The Work of Art Is a Fact Itself

Henry Martin’s correspondences

The following article stems from a conversation between the author and Emanuele Guidi, curator of the exhibition Correspondences: About Henry Martin, held at ar/ge kunst from November 2022 to February 2023. The point of departure is in fact the exhibition, both as a form of statement and as a lucid portrait of the figure it concerns.

Within the contemporary system of cultural production, it is a recurrent statement that an exhibition acts in a form of active contrast to the concept of retrospective. Thus, what is retrospective?

Instead of certitude, the exhibition expresses connective possibilities. The question of evolutionary displays. An ongoing life of exhibitions. Exhibitions as complex, dynamic learning systems with feedback loops, basically to renounce the unclosed, paralyzing homogeneity of exhibition master plans. To question the obsolete idea of the curator as a master planner. As you begin the process of integration, the exhibition is only emerging. Exhibitions under permanent construction, the emergence of an exhibition within the exhibition.

Hans Ulrich Obrist, Curating now panel discussion, October 14, 2000

The exhibition that Guidi dedicates to the figure of Henry Martin, a critic and curator who is not well known, neither locally nor internationally, is the beginning of a story of which the designer Martino Gamper participates in the construction of the narrative. Through the use of recycled natural and industrial materials, what is original is kept intact, and what is new and separate from it is assembled around it.

The attempt at this initial research and exhibition project is the identification of a proto-curatorial attitude within the profile of this figure.

But what does the term proto-curatorial mean? Or rather, what does the prefix suggest?

By offering the reader a brief description of his life, I hope it is possible to grasp the meaning of the definition to which we will return at the end of the text.

Henry Martin

(Philadelphia, 1942 – Aica di Fiè, 2022)

“Henry Martin is an art critic and curator who has been writing about Fluxus for almost three decades. He is the author of George Brecht’s The Book of the Tumbler on Fire, and he has published essays on Fluxus artists from Brecht and Knowles to Friedman and Filliou. Martin lives near Bolzano, Italy, where he recently organized a major exhibition for the 30th anniversary of Fluxus.”

This is the biography we encounter at the end of a conversation between Francesco Conz and Henry Martin which took place in 1991. This dialogue already outlines a very precise pool of friendships and working collaborations. Conz, in fact, was one of the main editors of multiples, that he made with Fluxus and the artists of Viennese Actionism, as well as international circles related to Concrete Poetry, particularly from Spain. With Martin, Conz shared the concept of an everyday space designed to be a refuge. In fact, the latter, in addition to his two bases in Asolo and Verona, had a house-museum in the hamlet of Cappella Fasani (Verona), a small village in the Valpantena valley.

For his part, in the early 1970s Martin decided to move to Aica di Fiè, near Bolzano in South Tyrol. The retreat on the heights, in a small mountain village, was a place of respite and peace from where he could continue his collaborations in various cities in Italy and elsewhere.

Prior to his arrival in Italy in 1965 as a lecturer at the Bocconi University in Milan, Martin was already an active companion of the Fluxus movement and its members, whom he had met in New York in the company of Ray Johnson, after studying at Bowdoin College in Maine, under William S. Wilson, himself a Johnson’s scholar. The exhibition mentioned in the biography, entitled Fluxers, was curated by Martin in 1992 at the Museion, Bolzano.

“In the mid-1950s, while yet thirteen years old, Henry Martin haunted the Philadelphia Museum of Art, paying special attention to the Walter C. Arensberg Collection, and in particular, the art of Marcel Duchamp. Fifteen years later, he was in Milan, Italy, assisting Arturo Schwartz in the preparation of the monumental monograph, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp (Abrams, 1969).”

I met Henry Martin in Milan in 1967, and we became friends. Then I left for the US, and Arturo Schwarz asked him to translate one of my texts on Arakawa for Art International, which he did magnificently. But since I left Milan in ’67, I never met him again. The Collezione Maramotti at my request had him translate some of my texts, but we were no longer in contact as we were in ’67. At that time in Milan Martin was a friend of many artists, critics and gallery owners, we all held him in high regard. He was not just a translator, but a real writer, he had a sensitivity for contemporary art equal to that of any critic.

