The Body, The Plane, The Camera

A visit to “The Last Terminal: Reflections on the Coming Apocalypse”

The program The Last Terminal: Reflections on the Coming Apocalypse is currently on view at Rib, Rotterdam. This review is based on Part 1 — Survival of the Fittest: the big toe of little big man. The next iteration Part 3 — The Phantasy opens on March 26th, 2022.

Imagine a headline about the process of evaporation: Water levels fall, memories surface.

Wildfires caused by sparking cables, an ever-worsening drought, flashfloods, and mudslides dominate the mediascape when it comes to news about California’s climate emergency, and the picture of a state out of balance becomes all too clear. At the same time, a less dramatic but equally consequential process is taking place in water reservoirs in places like Lake Shasta and Lake Oroville, their names right out of an old Hollywood screenplay. Little rain and rising temperatures mean water reserves fall lower and lower as they are drawn up and absorbed into the atmosphere. When water levels fall, it seems, many things surface.

I came across a story last year about the discovery of the remains of a plane that went down in 1986 in Folsom Lake, California. Because of extremely low water levels, the wreckage of that non-fatal crash resurfaced, but much to the underwater surveyors’ disappointment, it wasn’t the plane they had been hoping to find. For over 50 years, they had been looking for a plane that crashed in 1965 on New Year’s Day. In that case, only the pilot’s body had been recovered, but not the plane.

Thinking about how hierarchies of intrigue are formed, and about the idea of a body without a plane, I start my trip to The Last Terminal: Reflections on the Coming Apocalypse, Part 1: Survival of the Fittest: the big toe of little big man, a long-term program at Rib, Rotterdam curated by Maziar Afrassiabi. No longer interested in making programs with a planned end, Afrassiabi acknowledges the process of changing, evolving narratives within overlapping and entangled exhibition practices.

I begin at the very back corner of the space to watch two films by Albert Lamorisse screened on side-by-side monitors. Le vent dex amoureux/The Lover’s Wind (Baade Saaba, in Farsi) has original sound, and we hear the voice of Manuchehr Anvar, who reads the English script, telling the story of Iran’s landscape from the perspective of the lover’s wind. Music and the sound of the wind complement and help carry the image. The other film—the postscript— title unknown, has been muted. We see Iran’s sites of technological development and industrial power, and a visual fixation with the machinic, the rhythmic and relentless implementation of power.

The dialectic of these two—“this” and “that”, to borrow words from Marije de Wit’s adjacent sculptural work—exposes the troubled relationship between art-making and compromise. In the first film, commissioned in 1968, it appears that Lamorisse worked freely. But the postscript, or second film, was edited together from footage captured in an attempt to satisfy the film’s commissioner, the Shah of Iran and his propaganda campaign. The difference between the two is marked by the way that the atmosphere of the second part or Postscript feels hostile, aggressive, and calculated in contrast to the warm and imaginative first film. It was during the making of this second film, I learn from Maziar Afrassiabi’s exhibition text, that Lamorisse, only 48 at the time, died in a helicopter crash. Thus, all of the editing was carried out after his death by his wife, Claude Jeanne Marie Duparc, and was said to have been done in such a way as to protest the Shah’s project. Knowing that the filmmaker—and his crew—died when their helicopter got tangled in metal cables above the massive Amir Kabir Dam in Iran during the filming of the second part of Le vent dex amoureux offers something for those who find meaning in tragedy. The film camera, as you may have surmised, was later recovered from the riverbed.

The death of an artist, especially during the creation of a work, presents a tragic ideal, a painfully magnetic and unsettling narrative. I ask myself why we are drawn to these stories. Is it because the artist died in the midst of creating something and that the creation/destruction paradox satisfies a deep need of self- and artistic- affirmation? Is it mythmaking, a defeatist romantic narrative about the death of the artist and some kind of appealing fatalism? I ask myself if I feel the same way about the death of the helicopter pilot, and I am not sure. I ask why, when the body has already been recovered, is it still so important to find the plane?

