The Poetry in the Cracks of Language

Challenging the notions of white cube and black box

After Julie Monot’s investigation on the green room, Gilles Furtwängler turns the white cube into a performative space. The following collage of theoretical and descriptive fragments, poetry and documentation gives some insights on Furtwängler’s approach to his latest work Un Peu Squeeze, curated by Elise Lammer for the research platform Alpina Huus, now on view at Arsenic, Performing Arts Center in Lausanne. The quotes on theory are excerpts from Susan Sontag’s essay on Performance Art (2007), and Hannah Arendt’s introduction to her The Life of the Mind (1971).

Poetry—Excerpt from Bastard, hoody, bastard, hoody.

Gilles Furtwängler, 2016–2018

“Bastard, hoody, bastard, hoody.

Beany, idiot, vermin, broken arm.

Bastard, hoody, bastard, hoody.

Beany, idiot, looser, crowbar.

Bastard, hoody, bastard, hoody.

Beany, idiot, vermin, broken arm.

Bastard, hoody, bastard, hoody.

Hello everybody, I had the envy to share this song with you, written with the words of certain of my neighbors, very active on our Whatsapp community group. (Peace)

Beany, idiot, looser, threat.”

Gilles Furtwängler, C’est inacceptable de détruire des magasins, 2016. Acrylic on papier, 46x61cm. Image © Julien Gremaud

Context—Un Peu Squeeze

The expression “Un Peu Squeeze” was used by Elise Lammer to suggest a lack of time before a deadline, a rather typical situation when working on an art exhibition. A clumsy “frenglism” or “franglais”, the title conveys a sense of general confusion, not only through the misuse of an English word by a native French speaker, but also because it translates a form of labour, whose rhythm and language are profoundly affected by globalization.

Subject—Gilles Furtwängler

The work of Gilles Furtwängler (*1982 Lausanne, lives and works between Lausanne, CH and Johannesburg, ZA) seeks to extract the poetry hiding in the cracks of language. Using written and spoken words, his work highlights (or provokes?) the serendipitous collisions that so often take place when manipulating language; mistranslations, rhymes, neologisms, nicknames, puns, oxymorons are only a few examples of the figures the artist is using to produce his mischievous literary arrangements.

Theory—Susan Sontag, “Performance Art”

“That’s the kind of language a child might write in a letter home. In what I call a theory of the comic—it isn’t the theory of the comic, I don’t know what that would be—I’m not describing the main tradition of the comic as embodied in language, in words. I’m not describing the main tradition of comic discourse, but I think I am describing the main, or a main, tradition of the comic as a performance, a performance which is often rather short on words, which might in fact be mute, and largely expressed in physical behavior. The tradition of the comic that I’ve described inductively is, for instance, very well embodied in silent comedy.”

