Unlearning How To

Tactics for daily poetics: a conversation with Kayfa ta

In regards to both methodologies and content, Kayfa ta moves between public and private, pocket and exhibition format, shyness and loudness, insider and outsider, useful and useless, rest and revolution. The format tackles and challenges classical modes of reading and readership, knowledge production and distribution. In its didactic way of giving instructions, it poetically lingers on both intimate and collective urgencies, blurring the distinction between the two. In apprehending how to—do whatever we’re asked to, we unlearn the obvious. In being told how to—learn whatever skills are shared with us, any introvert tactic of daily resistance becomes a tool of mutual knowhow.

Federico has been collecting the whole How To series, as part of his private library OBA (Open By Appointment) and Giulia tangentially took part in the exhibition curated by Kayfa ta at the Beirut Art Center How To Reappear. “When thinking and talking about Kayfa ta, we always got the feeling it was a project we wish we had conceived ourselves.”

Federico Antonini and Giulia Crispiani: Can you tell us about Kayfa ta, what led you to start the project? Was it first an idea or did the idea come from already collected material? What was the (geopolitical) context within which you both conceived Kayfa ta? And why the handbook format?

Kayfa ta: The idea for Kayfa ta came in a flash. But also as a result of our cumulative experiences as artists, curators and managers/founders of independent arts initiatives and organizations in our respective cities (Amman and Cairo). Our interest in the expanded field of arts extends beyond our individual artistic practices, to the practice of others, as well as to the structures that support or constrict our practices and their access to public space. This concern with access—or lack of—to the sites and languages of art has been a concern we shared and expressed in several of our realized or unrealized collaborative projects, including Kayfa ta.

Kayfa ta began in 2012, and our first book came out in 2013. Clearly, these years are landmark years in the Arab World. From 2011 till today, people have taken to the streets to reclaim their agency and right of access to public space and policy-making. This outburst brought with it an overwhelming, public and private, drive to develop new modes of thinking, communicating, learning, unlearning, understanding, making, breaking, moving forward or backward as we think best. Many established figures and institutions lost their credence, many more sensitive and pertinent ones arose. The addressed and the addressees swapped places. And new languages were finding form.

