Tehran, 1979–2019

The state of things in the capital of Iran, forty years after the Revolution and amidst the second wave of US sanctions

Beside the parallel calendar, exonerating from the social obligation of the New Year’s celebrations, Tehran’s best merit is that she does help discard quite a bit of that Western gaze we’re so drenched with, that tends to render the world outside of Europe without an agency. The attempt here is not to make Tehran appear as a city that’s worth visit, or alive enough to be labeled as a “contemporary craving city.” You all may want to hear that. Probably though, we might end up with a similar result because all I’ll be writing is nothing but a very personal love declaration to a city and to the people who inhabit her.

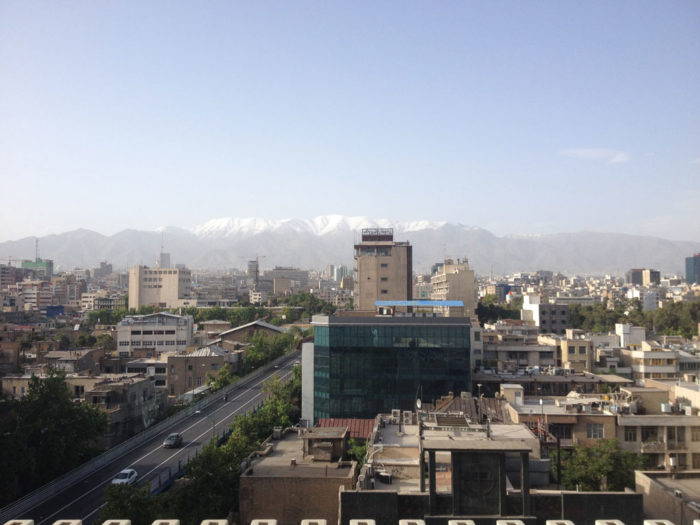

Tehran, April 2016

Mural, Tehran, January 2019. Photo Golrokh Nafisi

Tehran is not beautiful, or better to say, if you want to go sightseeing then land in Tehran and go to Esfhan, Yadz or Shiraz. If you want to see the past, Tehran is not the place where you can find it. In Tehran you find the most palpable contemporaneity. From a very exclusively advantage point of being in one of the few places in the world that witnessed a successful revolution, precisely 40 years ago (11 February 1979). I don’t know whether you have a thing for revolutions like I do, but successful revolutions are pretty rare. Also, as Professor Behrooz Ghamari-Tabrizi explains, the Iranian revolution was the one with the biggest participation in history. Only two per cent of the population took the streets during the French revolution; only 1,5% in the Russian. 10-15% of the Iranian population all over the country actively participated in protests and turmoils, most of which happened in Tehran. Before and during the revolution, Michel Foucault visited and wrote thoroughly about it. Generally speaking, the relationship between Tehran and contemporary History is emblematic.

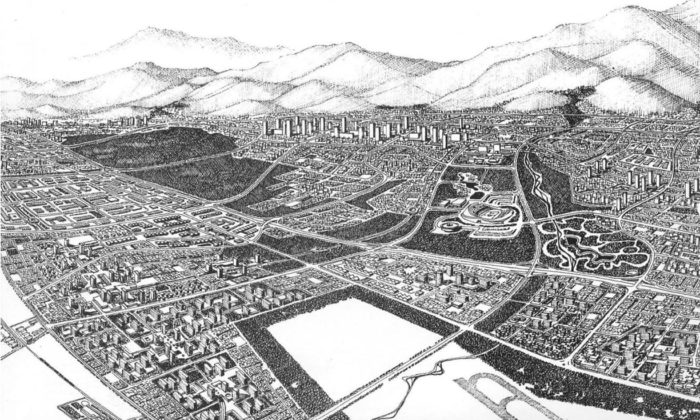

Victor Gruen’s 1966 masterplan for Tehran. Photograph Source: Tehran Municipality

