The Poetic Cartography of Resistance

On Liên Hoàng-Xuân’s “Qasida: The Impossible Journey from East to West”

Invent hope for words. Create a cardinal point or a mirage that prolongs hope and sing, for beauty is freedom […]—Mahmoud Darwish, Counterpoint, Homage to

Edward Saïd, Le Monde diplomatique. Translated by Julie Stoker, January 2005

For her exhibition at Galerie Fahmy Malinovsky in Paris, Liên Hoàng-Xuân unveils Qasida: The Impossible Journey from East to West. Rooted in an ancient Arabic poetic form known for its monorhyme structure and themes of longing, love, and loss, the qasida provides both inspiration and a structural framework for the exhibition. The exhibition invites viewers to inhabit its fractured geographies. It encourages them to let their gaze linger and imagine a world where fragility holds its ground. At the heart of Hoàng-Xuân’s practice lies an enduring preoccupation with migration, displacement, and the ways bodies and landscapes are imprinted with the weight of histories. Building on this foundation, the exhibition unfolds as a journey, both intimate and expansive, where each work becomes a fragment of a larger narrative.

At the heart of Hoàng-Xuân’s practice lies an enduring preoccupation with migration, displacement, and the ways bodies and landscapes are imprinted with the weight of histories. Visiting Liên Hoàng-Xuân’s studio in Paris felt like stepping into a space alive with transformation, a quiet yet vibrant anticipation as works began to take form. During an open studio day, the evolution of her pieces became evident: landscapes layered with the weight of inherited stories and material choices that whispered fragments of a larger narrative.

As the day of the exhibition approached, Hoàng-Xuân shared her reflections with striking authenticity, recounting tales of the lands that shaped her and the voices that echo in her memory. Her work does not merely present these geographies; it embodies them, weaving them into tangible expressions. Through the alchemy of her production of works, the space of the gallery invites the viewer into an intimate dialogue with the textures of memory, history, and belonging. Her “haikus,” are gilded woodcuts that could symbolically remodel fragments of history into poetic artifacts, bridging the personal and universal. Each engraved mark feels deliberate, as though carving fragments of memory into the material itself. These works, engraved with motifs and fragments of text, seem to hold time within their surfaces.

The exhibition stands as a hymn to displacement and survival, balancing visual poetry with incisive critique. Its power lies not only in the boldness of its themes but in the urgency of the voice it carries. This is a voice of resistance: one that speaks softly yet refuses to be silenced. It brings together the timeless poetic traditions of the Arabic qasida and a daring contemporary visual language. Copper, wire, and woodcuts serve as active narrators, with each material embodying a delicate tension between vulnerability and strength, connection and constraint. Through her visual storytelling, Hoàng-Xuân draws on Arab and Oriental popular cultures intertwined with fragments of modern industrial aesthetics, challenging the occidental narrative of dominance.

In Hoàng-Xuân’s work, the qasida transcends its poetic origins, evolving into a structural and thematic framework. Like the ancient poetic form, the exhibition unfolds in cycles of loss, migration, and reclamation. Each work demands an active gaze from the viewer, drawing them into an atmosphere of introspection and resilience. This reflective cadence permeates the materials Liên employs, copper and wire, which transform into storytellers themselves. These forms extend into sculptures that depict subjectivities navigating fictional geographies, amplifying the artist’s exploration of collective memory. Complementing these are video-fictions that draw on the televisual aesthetics of her native lands, creating a fragmented yet cohesive critique that blurs the boundaries between the personal and the shared.

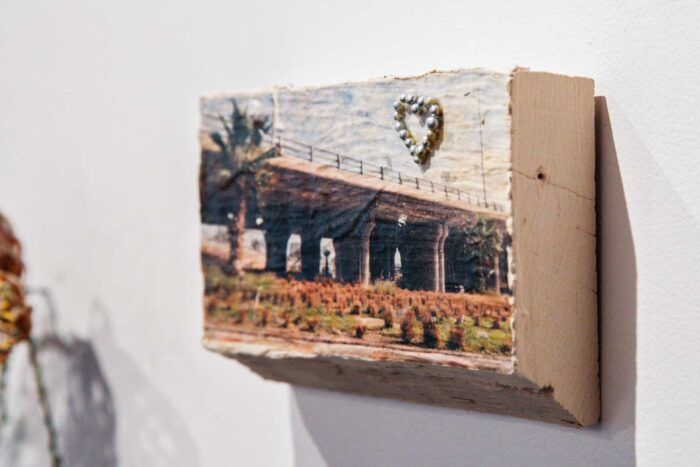

One of the most poignant expressions of tension between beauty and artifice emerges in the installation Al Nassib, a term meaning “destiny” or “fate” in Arabic. Here, landscapes of unfinished structures and abandoned buildings hover in a haunting liminality. These spaces, caught between presence and absence, construction and decay, pulse with quiet defiance. In Al Nassib, the narrative unfolds as an ode to forgotten spaces, echoing the melancholic song of a wanderer before embarking on an epic journey. Images transferred onto wood depict forgotten places and the people who inhabit these regions. These territories, though peripheral and seemingly mundane, carry a quiet poetry in their desolation. They capture the raw interplay between nature and human intervention, where sand and earth meet the stark impositions of modern architecture. These views, imbued with a sense of temporal stillness, evoke both the inevitability of change and the fragility of what remains.

