The Past Within Us

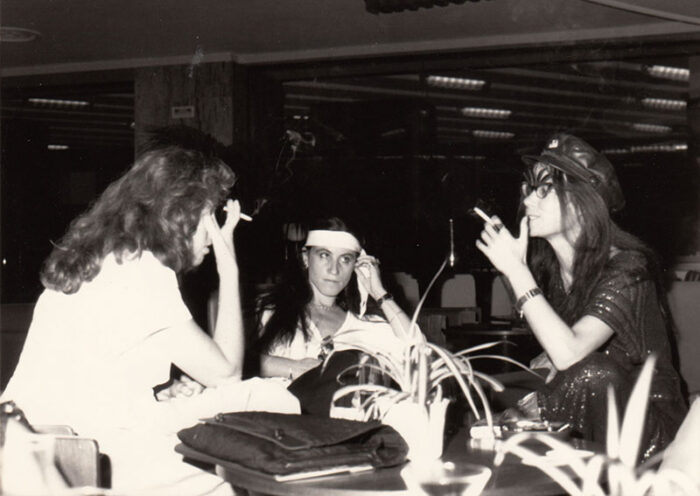

Le Nemesiache and their history of remembering

Curated by Sara Guidi, the project Our Truths Flow Together With the Waves aims at exploring the concept of self-image in relation to landscapes, focusing on the intersection of gender and identity. It draws inspiration from the artistic path of the Nemesiache, a feminist-artistic group based in Naples since the 1970s. With exhibitions, workshops, and a series of texts published here and written by Giulia Damiani, Sonia d’Alto, Mattias Gimigliano and Sara Guidi, the project’s research is centered around the exploration of women condition as a cosmos, explored through various artistic mediums such as dance, music, rituality, and poetry. Our Truths Flow Together With the Waves – Chapter I was hosted at the Italian Cultural Institute in Copenhagen from July to August 2023. Our Truths Flow Together With the Waves – Chapter II opens at Casa Morra – Archivi d’Arte Contemporanea in Naples on October 19th and runs until November 15th.

How to address legacies from the past to work in the realm of a political imagination for the future? How to recast cosmologies based on the institution of a binary system? How to reappropriate forms of knowing, practicing and sensing enclosured by the grid of modern categories? How to recall women and other subjects, canceled and marginalized by the split that separates the cosmos into a scientific object of enquiry? How to introduce an invention into existence (Fanon)? How marginalization and liberation work in alliance in the struggles? From last century, feminisms have offered several proposals for a rewriting of narratives and categories inherited from the hegemonic modernity, and of the fundamental cosmogonic grammar which human history has been invented and transmitted on.

In this regard, it is interesting to refer to what feminist writer and organizer Lola Ulufemi has pointed out: the term “woman” can designate a “strategic coalition, an umbrella under which we gather in order to make political demands. It might be mobilized at the service of those who, given another option, would identify themselves in other ways. In a liberated future, it might not exist at all.” This speculative assumption is grounded in history. Already in the 80s Lina Mangiacapre used the word “transfeminism” to underline how (in her own words) “it isn’t only about the modern man and the modern woman anymore, but about giving rise to a mutating being, whose sexual identity will continually shapeshift.” Androgyny has been the stated basis for an artistic and philosophical approach that introduces “a fluctuating frontier that breaks with given sexual identities (…) androgyny makes use of a force that women have in abundance (…) an androgynous thought is a thought that has its absolute force in the present, but is capable of recreating the past, by reaffirming and reliving the myth, and the future.” [1]

Entwining fabulation and political struggle, myth and making, Lina Mangiacapre initiated the historical feminist group named Le Nemesiache, founded in 1970 in Naples. Simultaneously on several struggles settled in a political reality already engaged with feminism, the group adopted a non-linear methodology based on mythology and rituals, concerned with different layers of meanings and dimensions of feminism. To achieve women’s self-liberation and historical reappropriation, a rewriting of the cosmos was needed, as the myth was coming back into the world: Amazons, Sirens, Sibyls, Prophetess are some of the mythological figures that were invoked and evoked in their collective rituals for trans-temporal communications, radicated in Naples and its cost, then expanded in “planetary boundaries.” [2]

