Turning Nation into Nature

Renato Leotta and the final impulse of the industrial economy

Bvlgari Prize nominee Renato Leotta’s work Sun distills some of the most pressing issues relating to Italian identity today. His practice has been predominantly concerned with recording natural phenomena, while challenging the traditional use of supports as marble, canvas and photographic paper. This new work speaks about Piedmont’s industrial history, and activates a critique of institutions, regionalism, canonical display and engrained colonial attitudes. Originally made for the Piedmont Pavilion in Venice during the last Art Biennale, Sun is currently installed at Castello di Rivoli in the artist’s first solo exhibition in an Italian public museum.

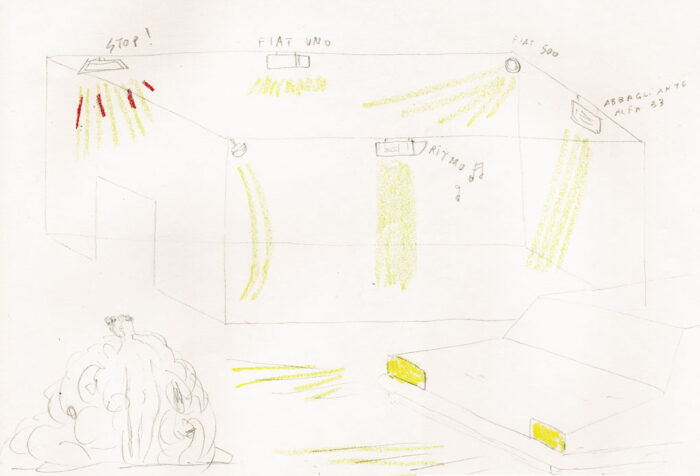

Sun is an installation made of iconic Fiat cars’ headlights from the 70s, 80s and 90s that replace the conventional lighting system of the museum or gallery. Wired as high beams, they project potent rays across the exhibition space and can be easily mistaken for sunlight. The work was first shown at the Piedmont Pavilion, an initiative of Castello di Rivoli and Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, who controversially presented themselves as a nation within the nation, mounting this collateral event at the 2019 Venice Biennale. On this occasion, Leotta made Sun with the aim of bringing forth unexpected connections between the artworks on show (a heterogeneous range including works by Lara Favaretto, Carol Rama, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Irene Dionisio, Ludovica Carbotta). In the new exhibition at Rivoli, the artist decided instead to highlight baroque details of the historic savoy castle that now houses the museum. His objective in doing so, was to examine “the final impulse of an industrial economy that left its spaces to the culture industry.” In fact, the architecture of Piedmont’s industry, led by the car manufacturer Fiat, has been taken over by the culture industry, which now occupies both its former royal households—such as the Castello di Rivoli—and its industrial spaces. Amongst these are the Lingotto, a former Fiat factory that now houses museums and fairs including Artissima; the Officine Grandi Riparazioni (OGR), originally an industrial complex dedicated to repairing trains now turned into cultural venue; the Fondazione Merz housed at the former Officine Lancia power station. Leotta’s interest lies in recording the traces left by former regimes—whether monarchic or industrial—on the current cultural landscape. The work brings to the viewers’ attention architectural details readily associated with the region’s baroque tradition. In this way, the museum’s press release reads, Leotta “illuminates, with subtle humour, all that is Piedmontese in the building.” Further still, by focusing on two of its distinctive attributes—the industrial and the baroque—the work distills the region’s identity, where, Leotta concedes, “the universality of nature is lost.”

Over the phone and in our correspondence, the artist explained further some of the concerns behind his work. Amongst the most pressing, are issues relating to regionalism and nationalism and nature’s role within the definition of identity. Belonging has been a leitmotif in his practice, which reflects his own fractured heritage between Piedmont, where he was born, and Sicily where he grew up: two regions that inevitably localize him geopolitically. An enquiry into the meaning of Sicilianity is evident in the memorable work presented at Manifesta 12 in Palermo at Palazzo Butera, titled La Notte di San Lorenzo (The Night of Saint Lorenzo, 2017). Here, Leotta chose lemons, a typically Sicilian product, as a symbol of “the intrinsic productivity of the earth, beyond any kind of regionalism.” The work consists of a terracotta flooring (also a quintessentially Sicilian medium), made of tiles furrowed by the marks of fallen ripe lemons when still unfired. The work’s title adds a further poetic dimension by invoking the homonymous yearly appointment Italians have with shooting stars on August 10th. With this work, Leotta brings together Italian traditions, its earth and fruit to present the portrait of a region, which has much more to do with nature than with any reference to nationalism or politics (persistent in the debate around Italy’s North/South divide).

