The Earthly Community as one Household

A conversation on ecology and feminist practices, fictions and future predictions

The history of Pangaea, or ‘Pangaia’ is a tale of the united old supercontinent that existed about 200-250 million years ago, combining all the currently separated continental blocks. The broken up fragments of Pangaea still bear the traces of that ancestral relationship. By making use of this geological metaphor, the exhibition Pangea United invites the viewers to try to imagine the Earth community as one household.

Artists taking part in the exhibition ask questions that help to move our ecological imagination. How can prototypes created within the art world teach us responsibility for the invisible suffering inflicted on other bodies? Can the logic of industrial livestock production lead to a similarly objectifying production of human life? What is the ecological potential of humble actions such as scrubbing floors with recycled fabric, seeding cress in public spaces, or organizing meetings where women can discover the burdens of patriarchy collectively? What can we learn from people who live in communities under threat of extinction, the so-called indigenous and folk cultures? What would be the value of goods, money and labour in a future devoid of any prospect of economic growth? Why will the borders, zones and territories that divide the Earth forever remain porous? The artworks assembled together in the exhibition space create a kind of essay on the subject of human attentiveness and consideration of the interdependence of different forms of life.

For far too long, categories such as usefulness in production and consumption, borders between states or the hierarchies of species, have been used to categorize various kinds of terrestrial inhabitants. Meanwhile, we need images, concepts and affects capable of expressing the more complex relationships that both unite and divide us. An awareness of the vulnerability and malleability of life incessantly intersected and stirred by others—other people and living organisms, machines and ecosystems—is the basis of a search for a community. Imposing the intimate scale of a household on the broad perspective of the planet creates a new way of looking at these relationships. Perhaps such a filter will allow us to look at them with care, that is with a responsibility for our own place, power and violence within the community and within the environment shared with those whom we might not know yet (from the exhibition press release). The following is a conversation with Pangea United’s curator Joanna Sokołowska.

“It is highly possible […] that we are no longer the citizens of any one particular state. Deep in our hearts we carry the countries we were born in, their chaotic diversity, rivers and mountain ranges, forests and savannahs, the changing seasons, birdsong, insects, air, sweat and humidity, grime and city noises, laughter, disorder, and confusion.”

Achille Mbembe, Politiques de l’inimitié, 2016

Tamás Kaszás, Lost Wisdom (Sci-Fi Agit-Prop), 2016-2019, installation detail. Courtesy the artist

Giulia Crispiani: The grounding intuition behind the exhibition’s realization is the earthly community as one household. What is the suggestion behind this proposition? What this universal conception of our geography would imply in terms of responsibility towards our shared environment?

Joanna Sokołowska: Pangea United is a proposition for visitors to exercise an ecological imagination. I have tried to moderate it in a way that I hoped could be helpful in mapping and taking care of the interdependencies within a rich and diverse web of life beyond such boundaries as nation, class, race or species. The variety of these “Pangean” relations and the magnitude of their habitat exceed of course the cognitive capacities of a human individual. This is why I am proposing the intimate, domestic frame of the household and artworks navigating across different, both singular and collective, tangible and abstract experiences of environment-making, to look at life on Earth. This strange, seemingly paradoxical scope might support the process of practicing curiosity and openness towards the multiplicity of forms of life and alterity within which human societies have to live.

The household metaphor implies also conceiving relationships based on care and responsibility for shared resources, and the necessity to acknowledge our entanglement with those whom we might not understand nor even notice. Therefore the assembly of artworks in the exhibition attempts to harness respect and empathic abilities of humans for other life manifestations, which we are connected with. On the other hand I would like to animate the sense of responsibility towards both power and violence by modern human societies inherent to their environment-making. Working with an ecological imagination entails mapping this multiplicity of relations that humans can have when dwelling in the world. It is about creating the conditions to imagine different patterns of cohabitation than those based on technologically advanced and automated exploitation of other humans, animals or resources. Ultimately, the household scale has a more practical dimension, as it aims at domesticating the interconnectedness of major challenges of our time, such as food, health, climate, work, energy.

