is a site-specific public program, consisting of performances, workshops, talks and urban explorations, meant to reflect on the cultural and historical heritage of Rome from a decolonial perspective. Conceived and curated by Locales, a curatorial platform founded in Rome by Sara Alberani and Valerio Del Baglivo, the project has just opened its second edition, which will run until the end of September and will present interventions by Stalker, bankleer, Josèfa Ntjam, Leone Contini and Daniela Ortiz.

Over the upcoming months, a series of interviews with the artists participating in HH 2021 will explore the issues addressed by the artistic interventions and in order to provide a broader context for each. The first appointment is dedicated to German artist duo bankleer and to their film Taumelnde Leere (Unsteady Void), a video essay made in Rome between winter 2020 and spring 2021, which will be presented at MAXXI Museum as part of the Hidden Histories program and within the event Villa Massimo in città, on Thursday June 24th 2021.

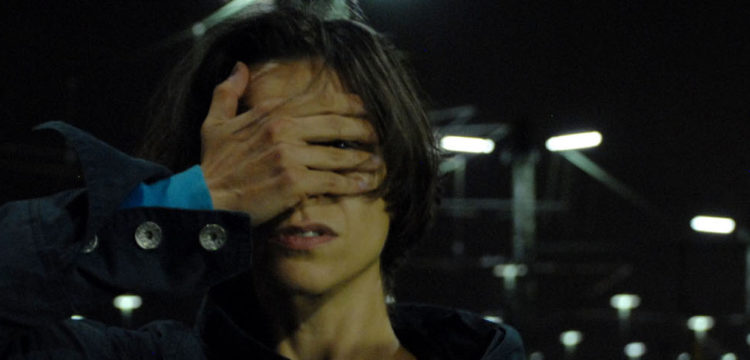

Taumelnde Leere (Unsteady Void) records the movements of two young women, who roam the city by night, moving from the suburbs to downtown. The conversation explores some of the topics emerging from their dialogue and actions, such as the relation with the public space and the possibility of inhabiting and reinventing it, the current ecological and financial crisis, and the desire of imagining new and potentially different futures for us human beings and for our planet. Retracing their first encounter along with other and more recent experiences, bankleer’s words contextualize their film in the framework of a long-standing research and explain their vision of art as a practice constantly aimed at responding to socio-political events.

Marta Federici: You have been working together for over 20 years. How did your collaboration begin?

bankleer: At the end of the 90s, many different artistic-activist groups in German-speaking countries joined forces in the fight “against privatization, gentrification and obsession with security,” to form the so-called inner-city-actions. In this context, we both organized a project space together with other artist friends in Munich. We were involved in actions, exhibitions, conferences and also co-produced the so-called a-clips, which were smuggled into cinemas between commercial breaks and the projection of the main film.

Afterward, we moved to Berlin and founded the artist duo bankleer in 1999. In parallel, we kept collaborating with different activist and political-art networks, such as nGbK, haben & brauchen, G8 TV, hybrid videotracks. Most recently, we have been collaborating also with station urbaner kulturen, a satellite of nGbK Berlin. bankleer is a project that addresses the aesthetic, urban, and socio-political relations between central and peripheral areas in Berlin.

During Hidden Histories 2021 you will present your new film, Unsteady Void, which was shot in Rome during winter 2020/2021. Can you tell us more about the genesis and development of the work, and about its title?

If we consider the way we consume, work, network, fix our planet, or live in a spirit of solidarity with refugees, we can understand how our view of a possible future has changed. Even before the pandemic, our perspective of the future was clouded, worn out, and in need of repair. With the Covid19 lockdown, the continuation of our daily lives, of our routines, has become questionable. The very foundations of our coexistence are experiencing a thorough alteration at a global level. Behind our backs, a worldwide event is piling up, exceeding our capacity of description and representation.

