Translocal Cities

A walk through Manifesta 15

We are constantly located and immersed somewhere, either loving the place we are in or thinking we should move somewhere else, travel abroad, or go out for the weekend. We are continuously side by side with the thought of the city or the country we are in, whether it be in words (“London traffic is impossible. I’ll take the tube”), in conversational or informal discussions with other people, by evidence in, for example, the ever-present shops’ signs or other indications on the streets (“Berlin Deli Delight”), in pins on our Instagram posts and stories. I often find myself speculating about the enormous impact cities have on our daily lives and especially on the way we relate to the arts. Cities do play a pivotal role in the amount, frequency, and especially quality of culture we are exposed to.

The cultural planning of urban cities is something that has come to the foreground of the social and political agenda at the end of the 1990s, particularly so within many European Union cities when the surging and peaking effects of globalisation, including to a certain extent a unifying homogenisation in material and non-material culture, started to spread almost in every European capital. In this sense, cultural policies and planning as promoted by cities, metropolitan cities, municipalities, counties, or even regions, came to represent a negotiation site of different vectors of local and global identity, a transforming and transient place of transaction where processes of local reevaluation (of places, immaterial histories, customs etc. and, more than else, a local and cultural art scene of professionals and operators) entered in dialogue or in contrast with international crowds.

The art biennial Manifesta was born at the intersection of the Maastricht agreement, a progressive interest on behalf of regions and cities to affirm their presence on the map, and neoliberalism. It is an expression of a Pan-European world in the making, in the midst of a hyperconnected, globetrotting scenario, emanating from the offices of the Netherlands Government Culture departments. Manifesta committed itself to discovering and sewing the neo-sutured division between the West and the East. Right from its inception, Manifesta, was born as an essentially city-bonded and urban-scale conceived event, itinerant in its passage, recurring every two years, and devoted to young, emergent artists.

Its first edition opened in Rotterdam in 1996, five years after it had originally formed as a foundation. It then travelled to Luxembourg, Ljubljana, and Frankfurt, crossing the East/West border with its third edition in 2000. Through a complex and initially mixed system of funding, Manifesta declared itself as an heir to the Young Artists Biennial in Paris and in fine-tuning with documenta’s political remit. [1] As such, almost from its inception, Manifesta has soon looked into idiosyncratic regional contexts, simultaneously shifting the discourse from an East-West to a South-North axis, introducing this movement with its fifth edition in 2004 in San Sebastián, entering Spain for the first time.

Mainly sticking to the European Union––with an exception in 2014 with Saint Petersburg, in the edition entirely entrusted to the curatorship of Kasper König––it thus traversed the Basque Countries, Northern Italy and the Autonomous Region of Trento in 2008, came back to Spain in Murcia in 2010, Belgium with Ghent in 2012, then to Russia, Zurich in 2016, Palermo in 2018, and Marseille. Challenging borders, the biennial saw its sixth edition in 2006 cancelled in Nicosia, in the still divided island of Cyprus, and was successfully delivered in Kosovo in its 2022 edition in Pristina. In any case, whether it be the case of Spain, autonomous regions, newly European regions, or cities operating in the economic earth of Europe, the biennial has always kept the city and its urban dimension at the centre of the stage.

In its fifteenth Edition in Barcelona, Manifesta has introduced a renewed format embracing an unprecedented regional extension. This year’s choice by Manifesta of the city of Barcelona surely is, in part, motivated by the ambitious city’s bid––in discursive and economic terms. [2] On the other hand, the bid encounters a challenge posed to many European cities today, meaning phenomena of massive gentrification, mass-touristification, and inaccessible rental costs, which interfere with residents’ life quality and that Barcelona experiences on a large scale.

I cannot help but think “I am in Naples ” where I am currently based while writing this essay, every time I go back home from the place where I work, in the city centre’s gut, between via Duomo and Spaccanapoli, walking through via dei Tribunali, all the way across the San Domenico square, Santa Chiara, Monteoliveto, and via Toledo, being terribly pissed off at tourists I must make my way through. Often, too often, I find myself apostrophizing these tourists, as if they were one giant collective body moving headlessly, as enchanted zombies hypnotised by the disturbing smell of some fried food and the cheap bling-bling of poor-quality souvenirs my mother loves to put on her fridge—alas.

