Sustaining a Weight

Speaking back to imposed formations of identity and otherness: a conversation with Holly Graham

On September 28th, If Body will present Sustaining a Weight, the first solo exhibition in Italy of artist Holly Graham, who previously resided at the British School at Rome between January and June 2023. Held at Lateral Roma from September 28th to October 15th, The exhibition will showcase a series of Graham’s new works that span between audio and text, sculptures, still and moving images.

The following conversation delves into the issues addressed by Graham’s research around how ideas of identity and otherness take form and are shaped over time, particularly in relation to the perception and understanding of blackness, ethnicity and race.

If Body is a public visual and performing arts program that focuses on the body as an artistic language and learning methodology based on experience and participation. Conceived and curated by Sara Alberani and Marta Federici (LOCALES), it presents new performances, talks, workshops and exhibitions that explore the cultural, social and political meanings associated with body and corporeality throughout six events. The first edition involves interventions by Amelie Aranguren (INLAND – Campo Adentro), Marie Moïse e Mackda Ghebremariam Tesfau’, Pauline Curnier Jardin & Feel Good Cooperative, Adelita Husni Bey and Holly Graham.

For this occasion, a series of interviews will be conducted by Chiara Pagano with the artists of the If Body 2023 program to delve into each specific happening.

Chiara Pagano: As a multidisciplinary artist, you work with audio, text, still or moving images and sculpture: elements that, sometimes combined, sometimes brought together, generate connections to explore. What does it mean to navigate within this diversity of mediums, also considering your background in printmaking?

Holly Graham: Yes, my undergrad was Fine Art, so quite open and cross-disciplinary; I then went on to specialise in Printmaking at masters level. In some ways, that decision was counter to what I thought I was interested in previously—where I was excited by not being pinned down to a specific medium or way of working. But at the time that I applied to the course, the discipline of print offered a lens through which to think about lots of the things I was interested in. I have a particular interest in memory for example, both in individual ways of remembering and in how these malleable personal narratives come together to form collective histories, which are equally slippery. But I’m also curious about how these, in turn, form histories that we often attempt to concretise or make firm or static in some way. I’m interested in troubling those histories, reanimating them, questioning where the gaps are, and what lies in the spaces in between.

For me, print in terms of methodology, somehow embodies the processes of remembering—of repetition, traces, material degradation. Also, in the matter itself, I’m interested in duplicates, copies, these technological attempts to embed or fix down memory—photographs, text, moving images, audio—all the documentary records that we keep. So, I’m interested in print in its expanded sense.

I’ve spoken previously with friends about the promiscuity of print—the fact that it’s so embedded in society, it proliferates so much in our day-to-day life in different guises that we don’t even see it—it acts with and upon our existence. This is something I think about often, and it seems therefore appropriate that the work I make should also be fluid in form and shape-shift, according to whatever stories it’s trying to tell.

The combination of such different elements shapes stratified compositions. Layers upon layers become spaces to lose the self and find “the other”; territories to cross with ever-changing rhythms and intensities; compositional tensions that leave the viewer free to choose on which plane to linger for a second or pause for hours, opening new temporalities. This brings to me a quote by Holly M. Lewis in The Politics of Everybody: “by embracing nonlinear, non-Western thinking, postcolonial subjects could ‘decolonize the mind’ by rejecting Enlightenment values, the expansion of the sciences, and, thus, the rational use and abuse of others.” What does this stratification represent for you?

Thanks for such an attentive and in-depth reading of the work. Yes, layering, or stratification, definitely features in the work for lots of reasons, I think.

For me, it’s important not to dictate the way that people read the work, and I guess as I delve into memories and histories I’m also thinking about something that—as you say—isn’t linear. I’m seeking to interrupt a fixed or singular narrative to create multiple options for ways of reading, using for example collage and the possibilities of changeable configurations. They’re artworks that I have thought through really carefully, and there is a specific composition and placement that intentionally encourages, or might provoke, certain readings in the viewer. The works have their internal logic, but I guess I wanted to allow for lots of loose ends so that things can be read in different orders.

This work formally reflects the complexity, to some degree, of the research, and the entangled nature of the various histories and ideas I’m grappling with.

I started this body of work during a research residency at the British School at Rome. I was looking at formations of the blackamoor motif in Baroque Italian furniture design, and thinking about this in relation to other representations of blackness in Italy that had come before, which is obviously huge in scope. Then, to also think forward into our present space and consider how these formations and inscriptions of race echo into our time, projecting themselves onto racialised bodies nowadays. It’s so vast, there’s so much to look at and think about.