Sin Kabeza Productions (Cheto Castellano & Lissette Olivares), Exhibition view. Photo: Piotr Tomczyk, Archive of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź

Tamás Kaszás, Exhibition view. Photo: Piotr Tomczyk, Archive of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź

Agnes Denes. Exhibition view. Photo: Piotr Tomczyk, Archive of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź

Let’s go back to the intention “to spark our ecological imagination” in the press release. Was it your idea to leave the questions open? Somehow, I like to see it in light of feminist quests vs capitalist statements/dialectics—from the female revolt manifesto “We wish to rise to be equal to an answerless universe.” Is that so?

I consider a feminist practice as the attempt to unlearn the attitude of using your intellectual power to control other minds, and rather trust your intuition, learn to step back and respect the sensitivity of the people you invite to the museum. In my case, apart from this legacy, it is a lesson I have learnt from the artists I worked with, from our curatorial work at the Muzeum Sztuki and from my spare time out of the office. Let me start with the latter. I don’t only read about the relationship nature-culture but also experience nature (yes! I dare to say “nature”). This practice helps me to encounter and accept the unknown, infinity, chance, chaos and the variety of patterns that organizes it. And consequently, it supports me in resisting this influential vision of the world as a set of tasks to be managed. I can’t imagine making an exhibition dealing sincerely with ecology, within the complexity of life in its various manifestations, and instrumentalizing artworks to simple answers or statements. Yet, I take responsibility for the selection and juxtaposition of artworks and try to arrange discreetly the flow of potential resonances between various pieces and suggest some clues such as, in this case, a reevaluation of care work, empathy and imagination as driving forces of (already existing) “Pangean folks.”

Christine Ödlund, Diana Lelonek. Exhibition view. Photo: Piotr Tomczyk, Archive of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź

Meanwhile, when I invite the public to the museum, I think that rather than teaching it is more hospitable to give them space to enter in dialogue with the artworks and to hear their own thoughts, feelings and find perhaps their own answers. They don’t need expertise in current intellectual debates including contemporary (post) humanities to be able to approach the exhibition. Likewise, I take care of the idiosyncrasy, poetic force of the artworks and their openness to unexpected encounters and emotions. Pangea United provides space for engaging with the present and long-term developments of some artists. For instance Jerzy Rosołowicz, Teresa Murak, Agnes Denes, Tamás Kaszás, Czekalska and Golec, Monika Zawadzki or Agnieszka Kalinowska are represented by several pieces. I do not trust artworks acting as conceptual toys. I understand the work dealing with imagination when mediated by aesthetic experience, as capable of rendering the sensible possibilities that we are not ready to recognize in a rational way yet, which we don’t have yet answers for.

In our overall work on the program of the Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź, we try to create conditions for viewers to sense the complexity of the aesthetic strategies employed by the artists. At the same time we look for ways in which we can exhibit and amplify the works’ resonance to politics and the present moment’s contradictions. Our recognition is in line with Walter Benjamin’s notion of a present “which has not yet become history, that which yet can become history.” We are interested in animating inquiries that are not limited to academic disciplines nor to automated, commodified rationale managed by seemingly “objective” algorithms. In a way I can see it goes against the grain of the semio-capitalism scripts as well as residues of patriarchal master discourses. Using all these big words, I have no doubts that our claims, tools and outreach are very modest. But I would be curious if you could let me know your thoughts on this considering your knowledge of feminist and environmental thought and…your background in industrial design.

Monika Zawadzki, Exhibition view. Photo: Piotr Tomczyk, Archive of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź

Monika Zawadzki, Exhibition view. Photo: Piotr Tomczyk, Archive of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź

Well, I would say that if there is something that art can do very well is indeed the revision of language: overcoming the paradigm, and creating a precedent in for instance pedagogical experiments or in aesthetics (not just talking about visual arts, but also music and literature or fashion), and in being together otherwise—obviously when the artists put themselves in relation to the world (vs the artist as conceptual genius, which personally speaking, I wish we could get rid of soon). Again it is not about teaching or selling a product but about suggesting, beginning, and most of all imagining. McKenzie Wark tweeted the other day “what if God would have given suggestions instead of commandments?” For me a feminist practice is something that allows something else to be set into motion. Indeed a question or a suggestion.

