The Clouds Have Fallen

A conversation with Soukaina Abrour

Part of If Body 2024, Storage Almost Full: the Clouds Have Fallen is a solo exhibition by artist Soukaina Abrour presented at Lateral Roma and consists of an environmental installation that combines video, sound and textile elements. The work is born out of a re-elaboration of fragments drawn from the artist’s digital archive, alternating traces of her personal experiences with materials found online, all of which have been selected and accumulated over time.

If Body is a public visual and performing arts program that focuses on the body as an artistic language and learning methodology based on experience and participation. Conceived and curated by Sara Alberani, Marta Federici, and Chiara Siravo (LOCALES), this year’s edition is titled Living Fragments. Through seven events, it presents new performances, talks, workshops and exhibitions that explore the cultural, social, and political meanings associated with the body and corporeality. This edition features interventions by Aliaskar Abarkas, Soukaina Abrour, Adelita Husni Bey, Noor Abed & Lara Khaldi (School of Intrusions), Emily Jacir & Michael Rakowitz.

The following is a short review by Giulia Crispiani, followed by a long conversation with the artist.

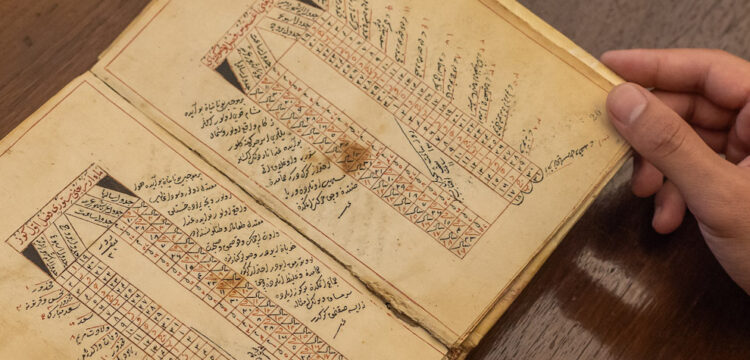

When the cyanotype was discovered in 1842, Sir John Herschel expected that photochemical reactions would reveal, in forms visible to the human eye, the infrared extreme of the electromagnetic spectrum and the ultra-violet or ‘actinic’ rays. This slow-reacting formulation remained a widely used medium for photographic printing to fix light on paper and textile while it produces negatives of objects and images.

Soukaina Abrour’s cyanotype textiles, part of the exhibition Storage Almost Full: The Clouds Have Fallen curated by Locales and currently on view at Lateral Roma, got me thinking about the duration of a reaction, how long does it take for an image to impress itself in my mind, and in turn how long will it stay? Nowadays we often use the expression “to be bombarded by images”—and currently the database I am personally exposed to has a lot to do with actual bombs. Soukaina’s work courageously acknowledges this, by standing with both (or all of them whatever the number) feet in the mud of contemporaneity, while, quite literally, whatever we know as most familiar, our paraphernalia, burns before our eyes. When the storage is full, what do we do with our memories?

Soukaina Abrour, Storage Almost Full: The Clouds Have Fallen, If Body 2024, commissioned and curated by LOCALES, Lateral, Rome, 2024. Photo Roberto Apa, courtesy the artist and LOCALES.

As stated in the press release, the burning of the piece of furniture shown in the video work can be a witness to a post-break-up ritual, but also, among the rest of the visual cues and within the filmic narrative, a reference to a much broader range of meaning within the spiral of the overcoming of a suffering, a celebration of a loss, a mourning. The main video in the tryptic is a bold montage of private and social-media-sourced images, accompanied by a text/voiceover which indeed spirals back and forth from the personal to the universal. The first topic it touches upon is love—a very dear one to me at the moment, because I am interested in seeing love beyond the relationship: to consider it in its revolutionary potential in which love means freedom, and (armed) resistance means love. In Soukaina’s spiral, from the fire ritual we move straight to the footage of violence and destruction in a time of genocide, and the axis is the proof: if the piece of furniture that burns is the physical trace of a feeling, the images that follow serve as the evidence of injustice. I feel this spiral has no end, we can reach the bottom of it, and still keep on spiraling back, then up and down, over and over again.