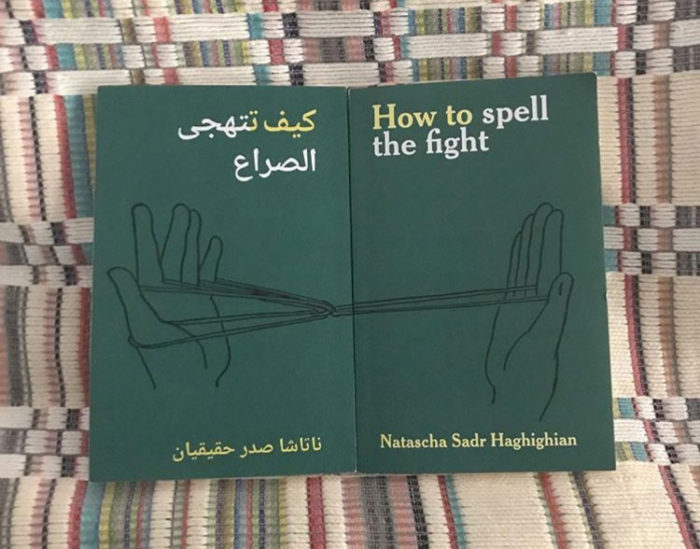

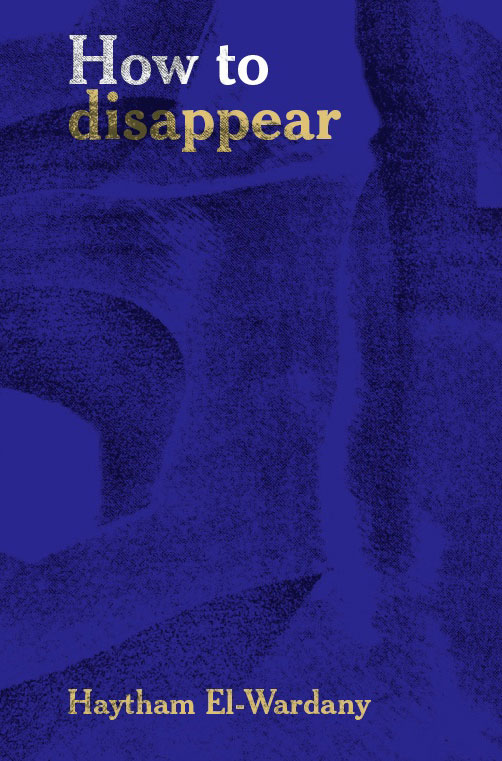

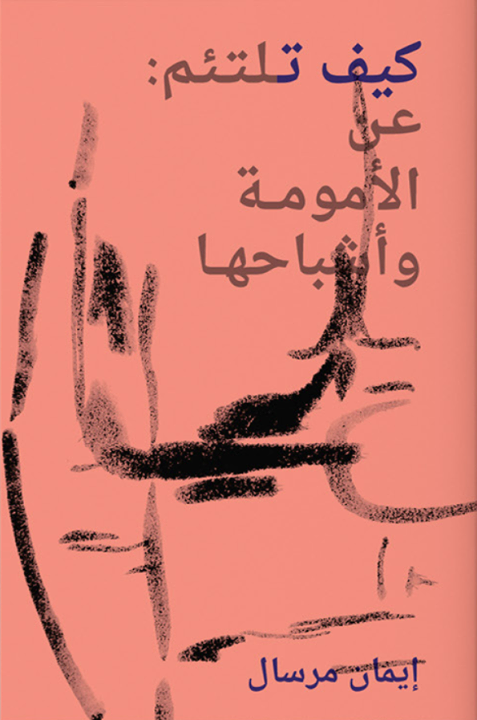

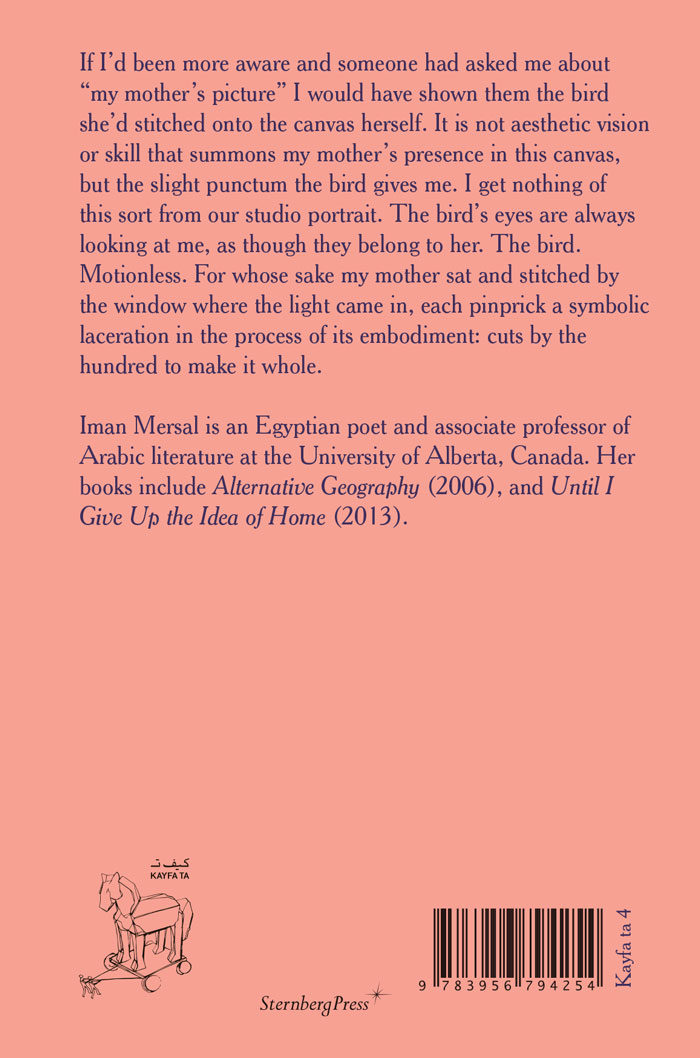

Kayfa ta, which in Arabic means “How to,” chose to adopt the popular format of How-to manuals—a familiar genre, cheap and handy, yet used here as a carrier of more experimental and non-prescriptive languages. The authors we invite are authors we believe have a sensitivity to the needs and desires of today. We ask them to propose a subject that they feel is of pertinence now, adopting the How-to format creatively, and to always keep a general audience in mind.

