The Un-body

Guerrilla against the unceasing hostilities of the living—Part #2

The Institute of Things to Come is an art programme aimed at investigating forms of imaginative speculation as cultural strategies and methodologies for critical positions, founded in 2017 by curator Valerio Del Baglivo. Its current 2020-2021 program, entitled “The convention of restorative anatomy and prosopopeia” questions the categories of alterity in opposition to current politics of sovereignty, national belonging, and heteronormative approaches in Europe and beyond.

Along these lines of research, The Institute started a collaboration with NERO and invited curator Michele Bertolino to publish a series of texts all along 2020-2021. Derived from conversations with experts in zombie studies, queer theory, post-porn productions and anticapitalist imaginaries, these essays discuss the figure of the zombie as a critical entity, a material paradox and an oxymorical body, aiming at developing pragmatical tools for a collective body.

Our guerrilla is reorganizing. More than one year after its beginning, the persistent COVID-19 pandemic has transformed our lives. If ten months ago we were witnessing growing signs of an imminent change, as newborn mass movements and revolutions were declaring the urgencies of our collective body, now we have landed in a quiet land of resignation. Distances have increased. Eyes crookedly stare at each other.

The witnessed collective body left the stage to an unprecedented wax war. Bifo Berardi recently pointed out that the shift happened during our viral age: we no longer fight as one being against the counterattack of nature, rather we are lining up, competing with each other for vaccine availability. Immunity substitutes collectiveness, since the former is being acquired without any regard for the latter—as the striking inequality of vaccines’ supplies confirms. Indeed, if we recall what some GOP members barfed out last year, and what was further discussed in the conversation with Sarah Juliet Lauro, capitalism—as a form of power—is showing its inescapable necropolitical foundation. Still, we can overturn the table. As Mbembe widely argued, “under conditions of necropower, the lines between resistance and suicide, sacrifice and redemption, martyrdom and freedom are blurred”. Death resolves in an over productive act in and for itself because from and over death the being has power, death is where freedom and negation operate. It is the very principle of excess—an anti-economy.

Here they come again. Zombies serve once more as equivalents, metaphors or, to be more honest, as compasses through which we can reshape the meaning of collectiveness. The Un-subject—the first conversation of this project carried out with Sarah Juliet Lauro—explored the deletion of the subject, being it a part of the subject/object divide which has been blown up by the paradoxical nature of the zombie body and its unresolved negativity. The un-subject has an intermeshed body that hosts no subjectivity but asserts its transcorporeality. Yet, I believe the next step leads to the re-discussion of society. What’s left if we are merely bodies?

A world to dismantle

I have been dreaming of taking this next step, as I speculated with Lee Edelman. As a prominent queer theorist, Edelman published No Future (2004) and Sex, or the Unbearable (2014)—among other books—fostering a so-called antisocial approach to queer theories, where negativity and the death drive are placed in a central position. Opposing to Butler or the last Foucauldian liberitarian philosophies, Edelman’s queer theory no longer strikes society to fight back in order to accomodate those who have been left out, rather it disintegrates society itself. The queer subjects become the triggers for the disappearance of society. Yet, our conversation could not take place. We extensively went over these issues on several irregular calls, emails or random exchanges, but I must navigate them alone, directed by Edelman’s guidance and words.

How can corpses, limping around with a barely attached arm and an exposed skull, be compared to queer bodies? With respect to Edelman’s thoughts, both zombies and queers share a similar dismantling force. Intermeshed with tissues that are both dead and alive, they erase the subject, being both the bearers of the death drive that lies as an integral—yet terrifying—element of our reality. They oppose the order of meaning and the logical structure of the world by negating it. They already represent a different time and space.

With this in mind, I shall reconstruct Edelman’s psychoanalytical Lacanian framework, within which my statements could be understood. In the second book of his seminar, The Ego in Freud’s Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis, Jacques Lacan identifies each and everyone of us as speaking subjects. Our birth is established by a constitutive lack. We are granted access to its order of meaning and become aware of it either through language, logic or through the law. They provide us, as speaking subjects, with “an immense message into which the entire Real is little by little re-transplanted, re-created, re-made”, creating our reality or, as Lacan calls it, the Symbolic. Yet, the Symbolic exists in perpetual incompleteness—a single word could never wholly grab the object whose it is referring to. Ultimately the Symbolic prevents subjects from embracing the Real—“something in front of which words stop”—foreclosing its complete grasp. Desire is born out of and is sustained by this lack. Desire, while aiming at the erasure of the ontological distance which separates us from the Real, fuels the continuous verbal, logical and meaningful production of our imaginary and of the Symbolic order. Still, such an overflowing production cannot but widen the pit which prevents us from the instantaneous enjoyment of the Real itself. The speaking subject then merely becomes the subject of an unattainable desire.

