Traces of Contemporary Landscape

From the exhibition TERRENO to the anthropology of the territory

Walking through the exhibition TERRENO. Tracce del disponibile quotidiano curated by Lisa Andreani, at MAXXI L’Aquila, I couldn’t but reflect on the concept of landscape. It is the complexity of the themes explored in the exhibition through material culture artefacts, artworks, photographic documents, editorial materials, poetry, design and architecture projects, all developed within the definition of “available everyday” as envisioned by Gianni Celati, which renders explicit a path dedicated to the “unseen”: scenes, gestures, but above all landscapes of the everyday world, of cultures.

In this project, the mundane is presented through the perspective of a peripheral horizon, with the mineral weight of things and the earth, and with a sense of wonder that is not necessarily found in something exceptional but also in life’s simple everyday beauties. The landscape’s interaction between natural and cultural dimensions is explored through its anthropological, artistic, and philosophical connections. The works on display evoke links between stories and objects that, at first glance, may seem distant but are intertwined by a subtle relationship between what is ordinary and what is tradition, between historical documentation and fiction, creating new possible ways of sharing and focusing on personal narratives.

Within the museum spaces, in a lively and imaginative dialogue, works by artists such as Franco Assetto, Amedeo Aureli, Yto Barrada, Gianfranco Baruchello, Henry Martin, David Blamey, Diego Carpitella, Luciano Caruso, Giuliano Longone, Cavart, Giorgio Ceretti, Pietro Derossi, Riccardo Rosso, Continuum, Mario Cresci, Claudia Durastanti, Francesco De Melis, Formafantasma, Francesco Garnier Valletti, Luigi Ghirri, Ezio Gribaudo, Illustrazione Abruzzese, Enzo Mari, Ana Mendieta, Bruno Munari, Ramona Ponzini, Quarto di Santa Giusta Centro Multimediale, Moira Ricci, Annabella Rossi, Bernard Rudofsky, Marco Schiavone, Shimabuku, Alessandra Spranzi, Susan Sontag, Superstudio, Luca Trevisani, Nico Vascellari, Luca Vitone, and a wide selection of artefacts and documents loaned from the Museo delle civiltà in Rome are interwoven.

While browsing through the texts in the volume published on the occasion of the exhibition project, it is no coincidence that I came across writings such as Incontriamoci da qualche parte vicino al centro. Riflessioni sullo spazio limite tra vita e arte by David Blamey, How to imagine: a Narrative on Art, Agriculture and Creativity by Gianfranco Baruchello, and La tavoletta e il campo arato: una meditazione su natura e cultura by Tim Ingold. The latter, in particular, provides the most substantial connection to the concept of landscape in the modern and contemporary reading of the term.

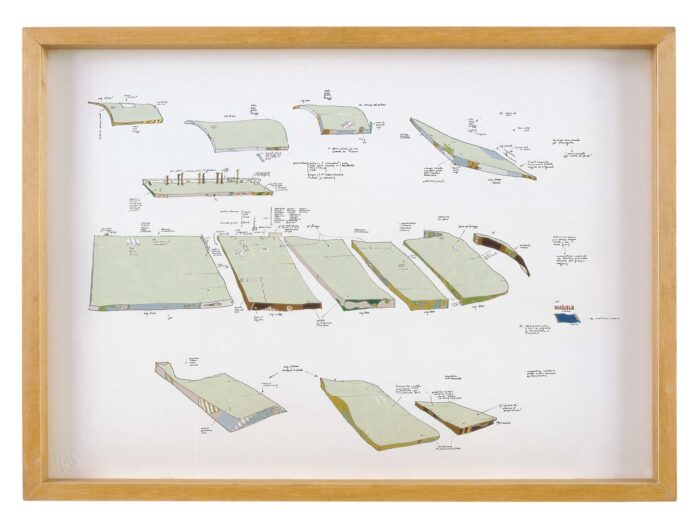

Shimabuku, Onion Orion, 2008. Courtesy the artist and ZERO, Milan. Illustrazione Abruzzese. Feste e Riti in Abruzzo, 1984 – Pescara: Veniero Luigi de Giorgi editore. Private Collection. Photo Claudio Cerasoli. Courtesy Fondazione MAXXI.

The concept of “landscape” in painting has a precise date of birth: it is in 1552, when Titian uses the word for the first time in a famous letter to Emperor Philip II, fully aware that he was at the forefront of a significant revolution in the history of painting. The idea of the modern landscape was born with Titian: a new concept of the natural environment and its relationship with the human figure, developed by the painter starting from the first steps in this direction taken by his Venetian contemporaries, Bellini and Giorgione. It was a true poetic revolution that, in a few years, transformed the landscape from a simple background to a true protagonist, from a mere backdrop to an actor in the pictorial image, which it is idealized by becoming expression, colour, poetry, and feeling. In the 15th century, a detached and panoramic view of the landscape emerged at the dawn of modernity. It presents itself as a frame, a cut, a point of view that, through dynamic perception, enhances, selects, and hierarchies. The landscape, therefore, places the subject in the role of the spectator, observing from a particular perspective (as in Alberti’s definition of painting).

