The Archaeological Turn

Filmmaker Maeve Brennan on uncovering and preserving traces of histories that continue to haunt the present

Through processes of spatial and temporal layering, as well as connecting overlooked natural phenomena, marginal historical events, and individual life experiences, Maeve Brennan constructs compelling narratives that shed an unusual light on urgent issues of the contemporary world. Although never being directly addressed, scenarios of vast magnitude related to war, colonialism, and ecological crisis surface in her works, becoming the background on which those narratives unfold. Maeve Brennan recently took part to DEMO – Deptford Moving Image Festival and in 2018 was awarded the Jerwood/FVU Award.

Felice Moramarco: Your artistic research often focuses on elements that at a first glance look very specific and disconnected one from the other, then one slowly realizes that there is a very big and complex scenario emerging from the background, which is never directly addressed. Would you define this as your research method, or rather, as your poetics?

Maeve Brennan: Forging connections is at the centre of my practice; it is a part of my method but is also key in producing a poetics. I often begin with subjects that are seemingly unrelated—joyriding and archaeology in The Drift (2017) or bats, wind turbines and geology in Listening in the Dark (2018). Through a sustained engagement with a place I start to draw connections from one to the other, mostly led by personal encounters with people or places along the way. I see this approach as a way of accommodating the unexpected, it allows the films to take on unforeseen moments. I think the poetic moments in my research and filmmaking often occur within those unexpected encounters. In this way, I think the films also gain a proximity to reality. There was a beautiful text by Erika Balsom in e-flux some time ago, The Reality-Based Community, that described this kind of documentary approach. She says “The appearances of the world need our care more than our suspicion… Giving primacy to the registration of a physical reality can… reawaken our attention to the textures of a world that really does exist and which we inhabit together.” I think this kind of approach is key in a political climate that is increasingly divided.

The Drift (2017), 51 minutes, HD video with sound (video still) Produced by Chisenhale Gallery, London and Spike Island, Bristol. Commissioned by Chisenhale Gallery; Spike Island; The Whitworth, The University of Manchester; and Lismore Castle Arts, Lismore.

The construction of the narrative through personal encounters is indeed very evident in one of the films you just mentioned, The Drift. Can you tell us about how you built your relationship with the characters of the film?

I lived in Beirut for three years before making The Drift (2017) and during that time I met Hashem, one of the main protagonists in the film. He works at the American University in Beirut in a small basement office, piecing together fragments of Roman pottery that were excavated in downtown Beirut after the civil war ended. There is an overwhelming amount of material and Hashem, who is self-taught, has been carrying out these reconstructions for the last 25 years. The film documents his work, alongside other forms of maintenance and repair. We also meet the guardian of the Roman temples of Niha, Fakhry, who has worked in both the reconstruction and the protection of these temples for 43 years, taking over the role from his father. Then there is Mohammad, a young joyrider and mechanic who searches scrap yards to transform his BMW. He is from Britel in the Beqaa Valley, a town known for its car parts as well as its notorious ‘outlaws’ road’, a route across the mountains that leads directly to Syria and that, since the war began in 2011, has been used to smuggle Syrian artefacts into Lebanon.

These three lives intertwine, forging unlikely connections between car parts, stolen artefacts and ancient pottery fragments, always with a focus on acts of care and repair.