This defiance is mirrored in Liên’s cable-crafted artificial flowers, whose delicate forms juxtapose fragility against their industrial materiality. Together, they invite an intimacy that unveils intricate worlds contained within their fragile boundaries. Each bloom embodies a paradox: its apparent fragility concealing an undeniable strength. This interplay between delicacy and resilience lingers, imprinting itself on the viewer’s memory. The defiance extends into the intricate details of the artificial flowers, whose designs echo the same tension between vulnerability and endurance found in the landscapes of Al Nassib. Their design recalls the decorative traditions seen during significant social events, particularly weddings and other Mediterranean celebrations, where objects become silent storytellers.

Kitsch, often dismissed as mere aesthetic flourish, emerges in the exhibition as a tool for subversion. Through heart motifs, pastel tones, and decorative objects, Hoàng-Xuân critiques societal constructs with playful irony. Her deliberate use of ornamentation engages in a dialogue with spiritual traditions that celebrate excess as a form of reverence, challenging the boundaries between artifice and authenticity. These elements compel viewers to confront their assumptions about beauty and value, while seamlessly bridging modern critique with cultural spirituality. This tension provokes an unsettling discomfort, urging audiences to question the systems that dictate aesthetic and cultural norms. By reimagining kitsch as a critical language, Hoàng-Xuân invites visitors to engage in a profound reflection on societal structures and the politics of representation.

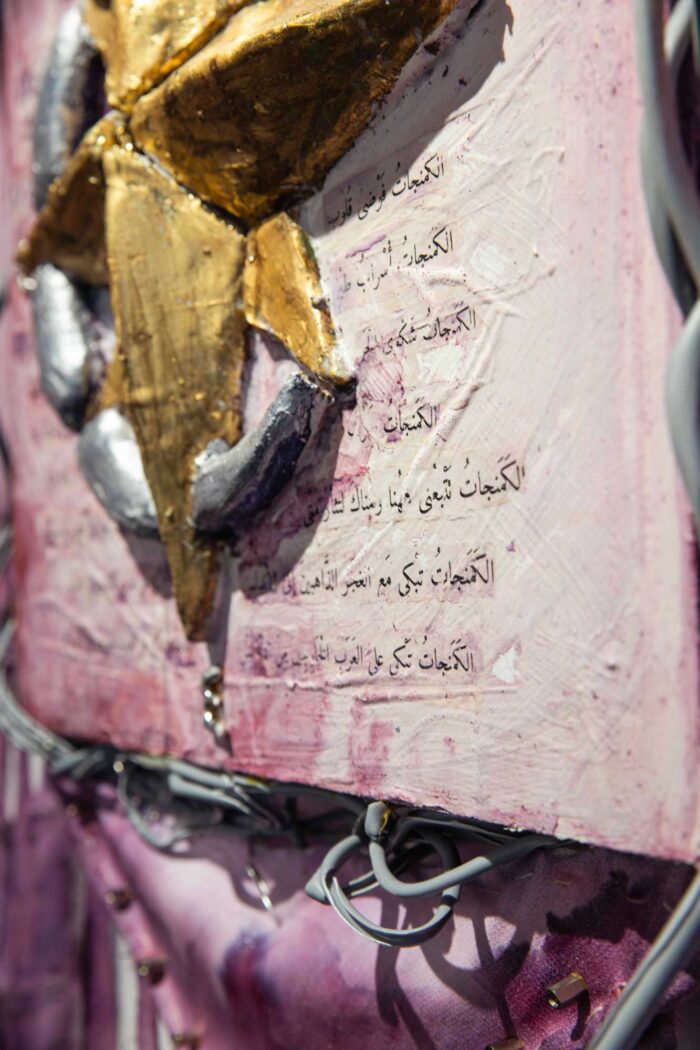

At the conceptual heart of Qasida are the cardinal points, a series of sculptures that both anchor the exhibition and disorient its viewers. Representing South, East, West, and North, these works delve deeply into the politics of geography and belonging. The South radiates an unsettling pink glow, illuminating oil-streaked lilies entwined in barbed wire, a visceral evocation of relentless exploitation. In contrast, the West looms industrial and forbidding, its taut cables embodying systems of control and displacement. The North juxtaposes withered flowers against vibrant blooms, both entwined in the same barbed wire, offering a striking image of continuity and transformation.

The East sculpture, subtle and enduring, conjures the image of a kite resisting the wind. Muted pink tones suffuse the piece with a sense of vulnerability, a fragile yet unyielding presence that encapsulates the exhibition’s resistance to erasure. Through its fractured geographies and fragmented materials, the exhibition evokes a world profoundly shaped by colonial and industrial excess, urging viewers to contemplate the enduring cycles of exploitation that have defined lands and histories.

