To Those Who Can Imagine

On Gluklya’s artistic practice and exhibition “To those who have no time to play” – Part 1

The first major solo exhibition by artist Gluklya (Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya) To those who have no time to play, curated by Charles Esche at Framer Framed, Amsterdam, comprises a solid body of new works developed by the artist throughout the last five years. The exhibition unites different parts of Gluklya’s past and ongoing artistic research on global and regional outcomes of accelerated capitalism, repressive political regimes, different forms of coloniality and post-colonial conditions, which she investigates in the European Union and its former colonies, in today’s Russia, and in countries that were once a part of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union.

This is the first part of an essay by Anna Bitkina (continuing with New Communities of Care) which intends to serve as a non-linear alternative guide through the exhibition’s contexts and experiences, with some references to Gluklya’s projects that anticipated and informed the exhibition at Framer Framed.

LOOKING BEYOND REALITY

A long-awaited exhibition To those who have no time to play came into sight in Amsterdam in the midst of a very uneasy moment of contemporary political history, when the wrestling between the world powers driven by imperialism has broken out in the centre of Europe (again). The logic of Gluklya’s exhibition, composed as an imaginary living environment with elements of vernacular architecture, resists global world collapse by juxtaposing it with the potentiality of interpersonal kinship and interspecies exchange. Constructed with care, her world demonstrates multifunctional purposes, and the social role of art under capitalism and in the situation of growing political suppression and escalating militarization. Being an outstanding example of creativity and ingenuity, the exhibition serves as a public forum for gatherings to provide trans-regional and trans-personal exchange on common political and ecological history and economic interdependence. Gluklya’s generous and diverse visual language wishes to fill in the emotional void in the time of local and global human segregation caused by wars, racial superiority, social and economic privileges, ideological suspicion even among like-minded people, unresolved historical traumas and contested worldviews, bodily fears, psychological barriers, and biological conditions.

Strongly believing that private life is inextricably linked to political processes, Gluklya follows her artistic principle to be on the side of those whose lives are most vulnerable and defenceless. She often contrasts the language of governmental and militant power with the positions of individuals without a political voice, who are abused by these power structures, underclassed, and labelled within social strata. Fragile lives of individuals whose bodily and physiological states are affected by the political system are at the centre of Gluklya’s creative stories. What exists as a steady state order in the public domain in Gluklya’s exhibition becomes inherently private and is exposed as ongoing “normalised” violence and injustice embedded into different social and power structures. Through her practice Gluklya strives to build channels of interclass engagement to renegotiate the processes that shape contemporary conditions and divisions. Seeing through the eyes of the oppressed, she intends to disrupt the apparent normality of the current situation, and to propose alternative support structures and means for communication.

SCAFFOLDING THE FUTURE

In To those who have no time to play we come across several narratives of individual and collective protest against oppressive institutions of powers. The exhibition could be imagined as interconnected layers and juxtapositions of different personal stories by individuals with intersectional identities as well as embeddings of local and global political processes and times. It’s a journey through the bodies and minds of creative visionaries that have lots in common but would probably never meet if it weren’t for Gluklya’s exhibition, in which she interweaves their lives to stress the significant meaning of the collective and polyphonic exhibition.

Through her visual and performative language Gluklya creates a so-called “visionary fiction”—a method proposed by Walidah Imarisha, an American writer, activist, educator and spoken-word artist whose practice is rooted in the social change movements. Imarisha advocates for a form of “fantastical art that helps us to understand and challenge existing power structures, and supports us in imagining paths to dreaming and creating more just worlds”, stressing the fact that “We can not build what we can’t imagine or see. We should remember to imagine and scaffold the future”. Therefore, Gluklya’s exhibition serves also as a “laboratory of radical imagination” where different geographical locations, political realities, and communities are interconnected.

In order to understand the mechanism and the logic of To those who have no time to play we should try to play with it and deconstruct it, as curious kids who dismantle toys to check what is inside. Keeping this in mind we can start looking at different layers of the exhibition body and dissect it part by part. It should be mentioned that Gluklya initially designed the exhibition as an anatomical experience consisting of structures in the shape of internal human organs—heart, lungs, brain—connected through long red arteries, and we still see some remnants of this artistic vision, but in a modified way.