In this video essay, we listen into our speechlessness, in the face of an approaching future, which confronts us uncompromisingly with our past, without indulgence and with increasing intensity. The awareness of an existential threat to our collective conditions of existence pushes us to find different ways to deal with Earth’s critical and constantly changing situation, forcing us to reorient ourselves.

We wanted to challenge ourselves and take a new look at everyday self-evident things. Starting from some public spaces in Rome, where we currently live, we allowed ourselves to be entangled by textures, alliances, and ideas coming from the urban space. Thus, we developed a choreographic setting of sculptures, spoken text, sound and bodies that interweave with the city streets generating productive friction.

The film records two young people roaming around Rome, pervaded by a strange feeling of incomplete commonality with the world. Aware that their vocabulary is not enough to formulate a bright future perspective, they search—playfully and experimentally—for the Real, the formative effects of ideas made of words and actions. Driven by the willingness to put themselves in the other’s shoes, to try out different and unknown attitudes and voices, they overcome the distance that exists between themselves and the urban space through a silly, overstrained, poetic, indeterminate rough-doing and questioning. Their instruments are an oversized megaphone and a microphone on a very long cable, their bodies, imagination, and open-mindedness. They try to find out what happens when they interact with non-human actors, and with the environment that surrounds them. It is an interaction between hope and despair, that they must completely invent. With the help of the microphone, the two let monuments and other elements of the urban space speak; they play around the boundaries of things, meanings, and words.

In the film, we see three sculptural heads representing Angela Merkel (Chancellor of Germany), Mario Draghi (Prime Minister of Italy, former President of the European Central Bank), and Dutty Boukman (pioneer of the Haitian revolution of 1791). You already used them for other performances/actions in public space. When did you create the sculptures and how do you usually activate them?

We developed the characters as part of the Berlin “Herbstsalon” at the Maxim Gorki Theater. This second Berlin Biennale swings between exhibition, performance, and theatre, with a multi-perspective look at the notion of nation and identity.

When we made the sculptures, we were (and still are) reasoning on how we can no longer put ourselves in relation to the excessive growth of our economy. Our physical limits are exceeded by these unleashed dynamics: this inflated reality simply no longer fits into our heads. Therefore, we decided to take a closer look at this state of affairs adopting Mikhail Bakhtin’s perspective. In his book Rabelais and His World, published in 1964, the Russian literature and art scholar analyses the medieval novel cycle The Terrible and Horrible Adventures of the Giant Pantagruel and his Son Gargantua. The giants’ bodies he describes are not yet separated from the world around them: they are connected to it—they devour it and are devoured by it themselves. In that process, the edge progressively becomes the center, the inside turns inside out, while large and small reverse. Bakhtin sees in the narratives the very dynamics of the carnivalesque, an energy of alternative appeal that cannot be silenced. It awakens us to clouded horizons of expectation and lack of alternatives.

Our sculptures portray grotesque agents like politicians, revolutionaries, psychological figures, and philosophical models: larger-than-life heads that represent the German Chancellor Angela Merkel, the Prime Minister of Italy, former President of the European Central Bank Mario Draghi, and Dutty Bouckman, a pioneer of the Haitian Revolution of 1791, as well as the two archetypal figures, small A and WE Europe. They move in space in an uncharted manner, collide with each other, with the architecture, and with the audience, thus contradicting their habits and agreements. Their oversized figures oscillate between object and subject, between shapes and shapelessness: they are things that become speaking bodies that address passers-by, architectures, and places. They talk to themselves and each other or act directly with the visitors—providing a view of the world through the filter of personal obsessions. They stammer, shout, recite, sing, and rumble their way through their own contradictions, in search of a way out of a devouring and all-pervasive economy. They bring confusion, surprise, new thoughts, and doubts into rehearsed routines.

In the video essay, we also see the tohubassbuuh, a mobile sound system that can reach several places in the inner-city space and, through an over-dimensional microphone, make historical sculptures, monuments and memorials speak aloud, letting them temporarily becoming part of the performance / installation. The tohubassbuuh rearranges the relationships between public space, political-economic orders, and the people acting in them, bringing confusion into the well-rehearsed arrangement of consumption, tourism, and tradition.

