The Abyssal Horizon

Space, silence, gesture in the prefigurative atlas of “The Last Lamentation”

Through the project The Last Lamentation, artist Valentina Medda explores the tradition of Mediterranean ritual mourning, by placing it right at the center of contemporary thinking.

Presented for the first time on the occasion of Art City Bologna, in the Sala delle Catacombe at the Cimitero Monumentale della Certosa, in collaboration with Museo del Risorgimento, MAMbo – Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna and NOS Visual Arts Production, the work was realized thanks to the support of the Italian Council (XI edition, 2022), and will become part of MAMbo’s permanent collection.

“For beauty is nothing but the beginning of terror.”—Rilke, Duino Elegies I, 1912

“At last, when the ship drew near to the outskirts, as it were, of the Equatorial fishing grounds, and in the deep darkness that goes before the dawn, was sailing by a cluster of rocky islets; the watch—then headed by Flask—was startled by a cry so plaintively wild and unearthly—like half-articulated wailings of all the ghosts of all Herod’s murdered Innocents—that one and all, they started from their reveries, and for the space of some moments stood, or sat, or leaned all transfixedly listening, like the carved Roman slave, while that wild cry remained within hearing. The Christian or civilized part of the crew said it was mermaids, and shuddered; but the pagan harpooners remained unappalled. Yet the grey Manxman—the oldest mariner of all—declared that the wild thrilling sounds that were heard, were the voices of newly drowned men in the sea.”—Herman Melville, Moby Dick, 1851

I initially encountered Valentina Medda’s work in January 2020, during that year’s edition of Art City, Bologna, Italy. The artist had just returned from Lebanon and was developing what was to become The Last Lamentation. She was exhibiting a scaled down version, comprised of small models, sketches and her dreams/wishes at the Alchemilla Space, Bologna Italy. I met her and followed her along many different paths I’m about to recount here like a journey.

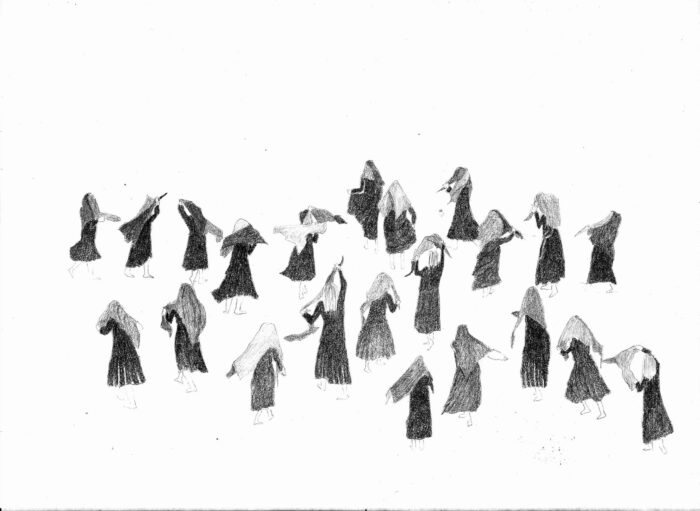

These initial steps would trace something like a circuitous warp as she weaved knots of research around her homeland, Sardinia, bridging an ancient desire to thus reconnect it with the Mediterranean sea as a whole. An umbilical pull seemed to plunge the artist’s own body down into the deepest and most impenetrable part of the island, geographically and culturally, tracing and spinning the wefts of a concretely abstract and materially ciphered, obscure, magical and geometric horizon. This in turn evoked the shapes of a millenary enduring traditional mourning garb which then enfolds and sculpts female bodies in an austere, silent and sepulchral severity, vitalized by ancient things.

