Them, Kathy Acker

A comprehensive collection and reflection around the work of the acclaimed American writer

I, I, I, I, I, I, I, Kathy Acker is an exhibition and series of talks, discussion groups, performances and screenings built around the written, spoken and performed work of American writer Kathy Acker (1947–1997). The exhibition is accompanied by a small guide that offers an extensive insight also on her literary timeline.The guide is reprinted in full below (copyright ICA, London).

Acker is an exceptional figure in late-20th-century Western literature who moved between the avant-garde art and literary scenes of New York, San Diego, San Francisco, Seattle, Paris and London. Through her prolific writing, Acker developed experimental textual methodologies as she distorted language, hybridised fiction and autobiography, ‘plagiarised’ the work of other authors, and introduced maps, drawings and diagrams.

For Acker, the use of the first-person singular was, in fact, plural, as she utilised the ‘I’ in her writing to inhabit different identities from her own life, fiction and history, acknowledging her complicated relationships with family, friends and lovers. Acker’s work addressed language as a site of contestation from which meaning and identity are both constructed and splintered. She provocatively confronted the strained relationship between desire and reality within culture, sex, patriarchy, the body, war, money, the family, mythology, colonialism, sickness, and the city in ways that remain critically relevant to our current times.

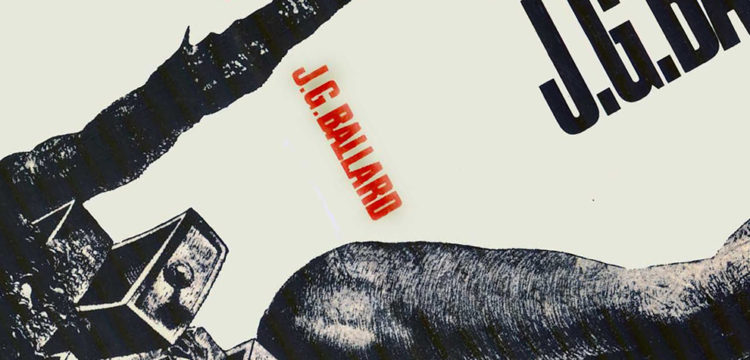

Kathy Acker, Blood and Guts in High School, 1978 (p88, 89). Courtesy the estate of Kathy Acker

Acker’s output as a writer spans from the late 1960s to her death in 1997. Her early writing positioned her within an experimental literary scene that emphasised disjunction and the materiality of language. The performance of the written word – particularly at readings held at New York’s downtown arts venues – formed a significant part of Acker’s practice, which included collaborations with musicians on live performances and recordings, and with artists and filmmakers on films and video works. As Acker’s work shifted from poetry to primarily prose, she was influenced particularly by the cut-up works of William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin, while drawing directly from diverse literary sources including Georges Bataille, Charles Dickens, Marguerite Duras, Euripides, Arthur Rimbaud, and the Marquis de Sade, as well as pulp detective and pornographic novels. From Rip-Off Red, Girl Detective (written in the early 1970s and published posthumously in 2002) to Eurydice in the Underworld (published in 1997) Acker wrote over twenty published books, contributed numerous texts and essays to journals and magazines, and wrote four works for the stage. During her time living in London between 1983 and 1989, Acker became a notable figure within public discourse, appearing on television and becoming a regular contributor to talks and events at the ICA.

Installation view of I, I, I, I, I, I, I, Kathy Acker at ICA, 2019. Photo Tomas Rydin.