I’ve been talking about it as a repeated focusing in and then zooming out again, to consider different contextual framings. I don’t really have any conclusions from the research as such at this point, but little spotlights and observations; for this reason, the work can’t be an essay with a singular linear argument, with a beginning, middle, and end. I’m an artist, as opposed to an academic, so I suppose it’s unlikely that it would ever be that anyway. But yes, it kind of almost necessarily has to be unfixed, layered, complicated I guess, and in many ways unresolved.

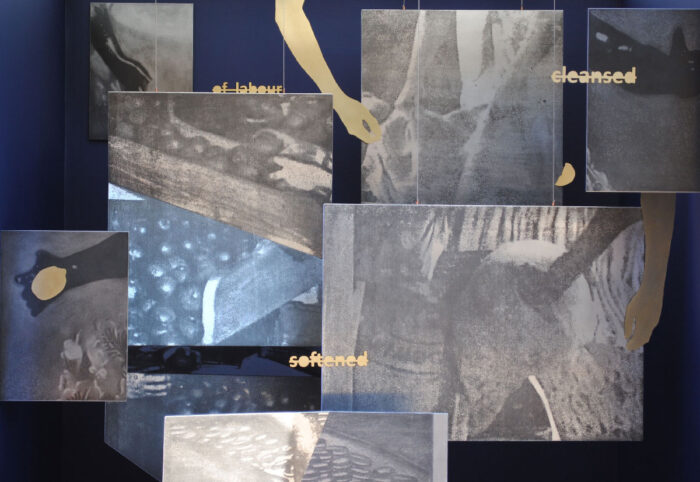

For example, I was thinking about the wall-based works that will be presented in the show at Lateral Roma on 28 September, almost as mood boards, actually. Reflecting on furniture design in relation to the blackamoor objects, which are themselves artisanal pieces of furniture, and mood boards as a form of developmental brainstorming. I envision the studio space and walls as this melting pot of the research and the thinking that I’m doing. That’s a layered space, where all these objects collide and come together and aren’t fully formalised or refined. So the layering, formally, also reflects that research process.

So yes, I’m glad that you talked about the embracing of the non-linear. I’m currently doing a short course on non-Western, African-centered methods of archiving, drawing on Pan-African ideologies. We’re thinking about countering violent practices of exploitation and silencing that are tacitly embedded in many Western record-keeping and archival systems and processes. Within that, we speak about cyclical time and reparative approaches to engaging with the past. It makes me think about cultural theorist Christina Sharpe’s call for us to “become undisciplined”, and Saidyia Hartman’s discussions of “waywardness”, not only as lived experience, but also as (an)archival practice, as well as the liberatory potentials of these ways of thinking and working against the Western dominant linear grain. I’m also reminded of historian David Olusoga’s discussion of a desire to move away from what he terms “history as recreation”—of contemporary critical conversations that express a desire to shift away from an expectation for history to perform in a simplistic and singular reification of celebratory nationhood; to instead allow it to be multiple, muddy, messy, complicated, and to expose and make transparent structures of power, domination and failure.

So while the works may in some ways present as quite polished in their construction, I also want to embody some of that playful undisciplined, unfixedness, complication, and layering that you speak about. They bring elements together that might rub up against each other weirdly. There are certain things—such as certain material processes that I’m using or imagery I’m channelling—that might not feel directly related across time and space historically, but which I feel resonate between themselves poetically. For example, the marmo africano imagery, amidst the craft process of ebonising; the mottled surface of Murano glass-blowing are all very different reference points, but I read ideas around movement, place, colonial expansions, craft, art, artifice, naming practices and more into them.

Speaking about your time in residence at BSR in Rome, and your research of the motif of the blackamoor you just explained, it feels to me that by opening a crack in time, you let the past break into the present to disturb modern Western society’s racialized forms of representation. Can you tell us more about this research? What is your approach to history and how this research led you to develop all the new works which will be presented on the occasion of If Body 2023 in the spaces of Lateral Roma?

I had already started exploring this topic previously, in some of my other work: thinking about European representations of Blackness through the motif of the blackamoor. Previously I was looking at it within ceramics, specifically as a design trend that took the form of figures flanking sugar-bowls, so I was looking at domestic artisanal objects.

The research I did led me back to the influence of Italian design in particular, and to classical roots within this motif. So I’ve been reflecting on holding gestures of the atlas figures and caryatids, as well as thinking about traditions of craftsmanship, woodworking and furniture in Northern Italy. There are examples of this motif that I found in Rome. Some of the earliest examples are in the furniture of Palazzo Colonna: like cabinets and tables supported by mori. They’re termed mori (or Moors), and listed as such in financial records of the time, but they are actually intended as representations of the Ottoman Empire. They’re victory trophies or symbols of the defeat of the Ottomans by the Papal States in the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, in which the Colonna family was heavily involved.