From your statement “We would like to place this series of monographs in the space between the technical and the reflective, the everyday and the speculative, the instructional and the intuitive, the factual and the poetic” you seem to be the inutile version—thus beautifully anti-capitalist, anti-work, anti-productivity—of the Whole Earth Catalog, for many a counterculture cult object, for many others, the beginning of the end, as the celebration and inspiration of the Silicon Valley ideology and so on. Is there any link between Kayfa ta and self-help/New Age? In How to imitate the sound of the shore using two hands and a carpet and in How to disappear there is a shift towards a sensorial focus. It isn’t a disappearance from society but into society and inside its sounds, as a guide for an introvert flaneur…

A guide for an introvert flaneur! That’s a very nice description, and does actually reflect very well a sensibility expressed in different ways by authors in our series. For example, in the latest Kayfa ta, How to remember your dreams by Amr Ezzat, he writes:

“Over several summer vacations I became utterly preoccupied with walking. Rather than remaining persistent in seeking the way, or in finding companionship, bouts of walking were to me like intermissions, and then turned into a hobby and an autonomous desire. I would wake up eager to go out and walk with no aim. A childhood friend joined me, at first laughing at the idea and then loving it… I don’t recall anything of our conversations those days other than that at the time I had read that Aristotle and his students were called the Peripatetics because they studied thought together as they walked and wandered about. I told my friend that we had surely walked more than they had, and he replied that it would be boring to walk with a teacher or philosopher who spoke to us about the meaning and import of things.”

To come back to the question of “utility,” Kayfa ta frames itself as a How-to series, thus situating itself in this far and wide “genre” of books which has taken many twists and turns across time in how they are written, read and used. Yet, Kayfa ta’s logo, a Trojan horse pulled by two people, is symbolic of how we relate to this genre, we use it as a shell, a carrier, to pass through it different kinds of writing, subjects, subjectivities, modes of reflection, address, publishing and circulation. What we consider valuable and useful, may very well be anti-capitalist, anti-work and anti-productivity, but it may also change with time and need, or it can be the thing and its opposite.

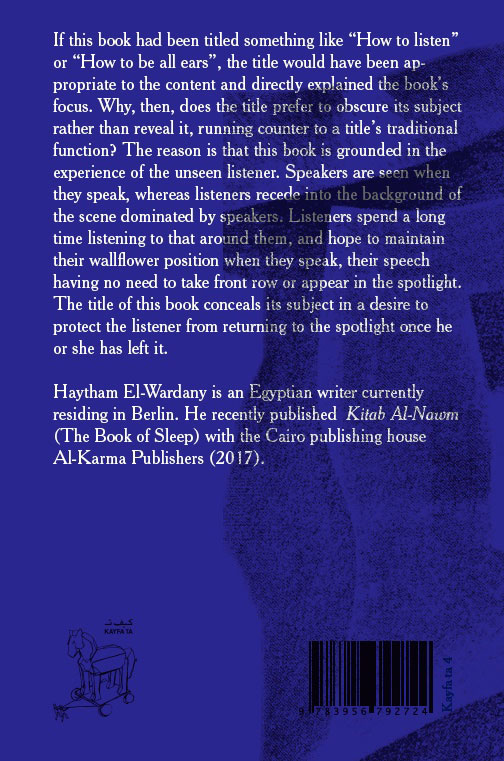

For instance, the first book in the Kayfa ta series, How to disappear by Haytham El-Wardany, was published in 2013, two years into the Egyptian revolution with all its fierce highs and lows, and not far before its imminent face off with a violent counter-revolution. The need to persevere, then and now, was a balancing feat. How to throw yourself, body and soul, into a collective movement, yet self-preserve. The titles of the exercises that Haitham develops through his book are telling: “how to disappear,” “how to reappear,” “how to listen to your inner voice,” “how to find meaning in dead time,” “how to change your frequency,” “how to join a group,” and “how to break with a group.”

How to collapse the distance between disciplines, practices and thoughts? Why do we need it?

What we try to do in this series is to invite authors from different disciplines and practices to respond to few formal parameters such as writing about a subject they feel an urgency for, or addressing a general public as much as they can in the hope of expanding language beyond specialization confinements. And we publish these different contributions in one book series, hoping that these different disciplines, thoughts, practices, authors and readers interface, if not in the same book, then across the arch of the series.

Kayfa ta seems to be constructed as a non-prescriptive instruction based artwork. The formats are indeed pocket-size and utilitarian. These booklets demand to be kept in pockets, although usually you would carry a utile guide. What’s the utility of evoking the sound of the sea with a carpet?

This book has a little back-story. Cevdet Erek wrote it when he was away from his home city of Istanbul, on an art residency in Alexandria, Egypt. He started writing it as a manual for his friend from Istanbul, who had also moved away from Istanbul to a landlocked country, and longed for the sea. He showed her how she can imitate the sound of the sea using just her hands and a carpet. Actually the carpet is also not necessary, one’s jeans can do too, and one can perform this either for oneself or for a bigger audience. So, part of what this manual does, in our view, is that it allows one to reproduce sounds from home by using one’s body, and other easily available tools. It opens prospects of creating a space of our liking, by reorganizing the sounds of the space we are in. A practical and poetic skill to have.

