The Transformative Chaos of Love

Marta Federici in conversation with Alice Visentin

This conversation took place in the months of November and December 2022 via emails, phone calls and during some long walks through the streets of Lisbon. Snippets of thoughts, shared with each other during a dilated time, are recomposed in this sequence of questions and answers. The starting point for our exchange was My Heritage, a work of public art by Alice Visentin, which was designed for Piazza San Sebastiano in Limone Piemonte. This area was one of the most affected by storm “Alex” which, in October 2020, brought devastation to the Tanaro, Vermenagna, Gesso valleys in Italy, and in the Roya Valley in France. In our conversation, we delve deeper into some of the themes that nourish Alice Visentin’s research and practice, providing a glimpse onto her recent production. We talk about desiring bodies, earthy soils, hydromantic paintings, dreams, whispered words and gardens.

Marta Federici: My Heritage is a composition of painted ceramic elements, which extends over a 34-meter long wall. The work was inaugurated in the square of San Sebastiano in Limone Piemonte last September and takes inspiration from a local story, featuring six women as protagonists: the skiers Elisabetta Astegiano, Elisabetta Bellone, Margherita and Franca Bottero, Anna and Caterina Tosello. When they began their careers in the 1950s, these sportswomen, still very young, had to measure themselves against a society that was still deeply male and sexist–the second wave of feminist movements had yet to take hold. It’s a complex historical phase, during which Italian women–after having taken part in the Resistance against Nazi-fascism and having acquired the right to vote–were pushed back within the walls of the home, once again destined to domestic work and family care. In parallel to the economic boom, between 1959 and 1965, more than one million women lost their jobs–these figures are impressive. Le Cavallette (the “Grasshoppers,” as the six skiers from Limone Piemonte were nicknamed) could not participate in the 1958 World Championships or in the 1960 Olympics because the FISI (Italian Winter Sports Federation) preferred to invest the available funds to support the male team. Their career experienced the bias of an unjust system, and still, the young women decided to confront it, in order to pursue their dreams. Your project celebrates their courage and their memory, while developing a broad reflection that touches on many themes, such as climate change, the connection between bodies and territories, desire, the construction of narratives. I would like to start our conversation by asking you about your relationship with the local area, and about how it was for you to engage with the community of Limone Piemonte. How did your initial intuitions for this project evolve after the encounter with the place?

Alice Visentin: Whilst I was working on this project, between 2021 and 2022, I often drove to Limone Piemonte, sometimes with friends and sometimes alone. Limone is situated in the south of Piedmont, near the border with France or Liguria. Before catching sight of the village, the ride takes you through long and steep curves. Along the road, firs, rhododendrons and wild azaleas climb up steeply and directly onto a small stream. Each time I went to these mountains, I felt the cult of rivers, trees and ancestors closer to me: when arriving in Limone, everything calmed down. As a starting point for the research, I had planned a series of open participatory moments of sharing for people of different age groups. The workshops were organized together with Ilaria Quaglia, an artist and performer who followed me in this journey, and with whom I had the opportunity to deepen a research on bodies and movement. Even though the restrictions caused by the Covid19 pandemic brought some difficulties, I still tried to talk to as many residents of Limone as possible, and asked them to share stories and memories with me. I wanted to let frictions and twists emerge, in a multivocal narration of the memories of the place. The invitation spread through word of mouth and I began to meet many women in small groups in the library. They came to chat, and tell me about their lives. I remember a school teacher, who left the room without saying anything, simply handing me a handwritten note with a list of words which represented her life: Elsa, teacher for 40 years; botanical garden; mountain pasture; telephone number. Or, another woman, very elderly, who told me of how she started working as a midwife at the age of fifteen: during the first birth she assisted, she wore a pair of baby blue trousers that got indelibly stained. Everyone’s inner worlds, as vivid as they are, are not always easy to render in a narrative. I continued my trips back and forth for months, feeling that every time I left, the pieces of stories of the people I met remained attached to my body. Today, I think back to those intimate moments of sharing as a radical and exciting action. I rediscovered the enormous richness contained in every single conversation, the infinite possibilities that derive from it. Despite this, I struggled for a long time to understand what I was doing. The feeling of making mistakes was a turning point for me: when I found myself alone in my studio, I realised that listening in an apparently passive way to all those micro-stories, those intimate and marginal tales, was already an act of production. By mixing real facts, memories and details, I was able to visualize a collective, complex and plural imaginary.