So yes, I’m interested in the development of this motif, the conflation of identities, and what it means for racialized bodies and representations of otherness. This research led me to examine all sorts of representations of nations. There are several maps and special collections in the BSR archives that are early cartographic examples that also feature allegorical renderings, caricatures. Reflecting upon how these readings are formed, led me to Bernini’s Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi in Piazza Navona, where the four rivers speak of the “other”—the shrouded head of the Nile of Africa is represented as a sort of exotic unknown in terms of its source, which can be read onto the othered or exotic subject in a broader sense; and the shackled representation of the Americas, the New World seated amidst gold coins, as this newly perceived potential site of commerce, open to exploitation. There are links in turn there to the Livorno monument, which apparently may have influenced this work in Rome. The research feels quite expansive and I’m interested in how these ways of viewing the world through a sort of White European lens have shaped and continue to shape contemporary lived identities.

It’s been a peculiar journey because my understanding of Italian history is fairly elementary, and most of my prior knowledge has come from a British context, via transatlantic histories in which Italy was less involved in. But Italy clearly does have relationships with race which are problematic, and we see these operating through its colonial histories and through legacies of migration, as well as the racialised nature of the current migrant crisis. I had some encounters in my 6 months, which displayed how these dynamics are enacted upon bodies of colour and Black bodies in contemporary Italy. But I’d love to have further conversations about the multiple ways that these things play out today.

The interesting thing about the If Body program is that it does speak about the body, it all comes back to the body. So, these objects are representations of othered bodies, and in the work I’ve made, part of this bodiliness plays out through material interrogations and representations of skin, artifice, surface, fiction, etc.

In conjunction with your solo exhibition curated by LOCALES within the If Body program, you will also hold a participatory workshop. Can you tell us more? With whom will you collaborate and what will it be about?

I had wanted to develop a workshop to take place alongside the exhibition, as part of a collaboration with curatorial initiative On Site and the British School at Rome, but that’s not happening due to time limitations and some other factors. The desire behind it was to create a discursive space for and with people inhabiting racialised identities in Rome to think and speak around how conceptions of race act upon bodies in space today. Again, I’m aware that it’s a really different context from the UK, so I’d be interested to speak through parallels as well as differences in how that occurs across space. The idea was that it would be open solely to people of colour, to create a space as safe as possible, knowing that these conversations can be quite vulnerable.

That’s not happening on this occasion, but there will be a reading and an in-conversation in collaboration with the BSR and On Site; it will be kindly hosted by bookshop Libreria GRIOT, whose focus is on promoting work by writers of African and Middle-Eastern descent.