Context—Words

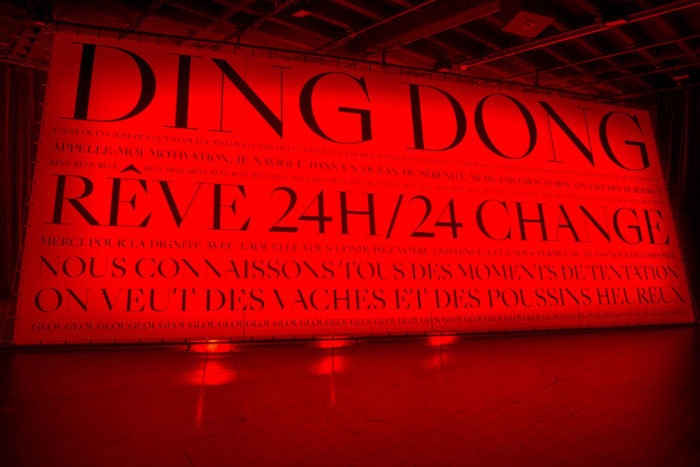

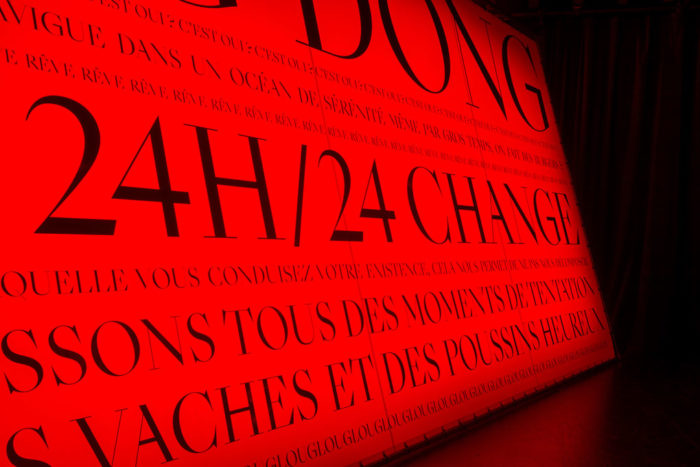

In the work of Gilles Furtwängler sentences and words are used for their semantic value, but they’re also assembled for their formal quality, as visual cues potentially triggering new interpretations through form and texture. As such, there is a strong connection to Concrete Poetry, an artistic movement that emerged in the 1950s proposing to visually structure, interrupt or degrade the combination of words in order to create alternative meanings to the viewer.

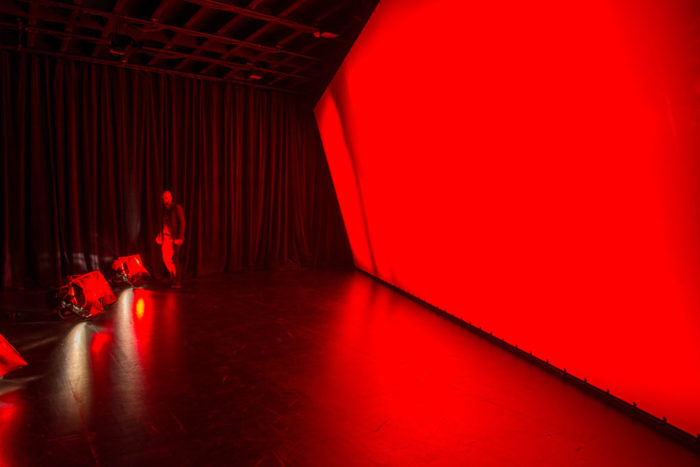

Alpina Huus x Arsenic: Gilles Furtwängler, Un Peu Squeeze, at Arsenic, Contemporary Performing Arts Center, Lausanne.

Alpina Huus x Arsenic: Gilles Furtwängler, Un Peu Squeeze, at Arsenic, Contemporary Performing Arts Center, Lausanne.

Poetry—Greetings, Gilles Furtwängler, 2010

“I am unique, I demand respect for that.

Hello.

Raised fists are old fashioned.

We want to work but we are as bored as dead rats.

Greetings.”

Theory—Hannah Arendt, The Life of the Mind, 1971

“Heidegger, whom Camap singled out for attack, retorted by stating that philosophy and poetry were indeed closely related; they were not identical but sprang from the same source—which is thinking. And Aristotle, whom so far no one has accused of writing ‘mere’ poetry, was of the same opinion: poetry and philosophy somehow belong together. Wittgenstein’s famous aphorism ‘What we cannot speak of we must be silent about,’ which argues on the other side, would, if taken seriously, apply not only to what lies beyond sense experience but even more to objects of sensation.”

