Troubling of a Star

A conversation with Emily Jacir and Michael Rakowitz

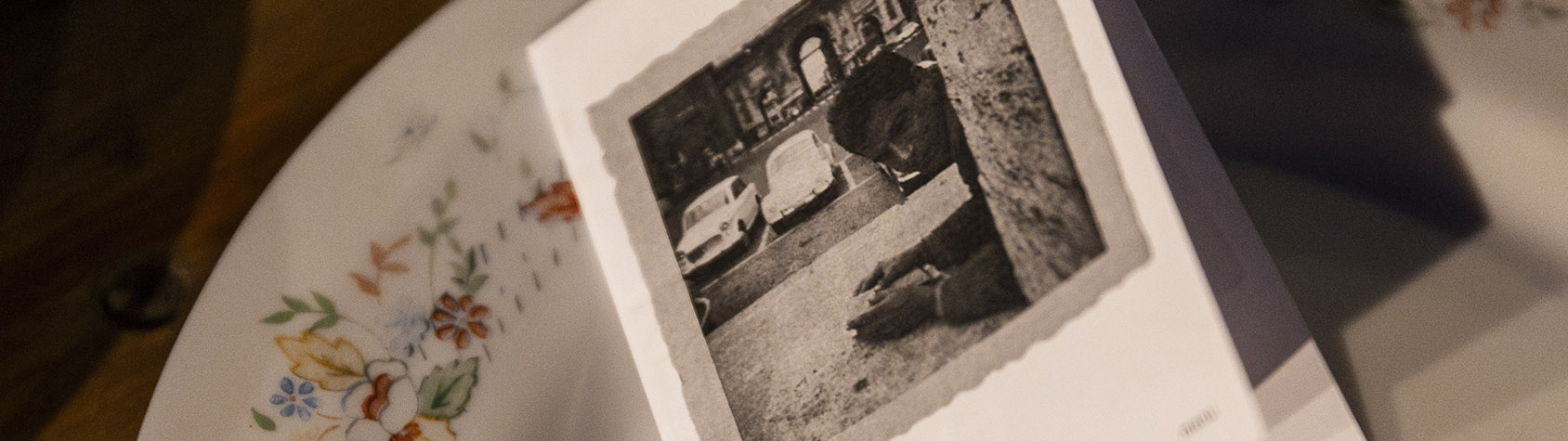

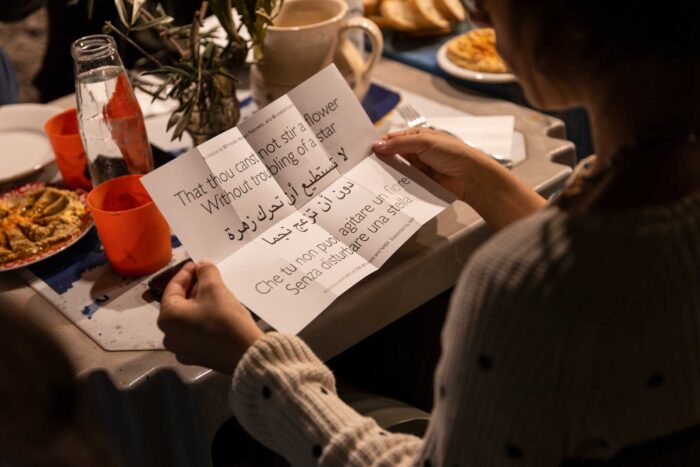

As a conclusion of If Body 2024, Palestinian artist Emily Jacir and Iraqi-American artist Michael Rakowitz decided to convene a community in remembrance of Palestinian writer, Wael Zuaiter, assassinated in Rome by Israeli Mossad agents in 1972. While a poster reprinted from Paese Sera designed by Emily Jacir and originating from Material for a Film appeared in the streets of Rome, the two artists organized That thou canst not stir a flower Without troubling of a star, a performative dinner at La Città dell’Utopia in Rome, where guests were invited to share food and stories, weaving together several temporal spheres, made up of memories and poetry.

If Body is a public visual and performing arts program that focuses on the body as an artistic language and learning methodology based on experience and participation. Conceived and curated by Sara Alberani, Marta Federici, and Chiara Siravo (LOCALES), this year’s edition is titled Living Fragments. Through seven events, it presents new performances, talks, workshops and exhibitions that explore the cultural, social, and political meanings associated with the body and corporeality. This edition features interventions by Aliaskar Abarkas, Soukaina Abrour, Adelita Husni Bey, Noor Abed & Lara Khaldi (School of Intrusions), Emily Jacir & Michael Rakowitz.

This conversation happened the day before the event, during the preparation of the meal (imagine the smell and the sound of chopping fresh colorful vegetables).