Kayfa ta seems to have interiorized in a constructive way some of the modalities of the Mittel-European independent publishing (Sternberg publishes you), yet dropping the coolness and shifting the research axis on the other side of the Mediterranean sea, or?

Well our primary focus was to publish in Arabic because we were responding to a contextual need, but we did not have a geographical focus as to the provenance of our authors or readers. Our series is published in both Arabic and English editions, distributed internationally, and so far we have published authors from Egypt, Turkey, Ireland, Germany, Lebanon and Russia. We have also worked with various publishing partners, including Sternberg and other Egyptian and Lebanese publishers, in order to facilitate the production and distribution of the series.

Having said that, we are of course close to the artistic and literary scenes of the Arab world, and are aware of the gaps in contemporary writing on art in Arabic. On the other hand, surveying book titles and prices in a visit to an art bookshop in Berlin, we also observed the limited presence of good creative writing from the Arab world, as well as the exaggerated prices of art books in general. Overpriced books on the one hand, and the absence of this variety of content in the arabic (art) library on the other, also reflected the publishing tendencies in both regions. It was partly due to these tendencies that Kayfa ta developed as an idea of becoming an affordable space for creative and arts writing for these and other locales.

We actually see in the iper-sensorial, and this attention to details, more of a strategy to say things otherwise, as a poetical metaphor, while the pocketability of the format seems to be favorable for faster and wider diffusion, as something to be passed hand-to-hand. What is the influence of the revolutionary pamphlets? Or, was a specific object (manual, booklet) that inspired the series?

It was more an understanding, curiosity, frustration with whom and what is allowed or denied within the space of publication, currently and in the past. There are of course many inspiring publications that influenced us in general, we return to or discover in our research.

For example, in the vein of politically driven publications, the work of the Palestinian publishing house Dar Al Fata Al Arabi (1974–1994), which was in itself a manifesto on the availability, form and content of children’s books, created, authored and illustrated by arab intellectuals with a strong affinity and commitment to the Palestinian, Arab and international calls for freedom and self-determination. Their writers and illustrators, who also worked across several publications we read growing up in the Arab world, were essential to our appreciation of book making (content, meaning, function, image, and print qualities).

Dar Al Fata produced square pocket editions that have disappeared from our libraries because of their size, and because they were read to pieces, lent, scribbled on, and also because, perhaps like many, we have moved from city to city, if not across several houses in the same city.

Another inspiring publishing movement was the Master Movement in Egypt (1960s–70s), which was a movement founded by many poets and writers to essentially break out from the Ministry of Culture’s tight control over who and what is published in Egypt. They started many independent magazines, books of poetry and short-stories, forging new ways of writing, outside the established and condoned, as well as printing and (hand) circulating their work. Microsoft Word, home printers and other cheap printing technologies were informing the form and aesthetics of how books are put together. In this book, Ali Hussein Al-Adawy traces the history of some of the figures and publications of this ephemeral and little known movement in the book coming out with the How to maneuver exhibition at Warehouse 421.