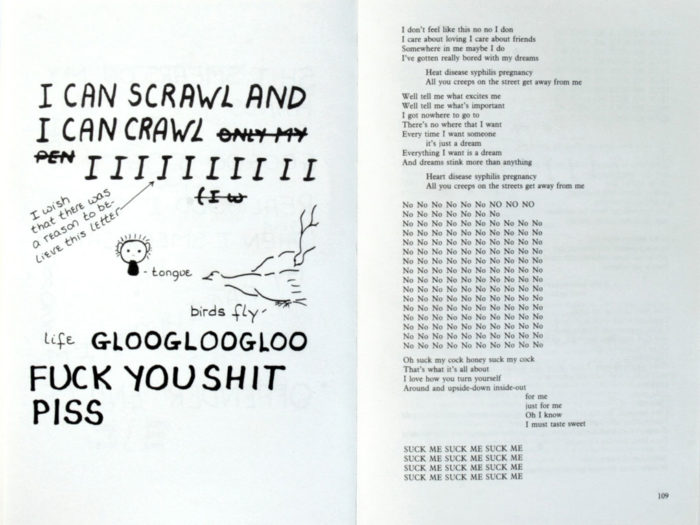

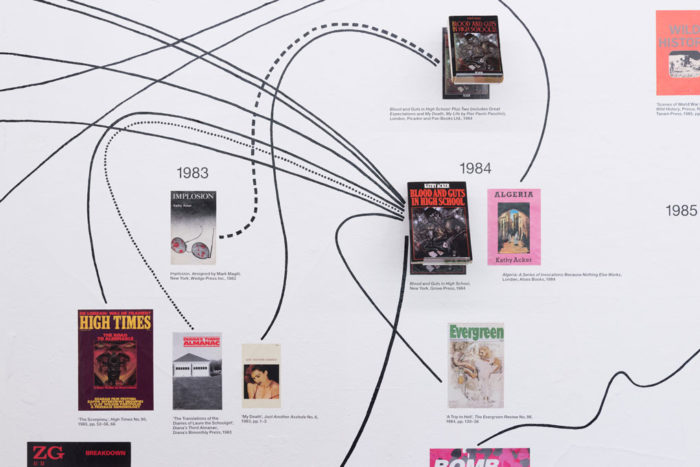

I, I, I, I, I, I, I, Kathy Acker begins with a timeline of Acker’s published works, offering an insight into the layered ways in which Acker approached the circulation of her writing; at times self-publishing and self-distributing, as well as re-versioning texts as they appeared in different magazines and journals and as sections within her novels. Acker’s writing emphasised a form of montage, with her books often reading as composites of disparate texts. Acker saw this textual fragmentation as linked to the deconstruction of identity and meaning, a position that evolved in her later books into a more topological and layered movement of identities and narratives.

Reflecting this aesthetic tendency, the exhibition isolates fragments from eight of Acker’s key novels, creating a serial structure further emphasised by a dense exhibition architecture. In a text published in 1996 as the foreword to Samuel Delany’s novel Trouble on Triton, Acker wrote: ‘… a name doesn’t tell you what something is so much as it connects the phenomenon/idea to something else … In this sense, language is the accumulation of connections where there were no such connections.’ The exhibition builds on this understanding through materials presented in proximity to the fragments of Acker’s writing that open onto a web of affinities and dialogues.

Installation view of I, I, I, I, I, I, I, Kathy Acker at ICA, 2019. Photo Tomas Rydin.

Central to this connective web, the exhibition presents works by other artists and writers, both those working during Acker’s lifetime and those active today. While not necessarily referencing Acker’s work directly, nor produced with her in mind, these artworks offer points of connection and resistance to Acker’s linguistic strategies and lines of thought. Alongside these works, the exhibition presents materials including video and audio documentation of Acker’s performative appearances in various cultural and media contexts, and selected documents and books from her archive and library. Acker was a voracious reader, and six thousand of her books are now held at the University of Cologne, serving as a meta-text for the references and influences around which she built her writing.

Rather than aspiring to be a comprehensive historical survey of Acker’s prolific output and life, I, I, I, I, I, I, I, Kathy Acker considers the methodologies and concerns within her writing and identity as unresolved forces which extended into multiple artworks, documents and media objects during her lifetime, and have continued to unfold directly and indirectly through the work of other artists and writers after her death. The fragments of Acker’s writing presented on the exhibition walls are taken as engines for the generation of new relations, ideas and possibilities, underpinned by Acker’s fervent inquiries into identity, gender, and the self under late capitalism.

Installation view of I, I, I, I, I, I, I, Kathy Acker at ICA, 2019. Photo Tomas Rydin.