It is against these considerations that Edelman elaborates his reading of contemporary society. Desire unfolds the future as that space in which the Imaginary tries to fulfill the Symbolic. Yet, the Symbolic cannot be fulfilled and the future merely serves as a placeholder that assures stability while perpetuating Symbolic incompleteness. Thus, time identifies as a narrative engine for our dreams of self-realization, fueling the promise of being and meaning in one, which ultimately could only be realized in the Real. Politics is its methodology. Conforming to the temporality of desire, it translates into a narrative, teleologically determined by its scope: the reproduction of the Child. Edelman locates the Child as the telos of social order—the prop for our secular theology. “It comes to be seen as the one from whom that order is held in perpetual trust”. It structures our logic of futurism, which meaning always depends on, shaping our collective narratives. In conclusion, the Child assures the Symbolic order by ontologically sustaining time by impersonating the future. Desire, on the other hand, maintains our social order by refusing “its satisfaction or enjoyment, prolonging itself by negating the satisfaction at which it aims”—Edelman concludes.

Edelman elucidates such a conundrum with reference to the so called “pro-life” activism, homophobic politics, nationalistic, familistic and sexist discourses, as well as movies and books. Yet, I would refer to Helen Hester’s Xenofeminism, where we can find neat examples of such an understanding. Climate change activism often operates using the Child as a “handy rhetorical shorthand for the future itself”, thereby inadvertently promoting the values of reproductive futurism. Children have pivotal roles in marketing campaigns—posters’ promoting the 2014 “People’s Climate March” in London, New York and Paris, portrayed an ethereal child clutching a toy windmill while staring wide-eyed into the future—and appeals on behalf of them could not be refused: “What future will our children have in such a polluted world?” Out of a strict Lacanian framework, Edelman’s unsatisfied desire unfolds poignantly: desires are produced, exchanged and consumed but never fulfilled—as GMSNAs [gay male social network applications] widely accounts for—yet they feed a Symbolic order where both our commodified-language and driven-choices serve capitalistic algorithms used to design the future and our earnings—as Avanessian and Malik or Elena Esposito argued.

The theoretical conundrum

Hitherto, I mentioned a dismantling force, shared by zombies and queers: they exist as bearers of the death drive, while possessing an unrestrained hunger. Using Lacanian words, which will eventually be clear, they jeopardize our Imaginary conundrum by dismantling our Symbolic order. At this level, I believe an example could give us some clarifications. Most zombie movies have the same structure: healthy men and women—wrenched by sonic radiations, experimental chemical products or unknown viruses—turn into zombies, becoming the enemy to run from, the bodies we cannot touch, kiss or have sex with. Take World War Z as an archetypal case, where the zombie horde ferociously rushes around, consumed by a single impulse: they starve for meat to bite. Whole beings shrunk to a single impulse viciously dissipate into the immediate satisfaction of their craving, rather than prolong an unfulfilled desire. Their mob goes through that impulse which results in the principle that acknowledges the very possibility of their existence and constitutes their society of bodies. Ultimately, they oppose the speaking subjects, destroying the reality erected via the Symbolic order.

Edelman provides some clarifications. As soon as the speaking subject arises, a dark twin originates: the subject of the drive. “It functions not in a mode of absence [or lack, as the subject of desire does]—Edelman argues—but in a mode of an impossible excess haunting reality”. It is driven by a free jouissance, rehabilitating an immediate connection with the Real, while paying the price of the sudden suppression of the subject as we know it. Indeed, it exists outside the logic of meaning, as surplus. Jouissance, which directs it, is “a movement beyond the pleasure principle—Edelman states—beyond the distinctions of pleasure and pain, a violent passage beyond the bounds of identity, meaning and law”. Language is destroyed, meaning disappears, while the body is fully absorbed in the senseless drive of that indulgence, which implicates sexuality as its engine. As a matter of fact, jouissance evokes the death drive: an impulse towards the end directed by the refusal of any identity or the absolute privilege of any goal. It signifies the negativity—recalling what Sarah Juliet Lauro addressed as negative dialectic.