To talk about the landscape, as suggested by the exhibition, means to consider both the tangible physical characteristics of an area—land, reliefs, climates, vegetation, and animal species—and the intangible aspects, such as relationships, the mental, cultural, and social dimensions. Already in the 1930s, studies by new geographers on the landscape were intertwined with the agrarian research of the historians of the Annales d’Histoire économique et sociale, an international journal founded in 1929 by Marc Bloch and Lucien Febvre, which emphasized the role of civilizations and societies in the construction of landscapes, with an interdisciplinary approach that intertwined history, economics, geography, sociology, and anthropology to analyze the deep structures of society and long-term processes. The goal was not only to explore events but also the economic, cultural, and social dynamics that shape human history.

The landscape, therefore, ceases to be a simple “scenario” and reveals itself as a complex, dynamic, and problematic reality. The humanized landscape is not understood primarily through what is visible but rather through the “civilization factors” that shape it. Landscape is a concept in constant evolution, the object of increasing interest from numerous disciplines, which examine it from ever more varied perspectives. It is a term that serves as a meeting point, charged with existential, scientific, and aesthetic meanings. Therefore, it is crucial to reflect on the landscape experience and analyze the contexts and processes through which we interpret it: landscapes, understood as intertwining meanings and symbols, change according to individual and collective sensibilities.

The French school of Toulouse, led by Michel-Jean Bertrand in the late 1970s, contextualized the science of landscapes in dynamic terms of interaction. It provided a historical perspective on the study, combining social history with ecological history, placing nature and natural phenomena within a social interpretation. Bertrand, in particular, situated the analysis of the landscape between nature and society, renewing ideas and methodologies related to the landscape approach.

Eleonora Fiorani says, “Together with space and region, it has been a central concept of 20th-century geography, gathering a collective imagination between literature, art, and science. Nature is transformed and seen through the actions and eyes of man. It thus plays on a double meaning: it indicates the thing and its image.”

Thus, it plays on a double meaning: it indicates the thing itself and its image. Around the concept of landscape, important philosophical and anthropological issues have intertwined. One of these concerns, for example, is the dualism between territory and landscape, up to the question of representation: whether the landscape is understood as a symbol (a set of signs in which subjectivity plays a role) or as a model (a rational construction that explains an external reality).

“Landscape is an ‘umbrella’ word,” wrote Franco Farinelli in 1991, saying that it holds different meanings depending on whether it is seen as a mouse or a bird. Thus, the landscape is both the thing and its representation; it is reality, and the gaze upon that reality, and the gaze is no less important than the reality itself. Hence, it is ambiguous, presents various angles, and clusters epistemologically relevant issues around the concept of landscape, from territory-landscape dualism to the gnoseological issue of representation and reification. Depending on whether it is understood as “a symbol,” a set of signs in which subjectivity matters, or as “a model,” it is a rational construction explaining an external reality.

The landscape has been a central concept in 20th-century geography; it is a modern concept that presupposes a confident posture of the subject, who contemplates it from a distance in the process of “detachment,” and it is always the result of history, a way of working, and a cultural and social vision of the natural world, and is thus subject to multiple forms and modes: a forest, a plant, a stream, a mountain, or a rock will never be perceived in the same way from one culture or language to another.

Therefore, the landscape’s idea, sense, and even taste are a mental construction, both cognitive and aesthetic, reflecting the changing image of nature as a peculiar form of modern human sensitivity. The evolution of the gaze on the landscape mirrors that of subjectivity, with its social and cultural conditioning, and cannot be dissociated from a broader history of the subject. Various elements intersect in the landscape: there is the social aspect of dwelling, building, and representing, with different modes of description and analysis, with shared codes of representation, with policies of protection and destruction, and there is the subjective aspect of emotions and dreams.

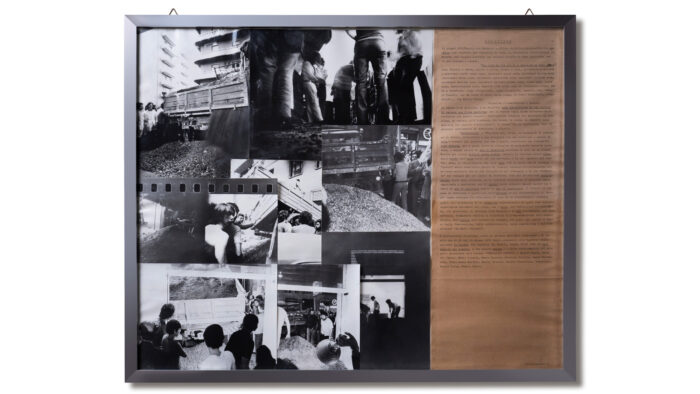

Continuum (Luciano Caruso con Enrico Bugli, Mario Colucci, Mario Diacono, Gabriele Gallina, Laura Marcheschi, Stelio Maria Martini, Emilio Piccolo, Felice Piemontesi, Rivieccio, Emilio Villa, Franco Visco), Operazione Vesuvio, 1972. Courtesy Archivio Luciano Caruso, Florence.

