The Library of the Air

Staying with the trouble in the critters’ room

The Critters Room is a project conceived and realized throughout 2020–2021 by the collective Jan Voxel, and further developed during their residency—Artists in ResidenSì—at Atelier Sì, in Bologna. The multimedia interactive installation unfolds around the visual and practical information carried by the fine dust and particulates, and their inextricable relationship with the human species.

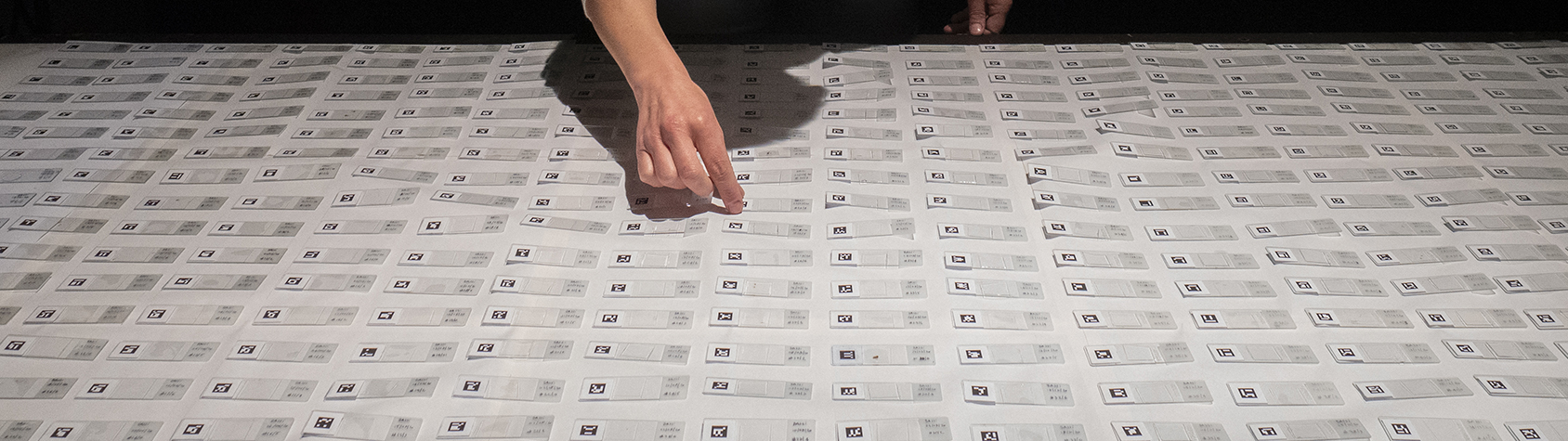

Everyday since March 2020, a laboratory slide was placed in the open air to collect its particulates, and stored as a trace of the daily status of the atmosphere. Viewed through a microlens the fine dust appears as an ever changing landscape that depicts and testifies the interaction and correlation of different species and geological eras. The final installation allows the viewer to browse and learn through four different archives, and bear witness to a specific moment in time, through a layered set of information.

During the building of the archive, which was slowly shaped as some sort of library of the air, NERO had the pleasure to follow the process along, and here a trace of the conversation we kept in the past months.

Let’s start from the critters: you use this word drawing inspiration from Donna Haraway latest work, in which she choose to use this word—an American informal word to define “varmints of all sorts”—as a way to overcome the distinctions between human and other-than-human living beings of the Earth, in order to foster a multispecies thinking and perspective. In your work you use the word critter to generally include what you call the inhabitants of the air, which for the most part are now particulates, including both organic and inorganic matter, and especially by-products of hydrocarbon combustion. You see these particulates as “ghosts” of the soil organic matter that lived millions of years ago, before decomposing and transforming into fossil fuel. How do you conceive the idea of a possible sympoiesis with these ghostly critters?

It’s true that the first and foremost way we use the word “critters” is by referring to what we measure with the particulate sensors, and what we see on our collection of microscope slides. But actually, “the room” is filled with a whole larger spectrum of critters: the molded trilobites, us, the machines (software, hardware and the data they contain), the voices and sounds, and last but not least the people who come experiencing it. When we think of a possible sympoiesis, we do think of a “making-with” all those elements.

That said, we think that the critters of the air, with their “ghostly ontology” you so rightly emphasized, are the key to a “multi-timescale” thinking and perspective, to stick to your expression. As Morton says, an object like “climate change” is an hyperobject, elusive both from a conventional space and time scale. So, those ghostly critters help us to come to terms with the necessity of a perspective which is to be multispecies but also with a totally different sense of the temporality and the permanence, freed from the “hunter’s straight arrow” narrative, to use a Le Guin metaphor. Those visions are all about coexistence. This element, in our vision, is another key element for really “making kin” to what already exists, existed, or will exist.