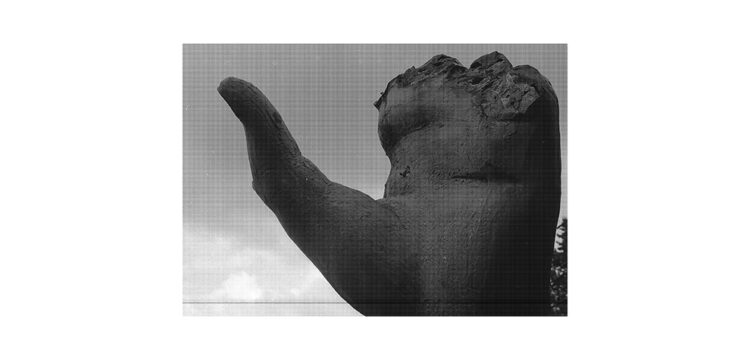

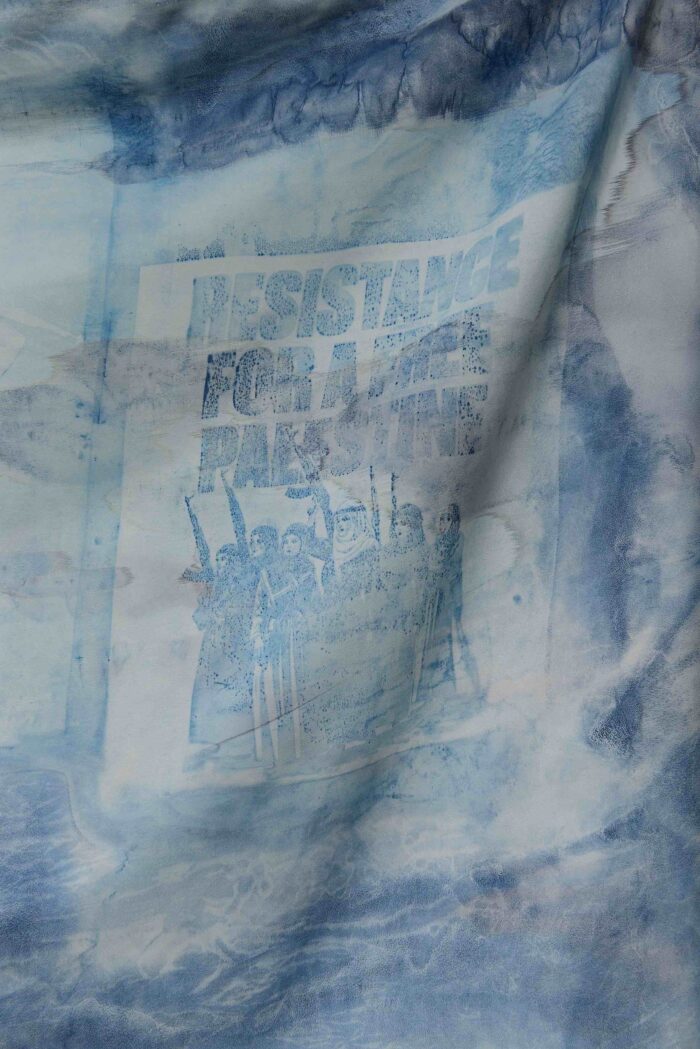

On the two other screens present in the exhibition, two different videos on loop underline the ephemerality of the cloud. The cloud here serves several purposes, from the material atmospheric one of concealing light, to the metaphorical naming of a (very physical) fascist and censorious digital storage. If we are made of our memories, can we ever become full? But I would also add another layer to the list of purposes a cloud can have, that is the spiritual visualization of an after-life, a barzakh that welcomes all souls awaiting judgment, where the new life that awaits to be born bears struggle and liberation. That is where love becomes universal. While the world as-we-know-it burns down, the whispering voice urges us to pick up the struggle. The hand “full of stones” is a wink to all the comrades who already know. The same goes for the textiles. We do recognize the posters that are printed on them from the streets, from social media, we have already seen them plenty of times, and we are glad to see them here as well. We’re happy this white cube has become, for a while, a place of protest. The way they are paired, next to each other, already turns the event into an archive, it affords a certain materiality to a history that is not easy to process while such a heavy present unfolds. The chains that are used for hanging, they speak for themselves, but I did take that detail very seriously.

To return for a moment to the cyanotype, the procedure and the duration of their fixing acquires a materialist quality. I can physically perceive the image as a photogram, that is to say an object placed on a light-sensitive material, in the space it occupies and the way it fixes slowly, becoming information, which is oftentimes quite emotionally loaded. In the case of these posters, as manifestations of actual collective resistance, I consider them to be sources of light in a very dark backdrop. This is clearly a time when we all feel entrenched in the difficulty, if not the impossibility, of speaking about extreme violence and oppression, whilst we have the moral obligation to imagine a reality beyond all this, thus we must strive to amplify and look for practices and words of justice and freedom—if “we have failed the words”, as Soukaina says, we can still hope to find each other’s hands full of stones.

Soukaina Abrour, Storage Almost Full: The Clouds Have Fallen, If Body 2024, commissioned and curated by LOCALES, Lateral, Rome, 2024. Photo Roberto Apa, courtesy the artist and LOCALES.

