The Shared Space of Oblivion

On Muna Mussie’s “Oblio / Pianto del Muro” for “re-creatures”

re-creatures is a public program of installations and performances curated by Ilaria Mancia, which has materialized since last summer in the outdoor spaces of La Pelanda and Mattatoio, as a network of activities open to the public that intertwine with each other free from any disciplinary boundaries, along with the Prender-si cura residency program for research and artistic production, the master in performing arts MAP_PA, and the series of free workshops Ricreazione.

re-creatures manifests as the tip of an iceberg, emerging through encounters with the national and international performative panorama. Artist Muna Mussie is among the protagonists of this new iteration of re-creatures which will inhabit Mattatoio first in May and then during the summer with a series of appointments unfolding the different aspects of the performative, where being with and cohabitating a space become central aspects of collective thinking.

Muna Mussie‘s practice has always crossed over the performative and the visual with particular focus on the dynamics of memory, the overlap of personal stories and historical facts, and language in its various connotations. We asked the artist to tell us a bit about the birth of her Oblio project, that unfolded as a site-specific installation in Parco Valentino in Turin, on the occasion of La Biennale Democrazia, a large exhibition project curated by Fondazione Sandretto Re Baudengo in collaboration with Black History Month Florence, a reflection on collective memory in a symbolic location for Italian colonialism—as Muna Mussie herself points out.

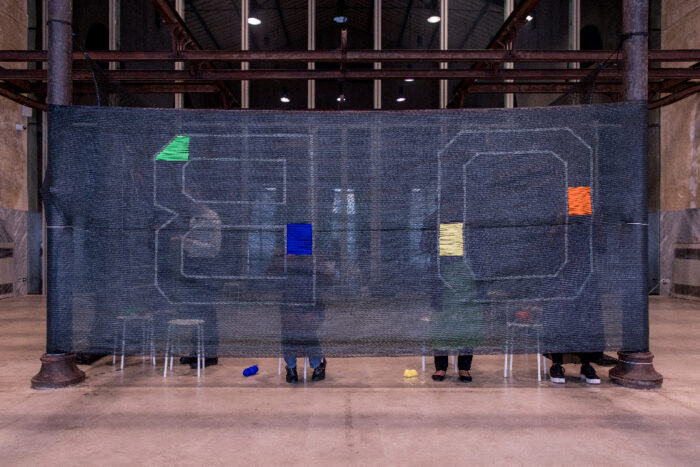

“My initial desire”—she says—“was to work on the concept of oblivion, an issue I was already busy with in a workshop I was holding in Milan. I had read the essay What Is A Nation? by Ernest Renan, in which oblivion is emphasized as a fundamental part of the creation of the identity of a people, so it is its removal, it is as powerful and creates collision. I therefore wanted to hold this question starting from the negative meaning of oblivion, in order to deconstruct it. I then decided to use embroidery and physically act upon the word ‘oblivion’, through the activation and deactivation of the word within the gesture of embroidery where form and content merged, and the fact that oblivion represents something that unites was rendered visible. This was also an opportunity to transfer an experience that, until then, I had carried out with a small group of people—in which each was confronted with his own personal oblivion on a portion of fabric equal to an A4 sheet—that is to say to a public dimension, where personal stories met history. Made with scaffolding tubes covered with construction fabric, the structure was positioned right in front of Castello Valentino, and its outline was drawn on the cloth. A symbolic sign to mark an environment where the people involved were engaged in the action of embroidery—as a space to live and recreate history, a construction site, a new home to evoke both construction and renovation of something; a space with an ever changing temperature, a continuous work if we want, an active and veiled nature within a predominant idea of both the visible and the invisible. Everything referred to the concept of oblivion as not static, but as something that constantly vibrates—like a ghost that wanders inside and outside of us.”

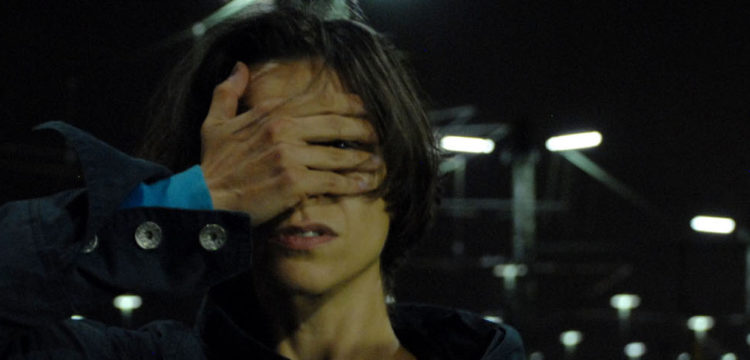

Among others, Muna Mussie is part of the Prender-si cura residency program for research and artistic production, now in its third edition. For the occasion, the artist has chosen to continue with her research on oblivion, thinking within a possible declination for the spaces of La Pelanda, where she is presenting the iteration Oblio / Pianto del Muro, carried out as a performance and installation. We asked Muna Mussie to tell us how her research was carried out during the residency.