According to Pierre George, a prominent 20th-century French geographer associated with “humanistic geography,” landscape means the scenario offered by nature to settlement and human activity; the set of forms and colours that, with its statute, is realized in art and is also the object of critical, theoretical, and cultural description; the characteristic way of life of a civilization, with all its general and particular effects. These three definitions highlight the clear difference between landscape in the strict sense, as a work of nature, and the organization of human activities. However, for the French geographer, this division does not exist objectively but represents the ambiguity of geography, understood as a “science with two faces.” The most valuable and valid definition of landscape in this context is that of Vidal de la Blache, who defined landscape as a “way of life,” the result and way of life modes, symbiosis, or continuous relationship with nature, plants, and animals.

New space research has highlighted how the landscape is the result of labour, mentality, and the vision of civilization. It can be seen as the fruit of human efforts. No landscape bears the mark of this incessant work, which may have been accumulated, perfected, deteriorated, or transformed over time. In this sense, landscape, like place, reveals a much greater depth than the word “environment” suggests: it contains a history and meaning and represents the experience, passions, and aspirations of a community or people.

It is a space that responds to the existential behaviours of daily life. For this reason, studies on it imply the analysis of human attitudes toward it and its symbolic properties. Humans attribute symbolic value to the landscapes they live in. Landscapes represent an opportunity to question our relationship with places, things, and other living beings. Landscape is not just a way of organizing space but also a form of “intelligibility of the real” or a symbolic mediation that structures our relationship with reality. Thus, in its presence and various manifestations, landscape speaks to us of changes in social space, historical and social conditions, and the imaginations of those who have constructed it and participated in the social space itself.

As linked to civilization, it carries with it our identity, our projects and their outcomes, and resonates with the styles and elements of scientific and artistic activities and inventions. In contemporary times, the landscape is increasingly linked to the concept of “place of memory,” where, as Pierre Nora observes, what we are no longer is inscribed and where we search for our other identity. The concept of “place of memory” is highlighted in the book Les Lieux de Mémoire, published under the direction of Pierre Nora between 1984 and 1992. The term entered the French dictionary in 1993 and has become commonly used. Nora uses it to describe the contemporary sense of the “loss of landscape.”

The death of the landscape

Our contemporary era is characterized by the presence of technology, the de-biologization of territory, pollution, the homogenization of urban landscapes, and the acceptance of coexisting with destroyed environments such as quarries, mines, and industrial ruins. Modernity seems to experience the death of the landscape, visible in urban peripheries and the progressive deterioration of cities: a crisis of values reflected in their very forms. Even the idea of spatial rationalization, with its separation between work, residence, and leisure, has weakened.

At the same time, the homogenization typical of industrial society is now countered by fragmentation within mass societies, where different communities claim their own culture, history, and identity, whether authentic or constructed, transforming into centrifugal forces oriented toward general diversification.

Never before so much attention has been paid to the beauty of rural and urban landscapes and even the ethics of quality of life. However, rather than a change in attitude that could genuinely transform how we live and inhabit the Earth, what is happening is an aestheticization that only decorates the surface. An aestheticization with tourist connotations that erases historical economies and conservation, if separated from its context, can lead to regressive developments. Protection and aestheticization are often accompanied by indifference to environmental issues and disinterest in areas that do not possess picturesque characteristics.

In fact, natural parks, recreational or reflective spaces, and sacralized places as symbols of a rediscovered naturalness (to visit, to observe) are or are becoming spaces of representation. Rather than compensating for lost nature, these natural spaces, intended to preserve a “memory of nature,” now justify reification and reification, precisely what the natural landscape risked under the weight of technological, economic, and social development.

The concept of the “playful dimension” of the landscape and the theatricalization of the territory are increasingly present in the debate. Tourism drives the transformation of entire landscapes, while the decorative character of places, with their staging, reflects the spectacularization of the late modern world. The current tendency to turn everything into a spectacle—from history to exoticism and localism—leads us to live increasingly detached from the territory.

After the loss of landscape in the historical sense, we have gradually come to survive in a “non-place,” as defined by the French anthropologist Marc Augé. The concept of non-place defines architectural and urban spaces of transitory use characterised by two complementary aspects: their physical structure and the particular relationship that people establish there. These spaces, which include airports, shopping malls, stations, highways, and even refugee camps, are contrasted with traditional anthropological places by their lack of identity, relationships and historicity.

Non-places are products of surmodernity, designed for impersonal use and devoid of psychological appropriation, where the movement of users is mainly guided by signage. Characterised by a high degree of technical standardisation in lighting, pathways and acoustics, these spaces communicate through symbols and pre-recorded instructions, reducing the individual to the sole role of user or client.

Paradoxically, despite their homogeneity, non-places are perceived positively by users, who find comfort in their overall predictability. Indeed, a lost traveller can find a sense of security precisely in the anonymity of these standardised spaces. Rarely existing in pure form, places and non-places are often interconnected and emblematically represent our age, characterized by precariousness, temporariness and solitary individualism.

We need an anthropological, philosophical and artistic perspective to interpret the new meanings inscribed in contemporary territorial actions and their double polarity, where place and space oppose and complement each other.