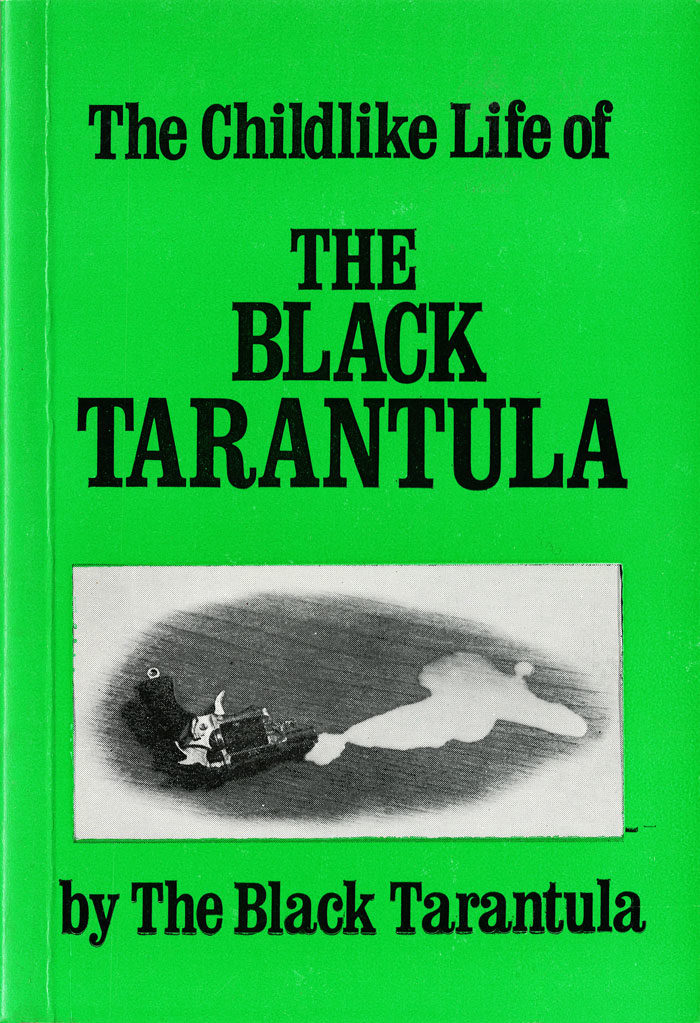

I. from The Childlike Life of the Black Tarantula by the Black Tarantula (1973)

The Childlike Life of the Black Tarantula, written under the pseudonym The Black Tarantula, was first self-published serially in six parts and distributed by Acker using a mailing list borrowed from the artist Eleanor Antin. Each of the texts adopts a similar structure, with appropriated biographical chronicles – ranging from those of 19th-century murderesses to William Butler Yeats and the Marquis de Sade, to fragments of novels by Violette Leduc and Alexander Trocchi – folded into Acker’s autobiographical writings and diary entries. As Acker stated in a 1989–1990 interview: ‘I was splitting the I into false and true I’s and I just wanted to see if this false I was more or less real than the true I, what are the reality levels between false and true and how it works.’

‘The story of my life’ introduces themes that recur throughout Acker’s novels and texts: the narrative of her childhood within a relatively privileged family, her troubled relationship with her mother, and the conflict between desire and the mechanisms of societal control. The figures of the prison and the asylum – represented in the text by the literal spaces of the Château de Vincennes and Charenton where de Sade was held in the late 18th century, and the metaphorical spaces of the mind – are echoed in Acker’s characterisations of a 1970s United States defined by the worship of money and an underlying schizophrenia. Through de Sade, Acker parallels the fracturing of identity and the self with the systematic pursuit of desire and progressive steps away from ‘normality’. Acker’s conceptual approach to plagiarising and reconstituting existing texts – while exaggerating breakdowns in language and grammatical structure – echoes this dynamic.

In 1975, Acker contributed to a colloquium at Columbia University titled ‘Schizo-Culture’, and a related issue of the journal Semiotext(e) in 1978. The colloquium concretised an intersection between American cultural politics, the anti-psychiatry movement, and the philosophy of figures such as Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. ‘Schizo-Culture’ explored what Semiotext(e) founder Sylvère Lotringer described as ‘the process by which social controls of all kinds, endlessly re-imposed by capitalism, are broken up and opened to revolutionary change.’

Kathy Acker, The Childlike Life of The Black Tarantula by The Black Tarantula. TVRT and Printed Matter, New York, 1978. Copyright Kathy Acker 1973

II. from Blood and Guts in High School (1984)

Blood and Guts in High School is perhaps Acker’s most celebrated book, and in many ways her most fragmented. It is composed of a collage of materials produced by Acker between the early 1970s and 1978, including poems, fairytales, dialogic prose, drawings, maps and a section of poetic ‘translations’ from Farsi to English titled ‘The Persian Poems’. The through line within the book is the narrative of Janey, a 10-year-old girl living with her father, whom she regards ‘as boyfriend, brother, sister, money, amusement’. Janey moves to New York City, is raped by two men, and is sold to a slave trader. Shocking in its depiction of sexual violence and exploitation, the book casts these events within nuanced dynamics of power, dependency and desire.

Acker’s pictographic ‘dream maps’ originally existed as large-scale drawings. Within the context of Blood and Guts in High School, they appear as Xeroxed reproductions across several pages, entering the space of Janey’s narrative, although it remains ambiguous as to whose dreams they represent. These maps spatialise a childlike unconscious dominated by an excess of psychosexual symbolism and the movement between zones of fear and natural and spiritual idyll. In Dream Map 2, the phallic figure of a ‘huge jellyfish worm’ dominates alongside the vision of a father-like ‘baba’; underlying the drawing is a spectre of sexual violence and looming death.