To solve this theoretical riddle, it might be necessary to take a brief step back. Shortly, in Civilization and Its Discontents (1929) Freud locates two opposing, yet interlocking, forces—eros and the death drive—whose mutual action develops society as a form for communal living. Eros preserves unity, tethering together the organic as well as the subject, by opposing the death drive whose only aim is dissolution. Sexuality, if not limited to the heterosexual intercourse—thereby directed toward the reproductive futurism of the Child as Edelman would say—carries the burden of such an undoing. Following Freud’s reflections, as elaborated by Lapanche and Bersani, sexuality is “an aptitude for the defeat of power by pleasure, of the human subject’s potential for a jouissance in which the subject is momentarily undone”. As a matter of fact, sexuality carries, through its association to the death drive, the negative value of unproductiveness, abjection and ultimately asociality.

Out of the metaphor, zombies are those dark twins—their insatiable hunger means nothing but that unrestrained jouissance. Once more, queers and zombies embody that jouissance, guided as they are by the death drive. Dwelling into a Lacanian Real—in front of which words stop—they destroy politics, as the methodology for the social construction of reality, and negate the self, as a mere prosthesis maintaining the future for the figural Child.

Ultimately, they both are sinthomosexuals. Edelman coins the term making explicit reference to homosexuality “understood as a cultural figure, as the hypostatization of various fantasies that trench on the antisocial force”. Homosexuality (or, more broadly, queerness) is often seen as a culture of death—namely a culture whose sensory experience and pleasure of the flesh borne away from a fantasy of secured futurity. Sinthomosexual refuse “the Symbolic logic that determines the exchange of signifiers”, their “sinthome—Edelman adds—procures the determining relation to enjoyment by which the subject finds itself driven beyond the logic of fantasy or desire” to the shores of unrestrained jouissance and lustful carnality.

Thus, queers and zombies undergo the same description, both unwittingly accomplishing the same task. Not only do they threaten logic (as Sarah Juliet Lauro accounted for), but they embody the death drive. “The concept ‘dead’ functions as coinciding with its negation—Edelman says—the death drive designates the dimension of what horror fiction calls the undead”, namely the zombies as those strange, indestructible beings persisting beyond the death of the conundrum of our imaginary reality.

Un-subjects as bodies of the drive

Sinthomosexuals are subjects in their own way. “Sinthomosexuality links the jouissance to which we gain access through the sinthome with a homosexuality made to figure the lack in Symbolic meaning-production”—Edelman explains. Thus, jouissance identifies with the unavoidable engine of the subject, being now the subject of the drive. Sinthomosexuals are thus still singled out in their own distinctive shapes. Forcing Edelman’s words, I would say that since the release of their subjectivity, previously suppressed by the loss of meaning, they are mere bodies defined only by their insatiable hunger. They are bodies of pure drive.

A little detour will allow me to link these preliminary conclusions to Lauro’s considerations. Stemming from Freud’s psychological riddles, the death drive has widely informed antisocial queer theory—as Edelman, among its prominent members, proves. Leo Bersani, philosopher and professor at Berkeley University, advocates for the death drive being the constitutive element of any effective queer theory. Published in 1987, Is the Rectum a Grave? confronts the AIDS crisis, which impacted the TLGBQUIXYZ communities, wiping out their members, ideas and energies. Bersani takes a challenging stand, affirmatively answering the question the title asks. When the whole prig society was identifying the rectum as a grave for thousands of bodies (see Simon Watney Policing Desire: Pornography, AIDS, and the Media, 1987), Bersani was corroborating it. The AIDS crisis manifested the potentiality of death which patriarchal society was already associating with homosexuality and Bersani agreed, yet turning it upside down. “If the rectum is the grave in which the masculine ideal of proud subjectivity is buried, then it should be celebrated for its very potential for death.” The rectum values powerlessness, not in the mood of gentleness or passivity, “but rather of a more radical disintegration and humiliation of the self.” Ultimately, the rectum carries the death drive: it dissolves the self, shooting it. In other words, it embodies the jouissance “as the ecstatic suffering into which the human organism momentarily plunges when it is ‘pressed’ beyond a certain threshold of endurance.”

Edelman and Bersani reinforce Lauro’s conclusion on the dissolution of subjectivity, while they introduce jouissance and the death drive as characteristic features pertaining to these bodies. They stress the pars destruens of such drive, yet they value unproductiveness, abjection and asociality—as well as death—as potential pillars onto which a new corporeality is shaped. Still, I need to answer the opening question of the articles—what’s left if we are merely bodies?—and I guess it is about time.

Tricks and threats

That zombies, as queers, pose a threat to our world is widely certified by the vigorous military reactions in most zombie movies. Yet, what do they consume? Following the theoretical path which has led me here, I could draw some conclusions—bearing in mind that death could be read as an over-productive act (with reference to Mbembe). Zombies erase society and wreck time.

