The Voice Shapes the Space

Hanne Lippard’s performative practice investigates the interaction between text, voice and space

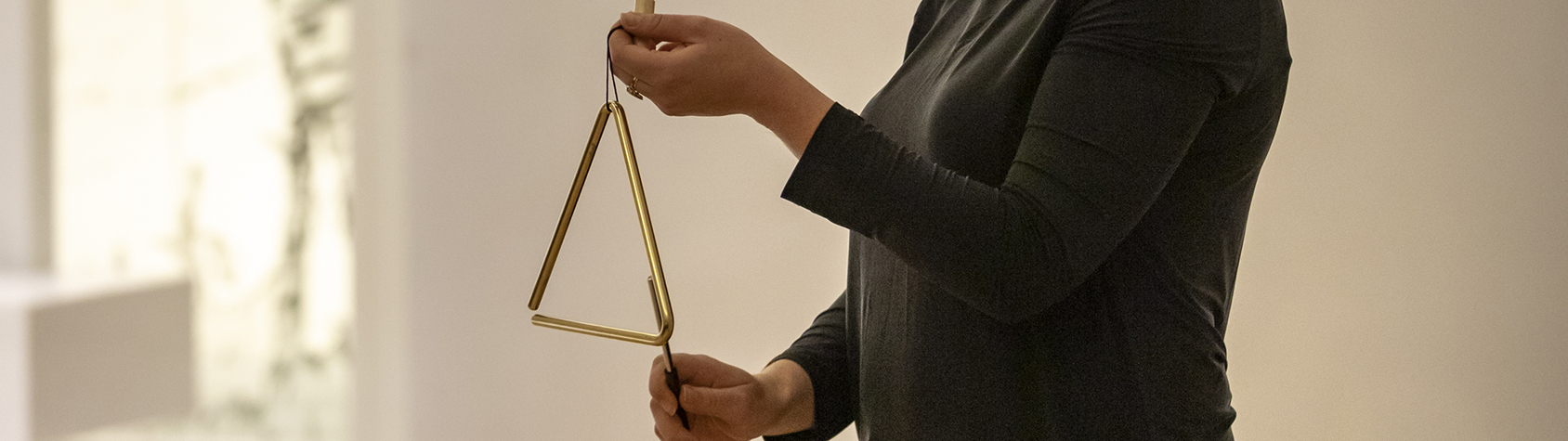

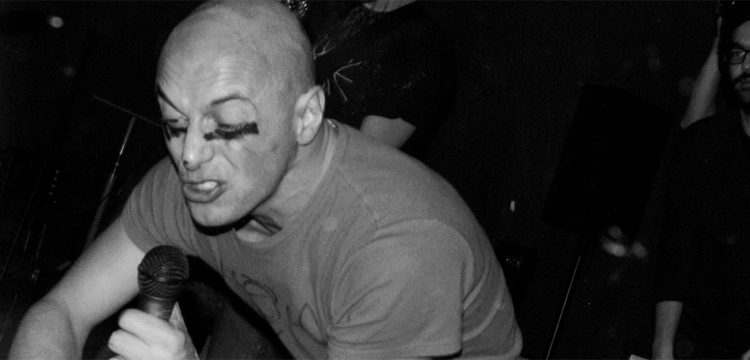

Committing to humanity means to construct it on the basis of language, following our own rules rather than general causes or laws. There is no mysticism nor supernatural component in this enablement by self-imposed constraints, but only words pronounced, declared against their own vocal ornamentation. On Sunday 16 December 2018 in Bergamo, the Church of San Giovanni XXIII has become an exceptional element within Hanne Lippard’s practice. Syzygy is a performance through which the artist sculpts the space with the sole aid of her own voice and her own presence on stage. The church, the artist and the spoken word make up that special configuration the title of the work is referring to, namely the syzygy: an astral alignment, understood as a harmonious order necessary for something to be created.

Photo Roberto Marossi

Ginevra Bria: How could your single voice represent all the multifaceted epics of your performative and narrative research?

Hanne Lippard: I believe my method aims to transcend and make sense of the cacophony of information one is constantly subject to, both offline and online, both for myself and hopefully for others.

The expression l’exigence de l’oeuvre entails the peculiarly harsh demand that the work cast upon the creator, which is different from the demands of any other task: that all his powers would be plunged into weakness, that it comes into an immense wealth of silence and inertia. What is the meaning of silence in your performances?

Silence is one of my favorite tools in performance; fragile yet very effective, it needs nothing other than itself in its non-existence. To use it well is an art in itself, and it is something I have learned over time to implement my readings with.