Backwards and against the tide

Like a sea current, The Last Lamentation was in fact born out of ripples—and from its own becoming wave, sea, fluid—between the two coasts of the Mediterranean, East and West, and metaphorically between the South, global and geographic, and a cartographic center, albeit still a minor and isolated one. Sardinia, an (is)land that embodies an ambiguous relationship with the global North, the colonizer countries, Europe and the Atlantic sphere. From those coasts, themselves colonized, surveillance radars observe, control, monitor arrivals, departures, landings. Along those coasts, armies experiment with new forms of weaponry, killing the sea.

The route traced by the project, even in these embryonic stages, followed ancient migrations, the founding of cities and colonies, examining both the history and the present of the Mediterranean and the culture that persists on its shores.

It initially originated in Beirut in 2019, entitled A Collective Mourning—thanks to a residency awarded to the artist, in collaboration with the Beirut Art Residency. On this occasion, Medda explored the relationship with the sea, the bond between body and border, the coastline skin to land on the breakwaters of a territory that appears impenetrable, reinforced by concrete, as she is forced to observe from a distance, beyond its sea barriers.

Here the artist chartered the direction of her research, inscribing and determining the desire to deepen a relationship with the marine horizon, a horizon not equally accessible to all bodies, unreachable for some. The sea as a physical, hard, solid frontier and at the same time a fluid, multi-species environment. The sea that opens up to questions embodied during the work’s evolution.

The sea is the question.

The initial concept ink sketches, illustrations, photos and a short video that remain all constitute the basis for a new study of The Last Lamentation and future research. From the East then, this first sound is activated which will reverberate like an echo, a sinister resonance, throughout a body of water, all the way to Sardinia. Sound waves refract and mix on sea waves. Vibrating bodies, resonating bodies, oscillating movements.

How places relate is distinctive and not to be taken for granted

Lebanon is a privileged place to observe the Mediterranean, drawing on an ancient and profound history of relations with Sardinia, of sea-routes, navigation and cultural exchanges. From here the Phoenicians, of Canaanite origin who lived in a strip of land close to the coast stretching from Amrit and Arwad to Gaza, developed their capillary influence around the Mediterranean in the first millennium BCE. (…) In Sardinia, they founded settlements that were trading outposts at different times from pre-colonisation to colonization during the Iron Age. Towards the end of the 9th century BCE, they intersected with the late aspects of the Nuragic culture there, giving rise in some cases to significant exchanges and cultural influence (…) founding the main cities on the southern coast of the island, such as Karalis, Nora, Bithia and Sulki.

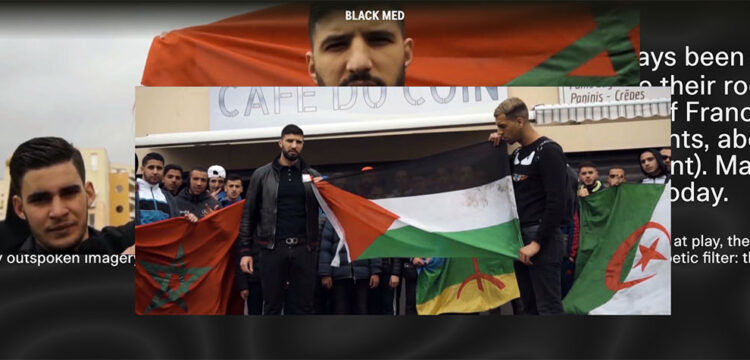

Phoenician occupation and colonization raises questions today concerning how cultural exchanges and influences are established, transmitted and recognised and how modern history narrates them in a rather roundabout way, amalgamating western culture into one block, with no nuances, boundaries, or questions. This approach, as Predrag Matvejević points out, challenges how, each time, the rhetoric concerning the Mediterranean itself has “served for democracy and demagogy, liberty and tyranny. Its effects have occupied the forum and the temple, justice and the sermon. The Mediterranean and the discourse on the Mediterranean” Matvejević concludes,“are inseparable from each other.” Colonisations that look towards new colonisations. To the forms of the Mediterranean massacre, to the violence of that Black Mediterranean whose bodies and borders we see burning today.