It strikes me when you say “the pieces of stories of the people I met remained attached to my body.” I recalled some of your works, where the bodies of the characters you draw or paint are filled with fragments of visions and words, such as the silhouettes of the Malefate, which you presented last year in your solo show at Almanac Inn in Turin. I was thinking about how it is not only the stories we live through that change us, but also the ones we receive or listen to, how they have a physical impact on us. They can affect the way we walk, or how we tilt our heads to one side, they can change the awareness we have of our body. Sometimes, they make us heavier or sometimes lighter, they satisfy us, or perhaps they make us feel hungry. Sometimes we can wear a story like wearing a dress–as the women you involved in the performance Sogni I, which took place in August 2022 during the fourth edition of Traffic Festival. The imaginary that gradually took shape through the stories you collected, including that of the Grasshoppers, is a world of memories but also of wishes and desires emanating vortexes of centrifugal energy. From this complex panorama, how did you isolate the elements you wanted to represent, and organise them into shapes and colors? I was looking at some photos of the work. The large glazed ceramic figures seem to float against the grey background of the wall and come alive in a dance.

Working on this project made me understand how it is not only stories that change us, but how geographies do too. Earthly soils, floods, earthquakes, climates and migrations shape us and inscribe themselves onto our skin and also deeper, in our bones. Whilst I was working on My Heritage, I was simultaneously developing several other projects, such as Sogni I. Both of these works deal with a visualization of bodies, moving according to their emotional states. I was working with the choristers on the performance for Sogni I, and at the same time I was organizing the meetings with the women in Limone Piemonte. I walked and traveled a lot in those months, and moving allowed me to immerse myself in different imaginaries, relating to different times and moments, which were merging with one another before settling in my personal archive. The hardest part of the process was undoubtedly choosing and synthesizing. From this perspective, the movement research developed with the help of Ilalia Quaglia was very important. When my eyes met the wall in the square–which had been hit by a flood not long before, in October 2022–I immediately thought of the possibility of developing a long poetic narration, as if it was on a magnetic tape. A magnetic tape is an object which is used to contain memory–in the form of data, video or audio tracks–but it can also be written over or manipulated. I imagined inserting the ceramic bodies inside this “magnetic tape” in order to manipulate those dynamics of social amnesia which often remove the stories that are considered minor, such as that of the six skiers, a group of young women of humble origins, all sisters or cousins to each other. I drew the figures and I modified them over time, defining the general effect I wanted to achieve. I wanted to create a composition which included people, natural elements and moving objects. I wanted the elements to be stylized and realized in ceramics, because it is a material which I often used in my teen years. I used the englobe, a colored clay to be applied on ceramics that has already been bisqued, which levels the surface and makes it waterproof. This technique allowed me a final result rich and varied in color.

As you pointed out, the forms you realized are characterized by brilliant and saturated hues–bright yellows, reds, oranges, intense blues. These colors make the figures even more alive, vital. I recall some words by the poet and painter Etel Adnan from an interview that a friend sent me a few months ago. Talking of colour as a language, Adnan explains how it is through it that nature expresses its intensity: what she describes is a nature that is “alive and conscious” and in constant transformation, which through color manifests “its presence, its power.” But then she also says that in a painting “It’s more than shapes and colors, it’s more than what you see. Your total inner world.” I wanted to ask you to tell me more about the function of color in your work. (in the same interview Adnan also recounts that once someone asked her who the most important person that she ever met in her life was, she declared that it was a mountain: Mount Tamalpais, which she could see every day looking out the window of her house in California. I think that’s a beautiful answer).