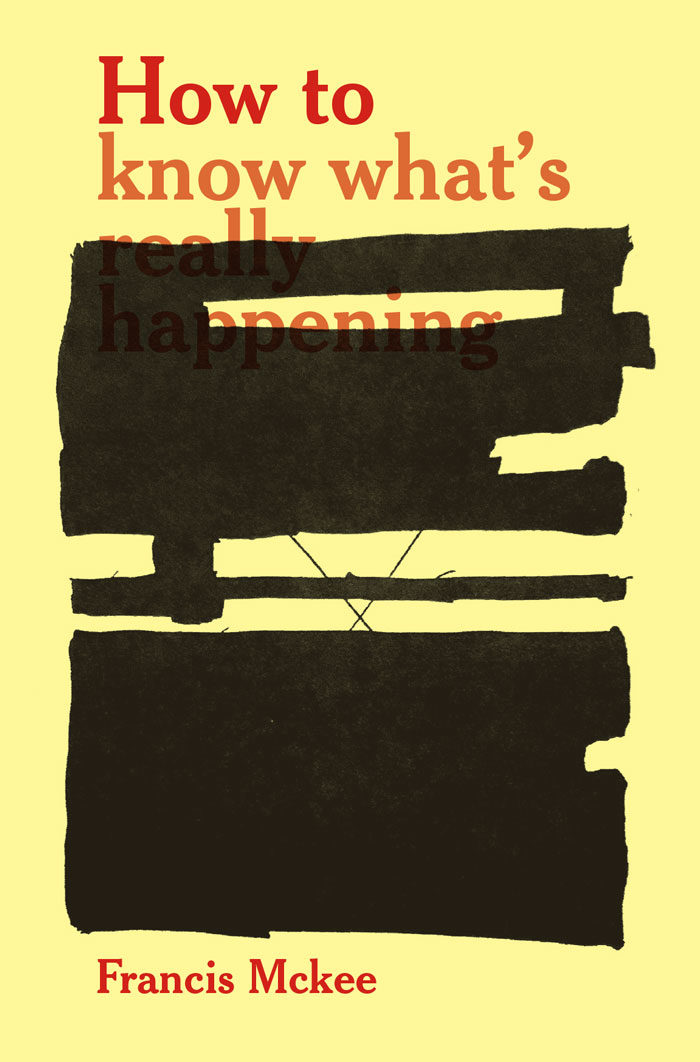

Ali Eyal, No Part Of This Book May Be Reproduced. Texts by Batoul Hammoud. Drawings by Ali Eyal, 2019. Installation shot from How to reappear. Courtesy of Beirut Art Center (BAC).

And the exhibition How to Reappear what kind of instructions does it give? The expression Quivering Leaves of the subtitle, what kind of precarity does it refer to?

How to reappear: Through the quivering leaves of independent publishing was the title of our first exhibition on publishing gestures and tactics. It opened at Beirut Art Center (BAC), Beirut in July, 2019, and another spin on it at MMAG Foundation, Amman in January 2020. The second chapter of this exhibition project is titled How to maneuver: Shape-shifting texts and other publishing tactics, and opened at Warehouse421, Abu Dhabi in December, 2019.

As gleaned from our titles, a central theme running through our research and exhibition projects is the precarity of independent publishing and the survival tactics that this entails. Our first-hand experience of this condition of precarity, relentless yet largely invisible and unacknowledged efforts of independent publishing, as well as the limited understanding of the immense constraints weighing down these slow, low-key and often ephemeral alternative publications, informed our exhibitions and their titles. Hence, the quivering, (re)appearance, shape-shifting, and other maneuvers in our titles.

The exhibition unfolds around “publishing as an art practice” yet another important aspect of it seems to be the right to publish?

Yes, the right to publish, the right to access a public, and to engage in the shaping of our shared public space, bringing into question the visible and invisible constraints defining what and who is denied access to this space, why and on what terms. These questions are some of the fundamental questions that inspire independent publishing.

There are some old works from the 40s and a selection of a designer from the 60s. What is the lineage and the heritage of those practices?

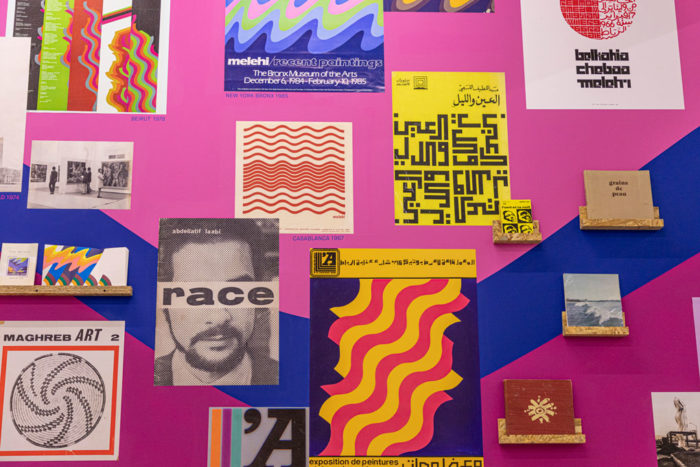

You are referring to two of the projects presented in How to reappear. First, the 1940’s Egyptian magazine Al Tatawur (Evolution), founded by the influential Egyptian surrealist Art and Liberty group. Secondly, the work of the influential Morroccan artist, editor and graphic designer Mohamed Melehi, presented in our exhibition through the research and curatorial project of Morad Montazami, of Zaman Books & Curating. Melehi was also a cultural activist with strong allegiance to the global anti-colonial and Leftist movements. His work includes creating the iconic design of the avantgarde journal Souffles (1969-1966), as well as founding and directing the journal Intégral (1977-1972). Both Al Tatawur and Melehi’s work were inspiring to us in the different ways they pushed the aesthetic, literary and political limits of their time.

ZAMAN Books & Curating. Mohamed Melehi Design Studio 1985–1965., 2019. Installation shot from How to reappear. Courtesy of Beirut Art Center (BAC).