Thinking about European cities today, I cannot help but notice how many of them share the same fate, dealing with similar issues that created their global lure. There is, however, some degree of sadness in seeing how many bars and hipster shops (with some delay) are today filling Palermo’s streets––especially since 2018, when Manifesta 12 passed through or watching high-in-carbs tourists hypnotised by the promise of € 3 spritz and shoddy pizza in Naples. Arguably, Barcelona’s streets must look the same to its residents as they did when visiting this year’s Manifesta, realising its fate is not so different from that of London, Paris, and Berlin.

Manifesta has acted as a sort of thermometer of the European Union’s transformation, reflecting Europe’s issues of the day from the 1990s and the 2000s to the present day. Today, Europe’s most compelling issues (still) are its closed borders and inaccessible rights (which Manifesta 12 in Palermo, for example, addressed). By paradox, seen from the inside, the other might be considered that of its cities’ hardship, with their excessive tourism, property speculations, warping gentrification, and overarching pollution.

Manifesta 15

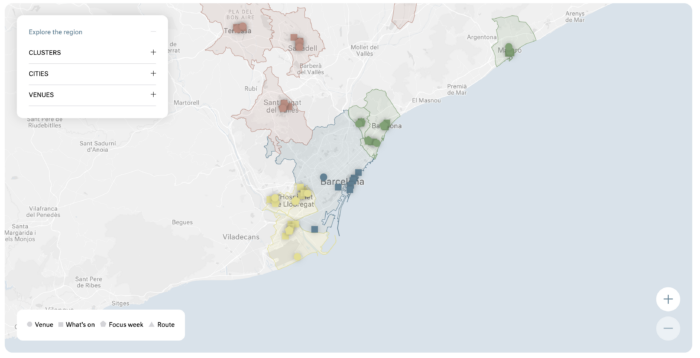

In its purposes, Manifesta 15 intends to “reimagine the relationship between the built and the natural environment,” transgressing the natural boundaries of the city and including three geographic locations surrounding Barcelona to engage its metropolitan area. Structuring across three corresponding thematic clusters, namely that of “Balancing Conflicts”, “Cure and Care”, and “Imagining New Futures”, Manifesta 15 called into play a total of 11 cities and their communities, involving them both in the biennial preparation, organisation, and attendance––hopefully. As we read on Manifesta 15 website, “In the Bid for Manifesta 15, the City of Barcelona formulated the goal of decentralising the cultural infrastructure through creating a new cultural institutionalism, creating a biennial framework which would incorporate the Metropolitan Area.”

The aim of this edition seems thus to be that of decentering visitors’ interest and the biennial venues off from the city centre––the most visited part of the region––to less well-known surrounding areas, bringing these cities, art communities, and institutions on the map. Dwelling on a pre-biennial research study carried out by Sergio Pardo Lòpez, the biennial First Creative Mediator, from the summer of 2021, Manifesta has initiated a partnership with the eleven cities joining Barcelona’s Bid advanced by the then mayor of Barcelona, Ada Colau. The challenge was to connect them with Barcelona’s centre while fostering collaboration among them.

As a response to this challenge, Manifesta has investigated the demographic, environmental, and social composition of the metropolitan area of Barcelona, individuating Lòpez as the main referent of this process. Based in New York City, Sergio Pardo Lòpez is the Director of the Percent for Art Program at the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs. Acting as an advisor for the biennial, with a background in architecture and art administration, Pardo produced an essay summarising “all the different visions of the city” that provided a conceptual framework for Manifesta’s curatorial topics. In his own words, the question directing the biennial was, “How can contemporary cultural creation—especially that which is bottom-up, participatory and interdisciplinary—help stage and develop alternative models to address these socio-ecological challenges and identify how those models can be put into action?”