Within the map, Acker collapses numerous cultural and mystical references including Haitian voodoo, Greek mythology, the 1959 French-Brazilian film Black Orpheus, Kabbalah, and the yogic teachings of Swami Muktananda. The descriptions of colour which thread through the map stem from Muktananda’s writings on the body as a lotus flower with petals of four colours (red, depicting the ‘gross body’; white, the ‘subtle body’ in which we experience sleep and dreams; black, the ‘causal body’; and blue, the ‘supracausal body’, the foundation of the ‘highest inner vision’). Voodoo – particularly the belief in spirit possession – plays a recurring role in Acker’s writing and thinking around animism and the human body, seen most prominently in her later novels. The instrument of the map also features widely in Acker’s work, marking other-worldly journeys, as well as the concept of ‘mapping’ as linked to forms of colonial and territorial control.

Installation view of I, I, I, I, I, I, I, Kathy Acker at ICA, 2019. Photo Tomas Rydin.

III. from Great Expectations (1982)

Acker’s Great Expectations brazenly steals its title from Charles Dickens’ novel of the same name. From the book’s first chapter, titled ‘Plagiarism’, the reader is left in no doubt of Acker’s intentions, as she makes use of existing texts and overrides principles of artistic property. Though the first few lines of the novel are a virtual facsimile of the original, Acker’s Great Expectations bears little resemblance to Dickens’ classic. Acker essentially inhabits the cultural shell of Dickens’ novel, inserting texts from an array of writers, from the Augustan elegiac poet Sextus Propertius to controversial French writers Pierre Guyotat and Anne Desclos (writing as Pauline Réage). As Acker once stated, this methodology of ‘stealing’ drew directly from a sense of abject subjectivity: ‘I was unspeakable, so I ran into the language of others.’

In this extract, Acker constructs a jarring movement between personal reflections on family and childhood and the violence of war. Working from a French-language edition of Guyotat’s 1970 Eden, Eden, Eden (the writer’s response to his enlistment in the Algerian War), Acker’s translations of the author’s experimental flows of sex, raw materiality and violence are shocking and confrontational. Through her juxtaposition of these viscerally nightmarish scenes with those of familial love and affection, Acker affects a struggle between the conscious and subconscious, between ‘repression’ and ‘materiality’. The result is a disjointed structure, exemplary of Acker’s approach to collage and appropriation, used to disorientate the reader and provoke conflicting emotional responses.

Acker ambiguously weaves her biography through Great Expectations. The biography of Peter (Pip) is paralleled with her own, as she recounts the suicide of her mother and the death of her grandmother in the book’s opening paragraphs; Dickens’ orphaned Pip providing a convenient guise for Acker to inhabit. This passage harbours grief and questions of forgiveness, while deconstructing the dysfunctional nature of familial desire. The dissection of the institution of the family – alongside other institutional systems, such as the school or the prison – remain consistent throughout Acker’s work. The personal revelations in Great Expectations bind the reader to a notion of the self immersed in dichotomies of truth and illusion.

Kathy Acker and The Mekons live at Freedom, London, 29 March 1996. Digital Transfer from Hi8 video. Courtesy of Stuart Curley.