EXHIBITION BODY

The Stage

The first layer of To those who have no time to play is very architectural; therefore, to have a closer look at the exhibition landscape will require to the viewer the optic of the architect. What stands out first is the two-level stage topped with the red velour canopy, which is given to the main characters: supposedly, alive and dead bodies of Antigone Update, a new version of Sophocles’ classical Greek tragedy contributing to the genesis of Western-centric norms, principles of democracy and logic of justice. Sophocles’ Antigone is considered a “must-read” in European education, focused on the eternal struggle between the state power and the personal (political) will. Being influenced by different readings and studies of Antigone, including that of the scholar of feminist democratic theory Bonnie Honig, in Antigone Update Gluklya questions the notion of power and subverts the idea of individual heroism, love, female solidarity, and “forms of corporeal care”. Gluklya’s work has a potential for legislative imagination which undermines the letter of the rational law and focuses on an alternative set of rights that are more responsive to personal needs, emotions, and beliefs.

All “alive” protagonists of the play are materialised as standing stage costumes with attributes associated to their own characteristics: a soldiery figure Creon; thin, curving, and submissive his wife Eurydice; well-behaved but traumatised, with a big hole in his chest their son Haemon; emotional and in pain Antigone, in a dress also full of holes; doubtful, law-abiding and pierced with a net of blood arteries her sister Ismene; frightened as a bird Sentry; torn by contradictions and doubts the Messenger; wise Tiresias accompanied by a little Boy. The dead body of Polynices is also given agency by being placed at the lower level of the stage, in a niche of another world. To dramatise the antagonism and tension between Antigone and Creon, Gluklya has framed the stage with two red costumes: a ragged wooden mask of Creon screaming in despair and a big dark dramatic flower for Antigone, a men who make the laws and a woman who does what she feels is right. The question of what rightness is is central in the script of Antigone Update.

The architectural structure of the stage is composed as an imaginary microsociety and accompanied by a cohort of humanised sewing machines, which, on one hand, acts as a collective social majority (the chorus, in the tradition of the Ancient Greek tragedy) and, on the other, plays an utilitarian symbolic function; namely, sewing together all the exhibition narratives. The chorus is represented by the costumed characters and figures of different age, gender, social class and emotional intensity. Textile and clothes are one of the main medium and material in Gluklya’s practice, which is described in Two Diaries as an invented language: “For me working with textile is being alive and speaking with myself and the world via non-verbalised surrogate of different desires”. The machines are extended by various biomorphic creatures and white narcissuses produced by textile artist Natalia Grezina that are placed throughout the exhibition space—sonic flowers dressed in blue working blazers found by Gluklya in Amsterdam vintage shops and tree branches merged with sweatshirts with attached books.

The plot of Sophocles’ Antigone, and its contemporary interpretation, is a focal and connecting infrastructure for the exhibition, chosen in a search for an abstract and universal form to reflect on the current tragedy. In the light of the growing political and military trans-regional antagonism imposed by Russia in Ukraine, the moral choice between state order and personal ties confronts millions of individuals with excruciating decisions to take sides which tear apart family members, beloved ones and friends’ unions.

Three other architectural structures of the exhibition are designed as temporal micro-universes with their unique cosmologies.

House of Female Imagination

One of them takes the shape of a Central Asian yurt (боз үй in Kyrgyz), which Gluklya turns from a traditionally regulated environment with a strict division of women’s and men’s spaces [1] into a house of female imagination and care, a domain of listening and storytelling, a place of mastering craft. Artist and architect Benjamin Roth, who constructed the yurt, kept in its design the main traditional elements, such as the top of the yurt (tyundyuk), which is perceived as a unifying beginning in Kyrgyz culture. At the exhibition, it is symbolically marked by a red dress with a raised hand: a sign of liberation and freedom that appears in many different projects of Gluklya as her trademark.

