Theaters Of Bodies

Fiction, Reality, Different Selves. An excerpt from the book “L’Ano Solare”

L’Ano Solare. A year-long programme on sex and self-display is the outcome of a research—developed by Il Colorificio—on sexuality, performativity, and self-representation in the field of visual and performing arts. The title of the publication homages the book of the same name by Georges Bataille (The Solar Anus), in which the concept of anality—as a political device able to challenge patriarchy and heteronormativity—is the sun of a situated understanding and a radical epistemology. The book is a collective body, composed by essays, letters, erotic stories, confessions, poems, and visual archives by the contributors Lorenzo Bernini, Natalia Cabezas, Giulia Crispiani, Caterina De Nicola, Beatrice Favaretto, Giovanna Maina, Jacopo Miliani, Mariacarla Molè, Giorgia Ohanesian Nardin, Linda Porn Davis, Luca Scarlini, The School of the End of Time, Giovanni Testori, TOMBOYS DON’T CRY and Francesco Tola.The backbone of the book consists in a dense essay by Il Colorificio that introduces, contextualizes and expands each contribution featured in the book. The text traces a fictional story intersecting local mythologies with personal anecdotes, political experiences, and contemporary artistic practices: from the disciplinary power of the catholic devotional device of the Sacred Mounts to the performative potential of language; from the practices of self-defence and terrorism in relation to the body and sexuality (stemming from Italian armed struggle to postporn) to the urgent need to regain possession of the public space.

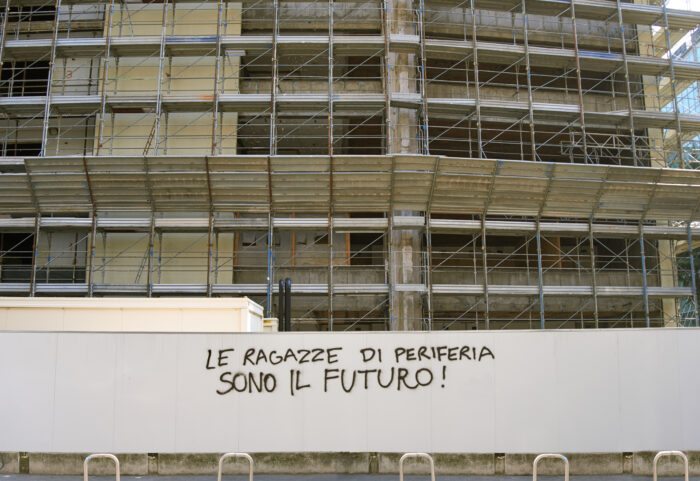

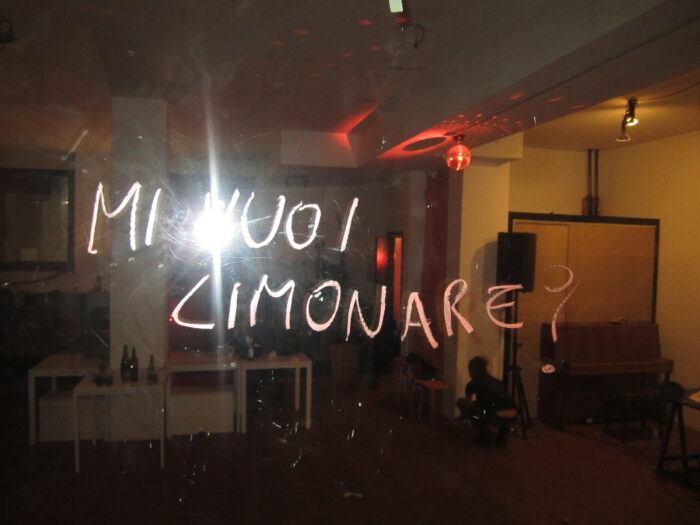

The extract pertains to the second chapter Theaters of Bodies – Performance of the Self and Anal Language. The essay is accompanied by TOMBOY’S DON’T CRY visual archive, which has been featured in the book in the final chapter We are the Sun. The Embrace of the Collective Body.

When the anus is opened, the transparent fictions of identity erected with its suture are contrasted by thick and dark fictions that not only reveal its mechanism, but explicitly use it as a gnoseology. If the subject is unaware, lost in a state of “naive-realistic incomprehension” as to how its self is constructed, not only will those devices have to be illuminated but far-reaching changes also be made to their use.

On a cold November evening, in the back room of a greengrocer’s shop, Caterina De Nicola painted, with words. Sitting on modernist armchairs upholstered in imitation leather, De Nicola faked something that was not there, describing in great detail the paintings (why and how she had made them) that were not hanging on the walls. De Nicola’s artistic practice dismantles the architectural space of the confessional to reveal forever different, thick and interchangeable masks. Her (often erotic and pornographic) texts use diaristic writing as a material (“daily weapon”) and constantly stumble into tangible and modifiable fiction which is always soaked in urine and liquids. The subject that runs through it is a hybrid, dispossessed, embarrassed and embarrassing space that makes the listener uncomfortable, because it is awkward and constantly inadequate for the non-functional role it is called to play.

