The Post is Over

A conversation with Ben Vickers on Postinternet, art market, artificial intelligence, worlding and radical reorientation of culture

This conversation is part of the upcoming Donato Piccolo’s monographic catalogue, curated by David Rosenberg and Valentino Catricalà.

Valentino Catricalà: The Postinternet era is over. The post is over. Even though we are still living in a kind of post-post-something, today we are facing a different contemporary art world—and world at large—compared to ten years ago. The Postinternet has been described as an attempt to give a new vitality to a declining trend, that is the Net Art. Relocating and giving new vitality to Net Art meant to give physicality to something that was not physical. This inevitably lead to an involvement in the market of galleries, institutions, and so on, that destroyed the critical basis of Net Art. Perhaps, Postinternet was killed by Postinternet itself. You know it very well since you were part of the Postinternet movement since the beginning, and also have been one of the first ones to somehow refuse this term.

Ben Vickers: It’s funny because when I’m invited to related events, I feel this Postinternet obsession, while to me it feels like past. There was a period of time when people wrote often to me to discuss about Postinternet. There are a couple of reasons I chose to give it up and take distance. Nevertheless now I can only speak from my personal experience, with no real authority.

There was a defining moment for me, that shifted my perspective and relationship to the term, that was at the READ/WRITE at 319 Scholes exhibition in New York in 2011—a combination of this online platform run by Parker Ito and Caitlin Denny, bringing together for the first time a group of people in their early 20s, who had been good friends online and collaborators, many of whom were meeting in person for the first time. It’s almost a decade ago now!

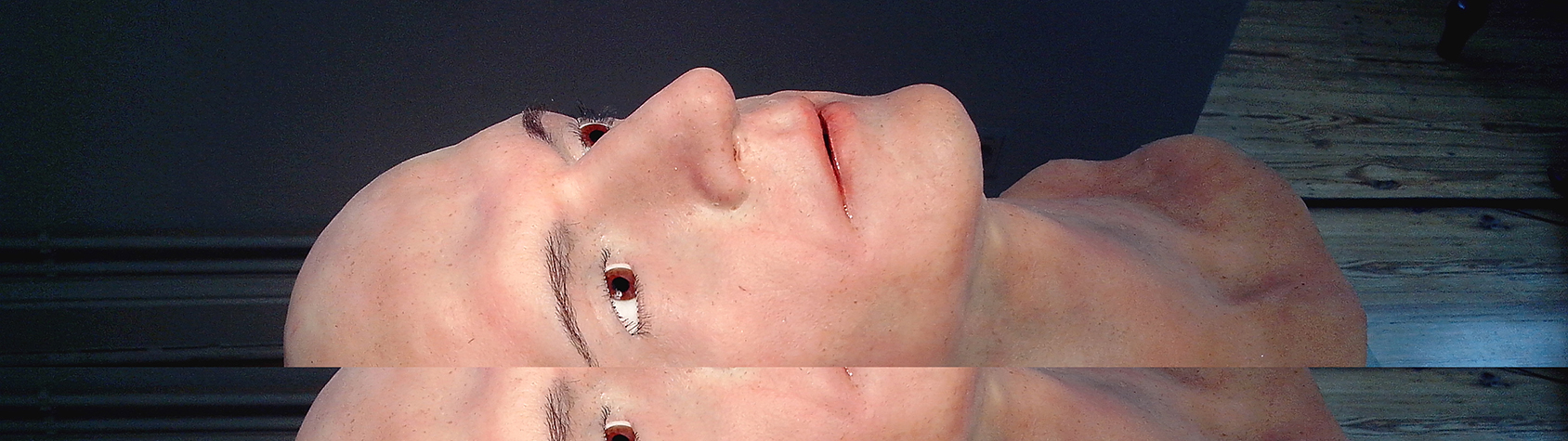

Eva and Franco Mattes, Dark Concept, 2014

To give a better idea of the context, it’s important to note that at that time there was only one blog on the internet that was aggregating contemporary art, namely vvork run by among others Oliver Laric and Aleksandra Domanovic. This was a very small concentrated international community and these people became my friends—I felt there was necessarily nobody else to be making work with, at art school or within the scenes I was connected to in the UK. So everybody came together. I was happy, but when I finally got there, it was like a funeral. At that point, it felt as that moment defined the end of a certain line of investigation.