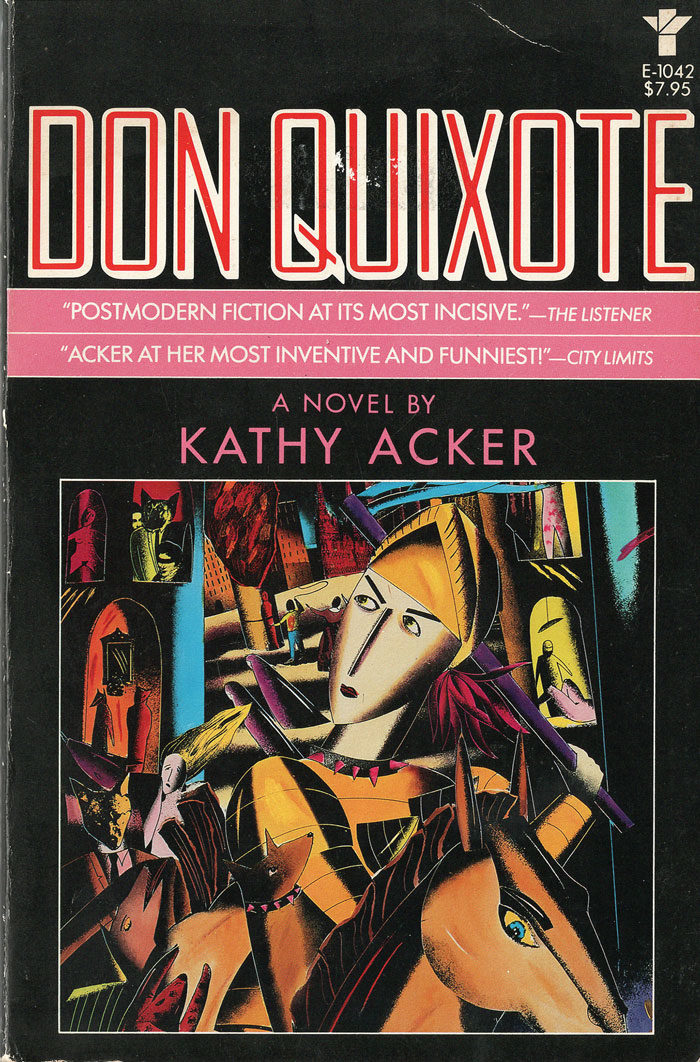

IV. from Don Quixote: Which Was a Dream (1986)

‘I’m finishing a novel about Don Quixote. About a woman who becomes a knight by having an abortion’, says Kathy Acker in a short interview in City Limits, speaking about her 1985 play Lulu Unchained, which was performed at the ICA. Cribbing German dramatist Frank Wedekind’s ‘Lulu’ plays from the turn of the 20th century, Acker later incorporated the scripts into her novel Don Quixote: Which Was a Dream (1986) published two years after settling in London from New York.

Hijacking Spanish author Miguel de Cervantes’ 1605 Don Quixote, Acker empties out the 17th-century novel about a self-styled knight on the brink of insanity, replacing the protagonist with a female and charting a contemporary terrain concerned with issues of gender, madness and society, as influenced by prominent texts by late-20th-century French philosophers, including Michel Foucault’s Madness and Civilisation: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason (1961) and Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (1972).

Kathy Acker, Don Quixote, Grove Press, New York, 1986, first edition. Copyright Kathy Acker, 1986.

‘BEING DEAD, DON QUIXOTE COULD NO LONGER SPEAK. BEING BORN INTO AND PART OF A MALE WORLD, SHE HAD NO SPEECH OF HER OWN. ALL SHE COULD DO WAS READ MALE TEXTS WHICH WEREN’T HERS’, reads a section break in Acker’s Don Quixote. In defiance of the Western literary canon – historically dominated by male writers – Acker appropriates sections and structures from a variety of sources to weave a narrative that explores the illusion and construction of identity.

In this passage, Acker draws into focus both the Oedipus and Electra complexes (theorised by psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud to describe the conflicting impulses of attraction and rejection experienced by adolescents toward their parents). In Don Quixote: Which Was a Dream, Acker’s protagonist is several times removed from the society in which she lives, concealed beneath layers of language, costume and expectations. By establishing Don Quixote’s character as detached from society, Acker challenges the common acceptance of ‘madness’, defining the condition as a refusal to conform to societal expectations.

Installation view of I, I, I, I, I, I, I, Kathy Acker at ICA, 2019. Photo Tomas Rydin.

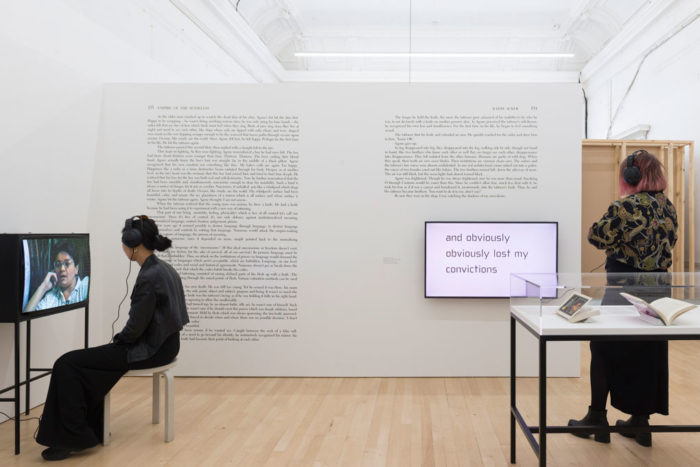

V. from Empire of the Senseless (1988)

Empire of the Senseless is one of Acker’s most controversial and challenging novels for its uncompromising entanglement with postcolonial discourse. Utilising and repurposing the often violent language of imperialism, Acker toys with the moral implications of reinvigorating offensive terminology in an attempt to use language as an emancipatory tool.

Set in a speculative near-future Paris, the narrative describes the fallout of an Algerian rebel occupation, obliquely acknowledging both Algeria’s occupation by France and the United States occupation and French rule of Haiti. The novel concerns Thivai, a pirate, and the part-robot, part-human Abhor, who each represent the violence of capitalism on the individual through their shared rejection of the repressive system in which they find themselves.