The critters’ archive is meant to be nomadic and adaptable to different places and contests. How do you usually interact with the local community and what is the procedure during the collection process?

Initially, there’s usually a spread-the-word procedure, by which we try to get in touch with as many actors as possible, from local communities which have chosen to “stay with the trouble” through their practices, namely environmental activists, politically-aware artists, grassroot movements, just to name a few. We usually meet and talk to them, collect their voices—“what is your local problem you are staying with? How? Whom do you share it with?”—Then, we ask them, if they like, to become local performers on our behalf, to keep the microscope slides exposed to the local air, so to number and collect them. We also provide a “Critters kit” and a very handy “how-to” guide. Everything then merges in the same archive. Some also decide to engage in the data collecting practice, by installing the self-built particulate matter sensors to collect open data about air quality in their own spaces (from private houses to social centers).

In your work, a key concept is memory, memory of the air, which on the one hand is the memory stored in the air, i.e. for the fact that everything we find in the air we breathe today is a residuate of living matter and beings that died in previous geological eras; and on the other hand, one of the goals of your actual work for The Critters Room project, in which you collected “air samples” to form a chronological archive of what’s in the air of a particular place, to build a memory for the future…

Definitely, memory is one of the key elements. With the (maybe obvious) assumption that we do not mean either static or consolatory memory. In this sense, it’s totally true that The Critters Room is a “bidimensional memory tool”—as it concerns memory on every slide, layer upon layer, dust upon dust, then-living upon now-living, in an amazing short-circuit revealed by the micro-photography

(in an ephemeral way); and memory shapes into an ever-growing archive, a memory of—maybe—some use in staying with the trouble. Memories of present-present, present-past, present-future, past-future-connectedness.

The installation is composed of different chapters/elements/sections. How have you structured it?

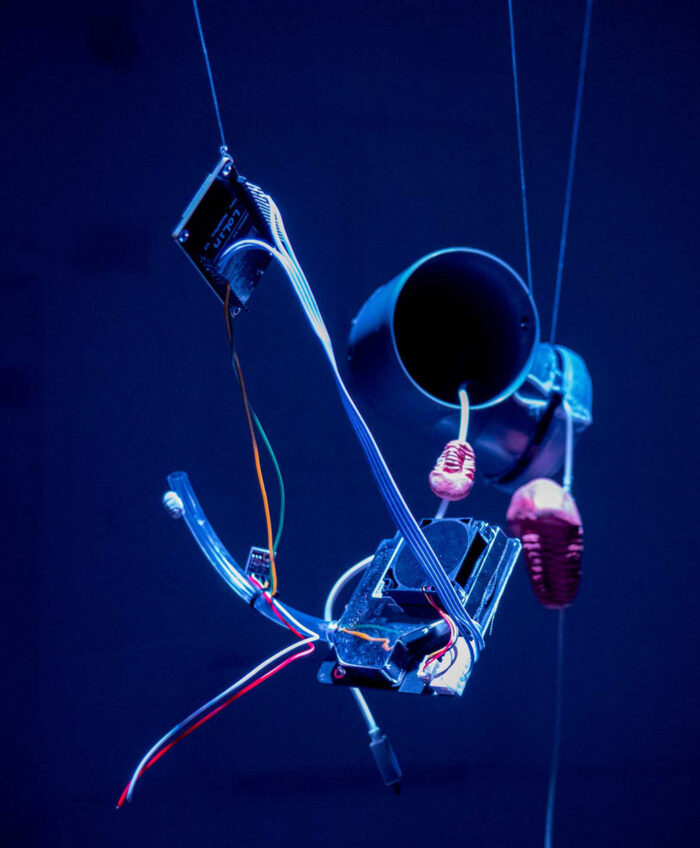

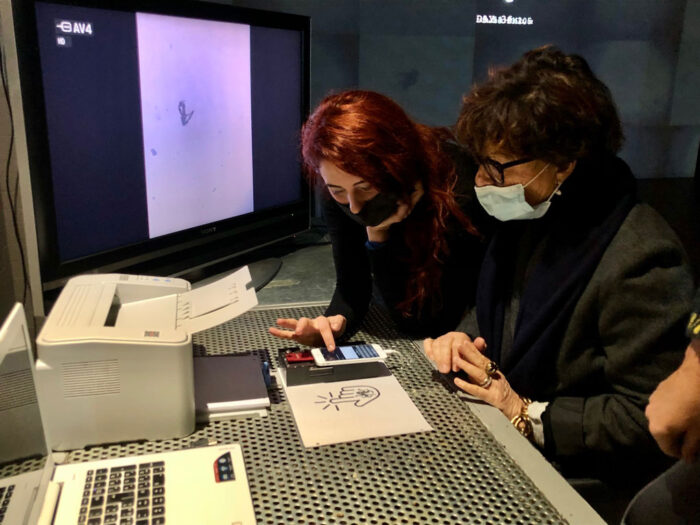

The Critters Room is partly a route, where the viewer can travel by itself, and partly an open lab, where people can be guided in the process of taking micro-pictures of a chosen slide, then generate their own critters images, and from the slide access the audio-video digital installation composed by daily collected PM data, collected sound, collected voices. The viewer is welcomed by a more or less conventional sculpture, where the oil-trilobites and the exploded sensor are all entangled, in some sort of a “welcome to a world of connectedness” message, given out by a very traditional media.

