Thinking Through Data

Surveillance systems, climate crisis, technological knowledge, contemporary art and practice

It isn’t easy to define or classify Paolo Cirio’s work. He describes himself as an hacktivist, a conceptual media artist and a cultural critic. Indeed he works at the intersection of art, technology and activism, by analyzing and confronting legal, economic, and cultural systems of the information society. Curated by Marco Scotini, the retrospective exhibition Paolo Cirio. Monitoring Control was held at Fondazione Modena Arti Visive and brought together a wide and cohesive selection of works produced by the artist in the last ten years, after his last project Natural Sovereignty, previously exhibited at Certosa S. Giacomo in Capri.

Jacopo De Blasio spoke with the artist about surveillance systems, climate emergency, technological knowledge, contemporary art and practice.

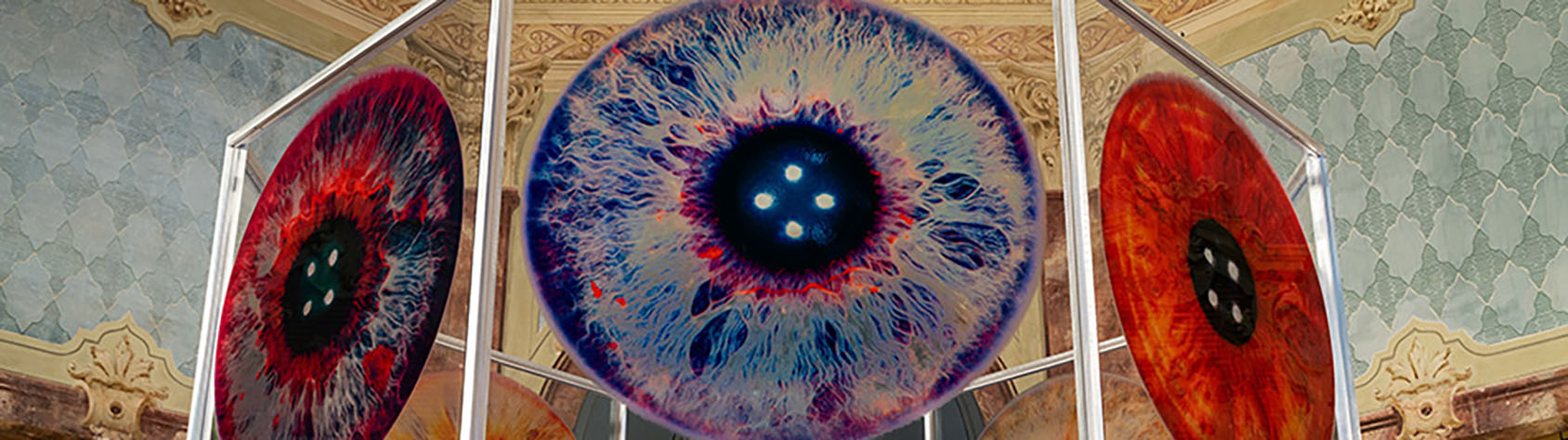

Jacopo De Blasio: Your work Iris is a study for an attack on the biometric identification of irises. Featuring a Panopticon tower with eight prints of modified irises, the installation induces a state of conscious visibility in which both the act of surveilling and being surveilled are a potential within everyone’s reach. Are we living in a contemporary Panopticon?

Paolo Cirio: Iris is my most recent work. It seems just a very aestheticized installation, but it is actually based on my in-depth research about biometrics and iris recognition. Like other works of mine, this is a rigorous investigation on a controversial technology. In this work, form and meaning are merging, the installation takes the shape of a panopticon tower, and for each side there are large prints of irises. Visible from the outside of this octagonal structure, those eyes stare at the public from the inside the tower, while the public can simultaneously look at the eyes looking out and inside. The images are real scans of irises, which were taken to develop this technology. I found thousands of those images of irises used to develop related devices and algorithms. I then made a selection for types of irises, by colors and typical patterns and I ultimately altered the colors and the biometric points that make the iris identifiable.