Acker dedicates Empire of the Senseless to her tattooist, a tribute that emphasises her view of the body as a site of reclamation. At the time of writing, many women were embracing forms of body modification as a means of liberation alongside evolving ideas about female beauty and sexuality. Acker’s body was a site of personal affirmation; through her bodybuilding, tattooing and piercing, she exercised control against the afflictions of dominant society. In Empire of the Senseless, bodies become the site of politics to the extreme. From zombies to sex objects presided over by the symbolic father of commerce and exploitation, the bodies of the novel exist both as concrete entities and as constructions produced by discourse, societal values and labour.

Splicing together texts by science fiction writer William Gibson with the novels of Mark Twain and others, Acker plagiarises and paraphrases to form a loose narrative arc. Returning to the subjects of previous work, including Algeria: A Series of Invocations Because Nothing Else Works (1984) and Kathy Goes to Haiti (1978), Acker mixes the personal, political and spiritual in a complex terrain that mirrors the present via a thinly veiled allegory.

Kathy Acker, In Memoriam to Identity, Grove Weidenfeld, New York, 1990 first edition. Copyright Kathy Acker, 1990

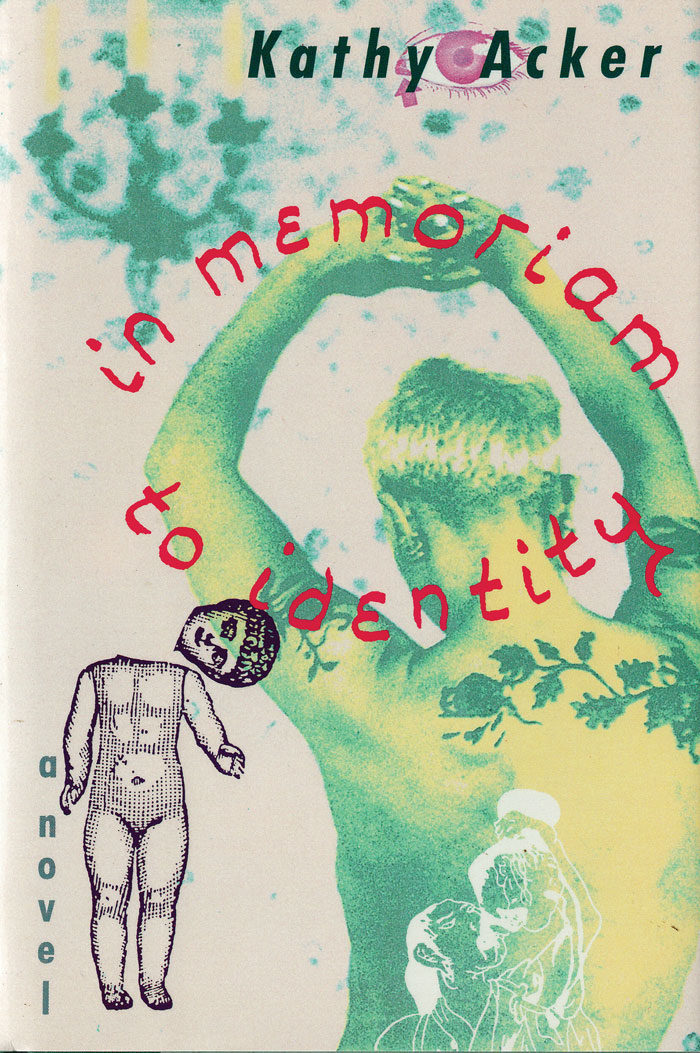

VI. from In Memoriam to Identity (1990)

Alongside Empire of the Senseless, In Memoriam to Identity marks a shift from the deconstructed ‘I’ of Acker’s early novels to a notion of identity enfolded in intersecting narratives – what scholar Georgina Colby has called a ‘protean self’. The book exists in four parts: the first, a rewriting of the biography, letters and poems of 19th-century poet Arthur Rimbaud, containing re-worked illustrations by Japanese ukiyo-e artist Tsukioka Yoshitoshi and passages from Murasaki Shikibu’s 11th-century novel The Tale of Genji; and the latter three, partial narratives from the writings and life of early-20th-century novelist William Faulkner, recast around two female characters named Airplane and Capitol.

The act of naming in In Memoriam is slippery: Rimbaud moves across literary spheres into the world of Faulkner, first becoming ‘R’, the partner and rapist of Airplane, and then later reappearing as ‘Rimbaud’, the brother of Capitol. In the latter part of the book, Acker reformulates Rimbaud’s infamous declaration made in a letter written at age sixteen, ‘I is another’: Rimbaud had said: ‘I am an other.’ Airplane: ‘But Rimbaud wasn’t a woman. Perhaps there is no other to be and that’s where I’m going.’ This reformulation suggests Acker’s move from a distanced notion of the ‘I’ to a sense of ‘owning’ otherness, proposing a feminist ‘non-identity’ as a destination.