The film was shot during lockdown. You were living in Rome at that time experiencing that absurd moment. Could you tell us more about the three specific locations of the film? We also see Rome’s suburbs in many scenes. How do peripheral territories meet your practice?

If we strive for a change of perspective with our work, we must give up our own comfort zone and start from difficult places where non-understanding, uncertainty and cracks begin. That could be anywhere enduring differences can be found, and it is usually at the edges, among the excluded, in the spaces in between. Basically, in places that have not yet been fully homogenized by neoliberalism and are incomplete.

While the possibilities for movement and contact were largely restricted, the opportunity opened up for us to use Rome as an alternative play space and stage. The film begins in a highly dense urban space, the tangenziale, a massive mobile infrastructure that ruthlessly snakes through established residential areas and archeological sites. On the one hand, that road is an absolute imposition for the residents thumped by noise and exhaust fumes, while on the other hand, the space under the rising roadway is comparable in size to that of a church. The performers then continue on the four-lane via La Spezia, one of several traffic axes leading to the center of Rome. The road, which slopes slightly and is usually heavily trafficked at exit barriers, offers quite different qualities becoming a place of exuberance, where gliding and dancing are encouraged. The third scene takes place in the elevated Piazza del Campidoglio, a place once favored by the gods and now a relic of transcendence, intertwined with the political sphere. From above, the two young protagonists look down on the city, which lies there and shouts silence back at them.

In your artist statement, you assert that your works “are often created through conflict-rich encounters with the audience.” Can you explain this sentence further? What kind of audiences do you usually address?

Every human being is equipped with a different sensory perception, which leads to the fact that others consider wrong something that we ourselves believe to be true and vice versa. Someone who disagrees with us is actually showing us that reality could be different from what we think. In this interaction, we see an important social energy that sets our reality in motion. Dissent is a force that helps us to transcend orders that have become entrenched and independent. Even if, on the other hand, it can also make us furious.

In the past few months, we have seen what happens when this social energy is missing. And how difficult it is for us as a society to get moving or reinvent ourselves culturally and socially without these intensities.

From our experience, we know how important it is not to immediately overcome states of tension by dissolving opposites and returning to our daily routine. Interruptions, the unplanned or contradictions open up a space for reflection and social awareness, shape horizons of expectation, and enable imaginative power.

The Hidden Histories program was born from the desire to question our cultural heritage and institutions, in order to decolonize the knowledge we share, and our imagination. What does “decolonize” mean to you? How do you interpret this verb?

An important figure in our ensemble, that we have already mentioned, is Dutty Bouckmann: a slave, voodoo priest, and catalyst of the Haitian revolution against the French occupation. According to the legend, the revolution was preceded by a voodoo ceremony led by Dutty Bouckmann, who was later beheaded by colonial soldiers during the uprising in 1791.

While the most advanced countries in Europe were reorganizing themselves in the “consciousness of freedom”, the abolition of slavery in the European colonies was left out as a matter of course. It was not achieved through the revolutionary acts of the French—but the slaves themselves successfully took this matter into their own hands: the idea of human freedom was thus no longer the monopoly of white people. In Haiti, the declaration of human freedom became universal.

As Buck Morss describes in her book Hegel and Haiti, a universal history requires a double liberation —that of historical phenomena/facts and that of our imagination. She argues for more porosity in our global social field, so that individual experiences, beyond collective identities, can bring human nature to light and loosen the cultural embeddedness that constrains us in the present. This is one way to take a step forward with decolonization: taking a step back and erasing the subjective point of view. Every view of reality is formed by our subjectivity and our resentments. Only when we manage in including our subjectivity, which pushes into the real, in the field of vision itself, a perspective opens up allowing us to look at things as they really are. Empty, omnipresent, silent, in mysterious peaceful joy.