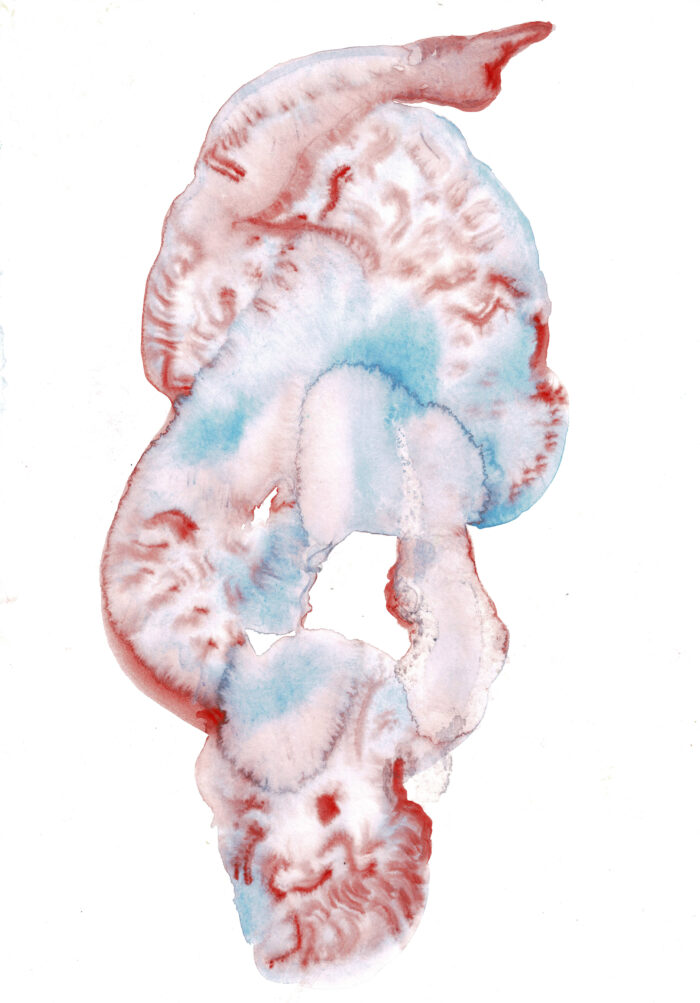

First of all, I would like to underline that the choice to use an organic material like clay, durable and unalterable over time, stems from an ecological reflection. Coming from the ground, clay already contains within itself thousands of stories, and offers the possibility of creating new ones. In this case, I used color to highlight the full and empty spaces in the composition, so as to create a sort of punctuation in the thick web of stories I was handling. The support for the work is a pre-existing wall, a rough reinforced concrete wall, which I decided to leave unchanged, and enhance its qualities. During the set-up phase it was necessary to clean up the surface, but I can’t wait to see it covered again with moss and salt water stains, which characterize mountain roads in winter. The “total inner world” mentioned by Etel Adnan reminds me of a particular way of painting that I am using more and more often, and which I define as “hydromantic.” Hydromancy is an ancient method of divination based on the observation of water. In this technique, which I am experimenting with, I mix water with watercolors or colored inks and let it settle on paper and canvas, allowing it to freely create inlets and geographies of sedimentation. For me, it is a way of treating colour with intention and trust, but without constraint. The bond I have created with water in my latest works has enabled me to follow its unexpected flows. Even the coloring of the ceramic put me in a somewhat analogous condition: I used natural clays, the crystallines, and waited for the firing process to end, in a high temperature kiln, without being able to predict 100% what the result would be.

Going back to one of your earlier points, I’m very interested in what you said about how not only histories but also geographies change us. I’d like you to tell me more about how you experienced the relationship with territories, starting with how the places and landscapes you’ve encountered so far in your life have informed your way of being and looking, and your artistic work.