Looking back, I guess the main reason why I really separated myself from Postinternet was that meeting, as I realized that I conflated the political intention and interests of those people with the technology they were using. When we met in real life, I realized that there was a total divergence between what I was interested in, what motivated me, and that a desire towards a decentralization of the art world was in many ways coincidental. I entirely renounced my participation in it as a movement when many artists made total capitulation to the marketplace, which heavily impacted the form of the work. People went from producing very immaterial works bound to collaboration, friendship and experimental ideas to a practice relocated into the gallery space. This entirely displaced and precluded the possibility of an art without the gallery system or white cube, so at that point I didn’t feel like that. My practice back then was increasingly dematerializing so it was not even serving the work online anymore, as that place had already begun to become saturated with the advent of tumblr and the shutdown of delicious. I think probably around that point I stopped producing works that were in anyway legible to a public, and dispersed into a networked practice, that prioritized network effect over formal composition or conceptual tropes.

Ed Atkins, Ribbons, 2014

The contemporary art world is changing fast today. It may not look evident, but I think the main reason is the spread of technologies in our lives, costumes and within artistic practice. Six or seven years ago we were able to talk about concepts such as media art, new media art, net art and Postinternet art as separated from the contemporary art world, but today technology is a common language. Going to a Biennale or to any other similar event today means to see artists using technologies, internet, media archaeology, etc. Exhibitions about robotics and artificial intelligence are everywhere. Many of these events are devoid of real research. If we look at the past, we realize that all of these topics are not new at all. Since many years artists are dealing with big issues such as the future of human life, worldwide surveillance, etc. We need new theory, new criticism and new histories.

Yes, I agree. As a teenager I grew up looking at net-art and being obsessed with groups like Ubermorgen and Eva and Franco Mattes but then at the same time that type of artistic practice wasn’t entirely disentangled from other forms of online production. In fact, groups like etoy preempted movements such as Anonymous. net.art was tied up to different forms of political activism, and for me that was a very important element to understand how art was finding its place in the world during early cyber culture. When I was making works, I was building references to these practices, and now it is very complicated to try to think about the relationship between art and technology, whether it defines a movement or whether it defines a generation. This is particularly complicated within the canons of art history because the big collections have never really collected that historical moment, the fact that Ubermorgen’s vote.auction doesn’t appear in a single museum collection, seems to be a shocking omission—particularly given how accurately they preempt how we got to where we are now societally, fake news and so on. Art movements are useful for defining a moment, as it’s useful to have terms and language that enable people to develop a discourse together and to create a flashpoint where they can meet over common subjects. On the other hand, I think that the market and attention the economy of the art world can take advantage of these discourses, as trend visibility has a very strange effect on artistic production, in a sort of cargo cult mentality. There’s such a drive towards success for art now, and for practices to speak directly to the market, that creates this extreme professionalization.

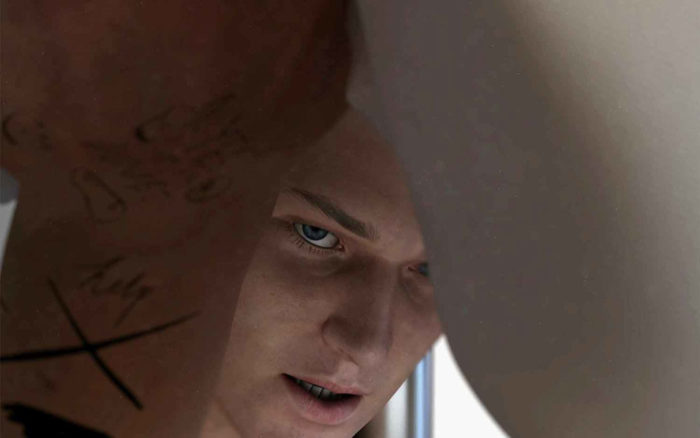

Ian Cheng, Emissary, 2017

Yes, I think that today we have to change our idea of “critical attitude.” In particular, we need to change the way in which we identify this term from the sixties to the nineties circa. Big companies (i.e. Microsoft, Epson, Google) are nowadays engaging with the arts by organizing artists’ residency programs or including artists in broader projects. The mass production of new devices (immersive, augmented, etc.) requires new creative ways of experimentation, and this is why they want artists. In my opinion, this opens two different possibilities: either the artist takes the risk of becoming part of companies’ mass production, although being overwhelmed, or the artist’s creativity could eventually orient the mass production toward more ethical ways. I am not sure I am right, but this is what I am trying to do collaborating with Epson, HTC Vive, Oculus, etc. I’m trying to make the capitalistic production of technology more ethical, by engaging with new markets and shaping a new kind of criticism.