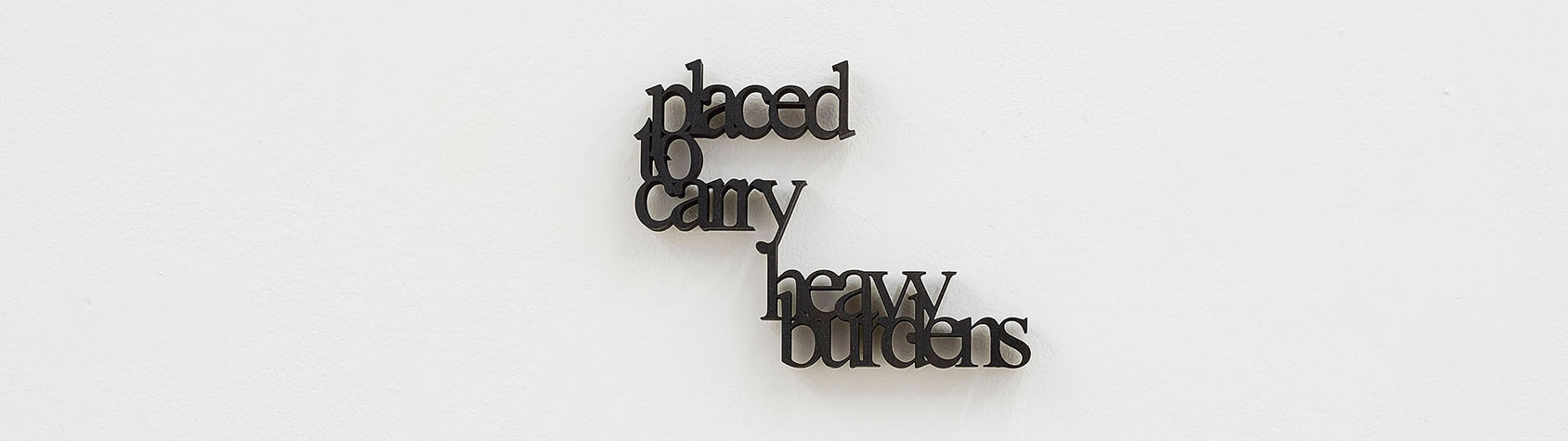

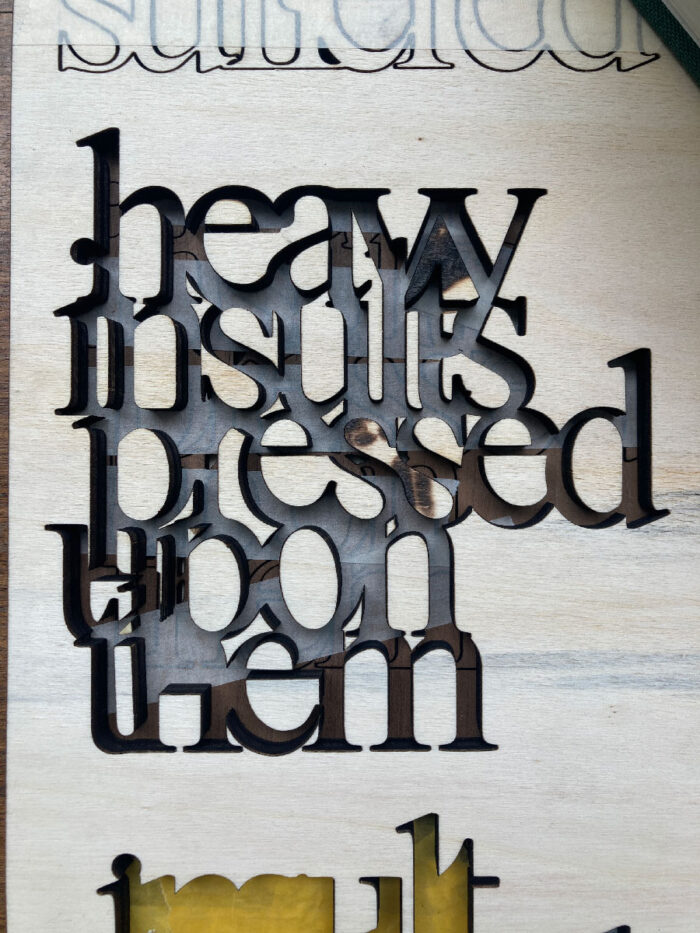

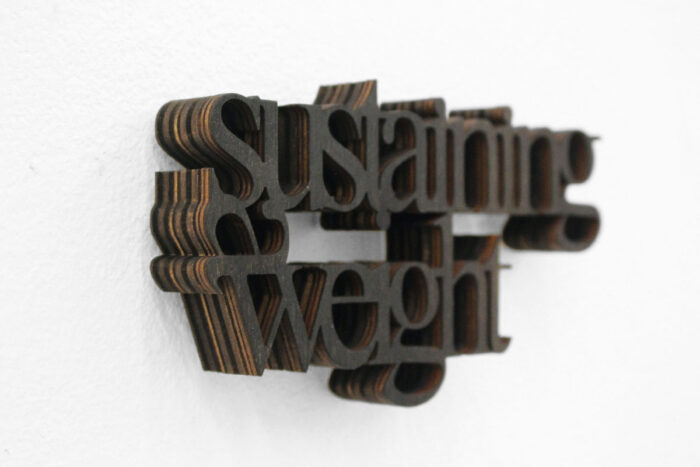

Much of your research reconsiders how collective memory and history are constructed. The word, in this rethinking process, takes on an extremely significant role. I am thinking, for example, of your work Sustaining a Weight. By carving wood, a new materiality comes to life. What is your approach to language about the doing and undoing of certain narratives?

I’m interested in multiple voices, and I enjoy writing. While in Rome I was writing in quite a fragmentary way—kind of responsively, reflecting on the things that I was seeing and taking in. One thing I was drawn to was an extract from Vitruvius’ text De Architectura, that offers an origin story for the architectural motif of caryatids—female forms standing in place of columns as structural supports for buildings. He also speaks about telamons, performing similar functions as punishments often symbolised by a victorious state representing their defeated enemies in a position of eternal servitude and labour. The original version is in Latin and the copy I had featured a direct side-by-side translation into English, but when I was reading other texts about it, they would have other translations. Through this, the language morphed and shifted, but was also self-referential. I was interested in how this conversation around weight and burden was spoken about and framed. So, yes as you say, the wall texts that I developed originally for a group show at the BSR titled On the Meaning of Gossip, they’re laser-cut plywood and then layered to create a sense of depth. The text in itself is fairly light and spindly, and it’s just in Times New Roman, the same typeface as in the printed material that I was sourcing from. But I wanted it to feel dense or heavy, hence the layering and the thickness of the material, to play with that, linguistically.