This work is emblematic of the idea of someone’s power to surveill us from a privileged point of view, and at the same time about the awareness of being surveilled and its induced fear. Yet, it also contemplates the possibility of being able to see how the system works from the inside and eventually accessing the same power structure and point of view. It’s about the multifaceted gaze of today’s technology of vision, a kaleidoscope in which surveillance multiplies its powers, dangers, and potentials in many directions and on many levels. The power asymmetry of the panopticon is reassembled in new symmetries that recombine by looking through it and exploiting it.

In our contemporary society, surveillance has to do with any aspect of our life. We learned how the Internet became such surveillance technology, from a system to communicate, a media, or a tool for finding information. This is something I saw happening during the past twenty years of working with the Internet, and how it changed—something I used in several works of mine over the years. Today, I think we are approaching the next level of ubiquitous surveillance, which is the surveillance of our physical body, organs, flesh, and fluids, everything we are made of. This is what already happens with facial recognition and with all those technologies in the field of biometrics. Recently, I’ve also done a video interactive installation titled Bodily with a thermal camera, for addressing body scanners that don’t just profile people, but can also identify our health conditions and emotional state, opening up this technology for very concerning forms of discriminations and control, from which is very hard to hide, since these devices can scan bodies from far away, even behind walls.

Speaking of iris recognition as one of the most accurate forms of biometric identification, I’m particularly looking at the case of India, where the government scanned and identified over one billion people’s irises. Then, inevitably a huge leak of all that biometric data happened, and personal data were compromised forever. You can’t really change biometric data the way you change a password, once they are leaked, anyone can use it to identify you or to steal your identity. Biometric identification is often used by governments not just to surveil the population, but also to control access to public services—and where several types of abuses can take place, such as profiling and discrimination enacted by the government, private firms, or any other bad actor.

So, yes, we are living in a dangerous contemporary Panopticon from which is very hard to escape and hide and we are getting into a much creepier one, something we are already seeing somehow with the Covid pandemic. Now the technology looks at our body and to connect data about our health, medications, mental state, emotional feelings and financial status, according to which we can access a public service or not. Everything seems to converge together. It’s actually a pretty sad picture we’re looking at. That’s why it’s important to fight back with any form of regulations or bans of such use of technology. Something I’ve done with a few projects, running campaigns and even drafting privacy policies, such as the Right to Remove in the United States. The one to Ban Facial Recognition in Europe has been particularly successful in terms of partnerships and number of signatures. I like it better than waiting for dystopia and writing about dark futures—waiting for fascism to come rather than fighting it. That type of choice is something I discuss as the ethics of the esthetics of information ethics.

Should politics of education take an interdisciplinary and critical approach to improve technological awareness, by developing literate practices?