Giulia Crispiani: “Give me your hand, and I hope it’s full of stones” — where does one even begin to make a work in a time of genocide accompanied by such an openly blatant obliteration of truth?

Soukaina Abrour: Mmm, where does one even start answering this question? Maybe I’ll begin by saying that a person starts doing work in times of genocide because this is the shit they know how to do. Still, when I write “Give me your hand and I hope it’s full of stones”, it is an invitation to organize and fight collectively, outside the galleries, outside the clouds, outside the comfort zones. I believe it is time to hold hands, as tenderly as we can, and be ready to throw stones.

As Toni Cade Bambara said when asked “What determines your responsibility to yourself and your audience?”: “I start with the recognition that we are at war.” I would add that it is also a war over truth and that today, as in every war of liberation, the truth lies in the hands of those who resist, by any means necessary.

Also, if we want to dig a little into this question—acknowledging that any answer of mine will not be sufficient to even begin to scrape away at the gigacrust of this topic—I’d say that the collapse of truth is nothing new. It has accompanied the capitalist imperial project since its inception. In fact, I would say it is a foundational element of its success. True life cannot exist in the fabricated fiction of imperial extractivist expansion.

Soukaina Abrour, Storage Almost Full: The Clouds Have Fallen, If Body 2024, commissioned and curated by LOCALES, Lateral, Rome, 2024. Photo Roberto Apa, courtesy the artist and LOCALES.

But the masks are falling, the genocidal capitalist necro-empire is exposed and all its propaganda advertising of “progress,” “freedom” and “peace” is crumbling as we witness the daily horrors perpetrated in Palestine, Congo, Sudan, and countless other places. Again, it is nothing new. But we are at the peak of this cursed society that we built on the blood of countless lives. Each of these lives deeply curses the empire.

Subaltern people living in the so-called West have always smelled the stench of the lies, the glitch in the matrix (Matrix as in “The Third Eye” by Sophia Stewart—a black writer—not the Warner Bros exploitative plagiarism). This is because we also curse the empire since we don’t fit into the model of the imposed “truth” and we pay highly and daily for the consequences of this “inadequacy.”

