The Museum’s Subconscious

A polyvocal conversation from the workshop “A Collection in Turmoil – Practices of Autocoscienza” led by Adelita Husni Bey

On September 19th and 20th, 2023, If Body presented A Collection in Turmoil – Practices of “Autocoscienza”: a workshop led by artist Adelita Husni Bey in the spaces of the Museum of Civilizations.

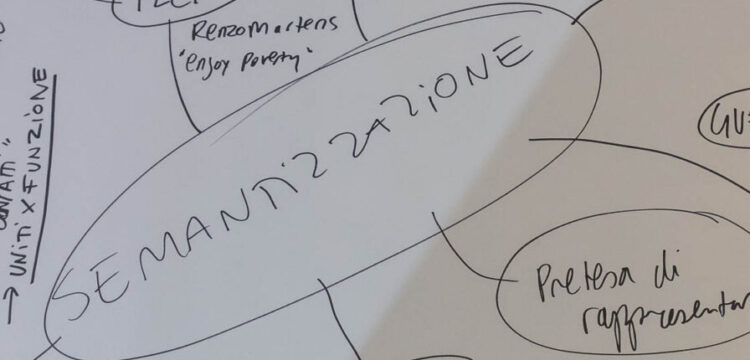

This workshop marks the second instalment of a project launched in 2022 as part of the Hidden Histories program curated by LOCALES. On this occasion, the “body” of the museum was approached through the lens and dialogical practice of “autocoscienza” [consciousness raising] to inquire whether the institutional “subconscious” could be accessed in some form. Referencing the work of Carla Lonzi and the group Rivolta Femminile—revisited from a transfeminist perspective,—the workshop delved into questioning the role of art institutions, through writing and theatre exercises.

The following text is the result of the partial transcript of a polyvocal conversation that took place in the Museum of Civilizations on the occasion of the two-day workshop. The participants discussed topics such as the power dynamics affecting art institutions, the non-neutrality of display methods, the publics addressed by museum policies.

If Body is a public visual and performing arts program that focuses on the body as an artistic language and learning methodology based on experience and participation. Conceived and curated by Sara Alberani and Marta Federici (LOCALES), it presents new performances, talks, workshops and exhibitions that explore the cultural, social and political meanings associated with the body and corporeality through six events. The first edition involved interventions by Amelie Aranguren (INLAND – Campo Adentro), Marie Moïse e Mackda Ghebremariam Tesfau’, Pauline Curnier Jardin & Feel Good Cooperative, Adelita Husni Bey and Holly Graham.

Conceived by Chiara Pagano with the artists of the If Body 2023 program, a series of editorial features delve into each specific event and happening.

Yesterday we tried to answer these questions: what does “autocoscienza” mean? What is its history? How does one practice it, in methodological terms?

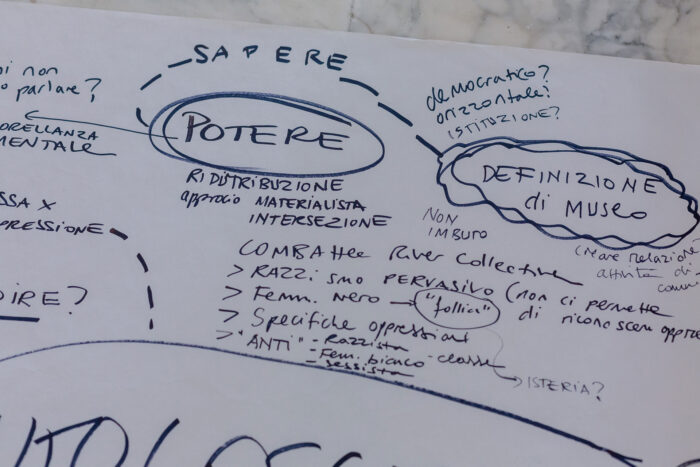

Some of the things we said are: “it is a tool to understand one’s power, power structures, auto-narration, and collective narratives;” to “recognize and identify”; “to decolonize someone/something from a colonizing hegemonic system.” It is not an “engine” of action but a process that postpones action in order to move towards a mass movement against oppression. It is an instrumental tactic of listening, of sisterhood. We also talked about intersectional modalities, and starting from the Combahee River Collective text we even reflected on its limits.

What came to mind as I read your definitions?

When we gathered today, we summarized what emerged yesterday, the fact that self-awareness as a practice can take many forms, but that at its core, there is a willingness, a commitment to bring this process to bear.

True. In the Combahee River Collective text, privilege as a component of the possibility of conducting practices of self-awareness emerged: being able to afford it; it seems as though they were experiencing such a high level of urgency that consciousness-raising appeared to be too slow…this is what emerges for me from this particular reading, perhaps it’s a practice that requires a certain timeframe.

At the methodological level, it’s a practice that requires a lot of time.

Consistency.