My favorite description of the city of Tehran is Asef Bayat’s opening of his article Paradox City: “Tehran is not an ‘interesting’ city. It is not like its regional counterparts Istanbul or Cairo, with their long imperial or colonial histories, pivotal geo-political locations, memorable architecture, and natural charm. Tehran remains a provincial metropolis of some 12 million people, with streets choked by four million vehicles and air pollution that kills 3,600 inhabitants per month—factors contributing to a “livability” ranking that places it among the ten worst cities in the world, between Dakar and Karachi. But it is a city with extraordinary politics, rooted in a distinctive tension between what looks like a deep-seated ‘tradition’ and a wild modernity.” This essay was written in 2011, and by today greater Tehran is almost reaching 14 million inhabitants. Anyway, Bayat continues “in the West’s imagination, Tehran has principally been seen as a city of lofty minarets, piercing calls to prayer, bearded clerics, and women veiled head-to-toe; a city of mud bricks and narrow alleyways populated by extended families.” In fact The Guardian recently covered Tehran in its series The next 15 Mega Cities, with an article titled precisely Like LA with Minarets: how concrete and cars came to rule Tehran. Now, you can read the article if you want, and hold on to a very well rooted idea of the third world, where any place other than Europe or America needs to be rescued and made more similar to what we already know. It goes as usual complaining about pollution, warning to “watch out for cars” and being all worried about women being forced to wear a hijab. What I suggest to read instead is Alex Shams’s reply to this article, where you can get a better idea on how Tehran is really doing today. I agree with him when he says “the [Guardian] article recycles tropes that reduce metropolises across the Global South to the same stereotypical image: unruly and always on the brink of disaster. In an age where portrayals of the Middle East are so often mired in reductionist, Orientalist cliches, journalists have a responsibility to dig beneath the surface. It’s easy to write about what’s wrong; it’s harder to find the stories of those who succeed in the face of adversity. But those are the stories worth telling.” He goes on giving us a clearer idea on Tehran’s urban planning and freeway system—a very present feature in Tehran, a feature I am very attached to, as well as to her legion taxis, on which I personally believe I got the real experience and best view of the outdoor city (not a case that director Jafar Panahi chose to disguise himself as a taxi driver to shoot his docufiction in 2015). Shams examines also the expansion of social and cultural venues, which is really noticeable all over the centre of the city. When I say centre, I don’t mean downtown, because as many other places in the world Tehran has a clear distinction among her North, Centre and South parts, both in terms of wealth and consequently in terms of urbanism and architecture. So, the centre part of Tehran pullulates of cafes, libraries, museums, galleries and foundations, as Shams explains “undisturbed by morality police and often subsidized with public funds.”