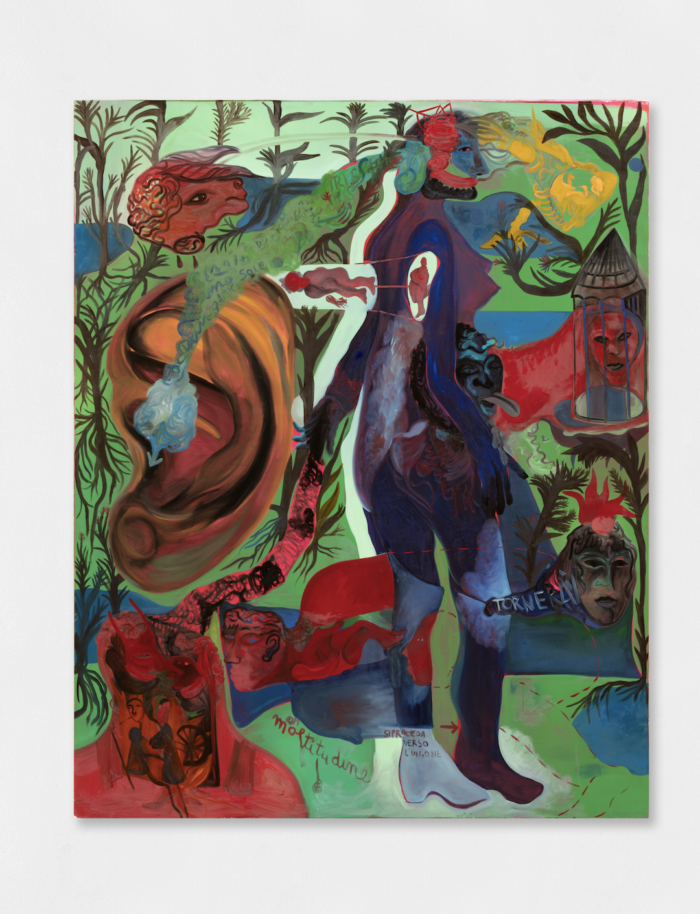

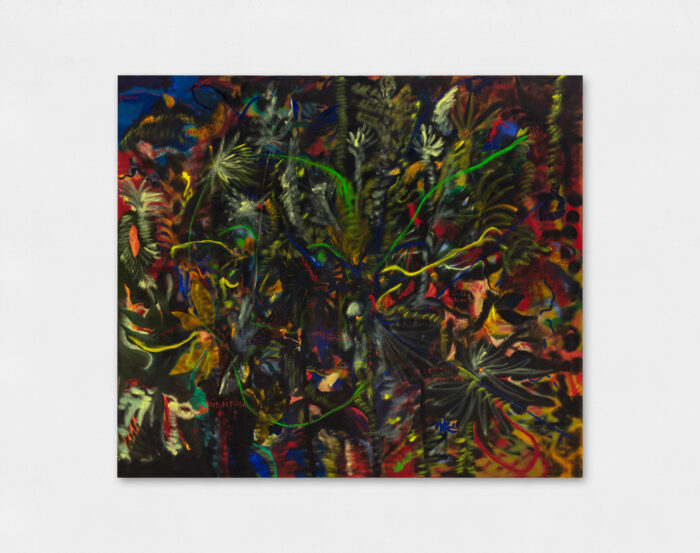

I would say that I started to cultivate the admiration I feel for the planet in the garden of my house, in a small mountain village, where I observed the mysterious connections between vegetation, animals, and the words and movements that my body as a child led me to discover. It was precisely the garden that, years later, allowed me to give life to many of my first pictorial works. Within the canvas, I tried to recreate those secret interconnections and relationships that I had experienced in reality. When I’m in front of a painting I often find myself imagining that I’m going on a sort of initiatory journey, which in many ways is similar to the one I experienced when creating my universes as a child. For example, the painting Fino alle mie orecchie comes to mind, where I represented the path that the outside world follows in order to enter a human body. At the same time, the human body, intertwined with the outside world, transforms itself and accumulates symbols, like an archive, storing them within itself. Growing up, I encountered other geographies, and let myself be contaminated by new and unknown environments, for example when I moved to live in the city. After my school years, I looked for a space in Turin where I could work as much as possible in contact with nature. But my studio was also full of newspaper clippings, paint tins, books, recipes, bills, objects, and memories left by passing friends. Sometimes I spent the night there tending to my potted plants, or planting bulbs. It was a place where there was always something blooming, even during the coldest winters. These memories led to the realization of the series of works Band of flowers–Nocturne, 2021, which I presented in the Espressioni exhibition, at Castello di Rivoli, in 2022. Those canvases represent flash-visions of flowers at night, focusing on the tight harmony that binds stems and buds. In the small labyrinthine clearings which are not occupied by floral bodies, I inserted oracular words and phrases, imagining that the flowers spoke words of advice about the difficult coexistence between species on planet Earth. The space of the wild garden also returns in a different way in the performance Sogni I, in which a choir of women finds themselves singing along a stream of sulphurous water in the middle of a woodland. I chose that place, because it was a stretch of river that had been artificially channelled following the excavation of a sulfur mine owned by Montecatini Edison. The water was needed for the running of the factory, and in particular the storage department, the only one requiring tasks considered appropriate for women. The women in the choir appeared in the landscape enveloped in a spiritual and estranging aura, wearing some nightgowns that I had found in a family closet. In preparation for this work, I had invited some friends to paint and sew these fabrics with me, asking them to imagine the dreams of the bodies that had worn those clothes in the past. At the end, I also partially painted the choristers’ arms, faces and legs with clay and colored glitter.