The nomadic home of the yurt has been set up at the Framer Framed premises as a shelter to accommodate the life stories of Kyrgyz seamstresses Dinara, Rakhat, Zaina, and Samira, who work hard in the clothing industry and have no time to play with their kids (hence the title of the show). They struggle from an ongoing bodily and mental violence caused by the harsh labour and poor ecological conditions of the industry, as well as from sexual abuse embedded in working environments and domestic lives of many Kyrgyz households. Their stories manifest the post-soviet colonial conditions and the consequences of regional capitalism by addressing the economy of Kyrgyzstan, where the “slavery” textile industry “forms a major part of the country’s budget. “Almost all clothing produced in Kyrgyzstan is exported to Russia and Kazakhstan to provide low-income segments of the population in these countries with cheap clothes.”

The video installation in the yurt, Gulmira’s Fairy Tales, performed by Kyrgyz actress Gulmira Tursunbaeva, could be interpreted as a collective historical and contemporary female voice of Kyrgyzstan. Its narratives include parts of biographies and dream fragments of Dinara, Rakhat, Zaina and Samira collected by Gluklya through a number of personal encounters with the seamstresses during her trip to Bishkek. Disrupting their automated and zombified 15-17 hours daily working routine, Gluklya conducted a series of listening and creative sessions with them in order to abstract women from their reality and to make space in their minds and working schedule for play, dreams and imagination. The results of these collective creations are presented in the yurt in the form of textile zoomorphic and angel-like creatures.

Interweaving personal stories into the overall political fabric and presenting it in popular media formats is a continuous artistic method of Gluklya, which she also practises in her durational performative project Debates on Division. When Private Becomes Public (2014-2019). The presentation format of Gulmira’s Fairy Tales resembles that of Good Night, Little Ones! (Cпокойной ночи, малыши! in Russian), which from the 60s until now has been one of the most known and popular kids’ TV shows among Russian speaking people of different generations, and an integral part of Soviet identity. In the fairy tales Blue Rabbit, Tango of My Grandmother, Ghost and Revenge Gluklya makes careful editing of contemporary biographies of her heroines and historical memories. The archival records of female emancipation in Soviet Central Asia were collected by Gluklya in Moscow and Bishkek with the help of the researcher and artist Katya Ivanova.

As in many of her works, in To those who have no time to play Gluklya demonstrates not external but internal freedom and strength of her characters. Through the visual tales that contain elements of humour, absurd and grotesque Gluklya endows her heroines with a political voice, incredible will power, creativity, and imagination, by building a continuity of herstory through time, geographies and suppressive political ideologies.

The episode titled Ghost most vividly outlines the suppression of female solidarity and political imagination across centuries. It is based on the memoirs of Elena Solovey (dated 1921), a close collaborator of Lenin, about the visit of politically empowered Central Asian women to Moscow to meet Lenin. The video, performed by Gulmira Tursunbaeva, is a combination of historical facts with fictional parts. Pronounced with deliberately theatrical intonations, the script aimed at translating the heroine’s enthusiasm about a future which never happened because she was killed by her husband due to her active social and political life conflicting with the ideal of Central Asian patriarchy. The video ends with a black and white filming of Gulmira walking on the streets of contemporary Bishkek as a white-robed ghost whom no one notices but is somewhere there, the ghost of freedom. By giving to Gulmira’s Fairy Tales’ installation the subtitle TV for Seamstresses Gluklya foresees a potentiality for this fairy tales’ series to grow to become a common platform for conversations, exchanges, and unity for the female working class, to regain its power and rights.