Giulia Crispiani: The supper is an occasion to remember, to celebrate a recurrence as well as a moment to mourn. How your long-standing collaboration has generated the organization of such an event, and how does this bring your respective practices together?

Michael Rakowitz: When LOCALES invited us, we started to think about how we could naturally respond to this invitation. I was grateful when Emily brought up the idea of doing something around her work, Material For a Film, but also with the title itself “That thou canst not stir a flower Without troubling of a star.”

Material For a Film is an ongoing work, and I have an ongoing practice as well, and a lot of the projects that I do involve food. So we thought, what does it mean to remember Wael at this time? I thought about how we might do something using the natural form of the reception, which is something that exists, of course, when one celebrates an artwork or an exhibition. But I also thought about the fact that when one makes an artwork, it is like putting a signal out into the air, and there is always a hope that somebody receives it. Emily’s work has been quite foundational for the way I think, and our friendship has been that as well—this idea of somebody hearing what you’re saying. I feel like Emily’s work has had this kind of impact on me, me being somebody who has received it. This also applies in thinking about what it means to “receive” Wael, in the context of doing something in remembrance.

Making the food for the project’s reception was something that interested me, and when I work with Iraqi Jewish cuisine, or Iraqi cuisine in general, it is about making present those generations that have come before me and have disappeared, a part of wishing for them to come back. When you remember someone they’re alive again in a way. In the Jewish religion, when somebody passes away we say “May their memory be for a blessing.” It’s not just about blessing the memory, it’s also about remembering them through deeds and acts, so in your life you do things that they might do. That involves thinking about this incredible person that Wael was and who he continues to be. To do things like making hummus with peanut butter, this comes from some of Wael’s recipes that Emily shares through Material for a film. In the 60s, when it wasn’t easy to get tahini in Rome, he had to substitute it. That aspect for me was one of the ways to think about the idea of the supper, to think about what it means to gather at a time like this, in the midst of genocide. It’s important for me to be with Emily. We were together in January here in Rome, as well with our students, and there’s nobody who I would want to be with more, at this time of the year.

Emily Jacir: Being invited to do this project in the middle of a genocide made us think about the fact that we have been in conversation as artists, as friends, and as thinkers for the last 25 years. We were thinking about this even before this invitation, how important those connections are to make visible. As an artist you never make work in a vacuum, you’re always in a conversation. Personally, I was really invested in the idea of working with public space, because I constantly walk around Rome and I am very aware of the conversations happening on the walls of the streets. So for my contribution to this collaboration, I proposed bringing Wael back into the streets of Rome, and to continue to have this both personal and collective dialogue with all the things that are on the walls of this city every day. Michael complemented the street action with a dinner, which is something that also extends out from our past collaborations: the very first workshop we did at Dar Jacir for Art and Research in Bethlehem in 2018, was run a workshop together for a week that culminated in cooking food together with the participants and sharing it with all our neighbors on our street.

What will be on the menu?

Emily Jacir: I went through my archive—my interviews of a lot of the people who knew Wael—and found this one sentence by his friend Enrico, who said that he used to make hummus out of peanut butter. So that is one of the things on the menu, together with Knafe from Nablus, because Wael is originally from Nablus. And…

Michael Rakowitz: We’re making Mhasha, which consists of stuffed vegetables, and it’s a recipe that’s shared by everyone across the region, in Mesopotamia, Palestine, and everywhere else. It is also the food we eat during the new year, and that’s actually something that’s happening right now, as the sun is about to go down. It is supposed to be Yom Kippur, so we’ll be breaking the fast in a way—I’ll be breaking my fast on this Mhasha, which is believed to be a harbinger of good things to come. The idea of stuffing the vegetables means that there’s this hope that the upcoming year is filled with sweet and good things, which is a hard thing to wish for in the midst of a genocide, but here we are together. Mhasha is a big part of the Palestinian cuisine. We are making a vegan version so everyone can enjoy it, and we’re using Baharat, a spice mix that Emily brought me from Bethlehem as a gift. It’s nice to be able to share that and to taste the place where Emily’s from, a really special place. Then, part of the dessert is the Ma’amoul cookies that I smuggled in from the US, one of the only brands with the word Palestine on it—it says “Taste of Palestine”—and there is a certain kind of resistance in that product. In my work I talk a lot about the provenance of ingredients. There are Palestinian dates inside the cookies, so that will be another part of the kind of communion that comes from eating this meal.

To gather and to tell stories, “to honor memory and poetry”—at the moment it is impossible for me not to consider this as a praxis/form/mode that counters fascism in a broader sense, and its hegemonic narrations, already through the richness of flavors, that serve as a base to deconstruct appropriation and extractivism, or?