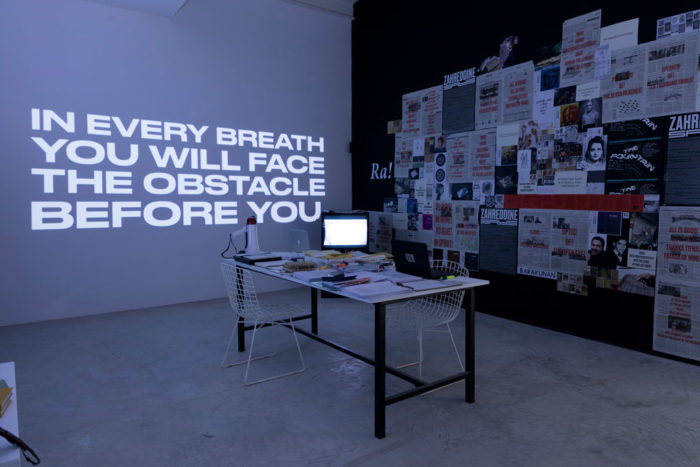

BARAKUNAN Narrative Liberation Front – Bunker 001, 2019. Installation shot from How to reappear. Courtesy of Beirut Art Center (BAC).

In these shows we see the limits between publishable and unpublishable, visibility vs invisibility, isbn vs no isbn, for instance in Bernhard Cella or Omar Zakaria’s work. Could you expand a bit on that? For instance, we loved the anonymous work with the hand-drawn covers. Again it touches the precarious limit between the private and public life of the reader…

Some works in the exhibition focus on the moment, language, practice of exclusion/inclusion, ISBN or no, censored or not, etc. Some projects approach this subject in an expansive way, while others choose to focus on a particular moment or practice. For example, Bernhard Cella did a new call, ten years after his first one, for publications that do not carry an ISBN. This time the call was for publications coming from the Arab world. Through these publications, you get an understanding of what publications chose or had to come out outside the established systems of publishing and distribution. This is a wide array of publications that give an idea of the range of formats, languages, authors, audiences and publishing strategies that exist in the “margin” in this expanded geography. While in his seminal book, NO-ISBN, 1st published in 2015, he explores a rich variety of self-publishing practices from across the world, which we are happy to be translating into Arabic and co-publishing it within the framework of How to maneuver.

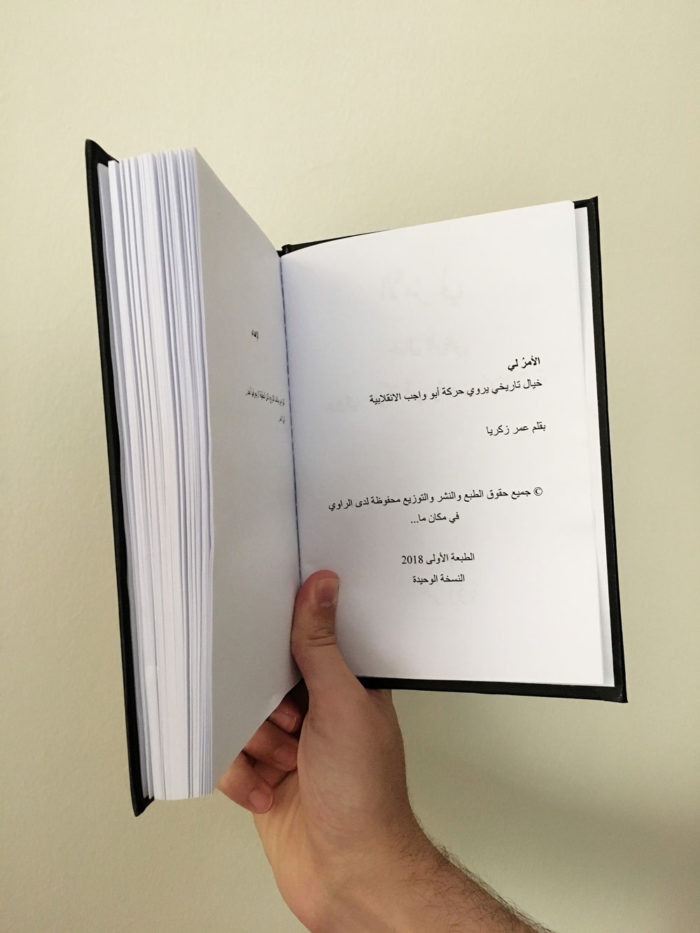

Whereas the work of Omar Zakaria is presented in a single photograph. Omar had written a book some years ago in which he recounts, mixing fact and fiction, a historical event that occurred in Lebanon in 1975. After two years of work, and as he embarked on sharing it with publishing houses, his family expressed their categorical refusal to publish the contents of the book because of their implication in the historical events in the text. The book did not reach any publisher in the end, but Zakaria printed a unique copy. He considers the copy of the book to be personal and only allowed us to show a photograph of it in the exhibition, under the title The decision is mine.