A mythical group among other feminist movements, also the name “Nemesiache” follows a history from the past. Nemesis is the Greek goddess of justice fighting against Hubris, it was chosen by Lina Mangiacapre for her mythological personification, along with other components of the group: Niobe, Nausicaa, Medea, Dafne, Cassandra, Karma, Psiche and many others [3]—women bound by their collective desire to change the world. Yet the mythological names manifest the group’s intention, that is an alternative vision to both feminism and Marxism. In this regard, they always preferred to be referred to as group rather than collective.

The 70s in Italy were shaped by the aftermath of fascism and the Second World War, and many feminist groups sprang out in that period engaged mostly with a revolutionary Marxist mobilization—such as student and worker movements—and socialist instances. Silvia Federici, Maria Rosa Della Costa, Leopoldina Fortunati undertook critical intervention into Marxist theory and practice, by emphasizing the centrality of women’s reproductive labor. In 1972, Maria Rosa Della Costa wrote: “In recent years, especially in the advanced capitalist countries, a number of women’s movements of different orientations and range have been developed, from those which believe the fundamental conflict in society is between men and women to those focusing on the position of women as a specific manifestation of class exploitation.” Le Nemesiache took part in this framework and its political claims, although they inhabited a particular position within the Italian and broader European feminisms of the 70s and 80s. This is particularly evident in their 1976 self-published essay “Salario Alla Casalinga” (Wage to the Houseworker):

“La lotta per il salario alla casalinga non è la lotta di tutte le donne ma solo di quelle donne che si pongono come obbiettivo principale ed immediato un migliore rapporto con l’uomo. infatti per la donna che ha come esigenza principale quella di continuare a migliore il rapporto con l’uomo, sulla base di una analisi dello sfruttamento che subisce in quanto casalinga, la richiesta del salario come casalinga diventa una possibilità di autonomia economica all’interno di un rapporto che non vuole eliminare e diventa nello stesso tempo una possibile soluzione all’alternativa del lavoro fuori casa che in ogni modo non eliminerebbe il lavoro in casa conseguente al rapporto con l’uomo. A questo punto la richiesta del salario viene posta nei suoi giusti termini cioè come problema di una parte delle donne che scelgono come obbiettivo di lotta principale il rapporto con l’uomo, mentre il centro del femminismo, e e non a caso il metodo fondamentale da cui è nato il femminismo in tutto il mondo è l’AUTOCOSCIENZA, è la ricerca dell’idenitità e quindi la ricerca del rapporto della donna con se stessa e con le altre donne, non più in relazione all’uomo ma in relazione a se stessa.”

“The struggle for a housewife’s wage does not belong to all women, but only to those women whose main and immediate goal is a better relationship with men. In fact, for the woman whose main need is to keep improving her relationship with the man, on the basis of the exploitation that she suffers as a housewife, the demand for a housewife’s wage becomes a possibility for financial autonomy within a relationship that she does not want to eliminate, and it becomes at the same time a possible solution to the alternative of working outside the home, which in any case would not eliminate the work in the home consequent to the relationship with the man. At this point, the demand for wages is put in its proper terms i.e., as a problem of some women who choose as their main goal the relationship with men, while the core of feminism, and not coincidentally the fundamental method from which feminism has arisen all over the world is AUTOCOSCIENZA (self-awareness), as the search for identity, thus the search for the woman’s relationship with herself and with other women, no longer in relation to men but in relation to herself.” [4]

