Towards A Better Ending

“The Last Terminal: Reflections on the Coming Apocalypse (Part 4 — The Uncommunicative)” at Rib, Rotterdam

Virginija Januškevičiūtė, curator at CAC–Contemporary Art Centre, Vilnius, tells us about The Last Terminal: Reflections on the Coming Apocalypse (Part 4—The Uncommunicative) at Rib, Rotterdam.

It must be because of my hunger for reading at the time that I recall my experience of the exhibition starting with the mezzanine. Adjacent to a roof terrace inside a housing block in Rotterdam South, there was a work by Marije de Wit, consisting mainly of excerpts from various books. I could barely truly grasp any of it in the short time that I visited but I felt so drawn to these texts that very quickly I started seeing the rest of the exhibition as a play of various instances of their effects. Every part and every aspect of the exhibition was now as if elevated by its relationship to something that presented itself largely as a mystery to me: snippets of writing, titles, names, and ways in which all these things seemed to relate to one another.

The exhibition had in fact begun a few months earlier under the premise of Rib revising the notion of its own finitude: the uses of energy that such initiatives take to run, the funding cycles, the turnover of exhibitions, the impending changes in the fabric of the city that regularly push spaces such as this to relocate. Pushing against the exhibition routine and towards a presumed end, Rib’s current exhibition cycle that began in September 2021, The Last Terminal: Reflections on the Coming Apocalypse, contains works that remain in four or five subsequent exhibitions, with many of the artists revising their contribution upon each new instance. New names, forms, artworks are being added regularly, marking the cycle’s division into distinct chapters. The selection of texts by de Wit, Once A Reader, had been added to Part 3 of the cycle, entitled “The Phantasy.” I was now visiting Part 4: “The Uncommunicative.”

Marije de Wit’s piece in the mezzanine was in many ways a more spacious version of her initial contribution to Part 1, “Former Epiphanies, Impressive Moments”–a selection of readings that she had suggested to reflect the themes of Rib’s current program. A collection of quotes from essays, poems and books have now become whole poems, pages, and chapters, providing more context to play with the ideas; a single bound folder of standard paper sheets has turned into a room accommodating the reader complete with inviting and accommodating furniture (by Olivier Goethals). This–a spirit of hospitality, perhaps?–echoed throughout the exhibition: its earlier chapters were patiently and eloquently explained in the exhibition handouts; the layout combined exhibition space with a kitchenette and a bunch of chairs in the terrace which made the otherwise rather dense and crowded exhibition particularly airy; many of the artworks took their places discretely as parts of the design of the space, a corner of the stair, a wallpaper.

To have this, something had to give. Another piece by de Wit, a wall sculpture from an earlier chapter–a light piece spelling the phrase “This Means That Much”–was now shut off and stacked, letter by letter, in an open shelf on the ground floor of the exhibition space. The current state of Kianoosh Motallebi’s From a Marvelous Faucet–a mound of paraffin–provided few clues about its original, presumably much more elaborate form. Pano-Zavaroni’s sound piece seemed deliberately oblique, as if the loudspeakers were shooting fragments of language into space and taking them back before anyone gathers. All of that signalled, however, something very close to the exhibition’s core: disclosure is not required; explanations are there but not necessary. Even more space, then.

A more linear cohesion gave way to a sense of things clicking with one another in a myriad of ways. The works were obviously coming together from slightly different cultures, many of them specific, perhaps, to an individual artist’s studio. Nothing tired, nothing forced. Through the unlikeliness of one work to another their ‘clicking’ appeared even more intense, producing connection, insight and conflict alike.