As you mentioned earlier, My Heritage is located in a square which was violently hit by storm Alex, which in autumn 2020 devastated the valleys of the Mediterranean Alps, on the border between Italy and France. The painful memory of the flood brings us back to the theme of climate change and environmental crisis, confronting us with the urgent need to reset the ecological relationships that regulate life on Earth (in all its components, animals, plants, minerals)–a reflection that gently emerges in some of the works you have mentioned so far. But I wanted to ask you another question on this topic. What is for you the value of imagination, the potential of fantasizing and creating unexpected visions, within this scenario and against the immobilizing fear of catastrophe? The words of writer and activist adrienne maree brown come to mind, when she says that “we are in an imagination battle”: as we feed our desire and direct our efforts toward change–social, political, economic or environmental–we are trying to shape the unknown of a “future we long for and have not yet experienced.”

I was a child before smartphones came along, my mom used to read me children’s magazines to keep me entertained. Those stories, read aloud, created a constellation of images inside and outside of me, which connected me with the world. Writing and painting continue to teach me new ways to rediscover joy and wonder in front of nature, to play, and to imagine my life as part of it. I believe in the transformative chaos of love and although much still escapes me–not least the complexity of ecological systems, the environmental and climate crisis–I think that our planet can generate life in a myriad of unexpected forms. Therefore, describing our place and our path in the Universe in magical and imaginative terms represents for me an act of resistance against the damages that human beings have perpetrated against the Earth and other human beings. I believe that every body that generates images in their imagination is a body that carries intuitions and possible futures.

Your words bring to mind the texts of scholars such as Silvia Federici or Carolyn Merchant, who remind us how the agricultural societies of pre-Renaissance Europe favored a holistic and magical conception of the human body and of the body-world–of the environment. That type of thinking was able to contain the exploitation of bodies’ and land’s resources within certain limits, which were considered socially and morally acceptable. As we know, modernity has disintegrated that vision, leading to the rationalization and mechanisation of nature. This shift in paradigm, which laid the foundations of capitalism, came at a higher cost for those bodies that were oppressed because of their gender and class, racialized, persecuted for their sexual orientation. Very often, women’s bodies. Now I was thinking of all the female protagonists in your works, the skiers, the Malefate, the dreamers… your works articulate a universe of women’s voices, of women’s stories. But I would also like to ask you how you feel about being a young woman and a young artist today. In this historic moment, and also with the current Italian government, with the leader of a radical right-wing party as first female prime minister, “who has nothing to do with women’s politics.”