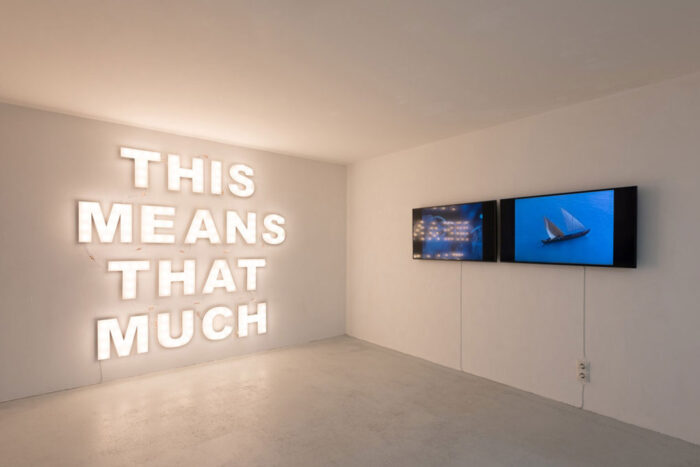

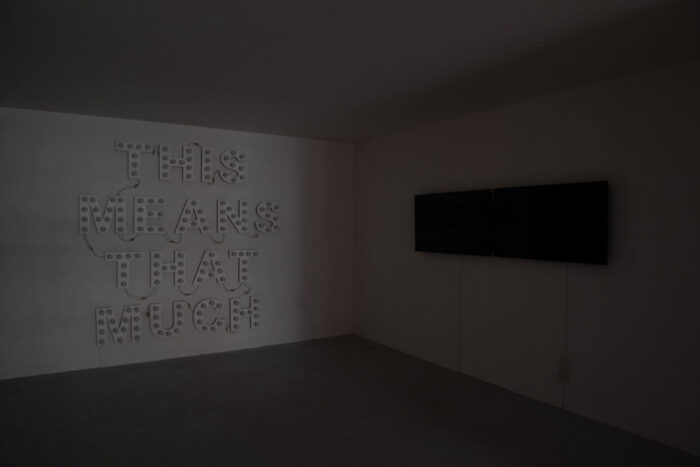

Marije de Wit’s work converses with similarly ambiguous equivalencies in This Means That Much (2021), a self-referential sculpture comprised of large painted words made of wood, multiplex and light bulbs. We encounter four words in English at the far end of the gallery. When the power is on, they’re brightly lit like an old-fashioned film marquee, claiming space and attention, and posing questions more than making statements, speaking directly to the two films by Lamorisse, standing in the background of Matthew Kneebone’s work Power Relations (2021), part of which features a custom-built LED display of blackout-related headlines in California. This means that much. Mentally filling in the blanks: This drought means that blackout. This compromise means that misfortune. This light here means that darkness there.

The rolling blackout, an entity in itself in The Last Terminal, is a direct result of the drought in California. The state relies heavily on hydroelectric power, and without enough water pressure to turn the turbine blades, hydroelectric generators fall short of the demand. When it is especially hot and dry, energy providers across the state turn off the grid to prevent the metal cables from sparking wildfires, which they have done in the past. Or, as in Traditional Chinese Medicine theory, the five elements can generate, control, or destroy each other: water controls fire, fire controls metal, metal controls wood, wood controls earth, and earth in turn controls water.

In this cycle, I have always missed wind.

Matthew Kneebone’s multi-layered work Power Relations intervenes within the infrastructure of Rib to activate a different energetic reliance. He makes the art space’s electricity source directly dependent on the energy available in California, a state—and condition—of the rolling blackout. This intervention within the space forces a reckoning with that which is unpredictable and beyond personal control. The exhibition—or life, rather—can end at any time. Taking place in real time, we might notice then how the slight breeze of the Baade Sabaa, the lover’s wind, has just left the frame of Lamorisse’s film. The lover’s wind maneuvers, it conveys messages from one work to another, stops to breath softly amongst the artworks, invites new actors into its dramaturgy, and openly converses with worlds on the other side of the gallery’s walls.

This wind weaves through Olivier Goethals Spatial Intervention (2021), a skeletal wooden architectural intervention in the center of Rib, so well suited to the space that it seems to have always been there. With its fluid functionality, it serves as a music rehearsal space for Rib’s staff band, accommodates artworks, documents, and ephemera, and provides a place to set down a cup of tea during a visit. Within that literal framework, you can steal a moment to read, study, or play a game of La Conquête du Monde (The Conquest of the World), the original board game made by Lamorisse, later renamed “Risk”.