Yes, but then they go on, and say, for example, that “as lesbian and black feminists we know that we have a definite revolutionary duty to carry out, and we are ready to face the life of work and struggle that lies ahead.” Well, for me, self-awareness is a revolutionary duty. We also have a group. We meet twice a month; when I cannot attend it, I feel I’m not doing my duty; I recognize myself in this revolutionary commitment. But yes, I also acknowledge that it could be a slow process and that not everyone can afford it; it is not suited to all situations and contexts.

According to this methodology, If we want to apply this practice to an institution like this museum, we can affirm that it needs consistency, a proper amount of time, and perhaps, similarly to the 150 hours [1] school, it needs to be offered by the institution with paid time off work…these parameters would be ideal for this process to be realizable in some way.

Our group reflected on the relationship between the museum and the collection as a point of departure…well, of course, the object is not isolated…it is always narrated by someone, by the institution.

Yes, on this note, I liked the parallelism we made—of the museum as a body—which makes me wonder what its voice is, because, in my opinion, we didn’t talk about it enough yesterday, while this question is central.

I like the association you made, however, I also want to raise another kind of association that came to my mind. Starting from the assumption that self-consciousness was born to question the patriarchal system, what if it were the museum—and perhaps that which is outside the museum—that spoke through a patriarchal voice? What if this patriarch were the ministry? I mean, the voice of the museum, which is it? What are the rules that the museum has to follow? Where do they come from? From within or from outside?

Right…we did state that public museums depend on political power, the ministry’s political power.

Well, perhaps, it is the political power of the ministry that represents oppression. What is the subjectivity of the museum? How much freedom of action does it have? Then, using this provocation of the body…we may also have to pay attention to how the individual entities or parts operate. One of the staff members gave us their self-narration of the museum, and it may or may not coincide with the self-narration of other staff members.

For example, I loved what emerged from yesterday’s narration of the museum as a body, and I agreed with it, but while the museum was described as a multi-headed hydra, I imagined it more as a filiation, a physical propagation attached to the ministry which gives it directives, funding, and support…it is as if there were a giant umbilical cord attached to it.

This is also because there are sponsors.

That’s right.

Sometimes the board counts infinitely, however, community members can also be part of the decision-making process bringing different questions and perspectives. That’s precisely how it is legally structured.

That is, we have to keep in mind power relations.

They come from the above but they can also come from below: requests emerging from the community or society, from public debate…let’s say that museums are at the intersection of multiple dynamics: positive, negative, whatever they are.

When the institutional voice emerges, it can be more or less defined, and this depends on whether there is a well-controlled communicative flow that allows the museum to speak with a single voice, with a single tone, with a single modality, in accordance with the message. It’s a job, the museum has to work on it, uniting multiple voices to have a unified voice.

Then there is the question of heritage management, understood in terms of the collection itself and the management of public funds.

I’m not sure if we are aware of it, but we are currently practicing “autocoscienza”.

It is helpful. I am discovering that what I have always referred to as “practicing political anthropology” is actually practicing self-awareness.

It requires vulnerability and, sometimes, looking closely at concrete conflicts that have occurred, and that keep occurring.

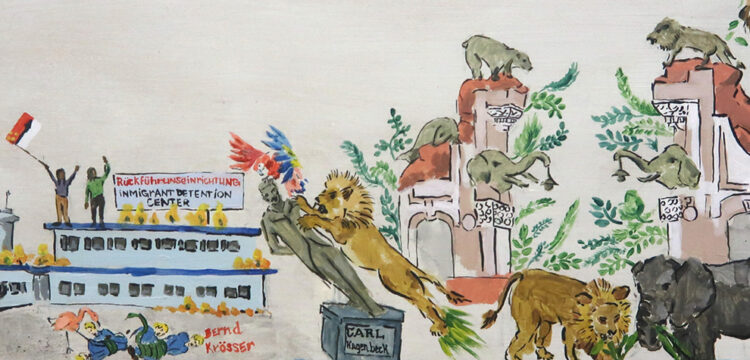

I want to raise also questions like: what kind of collections does this museum have? What is stored in its belly? Because it is very different from other kinds of museums. We are discussing its subconscious, what has been repressed, we discussed reparation, and restitution, in short, many topics that we have been addressing over the years…perhaps if there were a consciousness-raising group within the museum, I feel, as a museum visitor, that all of these topics could be its starting point. What do you do with violent objects? Because this particular museum has them. What do you do with misappropriated objects?

Last year we were dealing with decolonial processes, this year we are talking about the practice of consciousness-raising…well, how do you practice it? This museum is profoundly wounded. Then I also wonder: the staff who are participating today, how do they deal with this wound? How much does it hurt to work here? What does it entail? How do they deal with processes that may be considered neutral or cold—like preservation, protection, and cataloguing—versus processes that can be seen as emotional, linked to consciousness-raising practices? These are probably important matters to address…

Absolutely. And then what is repressed in self-narration, right? I mean, in the task of self-narration, everyone ends up leaving some things out, and what you leave out is often the core, what we didn’t remember, what we didn’t include. So, I think it is fundamental to go back to these self-narrations, as that is where that which is repressed in the museum is to be found.