I’d say that my attraction to women and their worlds is driven by a magnetic and primordial energy, somewhat childlike. I love their sense of intuition and their capacity to share their creative life with other people. Making my work about the listening and resonance of female voices allows me to be a porous carrier of oracular and whispered points of view. I was thinking back to the reading of my birth chart that we did when you came to visit me here in Lisbon. It’s a way we have at our disposal to reach deep memories. When I think about what is happening in Italy and in the world, I struggle to explain it to myself. I don’t feel represented politically by the country where I was born. There are many questions and thoughts that pain me, from the landings of migrants to the prison conditions, to many other situations where lives are unprotected and silenced. However, I feel trust when I meet people who decide to fight injustice starting with the smallest and most daily gestures. I am reminded of my mother, who works as a teacher in a kindergarten in a town near Turin. This year there are many children in her class who come from families of varied cultural backgrounds; some do not speak Italian. One day I visited her at work and seeing the way they relate to each other, and with the teachers, was a precious lesson for me: a perfect mix of instinct, imagination, play, and love. I believe that nourishing our plasma, our lifeblood, to radiate new paths and to relate to the world in other ways, is a possibility that every person stores within themselves.

Going back to Limone Piemonte and your work there, I wanted to ask you something regarding the title you have chosen, My Heritage, which immediately struck me. “Heritage” is a word that refers to a narrative dimension which is transpersonal and generational, to something that has to do with traditions and a shared knowledge, that is handed down from person to person and creates community. But then there is that adjective, my–which I feel is very characteristic of your work–which brings out the unique and partial point of view of the individual. It reminded me of our adored Patrizia Cavalli writing about that “io singolare proprio mio” (my very own singular “I”): that sort of awareness that detaches the figure, distinguishing it from the background and making it come forward, at times even with a certain suffering… Can you tell me how this title came about?

I chose the title My heritage because it fell upon me. While the people of Limone Piemonte were telling me about the dynamics of storm Alex, which hit the town during the second lockdown in 2022, I gathered a lot of information on other major floods. Searching the archives for information on the November 1951 flood in Polesine, Veneto, I discovered that my own grandparents were among the 180,000 people displaced by the flooding of the River Po, which occurred at a terrible time, just six years after the end of the Second World War. Fiat, in Turin, “welcomed” most of the refugees from the flood of the great river as workforce. I thought of the title My Heritage because, similarly to what happened in Polesine, also storm Alex caused deaths and displaced people: climate change and environmental disasters are and will be a part of the individual and shared stories of many of us. Different stories; for this reason I have chosen not to use the plural adjective Our, because I don’t want to attach to others a narrative that is not theirs. However, I hope that anyone who comes across this specific story with the title My Heritage, can find their own way of feeling part of a larger one: it is an extended and collective my, because it echoes from person to person. While developing this work, I was thinking about the movement of bodies forced to migrate, about bodies bound by love, about bodies engaged in repetitive movements, about bodies that contain rivers and lakes. I wanted to place all these possibilities in the narrative space, modifying and synthesizing, in order to give the image a slow and cosmic flow.

From September 2022 you moved to Lisbon for a residency. To bring this conversation to a close, I wanted to ask you how this new place is entering your artistic practice, your personal archive. What are you working on at the moment?

At the moment I feel in a condition of “nomadic vitalism,” borrowing a term from the philosopher Rosi Braidotti. In Lisbon I live surrounded by young creatives who come from all over the world and work from their computers, seeking a communal dimension. For me it is a period dedicated to research and study, but also of silence and disconnection from the chaos of the work environment and social media. Among the new projects I’m developing, the Insurgent Maps are works with which I’m trying to elaborate what I would define as embodied psycho-geographies. They are stratified pictorial works, within the same painting it is possible to follow paths that trace different spaces and times. I imagine them as crossroads of stories that interconnect with each other. To create them I’m using old and new drawings, papers, poems and notes, which I assemble, going beyond the limits of the frame. I use words, colors and a lot of water, as I mentioned earlier, which helps me imagine how cultural flows mix with emotions, with the fluids that infuse the planet, with human and non-human bodies.

My Heritage has been funded by Fondazione CRC Bando Distruzione, on a scientific commission chaired by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev. The project was curated by a.titolo (Francesca Comisso and Luisa Perlo) and Andrea Lerda, and produced by association Art.ur.

Thanks to Angelica Bollettinari for translating this conversation into English.