“I wanted to continue working on the concept of oblivion and to find a way of practicing embroidery that would allow me to investigate different possibilities. I wanted to find a way to take back the work I’d done in Turin and bring it elsewhere. When thinking of Mattatoio, its events and its architectural structure, it seemed appropriate to expand the concept of history and think of a kind of oblivion that could include everyone. The idea of Pianto del Muro (the weeping of a wall) is very relevant to what the walls have seen and heard over time in that specific space, which is a former slaughterhouse. I imagined a space that can accommodate humans and non-humans and also account for the complaints of its walls. I thought of a structure that resembled that of a wall, one of the first references was the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem, a place which recalls a well-known violent history. On the one hand the wall evokes the idea of the sacred and, on the other, that of war, it is used both to protect oneself and to attack, it is a barrier that prevents any dialogue. We have been hearing about walls for a long time, as many have been built but somehow the news always comes like something new. This is obviously part of a broader repression mechanism which I’d like to underline the repetition of, by holding the gaze and giving a space to stop and look, to experience and take on this recurrence of history. I also wanted to allow the people who have collaborated with me to have a shared space where we can all cry together, and a time to dedicate to a lament, a certain sadness we might be ashamed of, which nonetheless grips us all. Well, here we can hold the luxury of manifesting and sharing.”

During her residency period at Mattatoio, Muna Mussie has in fact collaborated with various realities and artists active in Rome, connected to the hosting venue. One of these is Coloriage, a tailoring association that works with migrant and unemployed people. Thanks to them, Muna Mussie and the people involved in the project came into contact with the workshop’s participants who will be activating the installation, together with the artist, through the practice of embroidery.

“Embroidery—she says—does not seek beauty or technique, as beauty exists in the hand of those who act, even in their distortions.” This medium is very recurrent in the artist’s work, she encountered this technique years ago: “I first bought a digital embroiderer because I liked being able to transcribe some words in the form of embroidery, on my clothes and on those I embroidered for others. The dress always speaks, but the idea of embroidery has value even if it is not made by hand. There is a time of elaboration of the word that has its own importance and weight. It is as if the word were embodied directly on fabric. For me, embroidery was a necessary bridge to be present and integrated into history, to enliven it and make it accessible. My personal experience really needs to activate these devices because there have been geographical shifts, inasmuch as connected and disconnected stories which need to find their own dimension. In order to feel something that happened apart from me, I need to switch on certain stories to say that I am there too, that there are contingencies that include me and in which I want to feel active and present—not just a mere spectator.

This action of the needle that metaphorically pierces the veil of reality and appearance and brings something to light, something that has been forgotten or that has not yet been thought of–this is an image that comforts me and that I feel close when I perform the action of penetrating and puncture the fabric. Then the thread comes out and in repeating this action a story or a landscape is drawn. When I use embroidery in workshops, I always try to create a dimension where I can freely provide those who participate with very simple notions. It is about experiencing a kind of intimacy made by the relationship with your needle and thread and with your portion of fabric, within a shared space. The exchange takes place in activating an action on an emotional and energetic level that also allows certain relational tensions to dissolve. It is a spontaneous mode of dialogue, it might be a sentence surrounded by a lot of silence. Embroidery does the speech, the word slips are countering the action’s intensity.

During the residency, the artist collaborated with visual artist, musician and sound designer Massimo Carozzi, who accompanied her on the sound aspect of the work. “The people who participated in the embroidery workshop,”—she recounts—“lent us their lament. With Massimo we have collected several modalities of it. We started with the word ‘oblivion’ and asked each participant for their own meaning of oblivion to find another word that was close to this personal vision. We then brought this word to a breaking point, to make it move away from its meaning by turning it into a sound that no longer needs to be said or explained but which comes out as a vocal sonority.”

Simultaneously to Muna Mussie’s residency, one of the workshops of the Ricreazione was conducted by musician Simone Pappalardo and singer Claudia Ciceroni. From this immediate proximity, a new collaboration emerged: “the work we did with Simone and Claudia was important. We took part in Claudia’s working sessions to lead the participants into this lament we were already investigating, and in addition to the individual recordings, we also got the chance to work on a choral version. For obvious reasons, the indications were to repeat a word until exhaustion, so as to lead bodies into another dimension. Right until it fades, a lament is indeed a repetition and is connected to oblivion as an action that leads to looking several times and rethinking a memory until it naturally vanishes.”

At the end of our conversation, we asked Muna for her own definition of oblivion: “I am convinced that I live more in oblivion than elsewhere, I am completely immersed in it and it is a dimension in which I am at ease. The question of oblivion pushes me toward action, as a strong urge to investigate as a possible landscape. I feel that this being in oblivion waiting for something is a condition that unites many. For me, oblivion has to do with the future and for it to become one it must be activated, rethought and moved.”