There are multiple translations here alongside the direct slippages of language. There are translations through time and our understanding of the motif. Vitruvius’ readings were critiqued at later points as being erroneous, but regardless, his interpretation had a huge influence on subsequent architectural design. So these ideas around punishment, and silencing, became entrenched in that motif. And that’s definitely what we see with the Colonna blackamoor figures. In the wall texts, the translators speak in different voices but reinforce each other.

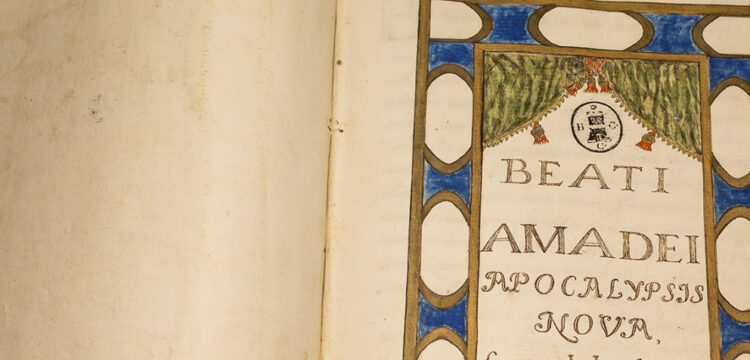

As mentioned, I’m also interested in having something that isn’t singularly linear but fragmentary. I return frequently to thinking about polyvocality throughout my practice. An element of this body of work is a more extended accompanying text that embodies a lot of quotation. It lifts directly from the canonical texts, such as De Architectura, but aims to cycle back and probe at, and eventually undermine altogether, the idea of a canon.

When last in Rome, I received an invitation to participate in a reading event at the Swiss Institute, hosted by artist Sophie Jung. This opportunity allowed me to bring together various texts I had been working on. The event centered around the exploration of canons, with a particular focus on critiquing and deconstructing prevailing narratives and voices.

The current capitalist era is characterized by chaos and a strong sense of physical or psychological suffocation. How do you think art can move toward identifying emancipatory strategies that can provide tools for new breathing, giving back a voice and a space to all (human and non-human) bodies?

This is really difficult. I think art and art-making are so entangled in the capitalist framework that we’re operating within. Capitalism is often referred to as coercive, which I find a really useful term in trying to understand the complexities of existing in, surviving in, and becoming complicit in these structures; in spite of not being aligned with these ideologies, and being aware of how they harm us. I say that to acknowledge the neoliberal web that art, as a sector, is entangled within. I feel incredibly aware of the compromising positions in which artists are often placed, which can limit the ability to “imagine otherwise” as Lola Olufemi puts it.

My work aims to critique, in order to instigate reflection, conversation, and dialogue. So many artists are making incredibly important work to probe at and critically engage with our current lived experience, and that comes again back to this idea of restorative work and practice. The work I’m doing in the show is a mapping, a charting, an attempt at understanding some of the conditions that have shaped racialised lived experiences today. I’m sceptical of what it can do beyond that, but I do think of the work as facilitating a way of speaking back to a trope that is in many ways violent, degrading and silencing. So perhaps there’s a “giving back voice” there.

To draw more upon your words—“breathing, giving back a voice and a space to all bodies”—I think of the writing of Alexis Pauline Gumbs and her piece Dub: Finding Ceremony, which draws on the work of Sylvia Wynter to think about this connectivity. Within the work, there are considerations around how colonial histories enact themselves upon bodies—all bodies—and a call for closer cross-species relations, an awareness of how interlinked we all are. The text is beautiful, and I watched an online reading where she delivered it as a ceremony—it was interactive, and used in dialogue responsively with people in attendance.

I think a lot in my practice about what Christina Sharpe frames as “wake work”, which again is in the context of the transatlantic Black experience, thinking about the work conducted in the space of being in the aftermath, being in mourning, being alert and watchful. She talks about this work as a real conscious act of care, that can be a liberatory practice emerging from the confines of living in the wake of oppressive and violent histories and amidst the continued reverberations of those pasts. I find that a very useful framework in terms of thinking through some of what you’ve mentioned.