There’s something interesting thinking about the many questions you’ve raised about how to practice self-awareness…we’ve been repeating that one of the main activities when practicing self-awareness is to do it in relation to things—objects/subjects– that are similar. Well, I wonder how this collection looks at other collections? How could it be in dialogue with a collection that is in Africa, Oceania, South America? How could it create an exchange with a collection in another museum?

What I am suggesting perhaps, is the possibility of practicing self-awareness among various museums that are tackling similar questions around the world. Because the issues we’re touching on here are also being addressed in other places.

Yesterday we cited the ICOM definition [2] to ask ourselves what a museum should be; this is a long-standing discussion in Europe as well. Perhaps we wouldn’t have come up with such a broad, progressive, innovative definition without the transnational conversations we had, especially since countries that were subjected to colonialism have begun reflecting on these questions far before us—how museums should deal with a given historical period or something erased from history.

The last time I visited an exhibition at the museum I came with an Afro-Italian friend who complained: “Before seeing this, I would need a disclaimer because it’s violent…”

Seeing these objects, which are connected to real violent acts, obviously made me feel angry, but for him…the way a work is exhibited can be disturbing. This is to say that, in addition to all we spoke about, there’s the need to understand how to display certain works, especially considering that Italian schools do not tackle these issues. The effect is that this 40-year-old peer of mine couldn’t fully experience the museum, because the experience was mostly disturbing to him. He then also pointed out to me how the audience that day was mostly composed of white people. He said, “Maybe it’s because—knowing that this country is still so behind in confronting its colonial past—for us as black people, entering this building is exhausting. To be confronted for a few hours with these objects is just trying.”

I wanted to highlight how, when we came back from visiting the museum’s collections, and we took a moment to breathe together, it was very important for me, because I felt a certain darkness in there.

Because the museum is public property, and we’re in the public sphere, it’s everybody’s and everyone’s business. It’s not an impartial institution, and this is because when we evoke the institution, we always associate the institution with neutrality, something that is managed at a State level, which offers it a certain kind of legitimacy. Well, this is false. Deconstructing this very public issue is important because people still go to museums convinced that everything they see is impartial. Except for those who are directly affected.

In its posturing as impartial, it revokes its own responsibility.

In my opinion, neutrality never exists. Primarily as the object itself is never impartial.

Those who have the power of speech share a responsibility…in a public institution, more often than not, it is the curator—or whoever has, I like to say “moral duty” rather than just “authority” (these are two very different concepts)—who has the responsibility to give voice or voices, which is in itself is a choice: whether to use the singular or plural. It’s a huge responsibility, and precisely this choice…is it just theirs to make or not?

The problem here is whether or not to make one’s perspective explicit. I mean, an exhibition always implies choices.

The problem is that what reaches the public is perceived as true, an unquestionable reality. The challenge is to express that what a museum offers is only one of multiple authorial points of view, while also specifying who the author is. Usually, colophons are that element that you include at the end, with the names written out in small font, but it seems necessary to me for a museum—even a public one—to make its perspective clear: whether someone wrote something, who wrote it… stating that there is both a motivation and a position. This is a type of institutional self-reflexivity, an institution reflecting on itself, making an effort to position itself and say, “I made these decisions because I want to reach these goals.” And trying to convey to the audience that what they are looking at is not the ultimate truth, but a possible path, a solution, a proposal…

While also being aware of the power that you have, and therefore yes, of your responsibility. At the end of the day, the museum is like a written text, often taken to represent the absolute truth, while we have to question the very concept of “absolute truth”.

It is difficult, as an exhibition-goer, to visit a museum and not have that approach.

It is like that exercise we did, following our partner’s hand. [3] The desire to be guided while asking questions at the same time. Why is this hand guiding me?

One last thing I’d like to talk about is the processing of one’s pain, which is something that has emerged from the visitor’s remarks, and which is an important component of consciousness-raising. The recognition of oppression, even within the museum, can only be achieved when there is a recognition of pain. So I wonder how one could deploy a clear, vulnerable approach that allows one to temporarily relieve oneself of one position as an employee.

In my opinion, going back to the text of our group, the basis of the museum—and more generally in life—is respect and empathy.

It’s a beautiful conversation, let’s continue it while we have something to eat.

[1] In 1973 the 150 ore law was introduced in Italy. It allowed all female workers to study through a free 150-hour course, paid by their company.

[2] In the framework of the 26th ICOM (International Council of Museums) General Conference held in Prague, the ICOM Extraordinary General Assembly approved a new museum definition: “A museum is a not-for-profit, permanent institution in the service of society that researches, collects, conserves, interprets and exhibits tangible and intangible heritage. Open to the public, accessible and inclusive, museums foster diversity and sustainability. They operate and communicate ethically, professionally and with the participation of communities, offering varied experiences for education, enjoyment, reflection and knowledge sharing.”

[3] During the two-day workshop Adelita Husni Bey invited the participants to perform an exercise called “Columbian Hypnosis” in couples: one person places their hand a few inches from the face of another. The latter, as if hypnotized, must keep their face always at the same distance from the hand, while following the hypnotizer movements.