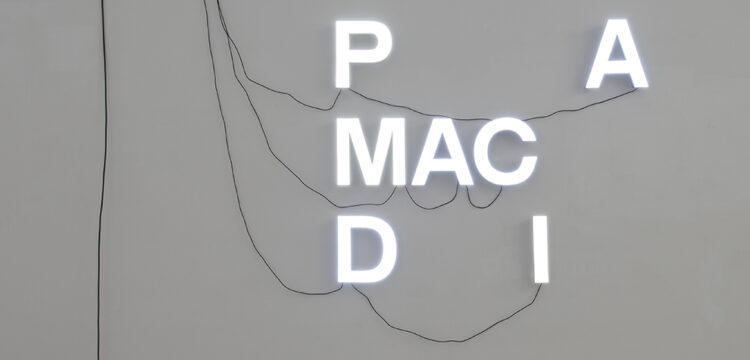

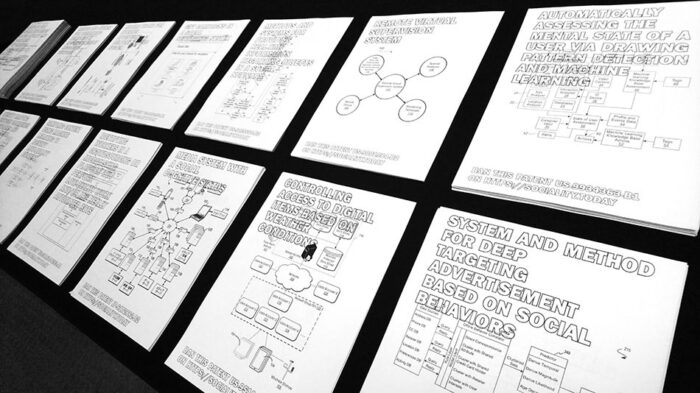

Well, this is somehow related to Iris, at least to the physical installation. It’s the way you walk in and out the panoptic tower. By awareness or technological education I mean that you can actually be inside a counter-tower of counter-surveillance. We must learn ways to monitor and decode surveillance systems. At the same time, there is a lot to learn about those systems, which are often not transparent or known at all. We definitely need alternative forms of education, which should be interdisciplinary. Art has been very useful so far. Well, although there are many other artists involved in this, some projects of mine are supposed to warn about the dangers of these systems, in a quasi didactic way. It must be said that education is not about technology itself. For instance, I do have this project called Sociality, which documents over twenty-thousand patents of socially manipulative technology, and it’s actually about understanding the consequences of such technology and what it produces in our lives—and in the political sphere too. That’s kind of missing when we talk about education. There are teachers in our schools that teach how to use computers, who might even try to mention the potential dangers, but there is something much deeper and profound that should be taught, about the very understanding of what these media and technology are capable of at this point. You can teach how to detect fake news or how to deconstruct Instagram influencers, how not to share private information on social media.

What really scares me, for instance, is the decentralization of the Internet. The excitement about it reminds me how people were naïve about social media ten years ago or so, and its potential for democracy and society. That didn’t teach us enough about future dangers of abuse of power in network environments. It’s already happening and it really scares me, because the question now becomes: who’s going to teach us how to fully navigate an unregulated information space, like Blockchain or even just a messaging app, like Telegram? I think it’s important to learn how to understand those technological things in relation to the very formation and fabrics of our society and how to be one-step ahead. Simply, there should be education about a global democracy that has agency over those tools, rather than focusing on the tools themselves.

Your projects are always well formulated, both technically and conceptually. Do you think this is necessary to avoid contemporary art’s tendency towards self-referentiality? Should contemporary art look beyond the—kind of obsolete—distinction between passive and active spectators, in order to create social change, by attempting to sensitize and engage the public outside the “art space”?

Even before I was an artist and when I started, I used to go to art galleries and I was very critical of what I was seeing. At the same time, I didn’t feel I was just an artist, but also an activist along with some sort of journalistic work. Yet, I loved art, so I thought I could do something different, hoping to even change that culture of art I didn’t agree with. In my mind, art could be a medium to communicate my ideas and provoke changes about issues that were relevant to me. That’s why my works try to be informative. There is no abstraction, and they’re actively aiming at change in the way they make people aware of some specific subjects.

My works and my writings involve complex planning for reaching wider audiences, treating certain topics and proposing solutions to solve issues. At the same time, I also employ artistic language, although it is sometimes limited and self-referential, that’s the device I prefer to define my work—since it is neither simply activism, journalism, technological research or hacking. For a long time I had to fight against the idea that my work was mainly activism—a few years ago this was a taboo, while now it is one of the main trends in the art world, despite it being still mainly “art-washing” with no authenticity. It was also hard to have my efforts recognized, as we live in a self-referential art world and in a cultural hegemony, where you should have a degree from the US or UK to be taken into consideration. I had to decode how art is valued, something I’ve done with both projects Art Commodities and Art Derivatives, where I broke apart the value production chain, in the form of institution critique, a hack, and new proposals for a more fair, democratic and transparent system of values within the art world.