Omar Zakaria. Al-‘Amru Li (The Decision is Mine), photograph, 2019.

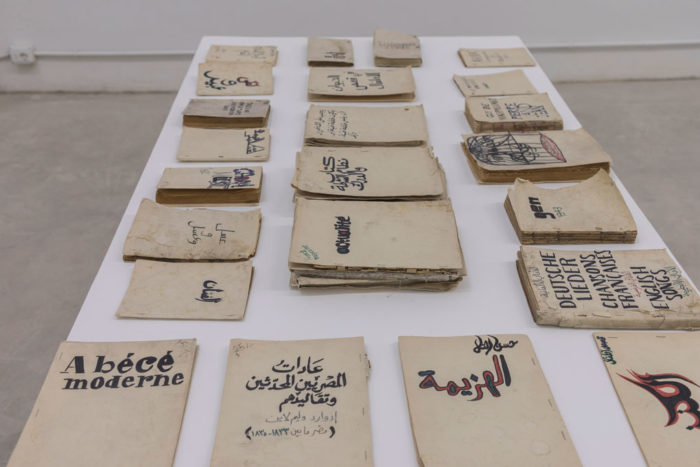

As for the work No longer missing, it’s a selection of selection of books that a title that we bought from Amman, from a bookstore owner who wished to remain Anonymous. Anonymous makes covers for books that he finds without a cover. He looks into what the original cover design, typography and so on were or could be, and makes a simple, hand-drawn book jacket for these books that he then offers for sale in his bookshop, in pay-as-you-wish prices. Anonymous is highly invested in the social and cultural value of books, and the importance of facilitating their access to the reader. He does not consider himself an artist, nor his practice an art practice. But as we were sharing this selection of books in an art exhibition, we had to follow some exhibition codes of presentation. So even though we kept his identity Anonymous, we had to come up with a title for “the work.” We titled it “No longer missing.”

The precarious limit that you referred to, in connection with this work, between the public and private life of the reader is very interesting. Another dimension to this that we have come to learn through our publishing experience is the private readers’ public role as publishers. Our desire as publishers for independence (from commercial market, legal or institutional bindings, etc) is challenged in the happy occasions when our readership becomes larger than our independent means to make the books available. Readers become publishers as their demands for the availability, timing, distribution map, and pricing increase. When titles are not readily available, or are sold out, readers mount pressure on publishers, who are then seen as creators of scarcity, and choose to publish new editions of these titles, through for example scanning and sharing online. It was interesting for us to experience this dynamic as publishers, after experiencing and enjoying it for so long as readers. We actually thought once of how to leak our book to pirates—not the digital one, rather the ones who scan, print and sell pirated copies in the market. We thought it wouldn’t actually be that bad, since we are a non-profit in any case, if they would bare the cost of production and help us distribute these titles far wider we ever could on our own. The catch though is that our books are sold cheap in the local market, and so are not such a lucrative investment for pirates… But anyways, the private/public life of the reader is indeed a curious topic.

Anonymous. No Longer Missing. Publications, n.d. Installation shot from How to reappear. Courtesy of Beirut Art Center (BAC).

Also the shows somehow made me think of James Langdon’s Book Show or Charlotte Cheetam’s Open Books, but in a very different geopolitical context and mood, as if you guys would have re-read Carrion more from a poet’s point of view (rather than from a designer’s), which is somehow philological…

We feel our shows develop from our cumulative experiences as artists, readers, indie publishers and curators, and in response to our local concerns and contexts, which naturally are not separate from the global contexts that affect and are affected by them. Nor as you say is the poetic separate from the practical.

Beside the selection of publishing practices there is a rich selection of artists’ books. Which one of these formats cannot exist otherwise? Why is the distinction necessary, intrinsic or specific?

The works shared in the show come from projects that come from within or outside the realms of art. Both formats were brought into the exhibition without any separation between them. They come out of separate yet often related concerns with context, dominant artistic, publishing environments, and distribution. We did not stress on the distinction but rather wished to understand how they were created, their production contexts and languages shared in both. Their varying weight that they give to form, function and accessibility is interesting to see and understand, each on their own terms but also in relation to each other.