In 1970, the same year of Le Nemesiache’s foundation, another feminist group composed of Carla Lonzi, Carla Accardi and Elvira Banotti was born, under the name of Rivolta Femminile [Female Revolt] and centered their practice and actions around the method of autocoscienza [consciousness-raising], to reveal history’s incompleteness via centuries of omissions and exclusion of women. Undoubtedly, Rivolta Femminile represents a significant and decisive moment in the history of Italian feminisms especially in regards to Carla Lonzi, who is considered the founder of Italian Feminism. As much as Le Nemesiache, Lonzi and Rivolta were very critical toward any ideological feminism connected to materialist instances and political movements. Lonzi wrote: “[la donna femminista] afferma che il proletariato è rivoluzionario nei confronti del capitalismo, ma riformista nei confronti del sistema patriarcale” (the feminist woman states that the working class is revolutionary in respect of capitalism, but reformist toward the patriarchal system). Nevertheless, it is exactly Lonzi’s radical writings, practice, and poetics of refusal that will cause her to abandon her job as art critic, and that is often addressed as the cause of the missed encounter between art and feminism in Italy. As Giovanna Zapperi writes, “Indeed, Lonzi considered it illusory to conceive of art as a liberating force for women, insofar as patriarchy had already colonized creativity and culture.” Even if influenced by Lonzi, who Mangiacapre met in Rome in her way back to Naples, the project of Le Nemesiache was based on the assumption that “CREATIVITY IS POLITICS.” [5] For the group, women’s liberation depends on women’s creative self-determination. From performance to activism, film to poetry, costumes to collages, theatre to music, the group embodied both trans-disciplinary experimentation and emotional liberation. Their claim foregrounds emotional liberation through experimenting with multiple forms of expression that challenge gender and categorization, carried out in radical autonomy, outside any patriarchal codes of professionalism. Mostly active in the 70s and 80s, their large activity is comprehensive of five performances, three films, four music concerts, and seven video works.

During those decades they also organized protests and occupations, such as the “Occupazione Simbolica Salvator Rosa” [Symbolic occupation of Salvator Rosa] in 1977, when the group symbolically occupied the abandoned building “Salvator Rosa” with the desire to reappropriate the territory, for “a space for sharing and creation.” Claiming back the dispossession carried out against female bodies and territories, they took action in defense of public space, to guarantee a space for encounters and imagination, offering their political creativity and practices of commonality, anticipating current debates on art and commons, feminism and politics of the commons. Another striking example of their plurality of activities is the major conference they organized called “Una città a dimensione donna” [A city on a woman scale], attended by six hundred women. From the ruins of the earthquake that happened in the 80s in South Italy, they proposed to reverse the economic, political, and social margination that afflicted the area through infrastructural services primarily conceived for women, the most exploited and subjugated subjects there and elsewhere. As they claimed “as much as creativity, the feminist struggle toward sexual rights is combined with the struggle for the right to one’s origins and roots. No more forced migration! Our beauty and art must not be destroyed by our condemnation to survival.” [6]