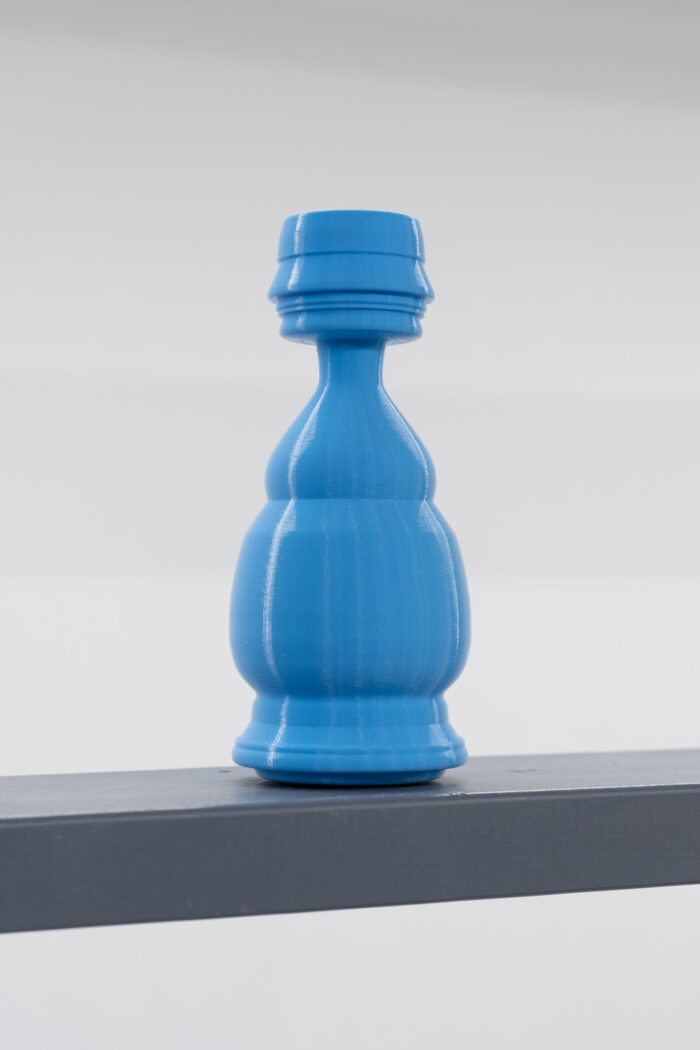

The installation Afspraak Future by Eleonore Pano-Zavaroni pays tribute to a scene in a documentary film by a French director Albert Lamorisse, The Lovers’ Wind (1978), also shown in the exhibition. In this scene a helicopter swooshing by a valley where some carpets have been laid out to dry: caught by the gust of wind (“the wind of love,”) the carpets jolt into the air and scatter across the valley. In Afspraak Future, an array of small intricate objects are scattered across a light carpet-like structure. They look like they have been owned, and some of them have been altered or marked, but we don’t know their stories nor their relation to each other. We don’t know if they will be used again, either, and we are left to wonder.

Portraits of three young impressive women were looking at me from the wall, all three heads tilted towards their left shoulder, lips slightly parted, unruly hair falling across their foreheads and calling for a swift lifting of a hand to brush them from the eyes–a passing moment, in vogue at a certain time in fashion photography, now studied in the series of paintings by Thomas Helbig. There was no other eye in the entire room to meet theirs.

But the amount of text in the exhibition was abundant. Maziar Afrassiabi’s curatorial voice presented itself in writing loud and clear. There was de Wit’s work, reproducing itself in various forms of text, the radio jingles, couple other archives, documents, essays being sent off to media at regular intervals (this very text being one of them). More than anything, however, all those texts seemed to join into a choir speaking of something exactly opposite to producing more text: a frustration, desire, necessity to stop talking. Every word that was written or said seemed to plead for it to be the last one – not the final word, but one last word in their unceasing flood.