For a long time I was not interested or comfortable in working with corporations to produce any kind of artistic endeavor. That changed in the last couple of years—partly by necessity of being part of an institution. And its interesting to consider the ethical complexity here, particularly in an institutional context, often one comes up against this contradictory ethical code, that states: if we collaborate with these companies then they are going to compromise and instrumentalize the work! My response to this is to highlight the fact that art, which is made public in the moment of its making, has been and will likely always be shaped by the dominant economic paradigms of the moment. The issue here though is that there is too short a term view, that makes a claim to a ‘pure’ form of integrity, that I simply cannot see. The majority of art being displayed at the moment is a throwback to aristocratic tastes and desires. This leads to a particular prioritization of artistic forms, remaining primarily painting, but if the collector system as we know it is to extend to other tastes, then the more technological one can also be included within this frame. The reason why exhibitions take the form that they do, the reason why you have private openings, dinners, and so on is to serve the infrastructure of an aristocratic class.

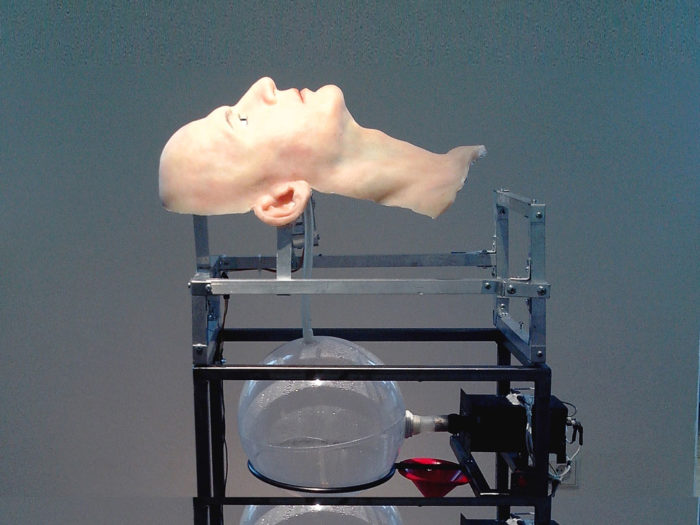

Donato Piccolo, Leonardo sogna le nuvole, 2014

So for me, the difference between the corporate vs the aristocratic, can be the splitting of hairs, there is not really any position outside of capital, other than producing a practice that is totally illegible to those systems and that is not something that’s going to be recognized within this moment and it is not going to be part of any of those trend circles, something that has been referred to in the past as immediatism. Every economy you enter in terms of art production is compromised. Sometimes it is just not visible what that compromise is, because you could be two or three generations out and you are not necessarily considering those different kinds of market forces. In terms of what the opportunity is right now and why I think it is interesting to work with companies requires some consideration of how different economies have shaped the arts to date. From an aristocratic world in which monarchy and church funded the arts, to the transition to Nation State where you have public funding, the antagonism between corporate funding and public funding is set up. There’s a certain expectation that public funding produces a condition of non-instrumentalized artwork. If you look at movements like Relational aesthetics, and you look at the kind of European funding models and the agenda set down through the Blairite era through institutions such as Tate, and you look at the correlation between the practices that emerged in that moment and the funding mechanisms made available you will notice there is a direct correlation to what was given the greatest platform. As people who pay attention to the shaping of art history, we know that there are many movements and moments that were not well funded like the net-art movement, new media etc. These are not well represented in the canon because there wasn’t the same level of capital investment and they never paid lip service to the tastes of dominant economies. It’s interesting when you look at it like that. Right now there is a unique set of opportunities. I’m not somebody who is in favor of perpetuating the violence of the Nation State as an organizing form, so I also do not believe culture should be a tool for the Nation State to express itself and thereby contribute to the project of globalization. I find it deeply compromising. There are strange opportunities within emerging relationships with corporations that can be understood through the writing of people like Benjamin Bratton, as these organizing forms become new types of mega-structures of transnational governance and in the same way, people may want to participate in a State-funded art system. It may also be necessary to influence what people call the “stacks” through participating in the artistic expression of those forms, for better or for worse.

I believe artistic acts or gestures to fail within this context when they simply serve as content on a pre-defined technical platform such as VR, AR, and others—instead new works should be seeking to shape and define these technologies, otherwise it is simply sophisticated marketing. Instead, it is important to situate artistic practice upstream of the products that are derived from technical R&D. To form a symbiotic relationship between advanced research and artistic practice.