The burning metaphor is not accidental. As Prof. Alessandra Di Maio noted that “(…)The metaphor of ‘burning’, in the sense of ‘crossing’ the sea, is used in colloquial Arabic by North Africans to refer to those who, since the early 1980s, have crossed the Mediterranean en masse in the hope of finding work, democracy and better living conditions for themselves and their families on European shores. Besides its literal meaning, the Arabic verb haraqa (to burn) is used in Mediterranean Africa, from Morocco to Egypt, in a number of colloquial expressions that always imply a transgressive experience. In the Arabic language, when one ‘burns’ a rule, a law or even a red light at an intersection, one is in fact disregarding a directive, transgressing a norm or breaking the law. Likewise, the Harragas (literally ‘those who burn’, i.e. migrants crossing the sea) are aware that harg, i.e. ‘burning’, or crossing, the Mediterranean, corresponds to an act of transgression.” In fact, etymologically to transgress signifies to “go beyond”. To pass beyond, to come apart, to burn elsewhere.

Displacement

“An echoing space, mysterious and distant.”—David Toop

The Last Lamentation is traced through the cipher of distance and the continuous displacement of gaze and geography, together with the artist’s practice requiring slow approaches, apparently disorganized movements, with progressive and retrograde phases. An evolution that becomes a stylistic feature and outcome in the video work and in the performance. These are flights, like those characterized by the unfolding of “winged” figures silhouetted against the blue in the work’s last version, where the body and gaze draw nearer to a body that is itself a geography, to find the forms of a situated spatiality and of a perceptive quality that resonates with the complexity of the present.

2022–2024

The work in the artist’s words is a funeral rite for the Mediterranean, conceived here as a place of waiting, suspension, death, the embodiment of an absence, a deposit of bodies and the body itself. The work portrays the tragedy of the sea through a hypnotic vocal and choreographic score that rewrites ritual codes in abstract, contemporary forms.

The project goes through various evolutions between 2022 and 2024, also thanks to one of Italy’s highest cultural recognitions: the Italian Council XI Edition funding award for the production and international promotion of the work. A new journey begins by delving deep into Sardinia’s inner province of Barbagia, in Nuoro, a scarcely anthropized territory which to some degree is equidistant from the Italian mainland and continental parts of Europe, as from the African coasts. An area where autonomist urges for independence have determined a cultural awareness and a form of collective critical consciousness, through systems of self-managed transmission among the younger generations. A context however, that for several decades has been experiencing the threat of depopulation as young adults gradually abandoned the countryside and mountains, added to a low birth rate, an ageing population albeit hailed a land of centenarians.

A cradle of millennia-old traditions, all distinctive in their minutiae, preserved like cameos, with a vivid cultural plurality and richness, rigorously guarded despite the passage of time. A song—birth songs, those of struggle, work, as well as mourning songs—is a powerful instrument for collectivizing sorrow and joy, of civic sentiments, as well as intimate ones. So too is textile art. Both aspects become the artist’s own legacy to reflect on during her work.