In turn, being the challenge so ambitious, as an institution Manifesta has been called to rethink its own operational agenda on the field, introducing new models of decentralisation in terms of curation, organisation, supervision, and involvement of internal and external, local professionals. The second creative mediator, Filipa Olivera, has been appointed for the development of the artistic programme, in coordination with Manifesta 15 team and the conceptual framework provided by the First Creative Mediator, mediating in turn the relations with: ten collectives engaged in the realisation of site-specific projects, citizens involved in each of the involved cities assemblies (collecting and monitoring their feedbacks), and eleven artistic representatives ensuring the cities’ involvement and representation in the biennial––thus substantially act as mediator between the biennial organisation, local administrators, and art operators, under the advice and supervision of the Director and Founder of the biennial, Hedwige Fijen, of course. Quite a complex machine to think about.

The pre-biennial research has come to represent a pivotal point of departure to Manifesta since its inception. However, it has updated the format since its edition in Palermo in 2018, when an urban-led, multidisciplinary study of the city was commissioned to OMA, the Rotterdam-based architectural studio firm. Already mobilising the urban dimension in the Manifesta 6 in Donostia-San Sebastian, the 12th edition of the biennial, relating to the charged context of Southern Italy and Palermo, became paramount to the biennial format.

As a result of this process, an eco-social “Magna Charta”, in the case of this 15th edition, supporting the realisation of “an alternative ecosystem for the residents”, has been issued, informed by a “green and social justice agenda.” And while the city’s administrators have changed, including the mayor Ada Colau, replaced by Jaume Collboni, the biennial has continued along the lines indicated in the preparatory study to connect the “region with the nature and the cities between them,” overcoming the unwieldy, hyper-touristified, protagonism of Barcelona city centre.

The Clusters: An Overview of the Biennale

The three thematic clusters mentioned before are scattered across three completely different geographic areas of the metropolitan area of Barcelona––an intense time-challenging effort for participating audiences. The first cluster, “Balancing Conflicts”, involves the area of Llobregat and exposes the conflicts between a city in constant bulimic expansion, through the construction and advancement of its infrastructures, such as the airport, located in El Prat, or the port, among others, and the fragile ecosystems that surround it.

Situated in the Southern part of the city’s metropolitan area, the “Balancing Conflicts” cluster involves three venues and revolves around the struggle of the Llobregat Delta, a natural area posed under threat by the relentless urban sprawl. Including 24 artists, this cluster’s main venue is Casa Gomis, a modernist construction designed by Antonio Bonet Castellana located next to a lagoon called La Ricarda and in the Delta’s Nature Reserve. Sitting at the edge of today’s growing airport zone and on the coastal line, this private house, now reconverted into a cultural centre, was built between 1949 and 1963 and was the meeting place for several Catalan intellectuals during Franco’s dictatorship years.

Here, the biennial has featured a group show that deploys across the house’s rooms, revolving around mainly ecological and historical themes. Among them, Chiara Camoni’s group of installations, including Cani (Bruno e Tre), 2024, two dog sculptures quietly awaiting on a wool rug in the living room of the house, and the Vasi-Farfalla, 2020-2022, a series of organic-looking vases standing on the beautiful view of the windows’ landscape of Casa Gomis. Both the mentioned artworks are not new productions but readaptations of existing works by Camoni.

Some sneak peek from the show might be Ana Mendieta’s Ocean Bird (Washup) photos from 1974 posed in dialogue with Fina Miralles’ transformational photo series where the artist offers her body to nature, turning into a tree (1974); an organic sculpture made with bones and wastes by Ruta Putramentaite, Home no. 1, 2023; Lola Lasurt’s in-archive research and installation featuring documents and a series of paintings inspired by the Els amics del Sol naturalist movement, a collective from Barcelona sensitising audiences on natural and environmental issues active around the 1910s; along the lines of activist movements there surely is the Embassy of the North Sea collective, whose installation Not Illegal Fishing Competition, 2024 “explores the conflict between preserving local ecosystems and the ethical treatment of invasive species.” In a similar way to Elmo Vermijs’ video and architectural installation, dwelling upon more-than-human legal rights with a fictional trial in the architectural tribunal placed in the beautiful gardens of the Casa Gomis.

Notwithstanding the luring value of the venue, the varied composition of the works spanning installation, photography, video, archive, and newly produced artworks, as well as preexisting works, the exhibition, in my opinion, succeeds with modesty to present a coherent ensemble of works variously touching upon some topics but without standing up with any particular highlight, or audacious curatorial solutions in terms of display or narration––which leads me to question the parameters by which I usually personally evaluate exhibitions. I will come back to this point later on in this essay.