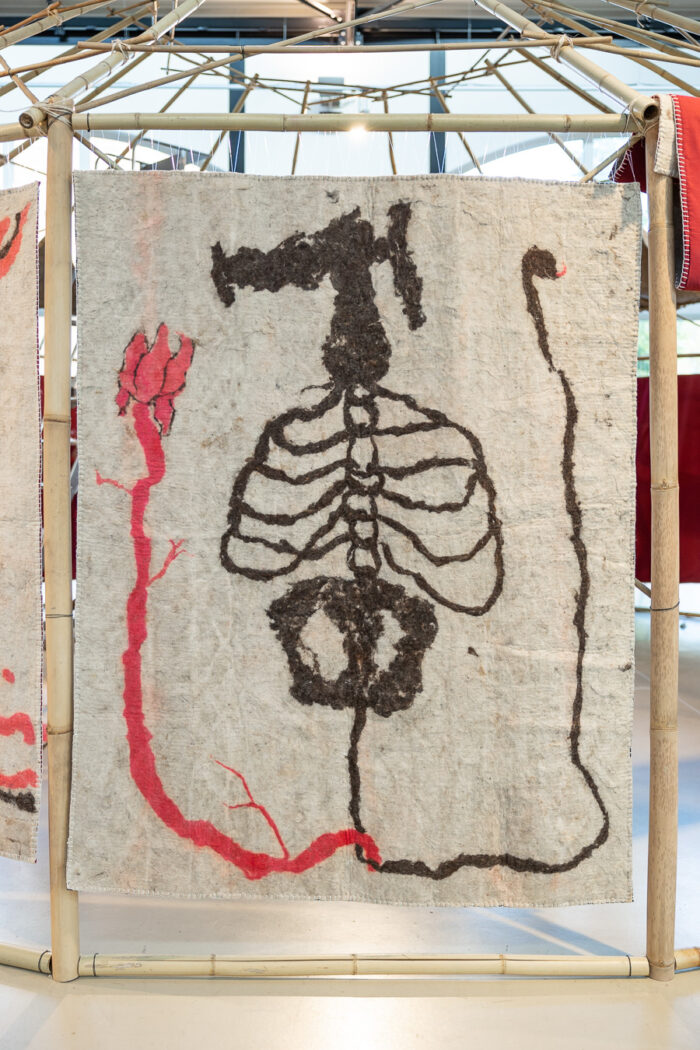

Gluklya decorates the yurt with her graphics, white sheets with red “frantic” stitching and text fragments, textile fantastical creatures designed and co-created by Kyrgyz seamstresses. The yurt is covered and framed with 16 prints, mats and carpets made from traditional woollen felt. To produce them Gluklya collaborated with local craftswomen from Felt Art Studio specialising on the felt pattern rolling technique who rolled into the felt the patterns of Gluklya’s drawings depicting different elements associated to the lives of the Kyrgyz seamstresses and their invisible hard labour: body parts like lungs and ribs that are merged with the sewing machine the women spend most of their time at, the inner ear as a symbol of listening, the clock of endless working time or lifetime stolen by capitalism.

Chapel of Friendship and Affinity

The yurt is neighbouring with another structure that could be called “My Swollen-Hearted Friend” [2], which materialises some aspects of Gluklya’s ongoing research on migration, displacement, cross-cultural misunderstandings, and a search for a common language of care and hospitality. Its textile top looks like a heart taken out of the body, with cut out red arteries and blue veins. This space embraces the story of the Kurdish political activist, refugee and writer Murad Zorava, presented at the exhibition through different elements of design and Two Diaries: Gluklya & Murad, a publication built around an exchange of parallel diaries written by Gluklya and Murad.

Murad and Gluklya met at the premises of the former prison Bijlmerbajes in Amsterdam, where Murad was a resident of the asylum seekers centre (AZC) organised there in 2017. Following the open call by Lola Lik Gluklya, together with other artists and creatives, was offered to rent a studio in one of the prison towers. Later it became apparent that this pop-up creative cluster was part of a major gentrification project by The Bajes Kwartier masterplan designed by OMA, the Office for Metropolitan Architecture founded by Rem Koolhaas and Elia Zenghelis in 1975.

Through their diaries, we learn about the growing friendship and personal stories of the authors as well as their traumatic encounters with the state migration policy and business schemes that were cynically intertwined. The hard life story of Murad makes one’s heart beat faster out of a sense of injustice and helplessness. Although, as he writes, “the outlines of my life story are shared by tens of thousands of people in my country”. He was previously imprisoned for his political views, actions, and for just being Kurdish, and he had to flee his country due to constant political persecution to later find a home in the Netherlands. Gluklya proposed Murad to keep a diary “as a healing and exhaling” practice, that she started earlier to overcome the imposed strict policy of Bijlmerbajes. The writing exercise was also a method for better understanding each other’s inner worlds for both, and an exchange of their experiences being residents of Bijlmerbajes, although in different statuses.