Mario Diacono, from an email exchange with the author

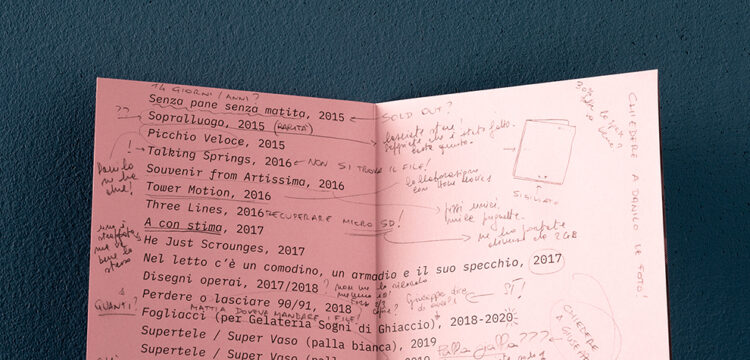

Although after 1971 his permanent base was in South Tyrol, in the company of his wife, the artist Berty Skuber, there was no shortage of sudden moves on the geographical map. Venice, Rome, and New York were among the many destinations for building a constellation of personal and professional relationships based on a strong predisposition to listen. In this, his career bore very significant fruit: co-author of artist’s books, author and curator of important monographs, translator of texts and publications, as well as exhibition curator, performer and producer, Martin has had very diverse roles in the field.

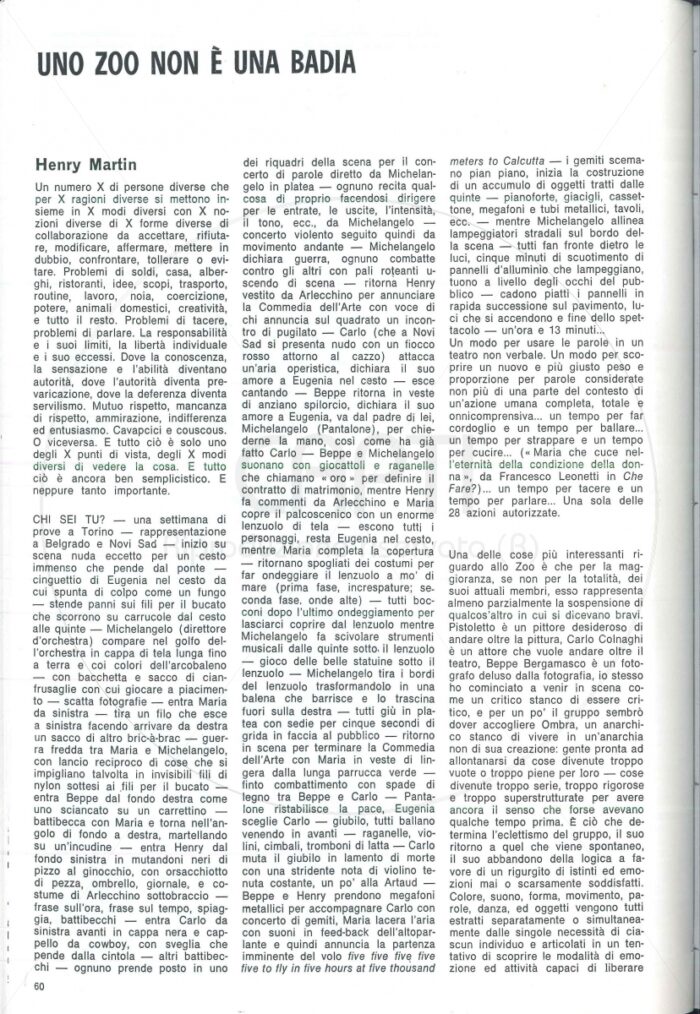

In 1968 he was a performer in Michelangelo Pistoletto’s first Zoo show, L’uomo ammaestrato (The Trained Man). About the Zoo itself, Martin wrote in 1971 in the first issue of Data magazine, in an article entitled Uno Zoo non è una badia (A Zoo is Not an Abbey). In the text, he adopts a layered point of view that allows his dual role as a performer and a critic to emerge.

During these years of cultural ferment, there was no lack of encounters with artists associated to Arte Povera. In 1967, he wrote in the first Alighiero Boetti’s catalog, published by Galleria La Bertesca at Germano Celant’s request, and subsequently edited the first monographs of Arman (1970), and that of George Brecht (1978), entitled An introduction to George Brecht’s “Book of the tumbler on fire.” He is the author of several books on the latter, including A Conversation with George Brecht by Henry Martin, published by Exit Editions the following year. He also curated Ray Johnson’s first exhibition in Milan, at Arturo Schwarz’s gallery.