Although, when speaking of ecology today for instance—or fascism—it is even correct to speak of “imperative” in terms of urgency and care toward our “Pangean” household, folks and nonhuman animals. I really appreciated this approach at the exhibition Broken Nature at the Triennale in Milan, as it was not just exposing a problem or unfolding an issue, but targeting it and trying to propose solutions, prescribing treatments; when I was there I thought, this is an exhibition that kids and lawmakers should see, more than me and you. But then again the overall focus was more on design. In this sense maybe design can move beyond art… by means of tackling concrete issues, making claims and offering solutions. Yet, I wonder whether there could be a “post-fabulatory” art, an art post-Deleuze, for the people-to-come, where our imagination is bound to the idea of care—about the ecological imperative, beyond our dark times. Somehow if we’re having this conversation, it is already happening.

Considering this, many of the artworks presented in the exhibition are described as prototypes. Prototyping implies proposing a model, testing it throughout time, and the necessity to be approved/recognized by a collective. In order to be successfully implemented, the prototype requires a constant revision. Do you think there is an actual space for factual propositions or are these practices meant to remain in the speculative domain?

Actually, the concept of art as a laboratory and the ensuing notion of the prototype is a recurring idea in our work with the legacy of the avant-garde collection of the Muzeum Sztuki and our curatorial framework for 2019. We invite contemporary artists to draw on selected pieces from our collection and to reuse them in ways they find relevant to be shared with our visitors. They turn the museum’s collection into a pool of practices and methods awaiting updating, reevaluating or even relaunching them. In a more long-term perspective we have been dealing with propositions and designs that could be implemented in a way relatively close to the industrial function of a prototype, as well as with those who remain in the speculative domain. Also, we deal with the grey, porous zone that transgress divisions between speculation, usefulness, utopia and recycling. Personally, I see the most profound—and at the same time the weakest agency of modern and contemporary art as a kind of prefigurative politics, an anticipation of a community that might eventually acknowledge models proposed by artists. But I do not impose on models proposed by artists a demand for direct application in terms of achieving measurable social changes.

My attitude is close to Deleuzo-Guattarian concept of minor literature, calling “the people [who] are missing” the “people to come.” Deleuze reminds us that “the fundamental affinity between the work of art and a people that does not exist is not, will never be clear.” I accept this ambiguity and don’t want to target the community to buy and apply the prototype. At the same time the artists taking part in Pangea United who model future communities—for instance Czekalska & Golec, Monika Zawadzki, Tamás Kaszás, Sin Kabeza, Diana Lelonek, Jerzy Rosołowicz, Agnes Denes or Artavazd Peleshian don’t propose anything unthinkable, overwhelmingly complicated or new. They modestly recycle and reevaluate practices that have already existed but are unprofitable or uncomfortable for the current, hegemonic rationale and remain thus marginal or barely survive under threat of destruction. Thus, I would say that these prototypes are untimely, they render sensible the possibilities, that make no sense under current, toxic conditions of production.

Their untimeliness resonates in my opinion with Walter Benjamin’s concept of time and more specifically with Giorgio Agamben’s concept of contemporariness. We evolved the latter in relation to contemporary art together with Jarosław Lubiak on the occasion of the exhibition Untimely Stories at Muzeum Sztuki. Agamben identifies the untimely with the contemporary: those who are contemporary go beyond their time, beyond the present moment and the pragmatic logic of punctuality. Those who inscribe themselves perfectly in the present are unable to see it—the contemporary dispute around their time, thanks to which they are able to properly recognize it and act accordingly, that is, by keeping up with a subjectively-established truth about it. In this sense, the works presented in the show are untimely. They become contemporary because they go beyond the present moment. They offer narratives that signal the consequences of our past and those to come. They do not aspire to be functional solutions for current issues.

Czekalska & Golec, IMPLANT IHS*, 1995–2018. Architectural incrustation* Insect Home System. Courtesy the artists

So, how do these speculative practices get to develop future predictions and fictions from current elements and histories? Can you list some examples?

For instance Czekalska & Golec, Artavazd Peleshian or Monika Zawadzki envision different futures in which the ongoing mass violence people inflict on vulnerable bodies of other animals will not remain without consequence. It could be future communities and social life much wider than those defined by human history as depicted in Peleshian’s short, experimental film Inhabitants [Obitateli]. Shot in Soviet Russia in 1970, the film makes use of Soviet avant-garde cinema’s aesthetics strategies, endorsing the environmental transformation as a result of people’s labour (one of the most notable example of this tradition is Dziga Vertov’s 1926 film, The Sixth Part of the World). However, Peleshian’s eponymous inhabitants are not people, but wild animals, depicted both in vast herds and individually, as if they were one, large organism set in motion by a common effort. No humans are visible in this community’s universe, and yet their presence—the alleged source of the animals’ visible panic—is suggested through the author’s use of “distance montage.” It’s a very rare and untimely perspective considering the context of the Soviet cinema.