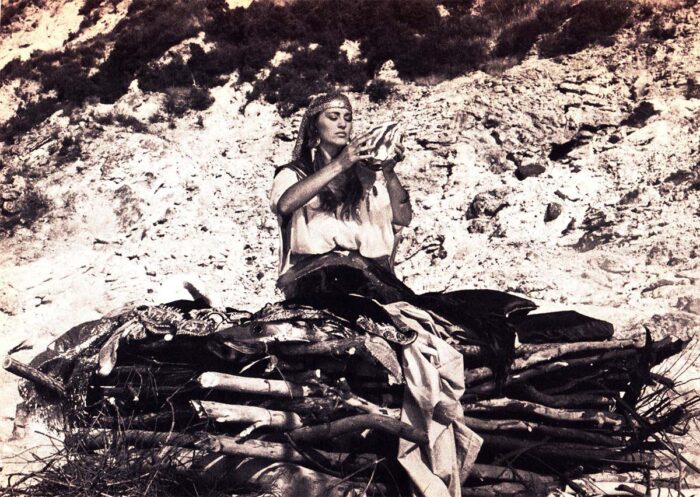

Whilst Rivolta Femminile adopted the consciousness-raising method based predominantly on words, so to unhinge female subjectivity within the patriarchal “cultural discourse”, Le Nemesiache introduced the psico-favola (psycho-fable), a form of psycho-emotional liberation of the feminine that integrated rituality to the verbal language they used to rewrite folktales and myths. Gestures belonging to prayers, places of worship, and ancient beliefs were used as means of expression and communication to trigger self-determination and collective liberation, to create the possibility of the emergence of a political subjectivity. If Carla Lonzi’s feminism “imagined an autonomy that seems to be possible only at the level of the interior self”, with Le Nemesiache and their bodily approach, their poetics of the flesh worked as a proposition for another cosmology. In their multiple practice, myth, body, and rituals intersect as devices to rewrite the cosmos. Refusing the distinction between creative and productive moments, they overturned the scientific authority, redressing the very foundation of Western thought that relies on a model of the universal Subject and the binary opposition of nature and culture. More than any feminist struggle, they carried out a “metaphysics of the struggle.” Gender issues were intersected with ecological, social justices, work, housing, and health matters, as the struggle was inscribed in the embodiment of a different ordering based on “creativity, politics, erotism, toward a new harmony with the cosmos.” [7] Their metaphysics and praxis of struggle uses art as a political tool, continually addressing the harmful binary opposition between theory and practice, while pointing at a regime of oppression distributed on multiple layers: “the essentialist utopia of nature, the organization of (productive and reproductive) labor , and the male privilege of creativity.” [8] Indeed, it is difficult to capture the group’s dynamism without objectifying or disenchanting it, as it was animated by a continuous process of re-creation through ritualistic practices, memory and planetary ancestral remembrance of the everyday enchantment, relegated by the patriarchal secular logic to the oneiric dimension. In this way, they transcended any institutional formation, embedding themselves in the materiality of life, where the pursuit for beauty coexist with the one for social justice, where political commitment and fabulation can co-occur, repossessing a sacred wholeness erased by secular powers. As stated also in their manifesto: “We shall invent and create our struggle, as we will with our sexuality and our culture”, addressing “a new dimension or, let’s say, a new metaphysics that can turn everything upside down, as our creativity is our emerging world that explodes as it turns upside down and reveals infinite fantastic unpredictable dimensions.” This expresses both the painful and joyful awareness that the cosmos can and must be re-written, re-imagined, and once again generated in a dream, in poetry, in the depths of what has been neglected by body and memory’s resonances, to overcome all those colonization processes internalized by women. In Naples and Milan in 1972, and in Amalfi later in 1975, Le Nemesiache performed Cenerella, the first Italian feminist play created by the group from a reworking of the Cinderella story based on the medieval Neapolitan version, using their method of psycho-fable. The rewriting of the folktale allows the protagonist to break free from the female canonic role. With the psycho-fable, Nemesis comes back, making the transformation “from pain to consciousness, to denunciation, to revolt” [9], opening a space for the invocation of a set of bodily revelations and historic reappropriations.

“La psicofavola – fantasia al femminile – il teatro: teatro come libera esplosione dell’energia vitale, liberazione che può avvenire attraverso la fantasia, che, unica realtà non completamente razionalizzata, può ancora dare la chiave per scoprire se stesse e le altre”

”The psycho-fable—a female fantasy—theatre: theatre as a free explosion of vital energy, liberation that can come through fantasy, which as the only not completely rationalized reality can still give a clue to discovering oneself and others.” [10]

What is proposed is a relation between women, between self and “the other than self”, in a cyclical circular search for a common space to co-create a bodily writing. Their 1973 Manifesto Metaspaziale claims: “Beyond the boundaries of the space in which one lives (…) arises the desire to trace and connect women that are close to each other, meaning women who have placed themselves critically beyond cultural barriers, and can also be affected by situations that take place in a distant physical space.” Seemingly anchoring and transcending the space at once, what postcolonial theorist Gayatry G. Spivak defined as “planetary ethics” emerges : the possibility to think the impossible from the borders of the cosmos, to reimagine common relations, tracing and retracing alternative politics to the patriarchal and colonial systems of powers, and overcome the limits of binary thinking (as they did) from the margins of Europe.