Through the exchange of the diary entries in Two Diaries the authors take us through the labyrinth of the well-meant but still passively violent environment of Bijlmerbajes, which sheds light on the blind sides. Being overorganised and overprotective the system forgets about its announced humane, democratic and inclusive intentions to serve as a welcoming and hospitable space for newcomers. From Gluklya’s part of the diary we learn about Saskia, an elusive woman, head of AZC in Bijlmerbajes, which Gluklya tries to meet: “I have checked the amount of correspondence about asking to have access to the refugee/newcomer’s part of the prison. 267 letters. And still no permission to go freely to the part where refugees are living”. Although losing her hope and feeling frustrated, Gluklya still attributes human qualities to Saskia by meditating on whether she has kids, how she looks like, what book she reads.

It’s quite painful to read about the suppressive space of the former prison Murad had been particularly traumatised by: “This place gives you the feeling that you are under the lock and key and that you will never be able to go outside. A prison in every respect! A field for psychological oppression… I don’t want to be unjust and one-sided in trying to understand it, but I find it very difficult to see the goodness in placing people here”.

The architecture of this Chapel of friendship and affinity has some references to the neighbouring yurt; however, it differs, having a personalised and intimate touch, and an energy that resembles a place of solitude. The floor covered with felt carpets is encircled with many pillows of different forms with reference to Central Asian or Turkic traditions. Incorporating thematic embroidery and texts, these pillows are dedicated to Murad, haunted by the lack of pillows from previous imprisonment nightmares even at the AZC in Bijlmerbajes, where they forgot to put them in his room. The interior of the chapel consists of a bench, or better the Chair for two produced by Roger Cremer, and a standing reading lamp in the shape of a lily flower with the stem as a human spine, placed in the center of the space to invite the exhibition visitors to experience the collective writing of Gluklya and Murad. Another symbol of unity is a drawing of human lungs on the bench back, which is a metaphor of “writing in one breath”, but also transmits the shared breathing conditions of Gluklya and Murad at Bijlmerbajes, where it was impossible to open the windows.