I do not believe in the art world as a driver of change, because as it exists now, it is a healthy product of necro-imperialist capitalism. But I do believe in occupying these spaces to talk about the Truth, to change the content, and to question perspectives. Unfortunately, I have this uncontrollable drive–which inshallah I will cure–that pushes me to relate thought, materials, and space, and to produce installation works that make me an “artist” in its contemporary sense, a role I somewhat despise. I would call myself more of an art-worker.

I’d be dishonest if I didn’t say that I also believe that art is one of the few spaces of freedom for experimenting and exploring new ways of existing, expressing the self, and relating phenomena in new ways. So potentially art could be super generative for imagining new futures. In addition, I believe that art should also be a space free of connotative categories that frame the artist just by their identity etc. etc. as it happened with tokenism and other forms of essentialization in the past years. But it’s difficult to experiment and enjoy the poetics of new forms, born out of playing and exploring, when you start out by recognizing that we are at war. The duties change.

Soukaina Abrour, Storage Almost Full: The Clouds Have Fallen, If Body 2024, commissioned and curated by LOCALES, Lateral, Rome, 2024. Photo Roberto Apa, courtesy the artist and LOCALES.

How did you treat the images? From the archival phase to their rearranging in space, via the video works.

It’s become a common refrain to talk about the bombardment of images and our voracious consumption of them, but that’s where I start. I’m completely at the mercy of doom scrolling, whether on social media or while diving into the nostalgic cradle of archival memories.

On social media, I tend to meticulously archive everything I see into countless folders and subfolders – e.g.YouTube playlists and saved folders on Instagram. This behavior has fine-tuned the algorithm’s ability to lead me into the content loops that captivate me the most. Unfortunately, two years ago, I caught a virus that allowed hackers to access and abruptly delete all my social media platforms. Overnight, I lost accounts that I had been using since 2012/14. Despite all my attempts to resolve the issue with Meta and Google—going so far as to send my ID and photographs of myself to these opaque entities—nothing worked. This experience has undoubtedly altered my relationship with these tools. My reflections, which once focused on the inherent violence within the framing of images and the trivialization of their dissemination, as well as the centralized control over this dissemination, have deepened. My hatred for these ultra-convenient, organized, and user-friendly platforms has intensified, yet I have no resolution for this anger—only complaints—while I continue to use many of their services.

When it comes to my personal archive, I have a different obsession. It stems from a continual return to the chaos of low-quality snapshots taken over the past 10 years—a time lived in hyper-velocity and anxiety. I try to slowly verify the visual impressions of spatial and emotional geographies, of layers and discontinuities, seeking to capture the images that could best represent the emotions I felt at the moment of capture and the futuristic imagination they allowed me to speculate upon. This obsession applies to the documentation I created in early 2022 of the burned furniture. It kept resurfacing, even just before I got the virus, and I had begun working on it again, primarily through video. But the virus wiped out all the work I had been doing. Luckily, the original files were spared.

Two years later—now—my reflections on this sense of ending, which I was already strongly perceiving back then, have deepened significantly. Inevitably, my thoughts have returned to that image, connecting my use of personal images with those circulating online. I’m also questioning the value of digital images versus their experience in the material world. This led to my desire to experiment with cyanotype printing. I’ve often worked with different printing methods as part of a process to transform archival elements into an imaginative frame distinct from their origin. I believe that materializing an intangible element—whether a thought or a constellation of pixels—gives it a less precarious, more tangible sense, by anchoring it in the limited three-dimensional world rather than in the undefined space of thought or the web.

However, with cyanotype techniques, I’ve been able to maintain the elusiveness of meaning, despite—perhaps especially because of—fixing the digital image into a material form. The video and the cyanotyped fabrics are intended to create paths within the space and focal points for the gaze, where the almost didactic chromatic shades of these fixed and unreadable images in the fabric, are juxtaposed with the as well elusive but frenetic images of the videos. Video and post-production have always been mediums that allowed me to explore and construct an imagined narrative starting from an image constrained within a frame.