I went to the venue twice, the second time before catching my flight back to Italy, trusting the place’s proximity to the airport. To my predictable surprise, notwithstanding the geographic closeness of the house to El Prat, the latter is so extended across the area that it takes around thirty minutes to go around it and access the departures. The exhibition, overall, did not stay with me nor impressed me as much as the modernist venue did, with the beauty of the place and the abiding noise of the planes taking off a few kilometres away. The place, instead, truly embeds the “struggling” of a private, elitist place coexisting with the vertiginous modern expansion of the city upon the delta’s reservoir.

The second thematic cluster of the biennial “Cure and Care” is instead scattered across the Collserola massif and includes the city of Terrassa, Granollers, Sabadell, and Sant Cugat del Vallès. As the title clearly states, the thematic motif is centred on “cure” towards each other as humans, in a socially sustainable way, and the environment. The leading venue this time is in Sant Cugat at the homonym Monastery, where another group show awaits visitors. This time, works by José Bedia, Judy Chicago, Simone Fattal, along with the Italian Bea Bonafini, Diana Policarpo, and Marianna Simnett, differently address human relationships with the “more than human” examining in diverse ways the social, ecological, and political implications of such connections.

Two outstanding presences in this year’s biennial edition were Jonathas De Andrade and Eva Fabregas. De Andrade’s videos are featured in two venues within the “Cure and Care” section, respectively, in the Vapor Buxeda Vell in Sabadell, a former textile factory, and the Natural Science Museum in Sabadell. The latter is a film screened in the middle of the museum’s garden featuring young workers from a zoo interacting with a snake while being investigated by the camera’s eye in their most private cavities––such as the ears, mouths, armpits, in an almost deforming way to the point that the human body discloses uncommon perspectives which highlight the more-than-human parts in the human body. The video installation presented at the Vapor Buxeda, instead, is a moving, colourful piece recorded in the streets of Brazil featuring non-professional actors belonging to a precarious street community of homeless, drags, kids, and passersby acting in front of the camera, which looks at them adopting Augusto Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed approach, thus transformation the viewers on the other side of the screen to the actual spectacle.

Last but not least, the “Imagining Futures” cluster features in four more cities and includes the cover image of this year’s Manifesta, the Three Chimneys leading venue in Sant Andrià De Besòs, and the panopticon vision of the former M|A|C Prision in Matarò, among the others. The last cluster looks like the central cluster of the biennial, as it features the Three Chimneys industrial archaeology site where the most “biennial artworks” are featured, big in scale, spectacular in their effect, and impressive in their site-specificity.

The cluster sits on a part of the metropolitan area of Barcelona, which arguably coincides with its suburbs, as connected to the Besòs River and the disordered urban sprawl of a part of Barcelona’s expansion. The cluster is the closest one to Barcelona’s city centre. A couple of guys, on the cab back to the centre at the end of Manifesta’s opening party, told me they had never been there before, notwithstanding they have been living in Barcelona for most of their lives and working in the touristic sector. The opening of the Three Chimneys, an amazing industrial ruin, looks surprising and promising to them as spokesmen for residents in the city that, as is often the case, have never fully experienced the entirety of the surrounding territory they live in.

The Three Chimneys is the most “biennial” exhibition of this edition. Large-scale installations such as Kiluanji Kia Henda’s The Frankenstein Tree, 2024 depict nature’s resilience against human intervention and damages, hinting at the wildfires that occurred in the Catalan region in 2022 and trees’ capacity to grow back against human-threatening interventions, which is in turn a deeper reference to Angolan colonial histories and aftermaths of the civil war. Similarly, Carlos Bunga’s new commission is a field of metamorphosis and visions rising in the concrete depths of the thermal power station dismantled in 2011 where the artworks are. Delineating the future potential of this site, touching upon motifs of rebirth, resilience, and anti-colonialism, these works, as well as Asad Raza’s minimal intervention with a set of waving, white, enormous, diaphanous flags, agitated by the soft wind entering in the building (the work is titled Prehension, 2024), aggrandize this place’s possibilities.