Emily Jacir: Wael’s life was about poetry. He survived because of poetry. Poetry is inherent to my life, my work, my practice, and I also feel like I can’t survive without poetry. I invited people who knew Wael to come tomorrow night, and invited them to speak to his memory. That is a really important aspect of this project as well. This morning, I shared some of my archive with the students, and with Michael and Sara. It is unbelievable to look at the way things were written, they had exactly the same conversations, exactly the same as we are having today.

In the spiralic time of resistance, I feel we can consider this supper to be for and with Wael—he will be among us, in as much as one flavor can take us back to a place, one struggle contains another, and we rejoin with our losses by means of remembering. What do you expect will happen to time during this reunion?

Michael Rakowitz: I think it becomes timeless, timeless time. I really don’t like words like ancient, because it’s one of the things that severs the objects from their histories, the stories and the actions of the past—without considering the fact that people from that time are descended: everyone’s life is a vector, and we’re just at the tip of the vector. Everyone who came before us is part of that.

I don’t think that it’s fair for Emily and my relationship to be completely framed under the terms of the present. We have been doing this for a long, long time. We’ve had a relationship that should not be exotic to anyone. Our families and we have so many things in common, I am convinced that our grandparents knew one another in some way. This was just very normal.

In the last hundred years, we have witnessed a cataclysm, a rupture that has been an interruption of the way life was, and always was, and the way it can still be. There’s no reason why that interruption can’t be interrupted and time be sutured. We are everyone who came before us and we are living in atrocious absurdity. The time that is being put forward in the spaces that we create, is the right time. This is a time that is joyous for us, a time that is generative. Every time we meet up, I feel like I get more ideas, I feel more alive, and that also comes with communing, with who Wael was in his life. I’m a huge Beatles fan, and when I saw Emily’s work, Material for a Film, and heard the guitar recording of Yesterday, it was so moving to me, I felt like Wael was someone who I already had fallen in love with, through her work, and I said to myself, this is somebody we would have hung out with. This creates intimacies across these divides: I might not have lived during the time that he lived, but I am living at a time in which Emily brought him to us.

Emily Jacir: I would also add that I’ve always seen the work I did on Wael as a collaboration with Elio Petri and Ugo Pirro, who were going to make a film about him, until Petri unfortunately got very ill and passed away. Their original notes are what inspired Material for a Film and I have always seen this as a collaboration across time— time collapses in that sense between Wael, them, me and Janet (Venn-Brown) and people who will pick up where I left off in the future. It is a collaboration that cannot be contained only in a present time in a way, it is the exchanges of a network operating across time.

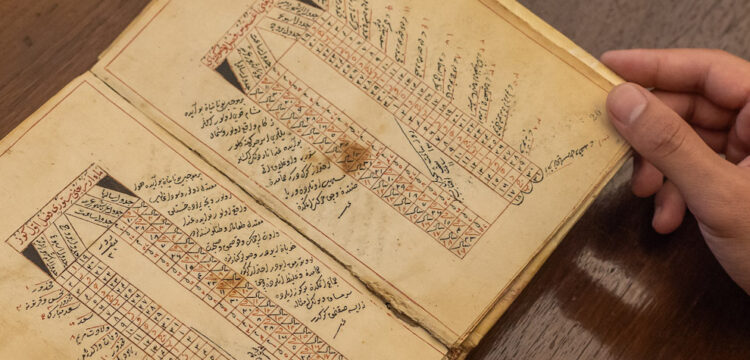

Wael Zuatier was meant to translate One Thousand and One Nights into Italian. This brought me to think about translation, and how we convey complex experiences like violence, which is so layered across time and space, and how every detail becomes as relevant as a multi-voiced witness. Why is it worth remembering what happened to Wael Zuaiter now?

Emily Jacir: What’s really interesting about what you bring up is that his project was to translate One Thousand and One Nights, and it got ruptured by the 1967 war and the occupation of the West Bank by Israel. That project, which was his passion and his life’s work, had to be put to the side because of the immediacy of his family being under military occupation. He was a pioneer, and it is important to honor him as such. He had to translate the political situation into Italian. He was intent on meeting Italian filmmakers, intellectuals, poets, and writers to tell our story, and narrate what was happening. He brought Moravia to the Arab world for the first time. It is interesting, in that sense, to reflect on that now, in this moment, because it is another rupture.

In the first iteration of Material for a Film, I focused on the bullet that went through the copy of One Thousand and One Nights that Wael had with him the night he was assassinated. I was thinking a lot about translation in that first iteration, about stories which can’t be translated. Now we are in a completely different moment because this genocide is being livestreamed. I don’t have the space or the capacity to comment on that right now because it is beyond horrifying and shocking. People are just going to keep watching us be slaughtered in the most disgusting, brutal, horrific ways you can possibly imagine. And nobody is going to do anything to stop it.