UNPLUGGED AND OUT OF EASY ANSWERS, read a LED board amidst Olivier Goethals’ structure designed to hold the exhibition. “We cannot hide the fact that as we go on with our business, feelings of futility loom,” wrote Afrassiabi in the exhibition’s introductory text. “Your excellency,” read an excerpt from Don Mee Choi’s “DMZ Colony” in de Wit’s selection, “I present to you a correspondence of certain grave significance. It’s written in a foreign language. No translators are currently available. The members of your cabinet may not have any tolerance for foreign words or incomprehensibility in general. […] However you, sir, may recognize many of the letters.”

One of the artists in the exhibition, Steve Van den Bosch, answered to the curator’s invitation with a suggestion that the curator describes his future piece in the exhibition. It was understood that the description itself was to become the piece. Friendship, musing on authorship and power dynamics, and legacy of conceptual art all get thrown into the resulting text-artwork. “All this amounts to a lazy trick,” Afrassiabi finally concludes, defeated, after going back and forth over if there is any way that this may end well for him; “the culture of the conceptual art fundamentalists reveals itself. Arrogant escapism as authorship.”

This is not all just in acknowledgment that visual art is a heavily text-based medium, and a push against it. More is at stake: the exhibition returns many times to the theme of art drifting away from everything else in the world, despite the talking. One of the founding gestures of the exhibition cycle was performed by the San Francisco-based artist Mathew Kneebone: he linked together the venue’s electricity circuit to California’s power grid so that if there is a blackout in California, the exhibition venue is unplugged from its own power grid, too. In the exhibition it reads as an attempt to hold art and reality together by the means of a brutal material bond. Next to the manipulated electrical panel Kneebone added also two drawings made by a child, a tiny storyline capturing one recent California blackout.

The bond between art and life is fatal in another initiating gesture, a permanent fixture of the exhibition cycle–“The Lovers’ Wind” by Albert Lamorisse, who perished in a helicopter accident in Iran during the shooting of the film (the documentary was completed by his family and the surviving film crew). With these two key pieces at its heart, the exhibition asks to be forced to a halt; to be stopped in its tracks. It clearly wants me to believe that a certain death is necessary. Not of an artist; but that in order to make sense of any of it, or to bear it when things don’t make sense, something has to change in how we consider art.

The exhibition was a work of a determined gardener, who is very well aware that the garden doesn’t stop growing regardless if it looked after or not. We were summoned here, perhaps, to check on the gardeners’ sanity (‘we’ the writers, but also ‘we’ the visitors). I was convinced. Some pruning seemed due.

A snippet of a poem by Marianne Morris echoed from de Wit’s mezzanine; the poem is called Word / World:

After the culling

when the world dies down

and things again sprout and run wild and go uncontained

and are not sold to nor sold on nor soldered to

a sound like cash

we will hurtle to

wherever

Far from a rally against words, Rib’s exhibition cycle seems to be more of an attempt to escape art’s predictability, its need to engage in promises. Words may not be the way, but here they are relentlessly brought for sacrifice in order to move anything at all.

“I wanted to indirectly (without making it into a theme) connect to the historical developments that lead me to be here and do what I am doing now,” wrote Maziar Afrassiabi, founder of Rib exhibition space, in an email. “So partly it has also a personal aspect. Bringing in that element made me feel that what I started and continued with Rib is but an accident prompted by certain socio-political developments. (After the revolution in 1979 [in Iran], war broke with Iraq and then few years later we fled the country, I was a child then). So in a way it is about breaking free or working with conditions of production and adaptation to certain models of creation and art that I try not to take for granted.”

“It was also clear to me that the idea of breaking free or at least to create a space of alienation in relation to the art world, is probably just a fantasy,” Afrassiabi wrote further. “Anyway, all this led to thinking again about breaks, and ruptures. About changing gears. As you know the program is not about ending or ends as such but also about revelation of something possibly new, which is the meaning of apocalypse in some sense. In the end it’s about a certain unease and misidentification with what you do, and at the same time continuing with that in mind. Ending and repetition or difference hopefully.”

As I passed down that same street later in the evening, the red light from the LED lettering threw itself out the window and fell flat on the pavement, bleeding.