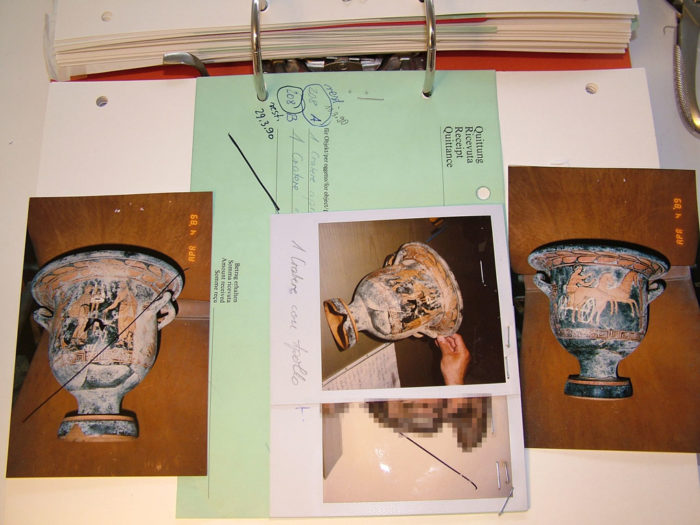

The Goods (2018), series of six billboards (332 x 300cm) Produced in collaboration with forensic archaeologist, Dr Christos Tsirogiannis. Commissioned by Kunsthaus Bregenz, Austria for KUB Billboards 2018. Photo by Markus Tretter.

The Goods (2018), series of six billboards (332 x 300cm) Produced in collaboration with forensic archaeologist, Dr Christos Tsirogiannis. Commissioned by Kunsthaus Bregenz, Austria for KUB Billboards 2018. Photo by Markus Tretter.

And the context in which the narrative of the film unfolds is the legacy of the Lebanese civil war. How did you deal with such a problematic context?

Although the film rarely addresses the civil war directly, it has of course shaped the lives of the characters, the objects and sites that appear in the film. Fakhry refers to his time guarding the temple throughout the war, spending day and night there to protect the sites from looting and theft. The civil war is physically present in the temple of Hosn Niha which was bombed and severely damaged when the site was used as a Syrian stronghold in 1978-80. Fakhry tells us that he knows where every scattered stone belongs.

The Drift is populated by men engaging in acts of care, with objects or sites that they have become intrinsically connected to. Through the film’s focus on repair, I tried to provide an alternative image to those that are pervasive in the media, dominated by conflict, violence and binary representations.

Jerusalem Pink (2015), 41 minutes, HD video with sound (video still). Produced by The Lebanese Association for Plastic Arts, Ashkal Alwan for Video Works 2015 and supported by Robert A. Matta.

The smuggling of ancient artefacts is also central to your last project, The Goods. Notably, starting from two looted Greek vases exhibited at Frieze Masters in London, you ended up looking into a huge system of antiquities smuggling. How has this project developed?

The Goods (2018–present) is an ongoing project that focuses on the illicit antiquities trade, tracing the underground networks that facilitate the looting, smuggling and selling of cultural heritage. When producing The Drift in Lebanon, I interviewed a number of antiquities smugglers and dealers and I became interested in the prevalence of looting and the underground economy more broadly. When artefacts are looted they are violently extracted from their archaeological context and a piece of history is erased. I asked one dealer where all these artefacts go when they leave Lebanon and he told me “mostly museums in London!’ So I became interested in the demand for these objects, which is ultimately what encourages and sustains the looting.

Soon after I came across the Frieze Masters case, in which two Greek lekythoi (vases) for sale at the fair were identified as illicit by Dr Christos Tsirogiannis, a forensic archaeologist. Tsirogiannis has access to a secret digital archive containing images of 100,000 stolen and looted artefacts which he uses to identify objects of potentially illicit origin in auction houses, galleries and museums. These artefacts are often seized and repatriated to their country of origin as a result of his work.

The Goods is a collaborative project with Tsirogiannis, in which we will attempt to make visible a largely invisible economy that continues to involve major institutions. This is essential in a moment when there are increasing concerns around the repatriation of cultural heritage, as nations come to reflect on their museums and collections in relation to imperial and colonial histories. I see Tsirogiannis’ work as a form of repair, following the damage done by colonial powers in stealing, exporting and “preserving” the cultural heritage of the Mediterranean, Middle East, Africa and Asia. I have just received the Stanley Picker Fellowship at Kingston University to develop this project over the coming year.

Listening in the Dark (2018), 43 minutes, HD video with surround sound (video still). Produced by Film and Video Umbrella. Commissioned for the Jerwood/FVU Awards 2018: Unintended Consequences, a collaboration between Jerwood Charitable Foundations and Film and Video Umbrella.