Tehran 2011, Source: pbs.org

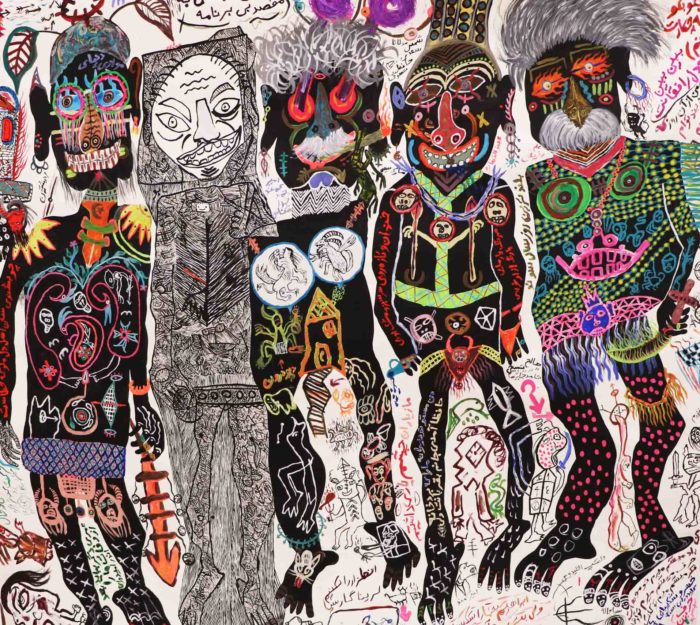

As mentioned in the same article, the second week of January 2019 has witnessed Tehran’s very first Art Week—following the modest Art Fair that has been going on since 2012—born from a collective effort among the local institutions in response to Trump’s second wave of sanctions and to Dubai’s monopoly in the region. Beside being completely free of charge, thanks to a greater network of volunteer passionate workers, TAW’s focus goes on the relationship between the citizens and their city, and the citizens and visual arts. Quoting from the TAW catalog’s opening essay by Sohrab Mahdavi “Tehran Art Week wants to join the city, citizens and art” meaning to reclaim the right to the city not only for “those with means” or for “transit.” I love that Mahdavi refers to the tautological relationship between the city and her citizens as fellowship, claiming that “should the number of those who want to use the city not for transit but for association increase, the quality of their affiliation will become an issue and enter their lived experience. Such citizens would transcend their frustration to formulate their vision of the city; find ears to hear and eyes to see among municipal officials, and convince them to abide by their demands. Such citizens wouldn’t seek comfort only in the quiet of their homes but roll up sleeves to create it everywhere.” Indeed, in a place like Tehran where the domestic dimension is so significant and comfortable, always open and prepared to host guests, this kind of statement is very meaningful. TAW included works commissioned for the city alongside those appearing in galleries, and an incredible amount of panel discussions, lectures and talks, happening simultaneously in different locations all across the city, all for free. Among other shows, I had the pleasure to see at Delgosha Gallery, the exhibition titled I Put a Spell on You, with beautiful paintings by self-taught painter Mohammad Ariyaei, in a mixture of Art Brut and wild expressionism, allusive poems by Saadi and Hafez inscribed on mysterious characters, all in extremely bright colors. If the paintings themselves weren’t exotic enough, from the gallery statement we learn that the artist grew up with his grandmother, who was an exorcist. Then another kind of darkness is recounted in the paintings by Majid Fathizadeh at Ab/Anbar, as compelling and beautiful.

Mohammad Ariyaei, Untitled, 2018. Courtesy Delgosha Gallery

A place where to witness the glorious encounter between revolutionary aesthetics and publishing was the Safavi Book Bazar, north of Tehran’s Enghelab Square (Revolution Square), which was chosen to display forty protest posters related to the revolution. Within its beautiful four stores passage, housing bookstores, book binding and printing workshop, the Bazar is best known as one of the main unofficial sources of archive material on graphic design and publishing history. The posters were perfectly integrated in the overwhelming environment, that from the top floor looked like a miniature vivant. I could have spent hours in there.

Safavi Grand Book Bazar and Tehran Art Week, curated by Aria Kasaei

Safavi Grand Book Bazar and Tehran Art Week, curated by Aria Kasaei

Safavi Grand Book Bazar and Tehran Art Week, curated by Aria Kasaei

Safavi Grand Book Bazar and Tehran Art Week, curated by Aria Kasaei

Anyway it feels like I missed more than I actually saw, so I won’t try to turn this report into a review. Nevertheless, any art event is in fact a parameter that tells us much more about its context. As a market like another, art is a measurement of wealth and culture, but it is the way art is done and for whom to tell about its intention. Going back to Mahdavi’s statement “ TAW can help with increasing the arts’ appeal to the public. The decision over the place of art in our lives cannot be left only to the museum directors, collectors, market speculator or gallerists; nor should financial measures dictate what type of art is important and should find a market. TAW can perhaps help reduce the gap that separates art from the city and its citizens, in this way make the city liveable, citizens inquisitive about their surrounding, and bring a public face to the arts” (source TAW catalog). Meaning that if there are gaps, Tehran and her citizens are actively busy in filling them.

Karim Khan Kand Boulevard, January 2017

Tehran, 2017

So, how is Tehran really doing? The way I experience Tehran each time is very specific. I see it through the gaze of people—mainly artists, that chose to live there, as opposed to the many who leave to study and work abroad. The Iranian is a diasporic population, both for political and professional reasons. As artist Golrokh Nafisi puts it, there is a difference between mosafer and mohajer, the traveller and the immigrant, and first of all in the way they narrate their stories. As mosafer they are fine with keeping their mother language, because eventually they will bring their stories home. As mohajer an effort is made to use the language of the country where one lands, because the story will be destined to that other geography. The people who introduced me to the city are mosafers. They speak the same language of the city and they are in constant dialogue with her, in constant negotiation with a mother that welcomes almost 14 million children. They are people who invest and engage with their surroundings, and take political stands through the adversities. In this particular moment they face economic sanctions, that are designed to oppress the middle-lower classes, in order to drive them to despair in hope for a repentine political turn. Their impact on everyday life is not always perceivable, but it is undeniable, as everyone’s mood and economy is obviously deeply affected.