The wind moves freely, blowing softly to the front door, close to where Eléonore Pano-Zavaroni’s work Afspraak Future (2021) has landed, or fallen, in a space of ongoing conversation and exchange amongst artists. This work evades easy capture, comprised as it is of personal artifacts, stories, and tangible objects that have surfaced through conversation and friendship. As such, the lover’s wind entangles itself throughout disparate geographies and personal relations as though it were tracing a thin blue line through the air— from the Amir Kabir Dam in Iran, to Folsom Lake in California, and back to Rotterdam’s windy port.

For the wind, equivalence is never the point. Wind only exists at all because on this unevenly heated planet, climactic differences generate atmospheric changes that become wind. There’s no wind without atmosphere.

The figures in Shahin Afrassiabi’s paintings appear to be in a distant, still, windless space. And yet, they evoke an atmosphere, they communicate some kind of movement, and there is a light source. As if made in a studio on the moon, these paintings offer a view to an unusual realm that has dimension, but where familiar, earthbound laws of physics do not make sense. Recall Albert Lamorisse’s early and most well-known film, The Red Balloon, where a young boy devotedly follows around a mysterious red balloon, a silent pocket of air, a voiceless actor suspended within the space of a shiny, taut, red film. The red balloon is not unlike the spheres in Afrassiabi’s paintings that seem to cradle an animate energy within. These spheres, full and taut, are teasingly perfect, even divinely spherical for those of us who are seduced by surface. And what would happen if they were to deflate, to lose the breath inside?

Shahin Afrassiabi’s paintings, the works that initially drew me to visit The Last Terminal, let me feel weight and form without gravity, shadow and texture without apparent cause. Since I visited, two of the paintings have been replaced with others, an event demonstrating a curatorial commitment to the idea of the rejuvenation of artworks in the ongoing and evolving exhibition. And then, in Three Yellow Orbs (2019), perhaps because it’s not expected, a glorious, lemon-buttery, yellow emerges from behind layers of darkness. And it’s mesmerizing how this color makes you want to wrap your hands around it, caress it, bring it close to your face to inhale its vitality—to love it, and deeply.

The lover’s wind in Hafez’ poetry, as I have learned, is a communicative wind that plays a number of roles: it conveys messages, it is the message itself, it receives messages, and it shapes meaning in the mind of the receiver. From one room to the next, from one painting to the next, from one landscape to the next: all of this happens in stretched out breezy shifts, long transitions from here to there, from this to that.

So this is how the wind shapes meaning in the heart and mind of the receiver, isn’t it? It never returns to its origins. The lover’s wind makes stories out of disparate events, geographies, practices, and people, and we merely sense it as a temperature change on the surface of our skin, that warm air felt on the upper lip as breath escapes. Making meaning out of an art practice—or an exhibition practice—or any practice, really—means doing all of these things, meaning-making-loving, returning to the breath, returning to life, returning and continuing to ask what there actually is—fundamentally—to return to, when breath, life, love, are not things to be had.

In the end, if there is an end, it doesn’t matter what gets recovered—the body, the plane, or the camera. Even with a deeply held sense of futility, it’s almost impossible to escape the compulsion of meaning making because things, undaunted, eventually rise to the surface.