Another very complex and urgent issue is the one you tackle in Listening in the Dark, that is, the devastating impact that humans have on the ecosystem, the Anthropocene. Also in this case, you hint to such a vast and complex scenario through elements that could be considered quite marginal, compared to the magnitude of this phenomenon.

The film’s starting point was a very small explosion. I read an article that described the discovery of dead bats at the foot of wind turbines but they did not show any signs of collision. It was later discovered that when the bats fly into a pressure drop behind the turbine’s moving blade their lungs explode. I found this intriguing; wind turbines are necessary in a move away from fossil fuels in order to protect our ecosystems and yet they were having this unforeseen impact on bats (a protected species in the UK). From this point of encounter between animal and machine we can start to grapple with the complexities of the ecosystem and how any human incursion will encompass many unknown effects.

I was also interested in decentring the narrative around the Anthropocene. Looking to Haraway’s idea of the “Chthulucene” and “more than human worlds” I decided to place the bat at the film’s centre. Although bats are mammals like us they are radically different (see Thomas Nagel’s essay What is it like to be a bat? which ponders bat consciousness). Most significantly they use their ears to “see” using a process called echolocation. They are also a species we know relatively little about as they are notoriously difficult to study due to their nocturnal habits, small size and ability to fly. In the film they become analogous with the unknown, they remind us of the vast and incomprehensible complexities of the ecosystem we exist within and how scientific discovery continues to reshape our understanding.

In the film we observe the patient work of chiropterologists (bat experts), collecting and accruing small pieces of data on bats, sometimes only catching one or two in an entire night’s survey. In the current context of climate crisis, it is vital to reconsider our position in relation the environment and I see this patient and meticulous work as a model to look to as a form of engagement that does not attempt to dominate its subject but instead asks us to observe and listen.

I think the film incorporates the magnitude you mention in your question through its handling of time. The film is structured around three timescales. First, the vast scope of geological time provides the physical grounding for the film in the landscape of Scotland. Second, evolutionary time with reference to the appearance of bats in the fossil record 50 million years ago. Third, the most recent period of human technological advancement and its disproportionate effects. Moving across and between these three ‘times’ allows the film to tackle the complexities of the Anthropocene, all the while reminding us of the comparatively insignificant period that humans have formed a part of the eco-system.

Listening in the Dark (2018), 43 minutes, HD video with surround sound (video still). Produced by Film and Video Umbrella.Commissioned for the Jerwood/FVU Awards 2018: Unintended Consequences, a collaboration between Jerwood Charitable Foundations and Film and Video Umbrella.

Interestingly, this kind of archaeological approach clearly informs all your works. Agamben once wrote that archaeology is not just about recollecting historical facts, but also looking for not yet expressed possibilities than could be unfolded in the future. Is your interest in archaeology animated by a similar tension towards the future?

Although there is a recurrent interest in history throughout my practice, it is always incorporated to frame or rethink the present moment. For Jerusalem Pink (2015), I went to Jerusalem and the West Bank to research my great-grandfather, Ernest Tatham Richmond. He was an architect and was invited by the British Mandate government to provide an architectural survey of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, where he then lived from 1917-37. This survey became the basis of the film which goes on to investigate the significance of stone in contemporary Palestine through interviews with an archaeologist, a geologist, a stone worker and an architect. The survey itself is a historical document, published in 1924 it contains detailed descriptions of the building’s state of disrepair. In the introduction I came across a quote describing the fourteen centuries of maintenance and repair that the building has undergone—“The Dome of the Rock is alive—almost in the same sense that a man is alive. It changes its tissues and it renews its structure in order to maintain power to enshrine the soul that is in it.” The building’s survival is evidence of a continued human determination and belief in what the building represents for Palestinians. This is not only a historical issue but is central to the ongoing conflict in Jerusalem and when I came to film the interior of the building, the dome was being restored.

I always think of a quote by Hartmut Bitomsky on Peter Nestler’s films: “Finden, Zeigen, Halten (finding, showing, holding): like an archaeologist patiently and meticulously digging into the soil of material life, uncovering and preserving traces of histories that continue to haunt the present.”