Yet, the only satisfaction I get, usually it’s from the audience outside of the self-referential art world. When I have people coming to me and appreciating what I do for what it really means or it has done, that’s better than any museum show I can have.

Does the physical translation of contemporary digital art suffer from the limitation of the exhibition format? In that sense, what is the role of the often-abstract representation of the web?

Well, I see limitations from all sides to be honest. I think digital art, or rather Internet art, is definitely limited when it comes to the exhibition space, because there is no interaction on the same level of experience, there is never the same amount of material that can provide information and participation for everyone. Nonetheless, I’d say digital art is very limited when it’s just something to display on a screen. It doesn’t translate the material aesthetic of art, and it’s hard to engage with. For instance, I think there is a huge lack of attention toward the screen at this point. It is not easy to bring an audience to a website. Now even a purely digital art project on a big online platform, doesn’t really get much audience, and even less interaction with it. When the same thing is printed out and put on a wall—when people can walk through these works as a physical experience—that becomes way more powerful, as everyone is so tired of the screen. That’s why I enjoy having gallery and museum exhibitions. At the same time, I enjoy making things and designing the installation and creating environments. Keeping things digital is actually much harder these days, especially with projects made of millions of pictures and data records that have to be shown on custom made interfaces, where participation needs to be recorded. It is getting difficult to maintain these works digitally.

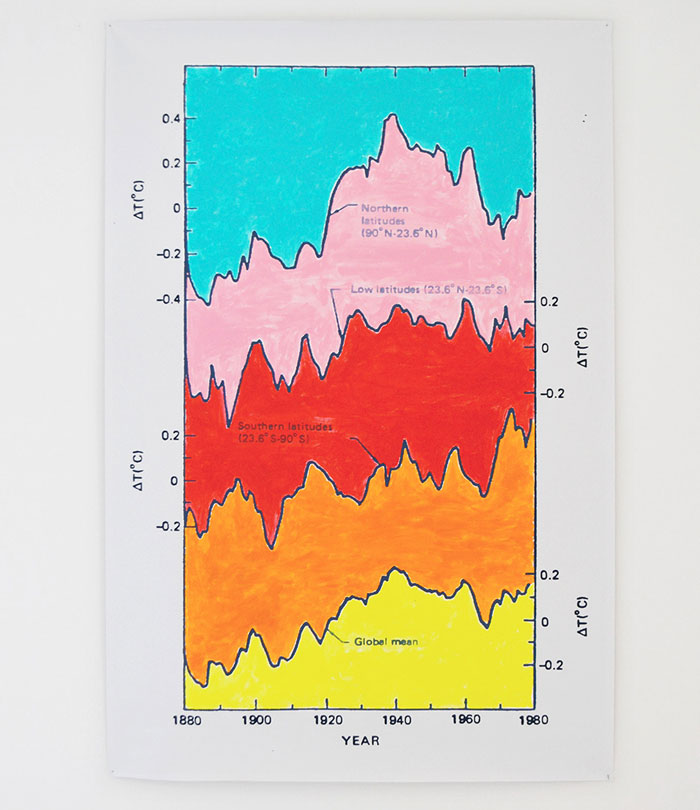

Natural Sovereignity presents a utopian vision of climate justice. What could be the role of social networks in this “Climate Crime tribunal”? Is there a connection between technology and climate change? Do you think art and technology can, or perhaps should, make them visible and tangible?

The Climate Tribunal is also about technology to some degree. I do use big data, for instance with the project Extinction Claims, I composed a huge database of over 40000 species that are at risk of extinction, and then I coded an algorithm, which calculates the financial compensation for each species. Although I use technology, I’ve become so hopeless about social networks: I don’t really know if there is actually a right way to use it, especially when speaking of climate crisis, because is no longer a matter of rising awareness, but rather about who has agency to change the perception of this reparation emergency, who needs to be brought to justice to be held accountable. When you mention the role of social networks, I have to think about the large amount of money that was paid by fossil fuel firms to Google or Facebook to actually spread misinformation about climate change.