Soukaina Abrour, Storage Almost Full: The Clouds Have Fallen, If Body 2024, commissioned and curated by LOCALES, Lateral, Rome, 2024. Photo Roberto Apa, courtesy the artist and LOCALES.

The cloud as a literal storage space and as a means of control, as a depository of all our memories and life-moments. Is it a recurrent character in your practice at large? Could you tell us a bit more about that?

No, the cloud as the main character appears for the first time in this work. However, it has always been a fundamental element in the narrative imagery of my previous projects. I have often explored the concept of waste as a dominant feature of late capitalism. “La munnezza è oro,” (“trash is gold”) as they say in WuMing’s Previsioni del tempo.

In my practice, the element “waste” manifests both materially, through textiles, and as a socially constructed category, along with digital waste and its tangible impact. When it comes to archiving, my thoughts turn to the recklessness with which people—including myself—take photos without considering where these images end up, most of which could be deemed waste. Yet these discarded photos serve as prime fodder for feeding data collections on faces, objects, and landscapes, refining AI’s ability to recognize and categorize everything. How these categories will be used ultimately depends on the highest bidder. And most of the time the highest bidder always has something to do with blood—and exploitation—money.

Soukaina Abrour, Storage Almost Full: The Clouds Have Fallen, If Body 2024, commissioned and curated by LOCALES, Lateral, Rome, 2024. Photo Roberto Apa, courtesy the artist and LOCALES.

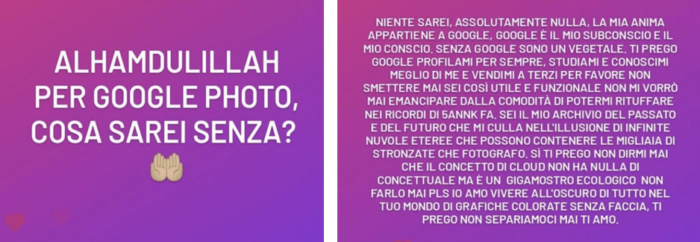

When creating a piece, I often draw on fragments from the chaotic mass of images, identifying the speculative potential to craft a new narrative. Initially, this was an exercise in reconciling with the emotional and visual landscape of the diaspora, particularly because this method was reserved for archiving my last family trips to Morocco (2015-18). It also served as a way to confront the overwhelming wall of images accumulated over the years in the terrifying, daunting, yet captivating context of Google Photos. The goal was to select a few meaningful images, delete the rest, and archive memories in an alternative way, thereby breaking free from the convenience offered by this turbo-capitalist, Zionist cloud. I’m still caught in its grip.

After the hacking incident I suffered in 2022—which I mentioned earlier—after which only my Google Photos cloud survived, I wrote a macabre ode to my savior and tormentor on my Instagram stories: Alhamdulillah for Google Photos 🤲🏼, what would I be without it? Nothing, absolutely nothing. My soul belongs to Google; Google is my subconscious and my conscious mind. Without Google, I am a mere vegetable. Please, Google, profile me forever, study me, know me better than I know myself, and sell me to third parties. Please, never stop—you’re so useful and efficient. I will never seek emancipation from the convenience of diving into memories from five years ago. You are my archive of the past and the future, lulling me into the illusion of infinite ethereal clouds capable of holding the thousands of trivial things I photograph. Yes, please, never tell me that the concept of the cloud is devoid of any conceptual meaning, that it’s an ecological monstrosity. Please, don’t do that. I love living in blissful ignorance within your world of colorful and happy graphics. Please, let us never part—I love you.

I recognized one of the posters on the fabric (by my dearest comrade Golrokh Nafisi), where did you source the images and, again, how did you work with them?

I gathered some over the past few months from various social media platforms and copyleft pages. Part of it is a personal archive that has merged into a collective archive on a Telegram channel born out of a sticker meme creation workshop led by Noura Tafeche, Seba Pala, Ismael Condoii, and Khadim Loum, in which I collaborated during some of the workshop sessions.