As Blanchot stated: To write is to make oneself the echo of what cannot cease speaking—and since it cannot, in order to become its echo, I have, in a way, to silence it. What is the visceral bond, the connection between voice and writing?

It is interesting to work with both speech and writing combined, because I deal with embodiment on another level. To convey the texts as time-based pieces, existing in that very moment rather in the pages of a book or hovering online on an eye-tiring screen, is more interesting to me. There is a sense of urgency in this kind of practice.

Photo Roberto Marossi

You’re fond of literature but you also studied graphic design at the Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam. Did you also studied or approached visual poetry at all?

No, poetry has only come to me in later years. I did partake in a short novel writing course when I was twenty, where I quickly realized I am unable to write novels, at least in the rigid way as novels are perceived in Sweden.

Which writer could you consider as your personal meister and which artist? Why?

I admire the work of the poet Anne Carson, she writes poetry in a way that is very approachable, and at the same time very profound. She manages to move between different moments in time; from ancient Greece to contemporary aspects of North America. Also the writings and works by Samuel Beckett, as well as Gertrude Stein inspired me early on.

While witnessing your performance the spectator becomes both a viewer and a listener, is it possible to consider your voice as a mean of a visual rituality, an instrument enhancing also a maieutic duality in the public? How did you discover the potentiality of your inner voice?

I was interested in theatre before I started studying, so I had some insights in the concept of acting out a character. Later, I ended up studying Graphic design, within an academy that has an open interpretation of graphic design as a tool for conveying language both rhythmically and visually in many ways other than pure typography. There I have started to develop a text-based practice that focuses on the use of my own voice.

Photo Roberto Marossi

Performing the piece in the hospital church provides an equally enigmatic ambience, just in a different setting, with the presence of religion rather than historical ideology. You recently stated that Syzygy is a natural phenomenon, a constellation of planetary conjunctions, specifically of the moon with the sun. How do you allow to visualize and listen to a brand new plasticity between poetry and performance in Bergamo?

It’s not so much the performance itself that imitates the natural phenomenon, but rather the text. The reading tries to connect events and phenomena, both human and natural, that may—or may not, as some of it is pure poetry or fiction—have happened in different moments in time. The first version of this performance took place during the 6th Moscow biennale in 2015, in the VDNHK central pavilion, a large exhibition space from the soviet times with a dome like structure, the strong presence of the Soviet ghosts lingering in the room.

Your work was recently on view also at Kunsthalle Wien, within Antarctica. An Exhibition on Alienation’s parcours. How is your work related to the concept of social coldness and rigidification?

Both the topics and the execution of my work lie somewhere between the human and the mechanical without being hyper-digitalized, locating the human veins between the digital wiring of language. The specific piece shown in Antarctica is titled Anonymities; a six channel installation of a repeated attempt at pronouncing the word “anonymity” a word I often struggle to pronounce correctly because of the m’s and the n’s.

Photo Roberto Marossi

Is there a verse of a poem, you often repeat to yourself in order to concentrate on yourself before the performance occurs?

As I am rather autodidact, I have surprisingly few rituals I usually do before a performance. But I do try to go through a few short exercises, the repetition of the letters -s -p and k- to warm up the voice, something I learned when I was in a drama group as a teenager. Moreover, I need the day to be rather silent and meditative, so I prefer to not travel or stress the day of the performance. I also prefer to be alone the hour in advance, or at least not to communicate too much. The following day I am usually very tired even if I only read for less than 20 min, like the oracle in Delphi who would pass out after her recitals.

Between the publications Nuances of No and This Embodiment, how has the structure of your post-script work been evolving?

Both books have functioned as text binders I used in my practice in previous years, before the book was published. Once the book is there in front of me, I suddenly see a distinct pattern in the topics I have been working on, both in performance and installation, a very satisfying clarification of what might otherwise seem incoherent to each other when you are in the middle of the process.

Photo Roberto Marossi

Have you ever noticed how your way of writing evolved through time, in preparation to a performance?

Since I started using my voice to utter text, the voice became an intrinsic part of the act of writing. During the act of writing, at times I write and speak simultaneously in my studio. The regularity of public performances and readings also helps me to write better texts. It is often when I first feel the text in my mouth and hear it resonate in a room, that I realize whether it works well or if it could be better developed for the voice.

The texts might seem autobiographical and confessional at times, but they are in fact often narratives belonging to others, in existing or invented bodies. When does a body, of flesh and bones, become a whole with the voice? Which is the knot tying them?

I would answer this with a quote from the aforementioned writer and poet Anne Carson: “every sound we make is a bit of an autobiography, a piece of inside projected to the outside” (Anne Carson, The Gender of Sound).