Then, the room unfolds. The ever-growing slide archive exposed on a table, the patterned pictures of the places where we collected the data, the critters images projected on a semi-transparent tulle screen, the audio-video installation, the picture lab. The viewer can freely travel through this path, and/or be guided by us into a custom experience, which we could define as a journey into different archives, different views of the same hyperobject we’re dealing with. A journey that ends with a “bibliography archive”, a freely browsing big case full of many of the books that have been our guide, inspiration and nourishment during the preparation of the work.

The visual archive you built during your residency in Ateliersi is a strange object, some of the images produced by the magnification of the glasses are so fascinating that the viewer could be seduced by their aesthetic appeal, or rather be scared by the idea that what they see is what they breathe. What have been the reactions of the people who interacted with your project during the residency and how they helped to shape the final work?

Both ends of the reaction spectrum were definitely present, from aesthetic seduction to a feeling of doom, together with many intermediate shades in between. Let’s say we’re at ease with the whole spectrum, each reaction being a totally effective way to get in touch and to make kin. In this sense, not to dismiss any reaction is the first lesson we learned. We then tried to balance and fine tune the levels between the viewer’s personal discovery and guided experiences, to provide a non-narrative, multi-language and stratified set of tools (both written and oral, a sort of “weakly-interacting guided tour”).

We also discovered that the images of the critters can suggest very rich imaginaries, far beyond their concrete presence referring to pollution. From this observation, a collection of fantastic stories about the critters was born, which we are collecting to create a series of podcasts entitled “Olga legge i critters” (Olga reads critters).

To point out a final remark, we learned that the critter’s images, and the live lab-like process of making them, can be particularly appealing to young visitors, and help engage them in discourses about the visible and the invisible, questioning the traditional patterns along which they conceive the role of imagination in this turbulent present.

How did the sudden event of Covid-19 pandemic, and the subsequent changes it caused in our lives and thoughts and views, affect the evolution of the project conceptually and emotionally?

By chance, the performative action of slide exposition and collection started on March 8th, 2020: the first day of lockdown in Italy. Just to be clear and honest, that was totally a coincidence. Nonetheless, it’s beyond doubt that Covid-19 had a strong impact on our work. Another quite mundane observation: due to the pandemic, the Jan Voxel group had more time than expected to focus on the project, reflect, read and perform, and so on. Conceptually, we can say that we have felt many times a close parallel between the eruption of the pandemic, as an illegitimate daughter of the voracity of the capitalocene, and the monsters and ghosts that we were handling on our slides.

We have also been discussing the possibility of a digital archive? What will the browsing system be like and what kind of narrative would you like to share with the audience?

The digital archive will shortly see the light. Again, it will be multi-faceted. The main components of the web site will be: an images archive; the critters map—a geolocalized map of all the places we visited (and will visit), which will contain real time digital elaboration of the PM data in that place at the viewer’s time, the voices and the sounds we collected there; the “Olga legge i critters” set of podcasts (an experiment in “looking through the critter images” we conducted with several adults and young adults, and which in our opinion proved to be a very interesting exercise in worldbuilding. To quote Matteo Meschiari, what we need more than ever is to try and find our way out of the anthropocene dystopian agenda is to start training again our organ of imagination; an—obviously incomplete and very personal—“anthropocene bestiary” more like a set of short sticky notes of our personal travel through the subject. In our view, the digital crittersroom.it archive will be another, different type of “multivoice” chorus about the connectedness of our present.

Where will the project travel next?

The project will premiere at Atelier Sì in Bologna on November 13th and 14th, after an avant-premiere held in Parma in October. The Critters Room in the form of a “digital archive” project has been selected as one of the winners of Residenze digitali 2021—a project by Centro di Residenza della Toscana (Armunia, CapoTrave/Kilowatt). Tutored in the last 6 month by Federica Patti, Laura Gemini and Anna Maria Monteverdi, the project will premiere in the week from 22 to 28 November. What about the future? We are actively researching new communities and local partners, new opportunities to contaminate and be contaminated: in our view, the Critters Room is still an ongoing project.