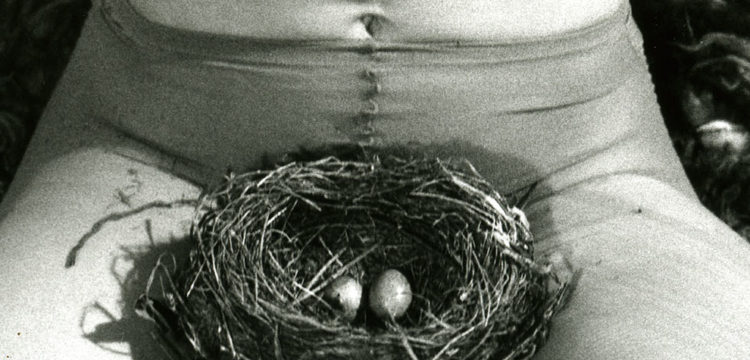

The experience of witnessing invisible violence exercised on a nonhuman species by humans pushed Czekalska & Golec to prototype devices for practicing attentiveness and empathy. These devices are supposed to protect insects from the current almost unnoticeable and banal destruction that happens through trampling on them. They are very simple and could be actually already applied and mastered through time but now they look absurd, because majority of human societies are not (yet?) ready for such attentiveness. Likewise, Zawadzki designs objects anticipating bioethics of relations between human and nonhuman animals, objects and machines that dislocate the current order. One of the critical points of reference for her work is the industrial breeding of animals for meat. In response to the fact that this violence has long become rationalized and widely accepted, Zawadzki designs generic models of the future humans who will be deprived of their uniqueness, their individual features and their existing power. The machine-based, technologically refined violence they inflict on others in order to conquer the world will eventually come back to haunt them. As a result of the objectification and dismemberment of the bodies of others, humanity itself has become objectified and fragmented. For Zawadzki, this destruction is, however, creative—a chance for a new but unclear beginning. Working through the multiplicity of questions and possibilities, in all these cases the artists remain clear about one thing concerning the matter of “the people to come”—the division between body, flesh and cadaver, the muzzle and the face, bios and Zoe will be radically dislocated.

Diana Lelonek, The Center for Living Things, 2016, detail. Courtesy the artist

Are some of these practitioners taking their prototypes out of the museum/white cube? If yes, how?

I think all of them have this chance, if they happen to affect the public, animate their thoughts, feelings, subconscious. And of course, most of the artists taking part in Pangea United draw on variety of resources and knowledge beyond art history and other academic disciplines. The borders between the agency and functions of artworks in museums, white cubes, “in the streets,” applied in activism, every day life or smuggling into scientific discourses are very porous. I see these channels as complementing each other. Inside, outside and in-between—I would actually suggest abolishing these divisions.

For instance Diana Lelonek has been testing her skills to support diverse environmental initiatives such as Climate Camp and “just transformation” of a region in Poland with intensive coal mining. For the exhibition I chose an apparently more classical work of hers, the vitrine with excerpts of the pata institution. The Center for Living Things, established by the artist in order to collect and study the relations between the used, discarded objects and bacteria, plants, fungi, worms and other organisms of the ecosystems. However, the major seat of the Center is the Botanical Garden of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Poznań, where the artist stores the bulk of the objects, and works together with scientists on the creation of descriptions and taxonomies of the collection. Diana Lelonek makes use of the scientific findings outside of the white cube to connect them with social and cultural discourses. To this end she makes use of the openness and transdisciplinary porosity of art institutions.

Agnieszka Kalinowska, exhibition view. Photo: Piotr Tomczyk, Archive of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź

Another artist in the exhibition, Tamás Kaszás has experiences in participating to diverse anarchist and civic movements in Hungary, which have nourished much of his works. Now he lives on an island next to Budapest where he and his family grow a permacultural garden and experiment with autonomous, self-sustainable life. His art can be perceived as a model for visual culture representing the future “Pangean” societies informed by “folk science,” grass-root, anarchistic and environmental civic movements and experiments in self-sustainability. Tamás Kaszás himself lives close to the values he represents in his art. Taking care of his loved ones and their environment is often at odds with the demands of global mobility, networking and availability in the art world. It’s a privilege to work with artists who have such diverse experiences and who are able to bridge a notorious gap occurring in the contemporary art field, the gap between performance and representation/rhetorics.