Similarly, Matarò’s MAC Prison, a former prison now home to a contemporary art centre, in my opinion, is one of the most successful exhibition projects featured in the biennial programme. The panopticon architecture of the place, paired with the architectural intervention of the Spanish artist Domènec with a project on the concentration camp readapted for the space of the MAC, or Eva Fabregas organic, sensual, bloated, coloured bodies invading the cells of the prison, all contributed to the sense of blending and dialogue of the works with the site and its complex history.

Conclusion

Before concluding this article, I want to acknowledge how many things, works, and places have escaped my view and attention. So doing, I want to remark on the extensive status of this biennial and, while underlying a character which is “perennial” to most of these large-scale exhibitions, that is, the impossibility to see them in total, and on the other hand I would like to shed a light on the unconventional character that distinguishes Manifesta and this year’s edition.

As I’ve mentioned, I’ve found myself questioning what the parameters and criteria I would usually adopt to look at a biennial are, assuming that my view corresponds to the average art professional visiting the biennial. In this sense, I cannot help but notice that a significant part of this Manifesta features “minor” works, readaptations, or not-astounding pieces in terms of impact, scale, spectacularism, or else, on the other hand, I think this is precisely the point of Manifesta, this year more than ever.

Considering the long distances from one venue to the other, the (so far) unlikely system of transportation it should entail to guarantee an intense, ready-to-consume experience, as we/us art visitors would expect from large-scale exhibitions, I think that Manifesta 15 in Barcelona asks us to shift the perspective and look somewhere else outside the frame. At the centre of the stage, as it were, are not anymore, or exclusively, the artworks and the aesthetic experience we expect to face when embarking on a visit to the biennial. Quite differently, I think that Manifesta 15 is trying to shed light on different ways to experience the places and the cities we are in, looking at unexpected routes, derailing from the most common destinations and asking for something different, which might ultimately coincide with a cultural approach to tourism and envision alternative (read sustainable) ways to live in nowadays crowded metropolis––in ways that are suggested and elicited by contemporary arts.

The covid aftermath has also impacted the biennial format. The urgency to live outside cities has allowed to single out the suburbs and the countryside’s privileges. [3] This created, in turn, the necessity for city administrations to look outside the centres. I was surprised by how little the biennial was part of the city vibes this time, to the extent that walking around the Ramblas or the Arc de Triomf you would never tell Manifesta was in town. It is this model, this form of not ego-referenced approach to the biennial experience, that Manifesta is asking us to embrace, illuminating new ways of conceiving urban and cultural planning, interinstitutional cooperation at a local and international level, dismissing what the wicked expectations large-scale and a festivalist thinking asks for.

On top of a capillary biennial edition, diffused in distant locations, relating to different places and communities, Manifesta has conceived and programmed a learning and educational agenda which we cannot thrive in on this occasion, publishing three books that respectively investigate the biennial clusters and framework through a collection of essays, further explanations about the programmes, and a visitor guide. The latter is engineered as a proper city guide with references to the exhibitions, artists, and artworks, but also curiosities to know about places leads to eating and drinking, and maps to orientate.

In this sense, I think Manifesta has furthered the urban exhibition and biennial device by integrating its format with a sort of augmented “lifestyle” model to visiting cities as a sustainable approach to the 21st-century touristic consumerism of urban experiences.

A work from the “Cure and Care” cluster has particularly struck me, it is Antoni Miralda’s Milk, Coca Cola and Balut, 1986. The film, realised in the 1980s for an exhibition about Barcelona, has been recorded in Barcelona in the Philippines, a former Spanish colony. The artist researched all the “Barcelonas” in the world, discovering up to forty of them all around the globe, and ending up visiting the one in the Philippines.

Miralda, whose work has always been devoted to exploring collective rituals, recorded the video on the occasion of local celebrations for the Holy Week, focalising his attention, in particular, to a girl reenacting the crucifixion which, after the function, recovers from the effort drinking milk, Coca Cola and balut––a fertilised goose egg realised according to a local recipe. The video, generating from a pun on the invitation to make a work about “Barcelona”, ultimately delivered a more profound critique of the Western-centric habit of looking at the “other” with a stranger gaze that undermines a sort of superiority. The artist’s intervention points out the differences, but also the similarities, that connect very different places in the world, not necessarily in a positive way––such as the exportation of consuming goods, like the Coca-Cola, or the catholic habits imported by Spanish colonialism.