Kathy Acker in conversation with Angela McRobbie at the ICA, 1987. Copyright ICA, London.

In ‘The End of Poetry’, Acker draws on the lineage of the poète maudit – the artist living life outside and against society – exemplified by Rimbaud. The passage begins as a rewriting of the symbolist poet’s 1873 A Season in Hell, with Acker’s insertions framing a space in which ‘language and the flesh are not separate’.

This ‘language of the body’ and sexuality is one that, in interviews, Acker cited as ‘an undeniable materiality [that] you can return to…’ when ‘… the meanings associated with reality [are] up for grabs.’ In inhabiting the story of Rimbaud, Acker articulates the imperative that ‘The imagination is nothing unless it is made actual.’ This line marks the end of the first part of In Memoriam, and in Rimbaud’s biography, the point at which, after being shot by his lover Verlaine, he gave up writing and turned to trading arms and coffee in Yemen and Ethiopia. Acker’s distaste for this turn away from a life of the imagination to life as a colonial capitalist is evident in the insertion of Rimbaud in different guises in the latter sections of In Memoriam as a ‘dead poet’, rapist and businessman.

Installation view of I, I, I, I, I, I, I, Kathy Acker at ICA, 2019. Photo Tomas Rydin.

VII. from My Mother: Demonology (1993)

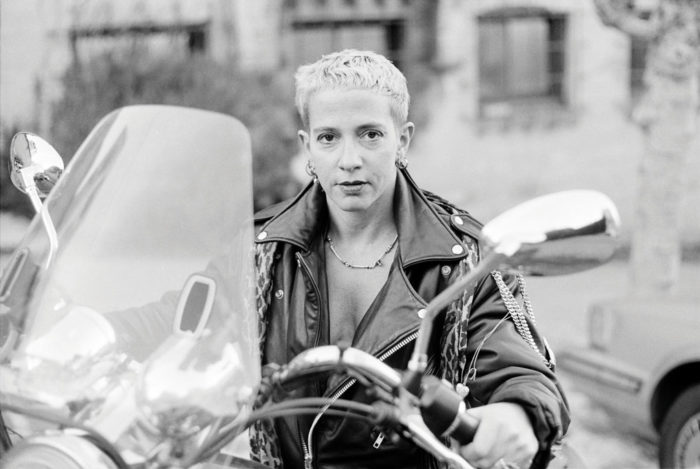

The protagonist of Acker’s My Mother: Demonology is Laure (the pen name of French writer Colette Peignot, 1903–1938). As narrator, Laure journeys through a dark fictional autobiography, detailing early childhood abuse at home, hallucinatory dreams in a girls’ boarding school, and motorbike journeys as a grown bohemian. Having read Laure’s collected writings, which touch on mysticism, eroticism, sexual abuse and revolutionary, Dionysian activities, Acker drew on the writer’s explorations of bodily abjection as fertile ground for her own fiction.

A clear criticism of the oppression caused by heteropatriarchal capitalism, this extract depicts a male-dominated city-scape in which a woman’s body is deemed the status of merchandise and figured as an object of abuse. Raising questions regarding representations of violence and horror in culture, the Father’s rationalisation of the need to paint himself killing his daughter chimes with Acker’s intrigue in the extent to which society is numbed to violence via its omnipresence, and how this is translated into both excess and constraint in art. The figure of the girl who is to be burnt can be described as ‘abjectified’. That is, her bodily otherness disturbs conventional patriarchal notions of identity, while simultaneously establishing a sense of validation for the dominant male characters. Such marginalised ‘others’ populate all of Acker’s writings, as she frequently inhabits ‘I’s’ typically abjectifed for their ‘disturbance’ of normative codes: children, criminals, sex workers, bikers.

With this text, Acker foregrounds the rampant cultural gentrification, commercialisation and resulting violence that afflict contemporary cosmopolitan cities. Rats and zombified real estate litter neighbourhoods cast-off before they were even built. Dead and murdered female bodies also rampage through the novel. Rather than appearing as invisible entities, however, Acker’s corpses are contested sites through which power struggles play out. Writing on the concept of abjection, Julia Kristeva theorises that normative patriarchal sociality is dependent on the expulsion of ‘unclean’ bodily elements – ejaculate, period blood, rotting innards – in order to inscribe civil codes. In contrast, Acker brings such social taboos riotously to the fore, relentlessly confronting corporeal reality in a manner that challenges convention.