Beside technology, this series of the Climate Tribunal points out an approach and an aesthetic that I already used in former projects to talk about political or financial issues. The thread here is more on the “evidence aesthetics”, and eventually a “secrecy aesthetics”. In this Climate Tribunal, there are a few works about secrecy, documents about studies in climate change that were kept secret for decades. Also in the work I’ve done about the Cayman Islands, Loophole for All, wherein I revealed over 200000 Cayman island companies hidden behind the financial secrecy of the Cayman government.

For instance, again in Sociality, I put together a huge collection of unknown documents, that were hidden behind complexity and quantity. This “evidence aesthetics”, which I often translate also in physical objects, has something different compared to documentary art: I show documents, while I actually try to encourage public agency. Sometimes these documents’ role is just informative, whilst in evidentiary aesthetics the document enacts the juridical function of bringing the evidence in front of a jury or a tribunal, in front of someone who is supposed to bring justice. In my work, those documents become active by engaging with the audience, by being at their disposal. For instance, those thousands of pieces of evidence about species threatened with extinction aren’t just data points or pictures: I invite everyone to take those legal claims and submit them in courts and appropriate governmental agencies.

In a 2011 interview you defined money as “Pure Information”. Do you think its role has changed over the past decade?

I do think it’s still as such, but actually today money is pure data. I don’t think information and data are the same thing, but because of crypto and fin-tech, now money has become such a small unit in amount and speed, that we can call it pure data. In 2011 Bitcoin was already around, it was just the beginning, but from 2011 until now, the common idea and the perception of money definitely have changed a lot. Crypto-finance today is really widespread. Nevertheless, in the past year we have also seen how artworks became pure data, if we think about NFTs. These are definitely the reduction of a whatever discipline to pure data—there is nothing exciting about it. One thing is to make artworks with data; another is to reduce the field to pure data. It’s just really depressing to talk about NFTs and Crypto-art during a pandemic and a climate crisis. It seems really out of context.

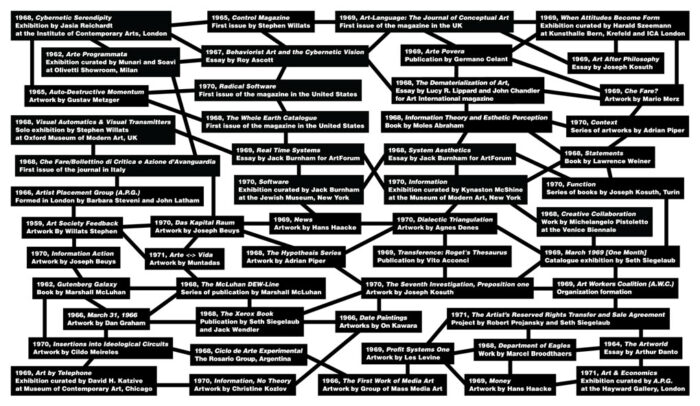

You have mentioned Gustav Metzger in your past diagrams series. Do your projects also deal with self-destruction, even if in a different way, or it was more about his interest in technology?

I mentioned him because it was mostly a project about art history, titled Foundation, and Metzger has been one of the first artists in the sixties to get interested in the growing relationship between art, technology and social issues, which is still relevant today. I don’t think my works are self-destructive, however some of them will eventually self-destruct, since they are very controversial or even too illegal to be shown. They will vanish also because Internet interactions are ephemeral and the technology is constantly changing.

Would you still define yourself as a “Tactical Media Artist”?

No longer no. I mean, it’s definitely part of my background, but today I’m also engaged in making these fine artworks and in researching art history and aesthetics. I perceive tactical media as a technique to provoke through technology, and that’s something that I do although it is just a set of tools. I’d rather expand this idea to another level. That’s why for instance I wrote about evidentiary art, regulatory art and some other concepts I’m developing. Maybe once I used to be a tactical media artist, and now I moved to something else.