Ian Cheng, Emissary, 2017

I agree with that. Artists are more and more frequently working in team with engineers and technician, that is why the materials used are more complex. The important thing is that artists using technologies, working with companies, technicians, etc, keep being capable to bring new visions and concepts to the philosophical and sociological debate. This is what I meant before by saying “ethical.” In this environment, which is more and more dominated by technologies, we need new concepts in order to look at the complexity we are facing. Complexity related to technology today is often connected to some 80s’ terms such as posthumanism and transhumanism. These concepts belong to an old vision where the natural body is seen as something weak, something to empower through technology. It is a very anthropocene oriented point of view. I am more interested in artists working toward an idea of overtaking the anthropocene. I have been inspired by the latest studies on the intelligence of plants, the new studies on bacteria and genetics and the concept of animality. Donna Haraway pointed out the idea of the Cthulhucene in her last book, describing with this concept the new world the human being is about to live in a new idea of nature (she speaks about Gaia). I’m thinking about artists such as Donato Piccolo in Italy or artists such as Ian Cheng with his idea of worlding.

I also think that it feels like an expression of something new—but I also feel that Haraway and many others that are articulating a response to this New Wyrd, are channelling one aspect of a much large story.

In my thinking I’m really influenced by Terence McKenna, a prophet of the second psychedelic age, who says this thing about the plot twist of the XXI century being what he refers to as an archaic revival, that ideas, concepts and civilizations that predominantly the West colonized, denigrated and got away with during the XIX and XX century are returning through a myriad of forms and experiences, to make an intervention. The figure of the shaman, the animist worldview is becoming stronger and stronger than perhaps has ever been before. Whether it is the spread of yogic practices, the spread of ayurvedic medicine coming from India, it is something that was really put down during the colonial era and was resuscitated by people like Deepak Chopra, as the spread of ayahuasca and Marie Kondo, are all in some ways symbolic within this shift. This strange kind of drive where the link between the technological and mythical comes to a point of schism. The overly deterministic and rational nature of machinic culture as we have known it for the past century, or perhaps longer, comes to an end. Data fails us in a moment of complexity and deep weirdness, and in its place systems of prophecy rise again. Whether it’s manifested in an obsession with astrology, tarot, or other practices with ancient roots, I think that we’re seeing a manifestation of this all across the arts. An animist worldview in which everything is alive also allows for a better framework for understanding through technology the emergence of intelligence into systems around us, and gives us back tools that allow us to communicate with that shift.

Intelligence is a complex concept. What is Intelligence? If you see it through biology, you have a completely different idea to what genetics is pointing out, which differs from the engineers’ idea of intelligence. There is not a unique way to conceive technology. The question is: “what do we want from what we think intelligence is?” As Simon Penny has pointed out, “asking a computer to discern the best between two chocolate cakes is a far more challenging task than playing chess.” I still think that we can get some insight by artists. This is what Hito Steyerl, Ed Atkins, Cecil B. Evans, and many others are trying to do today, as many artists have done in the past. Maybe also engineers should look at them.

I’d say a couple of things on that. The first is that I think that the notion of artificial intelligence is going to be with us at least for the upcoming century and that it’s not a topic that’s going to go away because we’ve reached a point now of convergence with a set of technologies and discoveries. That means that it will continue to be an existential problem for the human species—to define what we are in relation to it. That’s not to say that we’re headed towards anything that resembles a singularity point. Hito Steyerl makes this good point because what we fear is not super-intelligence, but rather stupid intelligence, so actually seeing the impact of very dumb artificial intelligence in society and governance, whether it is a bot army that’s swaying public opinion or something more benign. It doesn’t need to be a super-human entity that’s going to displace the human species to have significant impact. And then the other thing I would say is that I think that the reason we have so much art and exhibitions and cultural engagement is the existential issue, and the fact that somehow art always deals with the existential strain.

But also the centre of gravity for intellectual inquiry and thinking, those forces and energies that were historically capable of producing and transforming the future have evacuated the art world. And the current obsessions with AI and technology more generally is an expression of that awareness on the side of institutions, curators and individual artists, with a strong desire to catch up with other spheres.

In many ways it is real sad for me that many friends who I still consider to be great artists have exited the art world, in favor of other industries, because they actually allow greater freedom to express and experiment with their ideas on governance as an artistic form.

And it’s likely that we will see an increase in this brain drain from the arts if we don’t see a major reformation in the way in which artistic institutions are constructed and what they do. We’re going to see entirely different cultural spheres emerge and they’re going to produce something that cannot be anticipated by the more traditional artistic spheres, something that has the potential to eclipse the dominant ideologies in current cultural production—something akin to Hermann Hesse’s Glass Bead Game in his radical reorientation of culture, which thereby will force a fundamental change in the construction of our current institutions…