In this sense, I think this film can be considered paramount in the approach to reading and decolonising our understanding of this biennial: in a way, we could say that we can find a piece of “Barcelona” today in almost everywhere in Europe and beyond, and this, not necessarily for good. The elements that make Barcelona similar to other places indeed contributed to erasing differences and eradicating local knowledges, local inhabitants, or individuated social patterns that were replaced by more international, globalised ones––like when a neighbourhood is gentrified by the first arrival of the “creative class” of artists and the like, which starts a process of estate speculation that often ends up with the moving out and replacement of residents because of the surging in the cost of life.

On the other hand, this work suggests that there exist shades and degrees of survival of local knowledges. And for this reason, it does not make sense anymore to differentiate between a “local” and a “global”. Our effort, instead, should be the existence of “translocal” sites that spur from the encounter, clash, and blend, eventually, of different drives at play in our everyday realities in cultural, social, and environmental terms, among the rest. Our mission as “cultural operators” is to preserve and ignite with always different energies and stimuluses such a clash. In a way, in a similar manner to what Manifesta 15 asks us to do: envision alternative ways to route into the future in more sustainable ways, starting from our cities.

[1] Initially, Manifesta relied on a funding system provided by a large array of European countries not necessarily represented by the work of artists featured in the biennial. This system was lately replaced by other modalities, including the hosting city’s bid, sponsorships, and partnerships with other EU organisations, such as The Soros Centers for Contemporary Art (SCCA) Network in Centre and Eastern Europe. A pivotal role, however, has always been that of the Dutch State, where the Manifesta Foundation is located (Block, Hedwig, Hughes, & Néray, 2005).

[2] According to June 2024’s approved budget publication on the Manifesta 15 website, the City of Barcelona secured slightly more than 5 million euros in funding for the event, along with 1 million and 1.2 million euros funding, respectively, from the Generalidat de Catalunya and the Diputaciò Barcelona, constituting circa the 84% of the total budget for this Manifesta edition (Manifesta 15, 2024).

[3] As a matter of fact, in the Manifesta 15 catalogue, Hedwig Fijen quotes a recent exhibition by the OMA studio of Architecture at the Guggenheim Museum in New York titled Countryside, The Future, dating back from 2020 (Guggenheim Museum, 2020).

Bibliography

Block, R., Hedwig, F., Hughes, H. M., & Néray, K. (2005). How a European Biennial of Contemporary Art Began. In B. Vanderlinden, & E. Filipovic, The Manifesta Decade Debates on Contemporary Art Exhibitions and Biennials in Post-wall Europe (pp. 189–200). Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States: MIT Press.

Manifesta 15. (2024, June 13). Transparency. Retrieved October, 2024 from Manifesta 15: https://d18gv4q59iquz2.cloudfront.net/Approved_Budget_June_2024_Fundacio_Manifesta_15_Barcelona_8e40b9c715.pdf

Fijen, H. (2024). Barcelona: Beyond the Walls. In Manifesta 15, Barcelona: Beyond the Walls (pp. 7–21). Barcelona: Manifesta.

Manifesta 15. (n.d.). Manifesta 15 Barcelona Metropolitana, upcoming . (M. 15, Producer, & Manifesta) Retrieved October, 2024 from Manifesta 15: https://www.manifesta.org/editions/manifesta-15-barcelona/about

Lòpez, S. P. (2024). Creating a framework for eco-social transformation. In M. 15, Barcelona: Beyond the Walls (pp. 23-29). Barcelona: Manifesta.

Guggenheim Museum. (2020). Countryside, The Future. From Guggenheim Museum: https://www.guggenheim.org/exhibition/countryside

Evans, G. (2001). Cultural Planning: An Urban Renaissance? London: Routledge.

Schjeldahl, P. (1999, June 27). Festivalism. The New Yorker.