Nevertheless, I believe art institution should in particular take care of these fragile, untimely and thus sometimes ambiguous or unclear visions. They are often too complex, too vulnerable to become easily socialized, domesticated to circulate quickly and to affect immediately. But I think they are precious and we should protect this faculty of the human mind in particular considering the mass production of automated, goal-oriented subjectivities.

Jerzy Rosołowicz, exhibition view, Photo: Piotr Tomczyk, Archive of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź

Jerzy Rosołowicz, exhibition view, Photo: Piotr Tomczyk, Archive of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź

I like to think of the artist—or the curator—as a mediator, a stirring agent that can bring together and benefit from alternative cognitive systems, in order to foster and implement trans-disciplinary knowledge and strategies beyond the predominant economy of profit. What do you say about this possibility?

As curators or artists we have a privilege and a certain autonomy to negotiate our position in regard to the predominant economy of goals, targets, measures, profits. We can explore areas we are ignorant about. We are free to connect and reuse diverse artifacts, disciplines, tools, forms. We are free to work with untimely ideas and useless knowledge. However, there is a price for this freedom and autonomy. We are at the margins of society. I do not think that the predominant economy can be really challenged by our activities.

The potential shifts in perceptions and imagination animated by artists and exhibitions I have discussed in my previous answers can of course resonate with much larger social movements and cooperate modestly with these forces, but I would not dare to describe contemporary art as a unique stirring agent implementing trans-disciplinary knowledge informing new economies. In terms of every day practice, structures and organization of work contemporary art system seems to be far less literate in alternative economies and education than multiple grassroots civic and activist movements.

Alicja Rogalska, (Im)personal development, 2015. Video still. Courtesy the artist.

In this sense, considering Jerzy Rosołowicz’s idea that art carries a positive value in itself, again how does this relate to the relationship between art and other disciplines?

Actually Jerzy Rosołowicz ouvre points to the limits of art as mediator among other disciplines as other disciplines did not reciprocate his interest in them. But first of all, he was critical of the idea of progress and the human desire to change the world. He was convinced that changes perceived by modern societies as positive ones end up with the negative environmental impact. In his theoretical texts Teoria funkcji formy [Theory of Function Form] (1962), O działaniu neutralnym [On Neutral Action] (1967), Próba odpowiedzi na pytanie, co to jest świadome działanie neutralne [What is a Conscious Neutral Action? An Attempt at an Answer] (1971), he proposed the idea of art as a “neutral action” that could introduce order and peace by “neutralizing negative values with positive values.” Rosołowicz harboured an utopian hope that—alongside art—cybernetics, urban planning, architecture, sciences, psychology and sociology could be particularly helpful in neutralizing the civilizational tensions and antagonisms. He created works resembling interdisciplinary scientific prototypes stimulating “neutral action,” such as Dew collector, Creatorium of the Millennium Stalagmatic Column or diverse Neutrdoms. In the series Neutronicons from mid-1960s, Rosołowicz experimented with optical glass as an instrument for practicing a “neutral” view of reality. Neither constructing nor altering anything, they simply bring attention to the relationships woven from light, shadows, reflections, eyesight and the matter, among which the seeing bodies move. Although Rosołowicz drew on knowledge from diverse disciplines including even teleradiesthesia, his visions were not meant to be implemented and were not taken seriously by scientists, or architects. Ultimately, it is clear that they had different goals than creating devices and environments for disinterested contemplation.

Tamás Kaszás, Lost Wisdom (Sci-Fi Agit-Prop), 2016-2019, installation detail. Courtesy the artist

I love the idea of considering our shared environment as a household, as if we would be all be mothers—traditionally speaking yet breaking the binary that only women are mothers. This is inserting a high load of responsibility even on the act of imagining such scenario. Can you describe, more or less in details, if this would actually be the case, how would that be?