Tehran freeway, January 2017

Imam Khomeini Airport, January 2019

Tehran hasn’t just witnessed a Revolution; after that there was war, and forty years of Islamic Republic. In 2009, there has been the Green Movement, which served as an example for the Arab spring in the entire region. When he speaks of the Iranian—or Islamic revolution Michel Foucault uses the expression “political spirituality:” he says “I do not feel comfortable speaking of Islamic government as an ‘idea’ or even as an ‘ideal.’ Rather, it impressed me as a form of ‘political will.’ It impressed me in its effort to politicize structures that are inseparably social and religious in response to current problems. It also impressed me in its attempt to open a spiritual dimension in politics.” Professor Behrooz Ghamari-Tabrizi tells on how Foucault had witnessed a “collective will” in the streets of Tehran, which in France would have just been an abstract political concept. This is the same image I have been exposed to since the first time I visited. Of course I didn’t witness a revolution myself, but somehow I felt it in a way it made me want to return. Foucault continues “With respect to this ‘political will,’ however, there are also two questions that concern me even more deeply. One bears on Iran and its peculiar destiny. At the dawn of history, Persia invented the state and conferred its models on Islam. Its administrators staffed the caliphate. But from this same Islam, it derived a religion that gave to its people infinite resources to resist state power. In this will for an ‘Islamic government,’ should one see a reconciliation, a contradiction, or the threshold of something new? The other question concerns this little corner of the earth whose land, both above and below the surface, has strategic importance at a global level. For the people who inhabit this land, what is the point of searching, even at the cost of their own lives, for this thing whose possibility we have forgotten since the Renaissance and the great crisis of Christianity, a political spirituality. I can already hear the French laughing, but I know that they are wrong.”

Foucault, Tehran Airport, September 1978 (screenshot of a talk by Professor Behrooz Ghamari-Tabrizi at Stanford University on May 3, 2018)

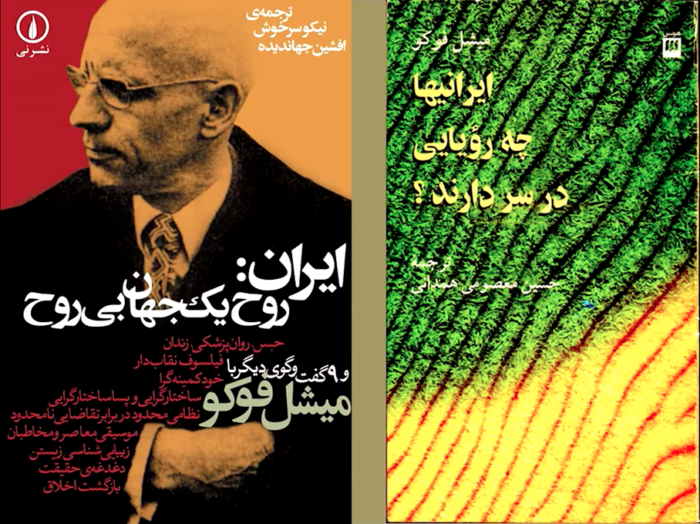

Right: Michel Foucault, What are the Iranians Dreaming About?. Left: Iran, The Spirit of a Spiritless World. Farsi Translations (screenshot of a talk by Professor Behrooz Ghamari-Tabrizi at Stanford University on May 3, 2018)

Beside seeing her mountains—the real ones and the rice ones—and her freeways, her taxis and murals, her bazaar and her avenues, when I think of Tehran I see all these nuances. I see all her ambiguities and possible histories, containing all the cities of the world at once. When I think of Tehran, I see a continuous city embodying all the contradictions of the contemporary world.