In Venice, he served on the board of the Emily Harvey Foundation for the support of contemporary artists, poets, and musicians. The Foundation, which owns a collection of over two thousand works acquired by the gallerist from 1983 to 2004, represents figures that coincided with Martin’s circle of friendships and established relationships, including George Brecht, John Cage, Marcel Duchamp, Robert Filliou, Al Hansen, Ray Johnson, Alison Knowles, La Monte Young, Charlotte Moorman, Nam June Paik, Carolee Schneemann, and Daniel Spoerri.

Lea Vergine: So, you arrive in Milan. What year is it, and what impression do you get of the city?

Henry Martin: It was ’65. Everything went through Milan back then; you could see everything there was to see. It was a very exciting city. After ’68, I went to Rome where I did a book with Gianfranco Baruchello, published by Edizioni Di Maggio. Then, not wanting to spend a winter of Roman salons, I agreed to go and live in Aica di Fiè, a mountain village in the province of Bolzano, where a former student of mine had found me a home. I thought it would be good for me to work and ski. I stayed there. Outside the metropolis, I function better, my thoughts have the chance and time to form.

Lea Vergine, “Intervista a Henry Martin,” Vogue Italia, February 1988

The Roman period marked the birth of an important friendship. Baruchello welcomed Martin with extreme generosity, and together they experienced an almost untranslatable dialogue, made up of writings with a double voice.

The story presented here is thus an encounter between an active voice and an active ear—a voice that said everything it found possible to say, and an ear that received it with all possible clarity.

Gianfranco Baruchello and Henry Martin, How to Imagine. A narrative on Art, Agriculture and Creativity, 1984

How to Imagine is an account of the long operation of the company Agricola Cornelia, two years after the end of the eight-year project. It is the result of a series of daily conversations between Baruchello and Martin, held over a period of one month and recorded on audiocassette in the spring of 1980.

The book the two authors later worked on, Why Duchamp, addresses the figure of Marcel Duchamp by questioning the value of his work today, with the intention of discovering the man behind the artist.

The two had met in 1965 in Palermo on the occasion of the V Settimana della Nuova Musica (5th New Music Week), founded by Antonino Titone, during which both the second meeting of the Gruppo 63 and the exhibition project Revort 1 had taken shape.

Proto-curatorial profiles

Lea Vergine: What do you like?

Henry Martin: Doing things intensively that are real experiences. Carrying on an activity like that of an art critic at the most honest level possible. The whole field of poetic and visual creativity interests me enormously.”

Lea Vergine, “Intervista a Henry Martin,” Vogue Italia, February 1988

Trying to reflect on Martin’s curatorial position, the term “honest,” which curiously emerges from the quote above, somehow allows us to perceive his spirit in a sharpened way.

Being a facilitator of relationships is perhaps an aspect of curatorial practice that plays a key role in shaping an active community in contemporary times.

The escape, the choice to live on the periphery, to operate in a dimension of beneficial cultural overlaps that consolidate an extension of the geography of relationships is something that speaks to the contemporary art system.

Whether in the past a term such as outsider could be used to delineate this kind of profile, today the recovery of these practices is matched by the possibility of reinterpreting the concept of the marginal and marginality.

For me this space of radical openness is a margin—a profound edge. Locating oneself there is difficult yet necessary. It is not a ‘safe’ place. One is always at risk. One needs a community of resistance.

bell hooks, Yearnings: Race, Gender and Cultural Politics, 1989

The act of looking, writing, and listening of the African American-born critic and curator has been at the heart of his work in which he has done as much as possible to be with artists—both those he knew and those he translated or wrote about.

It is in incorporating a practice, in feeling it strongly, to the last ounce of oneself, that it is possible to offer a sincere presence in this system.

The re-appropriation of this story and the act of its recovery are part of an urgent civic movement based on the attempt to create new models and modes of narration. That is not always simple, but it is extremely important to contribute to disseminating alternatives and brave experiences of transient identities.

Personal experiences––revised and in other ways redrawn––become a lens with which to reread and rewrite the cultural stories into which we are born.

Gloria E. Anzaldúa, now let us shift… the path of conocimiento… inner work, public acts, 1981

And with this final quote I propose to reconsider the role of a curatorial approach within an institution, today. The circulation of those voices that have not been heard is part of a process of translation and reconfiguration which is plural and works in a space made of relationships in permanent construction. In the layered reality of today, it is increasingly important to institute “otherwise,” as Emanuele Guidi did with this exhibition, admitting our wrongs, willing to interact with what we did and what we are going to do together.