The performance Cenerella was later transposed on film (1977), where the group manifest, through performative gestures, critical fabulation, material experimentations, a ritual that unfolds simultaneously what has been lost and could still be recovered. The ritual becomes an instrument of redress, a potential memory-technique, and an imaginative invocation to re-appropriate history, thanks to the use of the myth. By wondering “why do we move from the mythical to the conceptual form? (…) what do you want to forget forever through the conceptual logical form?”—Mangiacapre recognized how, in its abstractness, even logic could be a threat to women’s liberation. For the group at large, women liberation depends on their creative self-determination. Mangiacapre was searching for alternative methods of communicating in a way that preceded the concept, as she thought that this precedent was to be found in the myth: a pre-logos dimension, to become attentive to desires and to have the present repossessed by the past. In this regards, mythology was adopted by the group as a speculative feminist strategy, to overcome the trap of male-centred logos, to rewrite time and space—in their own words: the most oppressive, colonial and patriarchal of all settings—in order to assume a different relation to the world, based on a strong interconnection among all forms of beings, by rewriting relegated and repressed subjects and narratives. The use of the myth intersected with political resistance, conjuring the archaicness of the past with the urgency of a possible future.

“Myth used to be this form where the body was” [11]—an embodied knowledge of alternative materiality and subjectivity. This new mythology and its ritualistic specificities worked as an excavation of a deep forgetting, the search for a cyclic common space, centering women’s self-determination and self-liberation strategies within the forgotten (female) emotive dimension by considering that “so much of how we remember is embodied.” Techniques for exploring the self and the external world through the incantatory power of ritual repetition, mythology, ancestral symbols, geological and archaeological materiality were embodied to unfold the self produced by a contemporary identity, and to reconnect with a cosmic language and metaphysics through multifaceted and circular timelines. In an invocation of memory and beyond an evocation of gestures, in their collective rituals and their creative moments together, as well as in their film, they expressed a co-belonging with the sea, the rocks, the volcano, and its lava: rocks and land hold memories, as waters always remember. Aware that “the sacred is inconceivable without an aesthetic” the group used creativity as a feminist practice of re-appropriation, for recalling and reversing present and past imaginaries, and finding other enchanted dimensions suppressed by the hegemonic culture.

The praxis and formulation of Le Nemesiache’s struggle doesn’t consist simply in claiming to be a feminist group, but first and foremost in being a political reality that reconnects itself to Naples and to Cuma, the female oracle of the Sybil, in order to remake another knowledge, a different future that is historically charted by the past only poetry can give an approximation of. Cuma becomes the ancient portal preserving the ancestors’ memories, the channel for knowledge transmission, and an aesthetic dimension. Thanks to this mythology, the links between past and future intertwine, knotting together two reputedly disjunct threads, namely spirituality and politics. Le Nemesiache elaborated a radical creative response to that secularized, rationalist and disenchanted project which, through history and patriarchal culture, relegates spirituality to an illusory, manipulative or populist status. In this way, not only myth was juxtaposed to a secular scientific rationality, but also used to redraft a whole cosmology, using the liminal reflexive means of bodily knowledge and its interconnection with the surroundings. As Mangiacapre wrote, cinema itself “is our autocoscienza (self-consciousness-raising method)” [12] a way to re-appropriate history and to experiment solidarity with other women:

“Il cinema potrebbe essere un importante strumento per l’appropriazione di una dimensione storica. Ma prima di procedere bisogna, oltre alla riscoperta delle pioniere, donne lontane nel tempo e nello spazio, ricordare e amare quelle presenti vicine, non ignorare la nostra storia contemporanea, le lotte che hanno portato in primo piano la presenza delle donne nel cinema, la nostra breve e folle lotta per un mondo che ha sempre tentato di escluderci.”

“Cinema could be an important tool for the appropriation of a historical dimension. But before proceeding, other than the rediscovery of the pioneers, women far away in time and space, we must remember and love those who are present and near, instead of ignoring our contemporary history, the struggles that brought women to the fore in cinema, our brief and maddening struggle for a world that has always tried to exclude us.”