Through language we can be opaque, dense, interchangeable. Writing is a form of self-projection and, subtracted from the control of the norm, it can go crazy. De Nicola picks up a thread that passes through Mieli and can be traced right to William Burroughs. She shares the same technique as Burroughs. For the American writer, language is a transparent controlling mechanism used by hegemonic power (it names what can be thought and makes it exist, it guides thoughts). The counter-attack is the cut-up: a mode of writing in which different orders and kinds of texts are cut up and then shuffled around to obtain a new one. Language often becomes a material to be blended together and altered. The world is assailed because imaginatively overlapping different parts leads to unexpected juxtapositions. The linearity of production collapses and texts from different eras are piled up in the temporal space of a single page. The cut-up technique breaks the effectiveness of language.

With eyes half-closed amidst the stench of urine, we catch sight of Mieli. Their writing does not follow the cut-up technique, yet it seems that their life results from precisely that. One and infinite, and at the same time Jesus, activist, Queen of Egypt, Jacqueline Kennedy, philosopher, Aphrodite, traveler, Marella Agnelli, reconstructor of mythical royal genealogies and bored museum visitor. “It doesn’t even cross their minds that the dignified lady sitting in front of this work, wrapped in her 1960s chequered overcoat and taking notes, is, as they say, a man, that is, a transvestite: that is, me. I am one of the versions of myself.” Mieli’s schizoid euphoria and performative and imaginative writing blend text, life and performance into a drame that does not distinguish between the streets of Milan, the sex cruising byways, the dark rooms of discos, the F.U.O.R.I! (OUT!) public assemblies or the theater stage. More than anyone else, Maria/o Mieli assumed a transitory and transiting posture, capable of highlighting the supposed antithesis between the sexes and recognising the perennial spectacle in which everyone is called upon to take part.

Mieli constantly piles up the fictional levels and sees verbal or physical performativity not so much as a space of play in which to construct the truth, but rather a stage on which the only possible truth is given: a constant intersection between myths and fantasies. Indebted to Deleuze and Guattari’s reinterpretation of schizophrenia as a machine always producing conjunctions (one is not father, mother, son or daughter but everything at the same time), Mieli also sees schizophrenia as the bastion that recognises the other person’s folly—only miserable clowns, puppets of the system, wooden statues of the sacred mounts. A schizophrenic, on the contrary, rejects that spectacle. A schizophrenic destroys the singular norm and is never alone, because when the self is finally undone there is no loneliness. “If I was Madame Bovary, I deduced, I was Mary, the bride of God. I was also Christ and I had founded my Church on Peter

Il risveglio dei Faraoni (The Awakening of the Pharaohs), released posthumously against the wishes of the guardians of Mieli’s legacy, is more than just a novel, it is a legenda maior, an excited confession, an autobiographical hagiography in which Mieli builds his own myth: that of a body that is not Maria/o but—crowded with presences and schizophrenic—is ubiquitous, is “everybody, everything, everywhere”. In a whirlwind of images whose boundaries waver between dreams and lived or imagined episodes, Mary is the redeemer of the world because, “one and triune”, he sums all bodies and historical epochs in herself, causing the linearity of time to explode: “I, Hitler, was following the orders of the mecreated who have always ruled the universe with raw power and fore- sight.” One is also the other, it is changeant. It is in the changeancy—of the cut-up (De Nicola and Burroughs), theater or overlapping of imaginary formations (Mieli)—that the key to the mechanisms of counter-hegemonic fiction lie: in building a dis-identifying move, which can imagine a body whose “plugging in of organs takes place subject to no rule or law”, perpetually in transit. It is no coincidence that Mieli’s images of life are accompanied by their conviction of an original transsexuality of the body and desire. Starting from the “diverse/perverse” reinterpretation of Freud (and Marx) given by Parinetto—their interlocutor at the State University of Milan—Mieli argues that deep down we are all transsexuals, which is to say that our sexual drive is perverse, undifferentiated, hermaphrodite and polymorphous (exactly what according to Von Salomé happens before the suture of the anus). We were all once transsexual children and social fiction (educastration) has forced us to identify with a precise role, a precise sexual preference, building our bodies accordingly. For Mieli, opening the anus would ensure that we made contact with that original dimension.

In this case, however, we are less interested in possible essentialist positions, and more attentive to the transformative, productive and imaginative significance of transsexuality, as Mieli intends it. This breaks down the material physicality of the body and shapes it (along with language): the open anus opposes the fictions of the hetero-patriarchal system with the self-design (transsexuality) of the body—another fiction. Thus, De Nicola’s pornographic stories and the Egyptian hagiography of Mieli’s Il Risveglio dei Faraoni meet the anarchic, hormone-fuelled experience that Preciado recounts in Testo Junkie: in any case, they are epics of the “reappropriation of the very techniques of the production of subjectivity”—literary and pornographic first of all, imaginative and masked later, and last biotechnical and somato-political.