Context—Space

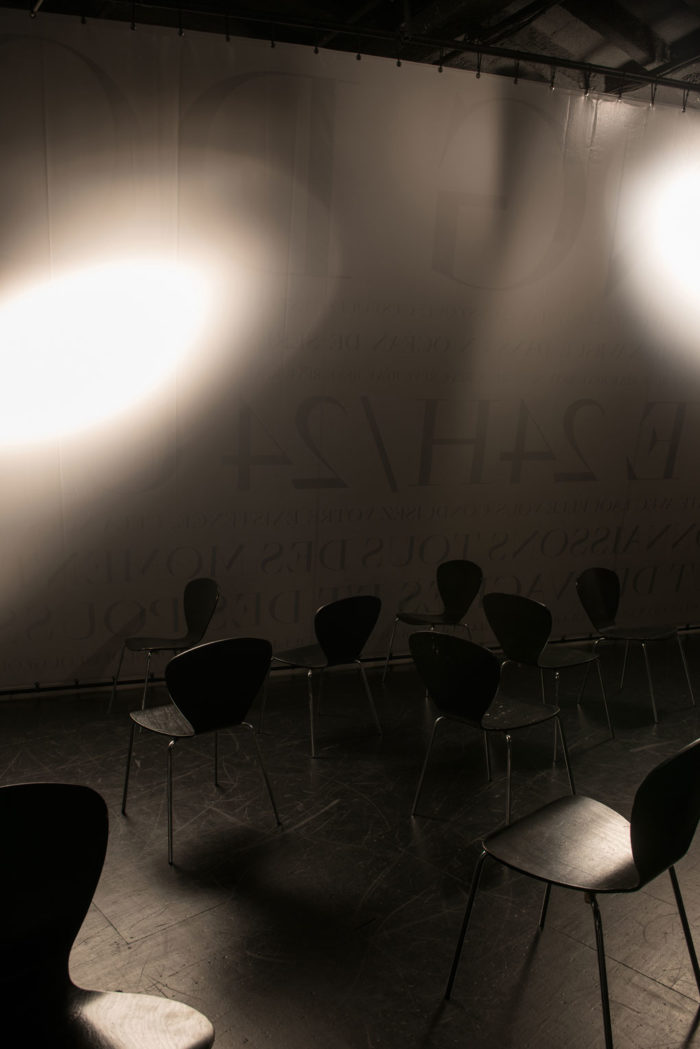

Since January 2019, Arsenic, Contemporary Performing Arts Center, Lausanne, is regularly hosting exhibitions of visual artists concerned with the relationship between performance and domestic space. During this project, curated by Elise Lammer for Alpina Huus, the artists are invited to work across the various performance halls of Arsenic, challenging the notions of white cube and black box.

Work—Installation

Among other things, the impact of neoliberalism on language lies at the heart of Furtwängler’s new installation, which consists of a hand-painted 9 x 4 m drop cloth. Hung across the space, the monumental structure—the only artwork on view—serves as a divider, but also as a temporary wall, behind which the artist is periodically performing a selection of texts from his repertoire during intimate reading sessions.

The experience of Un Peu Squeeze is intrinsically performative: inevitably one draws mental images when seeing, reading, whispering Furtwängler’s painted words. The artist doesn’t aim at predicting any mental choreographies, but rather prompts the viewer to let emerge an experience of shifting yet interlinked associations.

Alpina Huus x Arsenic: Gilles Furtwängler, Un Peu Squeeze, at Arsenic, Contemporary Performing Arts Center, Lausanne.

Alpina Huus x Arsenic: Gilles Furtwängler, Un Peu Squeeze, at Arsenic, Contemporary Performing Arts Center, Lausanne.

Theory—Susan Sontag, Performance Art

“The theory of knowing that is relevant to the comic is essentially a theory of non-knowing, or pretending not to know, or partial knowing. One of its illustrations might be endless enumeration of all possibilities, which would include being x and being non-x, and these discussed sequentially, as if what is being proposed is the equivalence of all; the leading traits would be cheerfulness, content, and a sense of completeness.”

Poetry—Excerpt from Bastard, hoody, bastard, hoody.

Gilles Furtwängler, 2016–2018

“Mmmmmmmmmh, I am starving.

Violence owns.

Violence owns.

Freedom haunts.

Freedom haunts.

Violence owns.

Violence owns.

Freedom haunts.

Freedom haunts.

Violence owns.

Violence owns.

Freedom haunts.

Freedom haunts.

Violence owns.

Violence owns.”

Alpina Huus x Arsenic: Gilles Furtwängler, Un Peu Squeeze, at Arsenic, Contemporary Performing Arts Center, Lausanne.

Alpina Huus x Arsenic: Gilles Furtwängler, Un Peu Squeeze, at Arsenic, Contemporary Performing Arts Center, Lausanne.

Context—Sound

Humour is what first comes to mind when reading onomatopoeia such as “Ding Dong”, but the tolling of this conceptual bell is only a strategy to capture the viewer’s eye and invite them to read further. If absurd at first, upon closer inspection, the text that unfolds is actually loaded with emotional and political content. Ecological discourse is juxtaposed with symbols of mass-consumption, while patronizing rhetoric is coated with the typically well-meaning speech of privileged classes. As if breaking the spell, more onomatopoeia is repeated endlessly at the end, until the eye is free again.

Theory—Hannah Arendt, The Life of the Mind, 1971

“Nothing we see or hear or touch can be expressed in words that equal what is given to the senses. Hegel was right when be pointed out that ‘the This of sense . . . cannot be reached by language.’ Was it not precisely the discovery of a discrepancy between words, the medium in which we think, and the world of appearances, the medium in which we live, that led to philosophy and metaphysics in the first place? Except that in the beginning, it was thinking. in the form either of logos or of noësis, that was held to reach truth or true Being. while by the end the emphasis had shifted to what is given to perception and to the implements by which we can extend and sharpen our bodily senses. It seems only natural that the former will discriminate against appearances and the latter against thought.”