Speaking of this work Leotta explained: “I like to think about the relationship between Palazzos and land. In this work I recreated the exact perimeter of a room in Palazzo Butera within a citrus fruit garden, located in a hypothetical productive fief. The point is that the Palazzo and its fineries in the middle of the city subsists thanks to the productivity of the countryside (to subsequently become a tassel in the cultural economy—as is the case of Palazzo Butera, a former mansion turned into an exhibition venue)… As you point out, nature is at the centre, and it is tangible through universal laws such as gravity. Fruit falls to the ground when it’s too ripe, or excessively heavy, because it is attracted by the core of the earth we inhabit. I also like to think about the garden as a starry sky (also reflecting on the observation of celestial bodies first archaic and then Greek—perhaps the true identitarian matrix of the island)… In my reflection on the sky, I selected citrus fruits, specifically lemons, for their spherical shape, which recalls the shape of the planets in the cosmos in a sort of mirroring between earth and sky.”

In order to probe the ways in which the cosmos and invisible natural forces become manifest on our planet, Leotta has relied on chemistry. In measuring natural things such as the intensity of moon, sunlight, heat, the density of salt, the movement of fireflies, references to belonging remain ubiquitous. In the iconic series Alla Patria (To the Homeland), Leotta layers one side of perfectly rectangular marble prisms with a cyanotype, a chemical agent sensitive to the intensity of UV rays used since the earliest experiments in photography. The time during which the works are exposed to sunlight—a whole day or an afternoon—determine the intensity of the cyan hue on the chemically treated surface. The result is a live sculpture/photograph that continues to change until Leotta interrupts the chemical reaction. Especially because of the title of the work, which is a dedication to the Homeland, the tension between nature and nation is once again a determining element in its interpretation. The work offers empirical evidence of the intensity of sunlight, while suggesting that the specific sunlight captured by the work is unique to a homeland. Throughout his practice Leotta erodes the geo-political connotation of a homeland turning progressively towards a definition of belonging through nature.

When I asked about the connection to nature in Sun, the mechanical and quintessentially Piedmontese work at Rivoli, Leotta explained, “…whether working in Sicily, Turin or London, there is a scale of conventions that are more or less in tune with their surrounding landscape.” He continued telling how each territory corresponds to an attitude and a set of codes of signification that form independently of canons and conventions. The Sicilian landscape informs a different kind of display compared to the one in Piedmont—where even the sun turns into a machine.

Leotta will formalize his enquiry into modes of display in a forthcoming project at the Castello Ursino in Catania. There, alongside researchers Pietro Scammacca and Claudio Gulli, he will be exhibiting artifacts from the eclectic collection amassed by the V Prince of Biscari, a noted archaeologist of the Baroque period. “We are imagining a museographic display that will have a structure inspired by the solar system that will avoid conventions and temporal or geographic paradigms (of domination)”—Leotta advanced. The artist’s efforts to think critically about modes of display, regionalism and territorial identity, resonates within the politics of Italian culture today. Currently, Italy boasts over 80,000 public museums which the Ministry of Culture and Tourism (MiBACT) coordinates with titanic efforts. Due to limited funding or ill-management, public museums are often partially closed, inaccessible, are unable to properly conserve their artifacts, among innumerable other issues. The state of Italy’s historical heritage is often a cause of frustration. Leotta recalls some joke made by foreign tourists about ‘Italians’ when seeing rooms closed off in an archaeological museum. Taking a cue from Leotta’s projects, what would happen if higher consideration was given to the peculiarities of the landscape instead of (often imported) canons of curatorial practice or display? Is it imaginable to install and display cultural heritage in a way that is more aligned to the territory, while fostering collaborations with contemporary artists?

When closing our conversation, after discussing the challenges faced by the Italian cultural heritage, Leotta voiced his concern with what he named the “colonial character” or “paradigms of domination” that oftentimes inform the dynamics through which culture operates. This is not only evident in the way art is displayed—as in, responding to fixed canons and conventions that are often non-aligned with their territory. It also appears in the ways objects are classified and valued, according to strict hierarchies that, for example, divide art from craft, archaeological artifact from mirabilia. Leotta further outlined in relation to a work that will soon be exhibited at MAXXI in Rome: “The footage I’ve been shooting for the last year addresses the relationship between North and South, and their relationship with myth-making. Here archaeology comes into play again. I’ll give you an example: the docking points of the first settlers and proto-colonizers of Magna Grecia are the same docking points of the petrochemical industry (Thapsos, Megara Hyblea, Hymera, Taranto, Gela and so on)—a dramatic issue both in terms of environmentalism and cultural deprivation. I am very interested in thinking about myth-making and the colonial continuity of these fertile and productive areas.”

By examining in such terms how forms of colonialism exist within the cradle of Western civilization, radical possibilities may open up for challenging the persistent colonial attitudes that characterize Western culture. Over the coming months, we’ll be able to see how Leotta’s research progresses in Cuneo at the medieval Complesso Monumentale di San Francesco, where Castello di Rivoli and Fondazione CRC are launching the exhibition E Luce Fu (Let there be Light), featuring Leotta’s Sun alongside two additional pieces by Olaffur Eliasson and Giacomo Balla. This October, MAXXI in Rome will host the exhibition for the 2020 Bvulgari Prize featuring some new work by the artist.