Le Nemesiache’s cinema was conceived as a sort of proto-cinema, as they refused any role and professionalism inherent to mainstream cinematography industry, by setting moving images free from a patriarchal scale of values. They were producing their own soundtrack (psico-musica), their costumes (psico-costumi), their lights (psico-luci). To reverse space and time, in the potentiality of a new film-making language, they glimpsed the possibility of a “recomposition of the tremendous and rigid Kantian categories in cinema.” In this light, with the political purpose to keep the memory of the feminine at the heart of their action by talking about women and by presenting their work, they founded a feminist film festival “Rassegna del Cinema Femminista in Sorrento” that ran between 1976 and 1994 along the Neapolitan coast. They invited women from all over the world to accomplish an historic re-appropriation and express the many possibilities of feminist film-making. Feminist cinema became a technology for them to restore memory, to access a certain creativity not only based on dyadic principles, but on women’s cyclical rhythm. Their invocation to “return to the womb of the earth” lies in recognizing how “the pitfalls are in linear time, in the history that oppose nature to culture” and the need to expand it “toward a deep time.” [13] The centrality of the body and rituals opens up a temporality and a spatialization very different from the categories of modernity. The surrounding landscape came to be seen as holding the key toward a collective consciousness buried deep underground in the geomorphic environment, in the archeological ruins, and in a mourning that women conjured in rituals aimed by a mnemonic invocation: “there is still a trace of these roots, in ourselves, in the archaeological ruins, in the magic of revisited places, in the subculture of a certain prediction that still exists in the old women of Naples; this journey is possible.”

Memory becomes a technique of imagination, and history a metamorphic process interconnected with the surrounding landscape where, these new Amazons struggle in—“warrior places of the present, of myth, of history, of fabulation” [14]—as the world begins again in “a cosmic dimension as another dimension of the feminine.” This new dimension follows a cyclical nature that belongs to the magical world—to the transformative power that characterizes this very cyclical nature. Magic has often been a bearer ostracized by capitalism, as philosopher and activist Silvia Federici explains in her seminal analysis of the witch hunt that accompanies and drives capitalism’s process of “primitive accumulation.” As pointed out by Federici the enforced split between nature and the cosmos was first generated by the enclosures of women’s bodies, followed by land enclosure—not the other way around. The effect of these enclosures was the construction of a capitalist work discipline that erased a conception of the cosmos that was otherwise full of magic and cooperation. In regards to mythology, Mangiacapre had similar considerations, historically placed in a mythical past, describing how the Amazon were killed by the Greeks, who invented the concept to disclose the enchanted dimensions of women and the cosmos. For these reasons, the myth needed not only to be re-written but also collectively performed, through gestures and experiences usually marginalized by the patriarchal law. For Le Nemesiache every gesture is “a historical fact”—as the gesture is nothing but an unspoken word, something left either repressed or unarticulated in the mastery of the hegemonic language, but richly deployed in rituals and magic conjurations.

The magic eradicated by women’s bodies toward a rationalization of the world invests all phases of the human life cycle, from birth to death. During the 50s and 40s, ethnographer and philosopher Ernesto De Martino had thoroughly studied that world of magic in the South of Italy, and applied it to the materiality of the rural world, which was also drawn on a circular conception of a life based on rituals, against any vision of a southern supernaturalism. In the magical rituals of the South of Italy De Martino envisioned a cosmology of a subaltern world, in the very same territory where Le Nemesiache anchored their practice, working against the folklorization of the territory, there they found traces of different humanity, a conduit of feelings and fantasies connecting all the elements of the natural world into a cosmic city. Their approach to the geological, archeological, and mythological places of the South—Naples and the Phlegrean area in particular—is vernacular, playing in the liminality between high and low culture, instilling a call to witness the fine line between progressive and regressive, normative and challenge, and a response to be more than an abstract body. In their refusal to be part of an art world and a knowledge system constructed and based on a patriarchal grammar setting, Le Nemesiache’s autonomy finds the key to liberation in old rituals and in cosmic cycles, a chance to self-institute another metaphysics of life. Thus, they fabulated around ecological, hospitable and transformative dimensions to shape a vital and interdependent planetary relational architecture embracing cosmic and poetic alliances:

“Scoprire l’unità dei secoli delle nostre lotte è stato ed è riprendere il ciclo cosmico di tutti i mari dei soli e delle lune attraverso le maree di sangue, le lave dei vulcani, i roghi di tutte le streghe, riprendere me stessa e tutti i miei rapporti, costruire la storia di sempre, la storia come vita, come armonia”.