“That thou canst not stir a flower, Without troubling of a star”—why did you choose this fragment?

Emily Jacir: This quote from Francis Thompson was included in the last article Wael wrote for L’Espresso, before he was assassinated. All of his friends told him ‘you can’t put poetry in a political article,’ But he did, and he insisted on it. In the original iteration of my installation, Material for a Film, that quote closes the final shot of the movie, and it’s really important to me.

When Michael and I were talking about the project, we reflected on what happened to Wael, and on how that moment reverberates across time, and in and out of all of our lives, in our networks, and in all the work we do.

Michael Rakowitz: Absolutely. I agree. It is important not to crowd the poetry with too many other words. Like all great poetry, it has something that feels so specific and at the same time so confounding, like a riddle. And I think about how we have been so devoted to poetry, even in the midst of struggle.

Emily Jacir: I can’t survive every war and every bombing without poetry.

Michael Rakowitz: War is a space where language ceases to function. Art is another one of those spaces. I far prefer art and poetry. Art succeeds where language fails. Language that’s used by poets is something that isn’t considered to be simply conversational, everyday language. Something about it invokes a certain kind of stoicism, and you give all those words extra attention because everything else around it is so spare. That for me is one of the reasons why art remains so important in these catastrophic moments, it’s like the lifeblood of survival; it reminds us of who we are as humans that are able to make such things, even while we are constantly destroying and being destroyed.

Emily Jacir: Another thing is that Wael’s project in Rome was also a project of co-resistance, allyship, and friendship with the Jewish community. If you look at all the people he worked with, all of his friends and the quotes, everything, the people who were most shocked at his assassination were his friends from the Jewish community. They couldn’t believe that someone who was a pacifist and who genuinely worked toward reconciliation, would have been the one targeted. The silencing of that narrative has only intensified today—something that Michael and I have been discussing for 25 years. It feels as though the actual real friendships and solidarity between us all is constantly being erased.

(Living Fragments is the title of this edition of If Body) Can we say that this is a work of fragments and that they are all living? What is their value?

Michael Rakowitz: When it comes to fragments, I just think that we are broken before we even get here. Poetry is powerful in its ability to allude to more than itself. The language that you see in a poem is also alluding to the space around it and the stuff that it may have been detached from or is trying to connect to.

In many ways, I feel like I fit with Emily. We come from different places, but there’s like a contour of our lives that lines up, and we could glue us together right there. Fragments can sometimes be fetishized, locked into a vitrine where they can never be completed again. But it’s important to understand that it’s not always about being “made whole”. You can still live even without being “made whole”. The broken contours must remain visible.

When we talk about If Body, in that essay Lauren Berlant talks about a drawing or a painting by Riva Lehrer, who I actually know very well from Chicago. Her work reveals so much about seeing the world through the lens of disability. There is an expectation that people with disabilities should be made whole, but for what reason? So we can feel more comfortable, so that able people can feel more comfortable? It is an open question for me.

Fragments are alive, I don’t think they ever aren’t, they can be sutured to other things, permanently or temporarily. However, those fragments don’t necessarily require something extraordinary to make them alive. I think of the phrase “Thou canst not stir a flower, Without troubling of a star”. It seems like it is part of something bigger, but those words, on their own, already do something. With poetry one can breathe life into the words.

Emily Jacir: For me, it is the space between fragments where I operate. This space is the body—the body brings fragments together: through itself, but also through time, networks and exchanges.

The night after we put Wael’s poster and the date of his death in the streets of Rome, and I received an email from an Italian-Palestinian fashion designer I had never met before. He wrote to me saying “I saw Wael on my street. I didn’t know who did it but I knew you made a work about him so I wanted to share these photos with you. At first I didn’t know who it was, but my father was his friend and he told me.” This is the physical body, the physical poster we put on the wall, the physical exchange that’s happening with bodies in space, gathering together. This is the body to me.

I would really like to acknowledge something very important. Rome and Italy have been so integral to my work as an artist, thinker, and activist. I have never been in any exhibition in this city. This is the first time that I have been able to do anything with my work on Wael Zuaiter in Rome. Material for a Film (2007) is a work that won many awards, including a Golden Lion in Venice. And yet no one in Rome—the city that this piece is about and the city that has impacted me so much as an artist, has ever considered sharing this work. LOCALES is a pioneer on this and I feel that’s a really important point to reflect on. It makes me think a lot about precarious spaces like theirs and working in precarious ways. These precarious spaces are where these kinds of conversations are happening.