Bouchra Khalili. The Typographer. Video (b/w), 30’3”, silent, 2019 and The Radical Ally. Publication, 2019. Installation shot from How to reappear. Courtesy of Beirut Art Center (BAC).

Bouchra Khalili’s works got us to think about the deep correlation of publishing and resistance/revolution. How does these shows tell the story “not speaking for, not speaking on behalf nor in-lieu of, but from the position of the witness”?

You can say that the act of independent publishing is, in and of itself, an act of resistance against dominant norms and tendencies in publishing. These publishing tendencies are not just pragmatic tendencies, shaped by economies of production, distribution and profit, but are also political, reflecting and affirming dominant politics over less fortunate subjects and subjectivities.

Bouchra revisits in her work The radical ally, Jean Genet’s conception of allyship: “not speaking for, not speaking on behalf nor in-lieu of, but from the position of the witness.” We find this subject both interesting and important, in exploring the contemporary moment and the specificity of our contexts, but also the histories and lineages that run through publishing/resistance practices disparate in time and place.

As publishers, we see ourselves as part of an expanded realm of independent publishing, that has been and continues to be challenged in different ways. And so, in addition to sharing work with the public, we try in these exhibitions to work towards the creation of networks or “alliances”, in both the poetic and practical senses, that would help enable and facilitate our individual and collective practices. For example, as artists and or indie publishers, we share similar experiences and challenges. Distribution, for instance, is an old and ever problem. Through the conversations we had in the first edition of this show, How to reappear (at BAC, Beirut), we decided to focus on distribution in a symposium held within the program of our 2nd exhibition, How to maneuver (at Warehouse421, Abu Dhabi). The invited speakers include publishers, independent or not, distributors and other practitioners in the field whom we believe are relevant to our specific concerns, and can engage with us in a useful conversation.

How does publishing become record, distribution, network, ephemera, archive of revolutionary practices?

Here are some reflections from the works in the exhibition. When we invited Ali Eyal to respond to the topic of independent publishing, he chose to return to two things: Baghdad’s Al Mutanabi street, once the Arab world’s largest book market, and to his mother’s notes that he remembers her scribbling in the empty pages left for readers in an Iraqi magazine called Aleph-Ba (A-B.) He finds her personal notes and diaries in her parents’ house in the south of Iraq, and considers the act of physically relocating these “emotional texts,” akin to publishing them for the first time. He “published” them, not through a book but through the “Blue Luggage Publishing House,” which he found near the bedroom on the second floor.

These notes were mostly written in the early 1990s, when the US war and sanctions on Iraq were affecting Iraqi lives and livelihoods. Ali Yass, another artist from Baghdad, now based in Berlin, produced a work on the US army leaflets dropped on Baghdad during the first days of the American invasion of Iraq in 2003. Yass still remembers not only the huge sand storm that delayed the advancement of the US troops, but also how he hoped for rainfall to clear the dust from the air, only to see it raining, so many leaflets. He calls his project Rainy Days, after a poem by Badr Shakir Al Sayyab, who in the 1960s “shape-shifted” classical poetry structures and revolutionized the poetic and political writing of the time.

Al Sayyab is seen in a hand-illustrated mural by Ferhas Publishing Practices that they presented in How to Maneuver. He is one of the figures appearing in Fehras’ elaborate and eye-opening map of cultural and political relations in the Arab World during the Cold War era, which as they describe was “among the most fertile and critical periods in the history of Arab culture and publishing because it entangled and intertwined politics with culture. World War II had drawn to an end, some Arab countries had achieved independence, and new Arab regimes had seized power. These changes aligned sharply with a range of ideologies—communism and Marxism, leftist liberalism, Syrian or Arab nationalism, Nasserism and Baathism—that indelibly marked Arab culture and publishing.”

As for Kayfa ta, it’s been a very inspiring trajectory working on these series of exhibitions and publishing projects, encountering the vast as well as the minute gesture, the isolated and the networked, the quiet and the loud. We are happy to continue following the different threads of research and collaborative work through future exhibitions and publications. This book in your hand has been developed within the context of the How to maneuver exhibition. During the process, we thought it would be better to take it out of the closed format of an “exhibition catalog” to a more open, collective and on-going format. And so, this book is the first in a new series of how-to books called kayfa tanshur, or How to publish, through which we would like to continue our collective research in the rich publishing practices that run through our various practices, institutions and cities.

This interview will appear on a publication produced within the context of the exhibition How to maneuver: Shape-shifting texts and other publishing tactics at Warehouse421, that will be launched on 8 February 2020 at Warehouse421, Abu Dhabi. The book is the first of a new series of publications by Kayfa ta called How to publish, in Arabic and English editions.