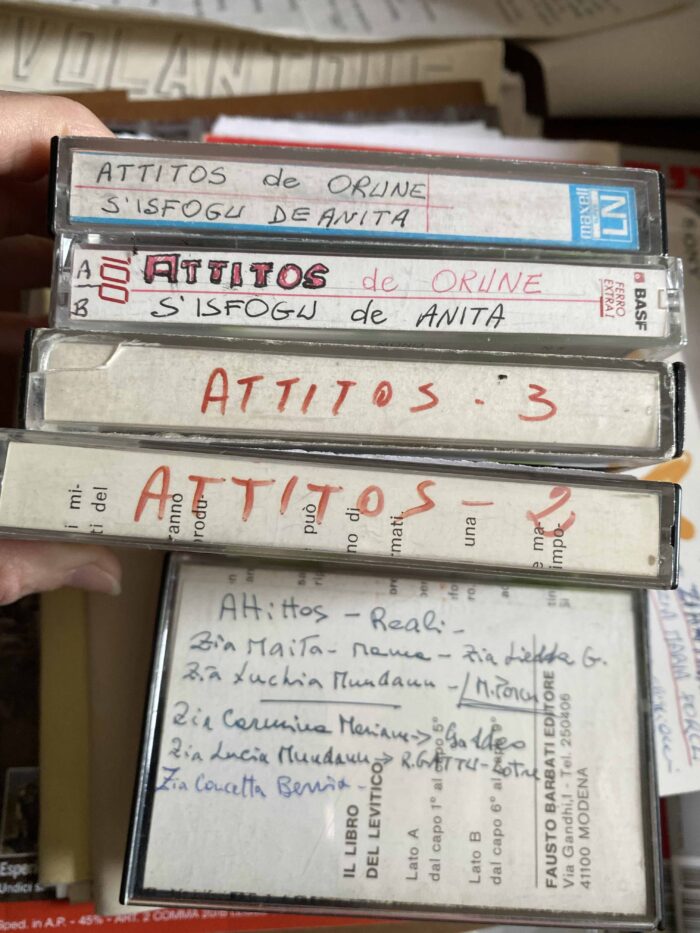

Medda travels in fact through sources using bibliographic research and direct experience, salvaging memories, examining archives, official ones, which were virtually non-existent at least in the main research centers in Sardinia that were consulted along with “living” sources. Kinships, relationships, dialogues, listening processes, networks that re-radiate into new networks, intuitively following building/revealing/opening a sprawling web.

The residency, realized in collaboration with MAN Museum (Nuoro) and Sardegna Teatro facilitated significant contacts with spaces and contexts of lamentations around Sardinia: Orune, Orgosolo, Oliena, Nuoro, and then in a roundabout way to Posada, where the artist visited the son of a Prefic, professional mourner, from Orune, Giovanni Zidda, a teacher, Anthropology graduate and author. Here, Medda listened to various recordings of laments by Zidda’s mother, one of the last local official mourners, with a fellow villager (originally from Calabria, now living nearby) reenacting the pain of the premature loss of her husband. These laments combine different traditions, recounting violent deaths and feuds, breaking through the silence around “endings”. These recorded narratives let us listen to this oral poetry, with repeated choruses, defined scores, confirming De Martino’s anthropological description of its structure. (…)

Revocations of death, invocations, invitations to remembrance, ways of celebrating, epithets are interspersed with moments of forgetting and hiatus, inaudible cries, a female domain where this act of singing a particular grief expresses a greater pain: the pain of a gender, and with it the pain of fear, because for women, for the feminine sphere, fear can correlate with a form of pain: fear of loss, of culturally disappearing, of the crisis of presence, reason itself, social violence. Fear of crossing the line and passing into that mid realm of madness, of absence. Between life and death, between being and non-being. Fear and pain, individual and collective, reside in these wailings and the courage to sing them.

On this journey the songs connect the places and reveal the faces, landscapes, silences. The sounds between the houses, the church bells, the shadows in the streets, the aural and visual spectrality, become an exercise of imagination, in capturing, in divination. A demonological perspective opens up the possibility of a different epistemology, as if a yet further form of awareness could possibly be activated in this relationship with the landscape and its abandonment, with echoes, with the monstrous, the unspeakable, the perturbing. [1 ] And as though this awareness sets the whole dialectic free to become the awareness and understanding of limits. Medda explores this possibility with the practices and mediation of listening, with the pause in transition, sedimenting the instruments of knowledge and above all placing the body first of all, in a clinamen.

The female figures across the villages and crossing the various sites are silhouetted in the sharp, cold February light with their black, chiseled profiles like in the Sardinian artist Giuseppe Biasi’s early 20th-century engravings, imprinting themselves on both gaze and collective imaginary. The countenance of the land emerges by subtraction. A backlit-body makes it stand out; the shape of the landscape in negative image and as landscape itself. The spaces between the shawls, between the clear-cut geometries, the shoes with their small and timeless heels leaving a dull percussive timbre through the alleys allow the flavor of time’s stillness emerge, of a time that has already disappeared, yet is present, reappearing in its unsettling form as a ghost. An echo. A shadow. A whisper. Even here in the landscapes, unexpectedly dangerous.