“To discover the unity of our struggles throughout the centuries meant and means to take up the cosmic cycle of all the seas, of suns and moons through the tides of blood, the lavas of volcanoes, the burning of all witches, to take up myself and all my relationships, to build the history of all time, history as life, as harmony.”

This was a proposal to change the space of interventions and experiences, to reimagine other ways of transmitting and sharing resources both material and immaterial—a mutual exchange to make a space of resistance and a site for connection. By fracturing the modern temporality, Le Nemesiache recomposed the boundaries determining self and other, inside and outside, here and elsewhere, fracturing the colonial spatiality in a way they embodied epistemic breaks and paradigmatic changes towards a cosmic solidarity, in a creative geography:

“Desideriamo una presenza critica delle donne che valutano al positivo una lotta per rompere ogni forma di emarginazione del Sud. Intendiamo per Sud tutte le forme di energia che vengono sfruttate in vari modi non valutabili in termini economici, senza che si consideri tutto questo come sfruttamento.”

“We wish for a critical presence of women who have a positive approach to the struggle to eliminate all forms of marginalization in the south. We take the term ‘South’ to refer to all forms of energy that are exploited in various ways that cannot be assessed in economic terms, when all of this is not considered as exploitation.” [15]

The experience of Le Nemesiache look back at both the material and the emotional life to remember what has been dispossessed. In order to invoke a collective future where to instill confabulating solidarities with other temporalities and subjectivities, other than those inherited by the patriarchal and colonial modernity. In the act of remembering, Le Nemesiache found the path to desire, to resist, and to survive: “Together we shall rediscover the hidden, violated, trodden path: our burnt path.” [16] As particularly expressed in their film “Le Sibille” [The Sibyls] (1978) and infused in Le Nemesiache’s overall political-poetic practice, remembering the future in the past within us is coalescing together the embodied will of a whole movement towards freedom.

[1] A. Putino e Lina Mangiacapre, “Il Mito della donna guerriera”, in Manifesta n. 0, 1988, 1–3.

[2] Le Nemesiache, Manifesto Metaspaziale, 1973.

[3] The group has been animated by up to twelve women, whilst the core of the group consisted of at least five people Lina Mangiacapre, Teresa Mangiacapra, Fausta Base, Silvana Campese, Conni Capobianco among them.

[4] Le Nemesiache, Salario Alla Casalinga, 1976.

[5] Le Nemesiache, Manifesto per la riappropriazione della nostra creatività,1977.

[6] Le Nemesiache, Per una città a dimensione donna, in “Quotidiano Donna”, 1981.

[7] Le Nemesiache, Manifesto per la riappriopriazione della nostra creatività, 1977.

[8] Giada Cipollone, “Nemesi Performativa. Scritture Corpi e Immagini nella ricerca di Lina Mangiacapre e delle Nemesiache” in Mimesis Journal, 10, n. 2, Torino 2021, 41.

[9] Lina Mangiacapre, Cinema al femminile, Mastrogiacomo Images 70, 1980, 2.

[10] Le Nemesiache, Cicli solari [Solar Cycles], 1975.

[11] Lina Mangiacapre.

[12] Lina Mangiacapre, Cinema al femminile, p. 7.

[13] Lina Mangiacapre, Opera Totale, 1976.

[14] Angela Putino, “Cosmo,” Via Dogana (Milano: Libreria delle donne, 1987), 37–40.

[15] Le Nemesiache, Nemesi il cinema, Napoli, 30 agosto 1976, in Effe, Bari; Roma, aprile 1977

[16] Manifesto delle femministe napoletane: Le Nemesiache, 1970