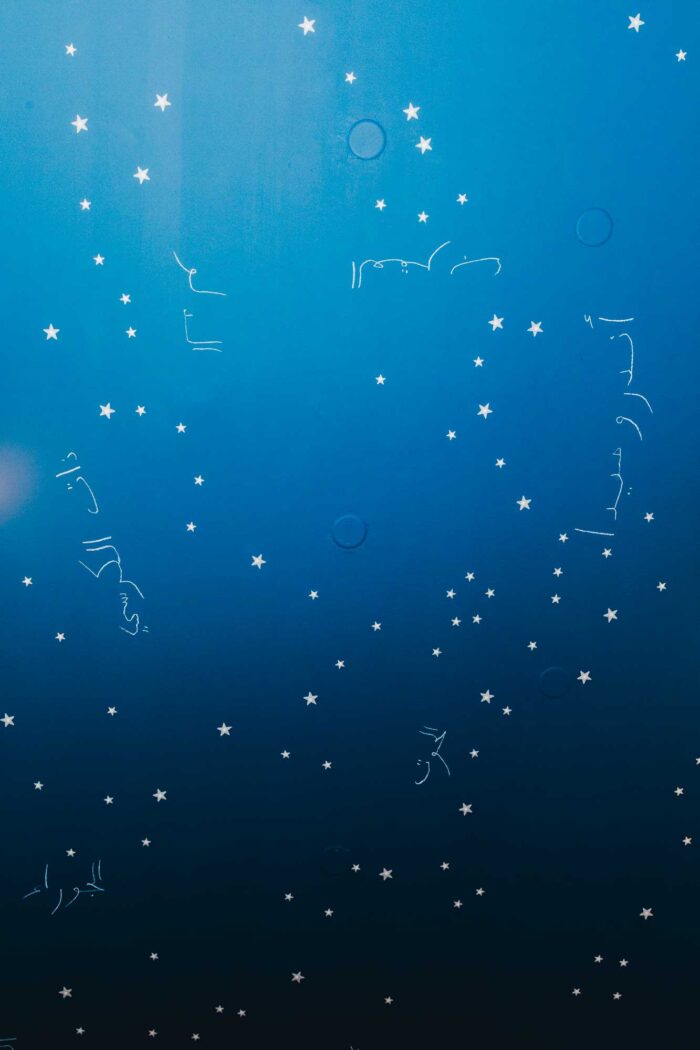

The ceiling above the gallery radiates a cosmic allure, speckled with starry constellations labeled in Arabic, evoking the timeless wonder of celestial navigation. At the entrance, a tribute to the 12th-century explorer Al-Idrisi sets the tone for the exhibition’s intricate dialogue between past and present. His maps, originally commissioned by the King of Sicily, are reimagined on ceramic tiles through the artist’s interpretation, a process I had witnessed during studio visits.

The video installation’s kitsch aesthetic, featuring vibrant tones of gold, red, and pink interwoven with artificial flowers, constructs a theatrical scene that mirrors the manipulative allure of mass media. Two films vividly evoke nostalgia, blending humor with cultural critique. In one film, Lebanese underground musician Kid Fourteen embodies the 10th-century poet Al-Mutanabbi, a figure resurrected through the writings of Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish. Traversing an artificial desert in a deliberately offbeat choreography, the film humorously yet critically examines themes of displacement, echoing the experiences of those forced to leave their homes after the Nakba.

The video installation critiques the constructed visions of love and perfection embedded in cultural narratives, creating a dynamic tension between spectacle and introspection. Immersing viewers in its entrancing cadence, the video becomes the gravitational force of the exhibition. Its cinematic arrangement commands attention with a compelling rhythm and expressive staging, resonating with the structure of a qasida, known for its monorhyme and rhythmic continuity. The playful staging recalls the visual language of Oriental soap operas and media spectacles, merging vibrant tones and gilded accents to craft a sensory allure. This balance between excess and critique invites viewers to reflect on the seductive power of visual storytelling and its role in shaping the cultural narratives presented within the exhibition. Balancing entertainment with profound commentary, the video anchors the exhibition, urging reflection on what is artificial, exaggerated, and authentic.

Through Qasida: The Impossible Journey from East to West, Liên Hoàng-Xuân channels the legacy of poetic voices like Al-Mutanabbi and Mahmoud Darwish, transforming the gallery into a space of fractured geographies and enduring resistance. Here, memory, personal narrative through love, occidental criticism, and belonging converge in an evocative expression of resilience and reflection. The use of copper, woodcuts, and other tactile materials enriches this narrative, grounding intangible histories in physical forms that resonate with both strength and vulnerability. By interweaving the poetic with the material, the exhibition underscores the power of art to transcend boundaries, evoke shared humanity, and narrate profound stories of displacement, survival, and hope.