There were valuable encounters in Orgosolo with the Prioresses, a women’s confraternity dedicated to preserving the Church’s worship of the Rosary, as choir of the Sardinian liturgical and paraliturgical tradition. Controversially, they are also custodians of traditional ritual lamentation, deemed pre-Christian, thus not officially recognised for official Church funeral rites. An historical perspective opens up as they recall the transition from the 1980s to the present day, from the period of feuds to the last lamentations. They disclose how their sons were murdered, about the art of knowing how to cry and after initially refusing, they slowly, slowly opened up to reveal their skills, in how to embody their total commitment, opening themselves up to pain, with wailing in their voices and the beating of their bodies.

Medda takes the voices, sounds and landscapes conceptually back to the sea, relocating and handing them over to a new territory, together with the memory, faces, eyes and recorded testimonies from the months of research to a group of women active in the province of Cagliari. After the inland Barbagia research, she convenes a participatory process closer to the coast over different periods across roughly three months. She invites Claudia Ciceroni, a vocal trainer, who then contributes to the work’s final sound composition. Medda rigorously researches specific conditions. Everything already seems etched in her mind when she reaches the theater; planted like visions, effigies that recall, condense, stitch together the traces, voices, gestures, memories absorbed from Lebanon to the Sardinian hinterland, to bring them back again to the Mediterranean.

(…)

The loss of presence here becomes the compelling prerequisite for embodying weeping, a weeping that exhausts, drains, establishing that dazed stupor that De Martino identified. An unproductive weeping that does not let the “world” reproduce itself and consequently is determined as socially dangerous. To be a lamenting mourner, as De Martino had already noted in his research, is in effect today a source of stigma, linked to such a radical ritual and ancestral practice that already in the post-war economic boom period people were dismissive of it. Even more so today given this global capitalist and productiveness acceleration. A body action, heartbreak, the end, mourning—action with no procreation. This is what makes it profoundly political. This does not make it any less fruitful: it is in fact an act of care, of bonding, of inter-species cohesion, of other kinship, beyond biological determinism.

Medda does not extract the exegetical pathos out of this movement, but rather whittles it out, to consolidate it in hermetic movements, measuring out that foundational presence/world relationship interspace, a distance, De Martino described that is regenerated “every time the threat of its dissolution looms, understood both as the ebb of its presence in the world, and as the intrusion/invasion of the world into the space of presence.”

Medda orients herself with the same methodological tools for her gestural score as she would for sound composition, which she had always planned would be, and would have always been about breathing. Breaths that become sobs, chorus, song, sound. Breaths that merge into one, breaths that are like the very sound of the sea: of the sea, of its body/totality and of all the bodies lying within.

A long wave from pneuma to breath, to the whole Mediterranean. Again.

David Toop’s words resonate sinister and exact: “Sound is absence, beguiling; out of sight, out of reach. What made the sound? Who is there? Sound is void, fear and wonder. Listening, as if to the dead, like a medium who deals only in history and what is lost, the ear attunes itself to distant signals, eavesdropping on ghosts and their chatter. Unable to write a solid history, the listener accedes to the slippage of time.”

Sound, ghosts, passages of time, a stumbling linearity, an origin’s indecipherability, the undertow, all appear in these bodies and in these haunted bodies. To be “singular” and flock at the same time, to be plural creatures, to be…

[1] Farnetti, L. SIL- Società delle Letterate. Conference 26 November 2023.

This text was translated by Maria Galante.

The Last Lamentantion‘s composition and production sound mixer is by Gaspare Sammartano and

composition and vocal training by Claudia Ciceroni.