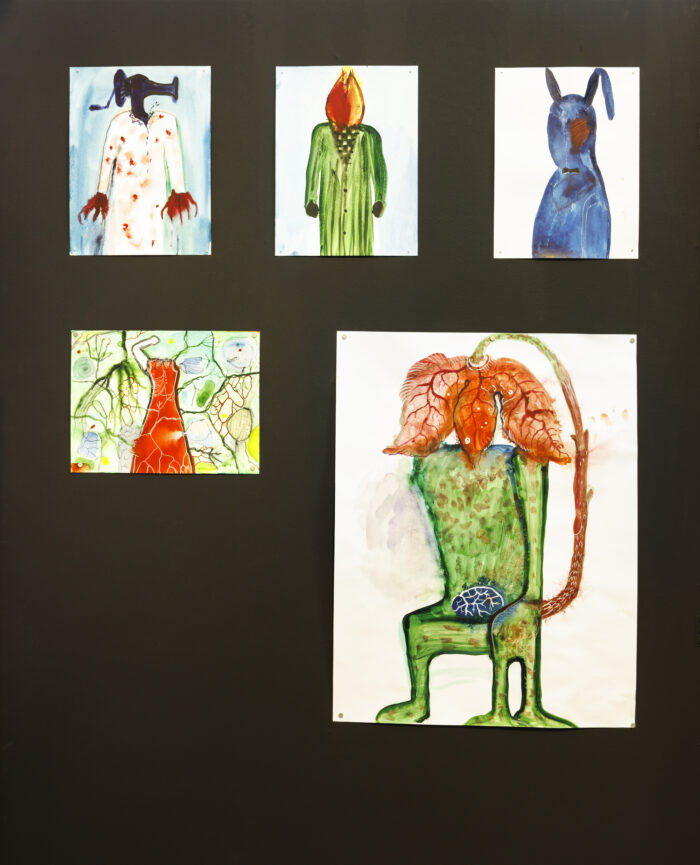

Two Diaries also has the distinguishing feature of an artist drawing book, including 64 drawings and watercolours made by Gluklya as a resident of Bijlmerbajes. All graphic inserts of the book could be divided into three sections of drawings, dedicated to several activities—images that came out during the Language of Fragility workshops with asylum seekers, sketches of characters and costumes for the Carnival of Oppressed Feelings, and different emotional states Gluklya went through during the time of her residency at the former prison building. The themes of Gluklya’s drawings are often associated with animal-vegetative themes, sensuality, empathy, and caring, and characterised by connections she makes between political imagination and ongoing events with existential states that leave traces in the subconscious. The set of depicted emotions that Gluklya transmits through colourful or very dark images in Two Diaries gives different dimensions to the book by captivating the inseparable unity of the body, words, plants, elements of architecture, and fantastic clothes. Some of the original drawings from the book can be seen at the exhibition space around the chapel.

Interconnecting stories of workers from Central Asia and refugees from Turkey, Africa, Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, Gluklya is expanding the geographical scope of global forced migration. For the last months thousands of people affected by the war in Ukraine every day have been making hard decisions to give up their previous lives and relocate into safer geographies. Being disrupted from the way of life, for an uncertain period they found themselves in different temporalities and in the limbo of waiting. The war is still going on, but already now it’s clear that the lives of people in Europe won’t be the same when the war is over. All future scenarios will require international collaboration in order to develop new infrastructures of safety. This collaborative work we must envision already now, in order to have a sensible future, to live happy lives without being disconnected from our lands, homes and families.

Madhouse

Another exhibition structure is Melting Snowball, the white dome serving as a screening space for May 1st, a documentary chronicle of the May 1st demonstrations in St Petersburg recorded by Gluklya and her comrades from 2017 to 2019. Possibly indirectly yet insistently, the installation Melting Snowball is leading to the question how to regain the future and get back what was lost or got taken. This work does not only guide through these three years in the recent alternative political history of Russia, but also intends to look at what has anticipated this period, and speculate about what is next.

Being totally coopted by governmental ideology during Soviet time, in the 90s, straight after the collapse of the Soviet Union in Russia, May 1st got its revival and regained its political meaning becoming a moment of gathering for all political forces from ultra-right nationalists, communists and anarchists to democrats and ultra-left including vegetarians, progressive critical thinkers and conceptual contemporary artists and performers with sharp and provocative banners. To contextualise Gluklya’s video and recall the citizenship issues in post-Soviet Russia, it would be pertinent to bring attention to the film by Ukrainian filmmaker Sergei Loznitsa The Event (2015), in which he revisits the dramatic moments of August 1991—known as Putsch—that lead to the collapse of the USSR. “In the city of Leningrad thousands of confused, scared, excited and desperate people poured into the streets to become a part of the event, which was supposed to change their destiny.” A quarter of century later, Sergei Loznitsa revisits the dramatic event by editing the archival footage that documents the life of the city at the time of a historical calamity and, possibly, the birth of something new. In The Event “we can see how ordinary life turns into history; people’s faces, singular close-ups taken in time, which cannot be found in history textbooks or transcripts of political speeches”.

Being on the verge of the birth of “Russian democracy”, the country turned into a reverse mode. At least for the last 20 years, the Russian civil society has been pragmatically and persistently dismantled through a series of legislative and power apparatuses engineered by Putin and his collaborators. The courage of the ongoing protests now and then has to be considered in relation to the growing number of laws aimed at the severe punishment of any manifestation for citizenship, human rights and freedom of thought. It would also be fair to mention that during this period several grassroots (cultural, academic, social) initiatives have grown and formed in Russia to actively seek to create and popularise democratic principles, and promote the basics of political literacy and critical thinking.