The dialectic of desire is defined through the endless unfolding of futurity and its ontology evolves as a linear narrative where a perceived fantasy of realization pushes towards what happens next. The neoliberal political vision adapts a vision of prosperity to a promise, which could only be fulfilled in the future. As an example of such rhetoric, the Next Gen EU advocates for a “greener, more digital, more resilient” future, promoting its measures through the image of a smiling child—as Edelman has rightfully anticipated. Indeed, such a future is always postponed, merely serving as a placeholder for stability, toward a perpetuating sameness—an œdipal time which unravels as a linear promise, holding the Symbolic order in perpetual trust.

Yet the sinthomosexual’s death drive sprouts as an enjoyment that is always at hand. The sinthome, through which we gain access to jouissance, never ceases to write itself—as Edelman states following Lacan. In other words, the sinthomosexual gets lost in a repetitive compulsion that disengages from the narratological idea of time. The zombie’s insatiable hunger, its perpetual craving for brains to eat, could not classify as a perpetual present, and neither does it unravel as circular time. Rather it is just what it is: a jouissance that takes over meaning and logic in the queer and now. Basically, the zombie (as body of the drive) kills the subject not only erasing its meaning and logic order but nullifying the temporality that construes its secular theology.

Thus, zombies are the gravediggers of our social order, invalidating politics which function as social glue. As a matter of fact, the political discourse conforms to the temporality of desire, it needs a fantasy of the future in the figure of the Child, fostering the logic of futurism as a collective reproduction. Following Edelman, politics fuels mutual recognition, upholding the reality in which we live. Yet, when desire vanishes in front of unrestrained jouissances, politics misses its engine. Zombies wreck time and erase politics, allowing for nothing but wandering bodies.

Imagining a zombies horde

To conclude, zombies weaken society and freeze time. They exist in their jouissance, collapsing onto the mere carnality of the contagion which glues their mob. They assemble through their contamination and impulse, they tie through their liquid intimacy. Rather than subjects of the drive, then, they are bodies of the drive. Yet, since they are merely bodies, they convene in a mob, a horde and they rarely attack alone. Once more, what’s left if we are merely bodies? Nothing but bodies, which eventually can join in.

Edelman will help me clarify this last passage. In his examination of Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963), the author identifies the flock of birds, which attacks Bodega Bay, with the death drive. “They were after the children. To kill them” Melanie states reacting to the infamous birthday party at the beginning of the movie. Edelman links the flock to the sinthomosexuals, as they both threaten reproductive futurism. The birds, as a flock, and the zombies, as a mob, come to figure “the arbitrary, future-negating force of a brutal and mindless drive”. Yet, they act, starve, crave as a group.

The sinthome—which possesses those bodies of the drive, as a figural expression of the death drive—means by no meanings, indeed it is “the violent undoing of meaning, the loss of identity and coherence, the unnatural access to jouissance”. Yet, could the sinthome assemble? Sinthomosexuality has been understood with reference to jouissance, as well as sexuality: could a new collectiveness rise from the ashes of the undone, from the grave left empty by the walking zombies? I believe it can. Zombies—and queers—can redefine death as a pro-active force, re-describing intimacy and openness as pillars for our new collective being. However, I still need to see the porous shapes they are going to trace. The next chapter will discover our new borders, designing a new body, deeply rooted in sexuality.

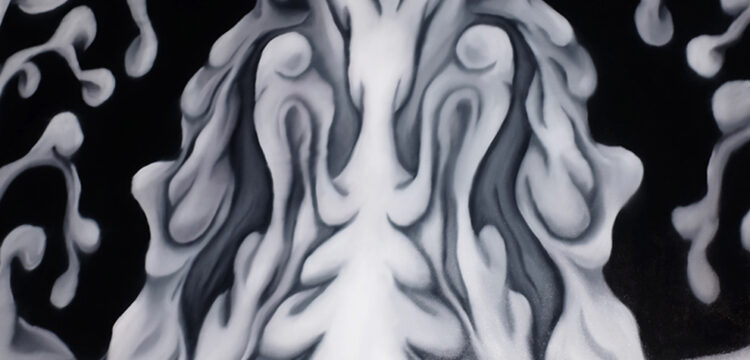

*The visual essay accompanying these words is specifically developed by MRZB, a collective based between Torino and Amsterdam. Their collaborative and nomadic studio-practice relies on an aesthetic and affective research of the peripheral, the marginal and the discarded.