Kathy Acker, Pussy, King of the Pirates, 1996. Grove Press, New York, 1996, first paperback edition. Copyright Kathy Acker, 1996.

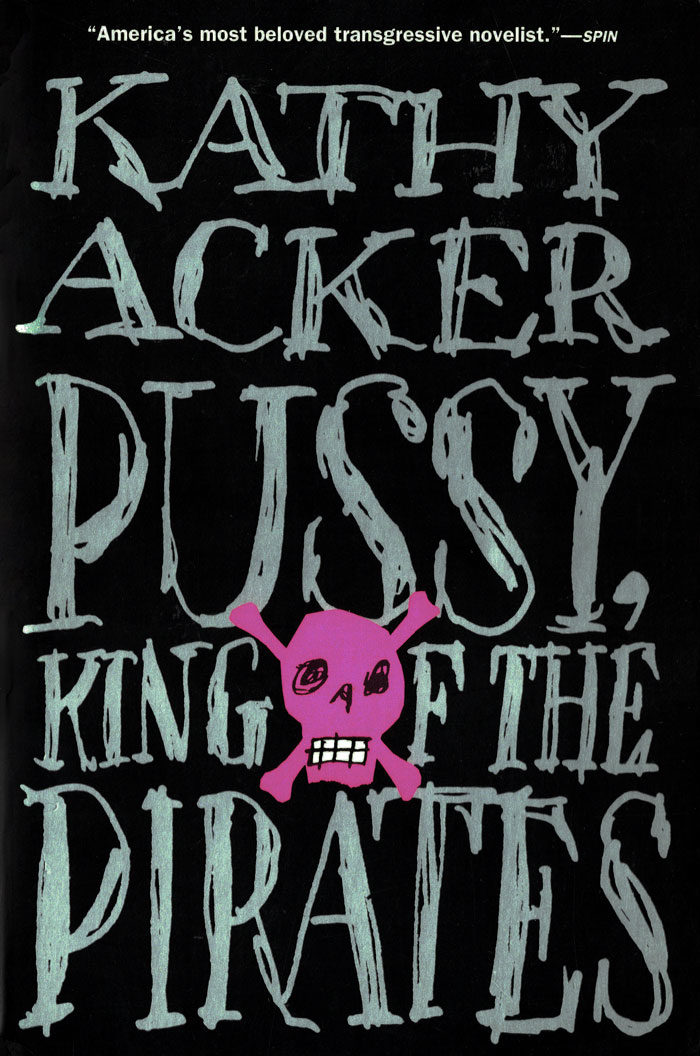

VIII. from Pussy, King of the Pirates (1996)

Pussy, King of the Pirates sees a girl gang of prostitutes and pirates journey from a ‘whorehouse’ in Alexandria, to Brighton, to a ship bound for Treasure Island, before finally arriving in an oneiric ‘land of the dead’. This late novel by Acker focuses on the radical potential of female desire; her characters display a full-blooded resistance to the attempted repression or denial of their desires. Excessive outpourings of sex and mythologising overwhelm the novel, hindering the possibility of a coherent, linear narrative. Rather than simply deconstructing the fate of women’s bodies under patriarchy, this novel also offers a feminist strategy for being-in-the-world.

Influenced by the sex-positive feminists active in San Francisco in the 1980s and 90s (typified by the publication On Our Backs and the lesbian-feminist BDSM organisation Samois), the scene depicted in this extract details the metamorphosis of Pussy and Ange into rats, whose ‘world is ruled by pleasure’. In this sensual anti-discourse, Acker celebrates active desire and sexual corporeality. Foreshadowing many contemporary feminisms which reel against essentialist naturalisms, Acker’s characters exhibit an ambivalence towards the ‘skanky-skunk-wood-tangled-garbage-whatever-it-was called nature’.

Portrait of Kathy Acker, San Francisco, 1991. Photo Kathy Brew.

Acker appropriates classical mythological figures throughout her work, and the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, a recurring narrative, serves as a metaphor for the phallic gaze and death. In one of her last texts, the long-form poem Eurydice in the Underworld, Acker re-enacts the Eurydice myth – based on the objectification of a woman – as a way through which to dramatise her own relationship with cancer.

By foregrounding outside perspectives and experiences, Acker’s methodology functions as a viral critique. Those who are marginalised by the normative systems of power they inhabit (‘whores’, ‘pirates’) in turn infect those very systems by overrunning them with their abject bodies and immutable desires. Acker’s Pussy, King of the Pirates is infested with uncontrollable and fluid bodies which derail singular identities, presenting an anarchic threat to patriarchal norms.