In her lengthy video Gluklya captures the last years of May 1st demonstrations, before it faded out completely in the years of COVID19, when public events were forbidden. The pandemic factor “conveniently” overlapped with the persistent and years-long agenda of Putin’s regime to disintegrate and demolish all possible political forces and alternative critical thinking in the country.

Intuitively understanding that May 1st could provide an image of Russia’s collective political life, Gluklya could barely have envisioned that this footage would become such an important time document. Like the explicitly political film essays by Harun Farocki, May 1st refers to the genre of “direct cinema”, including in the video frame different participants of the events to keep Gluklya’s of view rarely revealed. Through this video recording of a relatively short period of political history we can observe the making of the authoritarian regime, the peak of which we are seeing in today’s Russia. Year by year in the video we observe the growing control of public space and censorship of slogans. If in 2017 the demonstration body is framed by policemen who can adequately communicate with protesters, in 2019 we see different security forces with different uniforms and ammunitions ready to act at any time. The entrance to the last demonstration in 2019 was subject to strict controls, with metal detectors and slogans’ careful examination.

This video documentation showcases the firmed and united artistic political body that has grown in the oppressive regime in some loopholes of freedom: a community of St Petersburg artists, writers, poets, academics, performers and activists marching with banners produced at homes or in studios. Among them representatives of the art groups and pseudo political parties Do Nothing (Ниичегоделать), which questions the necessity of labour in capitalist society and demands a basic income for everybody, and Party of The Dead, that “proposes to their supporters to ‘live with the dead’—a pessimistic interpretation of Russian cosmists who wanted to resurrect the ‘fathers’”.

Together with her friends and collaborators, Gluklya also forms her own Column of Fragility, with costumes and slogans that aims at queering the verticality of power and addressing different pressing political inquiries. Examples of costumes that make up the column are presented outside of the screening dome, including protest art clothes that were produced for other demonstrations and performative actions in different years. Among them, a significant work by Gluklya, that anticipated Melting Snowball, is Clothes for the Demonstration Against False Election of Vladimir Putin (2011-2015) developed during the protests “For Fair Elections” in Russia between 2011 and 2013, which some English media referred to as the “Snow Revolution”. Presented at the 56th Venice Biennale in 2015, the 43 objects “re-created” representatives of protesters with different political positions.

During May 1st in 2017-2019 it was still possible to openly chant “Lies, fear and violence are the basis of the defensive capacity”, “Down with fascism, homophobia and sexism”, “Down the police state”, “My body—my business”, slogans against the decriminalization of domestic abuse, proclamation of female rights and gender equality; there were banners against torture in prison and forced imprisonment of political activists in psychiatric institutions. In today’s Russia for such slogans in the streets or in social media contents one can be accused of extremism and be incarcerated.

During the 2018 demonstration recorded in May 1st philosopher Oxana Timofeeva says that “only being on the verge of madness we can understand the essence of things”. Watching the documentation of these demonstrations from today’s perspective, when Putin’s regime got to the highest level of its madness, we understand that this agony, with the last convulsions of Soviet imperialism, can’t last forever. As they say, the end comes unnoticed: a reminder that can also be found in Alexei Yurchak’s famous book Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More, about paradoxes of the Soviet political project revealed by the peculiar experience of its collapse. Possibly, after the end of the current totalitarianism in Russia, Gluklya’s video documentation of the May 1st demonstrations in St Petersburg will serve as historical record, among many other study materials, documenting the last years of Russian ill and decomposing political regime.

[1] “Inside yurt is a very regulated area with clear division of the space: to the left of the entrance there is the world of men, the right is the female half. The central part is the hearth, behind which is a place for guests of honour. During the wedding, the engaged bride is seated on the male half: she no longer belongs to this family, she is like a guest. In the same way, during the funeral the deceased body is placed on the same part: the dead person is associated with the guest, which, like the bride, leaves the world of the family”.From the correspondence and consultancy with Inga Stasevich, Senior Research Fellow at the Department of Central Asia, Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkamera), St Petersburg.

[2] This and the following quotations in this chapter are from Two Diaries: Gluklya and Murad