Marianna Maruyama, 2022

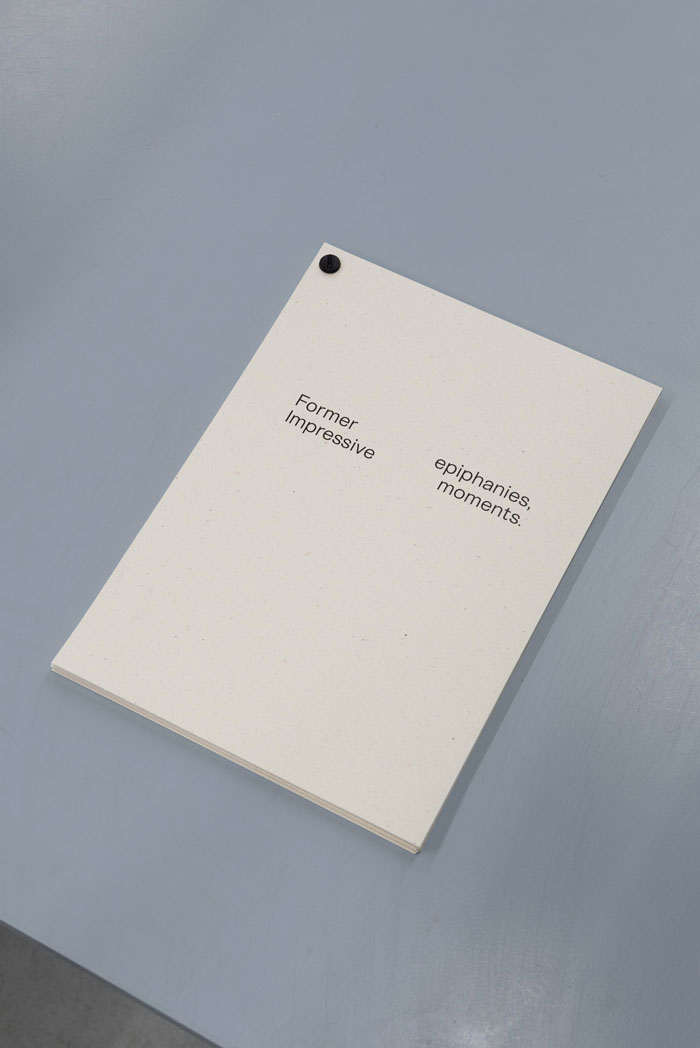

An Open Lexicon of The Last Terminal

A stream of words originating in the southwest corner of Rib, traveling to the front entrance in the northeast and past the door all the way out west.

Apnea: without wind; a suspension of breath; from the greek, ‘apnoos’ without breathing.

Baade Sabaa: The Lover’s Wind, the title of the documentary film by the late French director Albert Lamorisse; “a breeze that blows at sunrise from the east; a breeze to which lovers confide their secrets”; has many communicative roles in Hafez’ poetry: “an informed source; a sender giving information; it conveys the message; as a channel, it transmits concepts and messages; it is sometimes a harbinger; it receives messages; it shapes meaning in the mind of the receiver.” (Ali Asghar Kia & Saeed Saghe’i)

Compromise: compromise (com) With + (promittere) to release, let go, send, throw; also to foretell, assure beforehand, promise.

Dam: a hydroelectric energy source reliant on water pressure to turn turbine fans and generate electricity; a barrier; a disruption in flow; a shaper of water and land.

Endure: both to end and to outlast suffering; “the possibility of ending and the question of to what purpose must one endure?” (Maziar Afrassiabi)

Future wind: the name of one of the two companies that built the Haliade-X wind turbine in Rotterdam, the largest and most powerful turbine in the world, situated on the Maasvlakte (the reclaimed land flats of the River Maas); likely named after the Haliae.

Gravity: the unique atmospheric condition on Earth that permits all things to fall; lets carpets land; perceived heaviness and weight; significance; the etymology of grief shares the root of weight (gwere) with gravity, both are heavy.

Hafez: Persian lyric poet (born circa 1315 – d.1390). “Most of his poems are in the form of a ghazal (resembling the sonnet) and mostly dealing with love.” (Ali Asghar Kia & Saeed Saghe’i)

Haliae: the Greek/Roman sea nymphs who rode on the backs of fishtailed horses (hippomapoi) and dolphins; note the Haliade X turbine is named after a feminine source of energy.

Premonition: strong feeling of something (usually bad) that is about to happen; a sense of the future as a forewarning.

Risk: to run into danger; to venture; also the name of the popular board game invented by filmmaker Albert Lamorisse in 1957, first as La Conquête du Monde. In a telling name change, the game was rebranded as “Risk” after it was bought by an American company.

Seafloor Systems: the name of a company located on Commodity Way in Shingle Springs, California, offering survey solutions “from hydrographers, for hydrographers”; the company that surveyed Folsom Lake in search of the 1965 crash wreckage. (seafloorsystems.com/about)

Suspension: the condition of not being allowed to fall or end: the suspended helicopter, the suspension of disbelief, the suspension of energy leading to a blackout; suspension of pigment within a painting medium.

Venture: to go forth into the unknown; to dare; though the etymology is dubious—to vent, to blow, to risk.