There’s an article written by Noura Tafeche and Basem Kharma titled “Ecosystem of an Arab Meme” in the latest issue of ArabPop, dedicated to Palestine, which explains very well the value of memes in the online sphere, particularly for Palestinian, Arab, and Arabophone communities. These memes express their zeitgeist without seeking the approval of the Western gaze or “del perbenismo elitario che si è senilizzato alla domanda ‘condanni il 7 ottobre?’” (as Noura Tafeche puts it in the article).

I started from these reflections, which have been developing for years, but in recent months, the significance of meme and poster content has become particularly evident. It plays a crucial role in crafting a narrative that escapes the censorship and the biases of mainstream media. Many of the posters featured in the cyanotypes—some legible, others not—originate from libraries of collective graphics designed to enable wide dissemination through postering and sharing. The way I’ve used these images follows the process I explained in my previous responses.

Soukaina Abrour, Storage Almost Full: The Clouds Have Fallen, If Body 2024, commissioned and curated by LOCALES, Lateral, Rome, 2024. Photo Roberto Apa, courtesy the artist and LOCALES.

“There’s no new life without struggle, there’s no new life without liberation”—how do we take back language?

Well, I think we are doing it. With the collapse of the fabricated truth perpetuated by the necro-imperial system, the past few months have seen many voices rise to reclaim terms, analyze others, and debunk all the lies upon which this empire was built. Take, for instance, the word “terrorist,” which until recently was almost interchangeable with the word “Arab.” I grew up hearing myself called a terrorist, bombarola, allahuakbar etc etc and I am not just talking about elementary and middle school, but also at university (yes, the progressive Italian academies of fine art…)

But now there’s the discursive spaces in which to debunk and ridicule this suprematist thinking. While some still hold on to these kinds of associations—and it’s not just right-wing, conservative, or liberal individuals, but also a large portion of those who consider themselves “leftist”, even radical, who on these matters often reveal themselves to be as narrow-minded, self-centered, and dogmatic as the most obtuse democristiano (Christian Democrat)—a significant effort is underway to reclaim language.

It’s a challenging task because language itself is a tool of oppression and control, spanning from everyday verbal violence to national and international legislative language used to oppress and create categories of first- and second-class human beings, all under the pretense of being a system of laws based on equality and the so-called “human rights.”

Liberation struggles also teach us how theoretical, intellectual, poetic and linguistic frameworks evolve alongside resistance movements, becoming integral to the struggle, alongside armed resistance. Consider, for example, the liberation of Algeria or South Africa and the intellectuals who were involved in shaping the struggle, its narrative, and its future through language. Without forgetting how many figures of the highest level of avant-garde thought Palestine has produced in its century long struggle.

This work is an archive of fragments, how do you usually deal with fragmentation?

I use fragmentation as a tool to combine different pieces from various elements, creating an overall vision that seeks meaning, while still preserving the individual complexities of each fragment and the opacity of meaning that defines them as separate parts of something else. I believe this approach offers intriguing imaginative potentials. Fragmentation, beyond being a working process through the archive, is also a part of who I am and how I grew up.

I recall discussing how subaltern figures in the west have always sensed the stench of lies and the glitches in the matrix. I believe this is also related to the fragmentation experienced by people, for example, with a migratory background, and maybe also poor. Growing up between vastly different cultures and a strong class difference, they sense how each one of these believes in different truths, leading to fragmentation in constructing their world, partly because one culture tends to dominate and oppress the other, calling it “integrazione.” Similarly, queer individuals inhabit their bodies in a way that external structures deem erroneous, causing a rupture and fragmentation in their existence.

In my work process, I often feel the need to gather these broken pieces and find a way to keep them from being wasted. Sometimes, it’s enough to glue one fragment to another; other times, the fragments need to be finely ground into sand, mixed with a little water—sometimes tears, sometimes blood—and shaped into a new form.