It’s not a utopian scenario, nor rocket science at all, but making sense of the emergent holistic, systemic approach to life. It’s about asking very primal and naive questions that may lead—let’s say—to associating the pain of human parents mourning their children and the pain of cows separated from their calves, or recognizing the relationship between the wealth of companies extracting world’s resources and the devaluation of daily labour of caretakers, teachers, nurses or farmers… As a cultural worker I try to display stories that help to connect the dots. Pangea United and the idea of the shared environment as a household has developed from the previous exhibitions I had curated at the Muzeum Sztuki Workers Leaving the Workplace, All Men Become Sisters, Exercises in Autonomy. Tamás Kaszás featuring Anikó Loránt (ex-artists’ collective), Assemblages. Angela Melitopoulos and Maurizio Lazzarato and For beyond that horizon lies another horizon in Edith-Russ-Haus für Medienkunst, Oldenburg. With the hindsight I can see them all as one exhibition, featuring artworks inhabiting already the world, in which environmental questions are related to labour, gender, politics, in a holistic manner.

For instance you can sense it if you look at the piece by Alicja Rogalska (Im)personal development documenting a coaching workshop with a group of female residents of Łódź seeking for professional and personal change. The coach she invited to work with the group did not use corporate tools and techniques to promote individualistic thinking about and individual success and self-development. Instead the event sought to capture the shared, structural (sisterly?) experiences of women under precarious working conditions. During the meeting the participants started expressing desires for abolition of national borders, compulsory paternity leave and the concern for ecological education of school kids as interrelated issues that would improve the quality of their lives.

Needless to say, the scenarios for inhabiting the Earth responsibly and carefully have already been implemented worldwide in variety of environmental initiatives. Personally, I have experienced this happening in the Camp for the Forest organized against logging of the primeval Białowieża forest and in the Climate Camp in Świętne, Poland. The activists who are the driving forces of these initiatives moderate assemblies of people for which it is increasingly clear that their engagement in environmental issues must be complemented by overcoming sexism, racism, classism and other sorts of violence and abuse.

Artavazd Peleshian, Inhabitants (Obitateli), 1970, film still. Courtesy FILMS SANS FRONTIERES, Paris

Can we agree when we state that the ecological concern is an inherently feminist issue?

It’s a complicated relationship. On one hand there is a strong legacy of Western feminism as a history of escaping the faith of the collective Zoe—mindless vitality of nature colonized by patriarchal reason. Contrary to this one, we have a tradition of Mother Moddess or Mother Earth narratives identifying women with nature. Personally, I am interested in feminisms beyond their comfort zones, that contribute to changing the paradigm of production and social reproduction based on exploitation of what Jason W. Moore identifies as “cheap nature.” In Moore’s view, the mechanism of the accumulation of capital demands the production and appropriation of areas of life that are set aside as extra-social and extra-economic; it is here that one encounters phenomena such as slave labor in European colonies, the industrial exploitation of animals, unpaid or low-paid labor performed by women and migrants, and the exploitation of entire ecosystems. I feel affiliation with feminisms being part of the larger “Pangean imagination.”

Mona Vătămanu and Florin Tudor, The Order of Things, 2011–2012, film still. Courtesy the artists

In the work The Order of Things by Mona Vătămanu & Florin Tudor, in the poem Celebrating our Freedom by the Zimbabwean writer Chirikure Chirikure one line reads as:

“Celebrating the political freedom of my motherland

Shall I celebrate with wine, music and dance?

With my broken back and bruised spirit,

Shall I celebrate with wine, music and dance?

No! I shall celebrate by casting my eyes further,

For beyond that horizon lies yet another horizon.”

I like the idea that we could/should consider the possibility for a future as something to celebrate?

Me too. Pangea United aims at overcoming the comfort of celebrating the catastrophe to come. Chirikure Chirikure’s poem is a mesmerizing appeal to take responsibility for future generations, to have the courage to move beyond the cycle of colonial violence, to celebrate the skills and power we have already in our hands. In their film Mona Vătămanu & Florin Tudor take up the specific cultural context of the poem and inscribe it into a different, enigmatic space-time. The film’s editing is based on the parallel interweaving of two loosely connected threads. One of them shows the baking of bread in a Middle Eastern bakery in Berlin’s Kreuzberg. The second scene depicts some kind of threatening exercises involving a globe, first formed in the shape of a pyramid and later set on fire. The sound of recitation of the poem Celebrating our Freedom links these juxtaposing scenes. The call expressed in the poem to see the horizon of hope visible right behind the actual one seem to finally resonate with the images and sounds of the labour of baking bread. Perhaps this horizon is already given to us, and we already know what to do, but we need to look closer to see further ahead?