Surface Tension

A conversation with Maria Domenica Rapicavoli

Maria Domenica Rapicavoli’s works explore conditions and experience of power, alienation, displacement and invisibility through a punctual critique of global, economic and political systems. She calls into question dominant historical narratives, disrupting perceived notions of contemporaneity, by looking into the materiality of evidence and knowledge. She constantly seeks to make tangible how economic, political and military structures of power are reshaping our everyday lives. The first retrospective of the artist at UB Art Galleries in Buffalo and the homonymous catalog Surface Tension (Mousse Publishing) cover the last decade of the artist’s heterogeneous production, while the video installation The Other: a Familiar Story showed at ICA in Milan deals with the act of “othering” following a woman forced to emigrate to the United States through marriage against her will, leaving her children and partner behind.

Jacopo De Blasio: Surface Tension is a distinctive feature of liquids, a physical phenomenon that brings some objects or creatures to float—to “walk” on water. It is also the name you chose for your exhibition. Who or what’s keeping afloat?

Maria Domenica Rapicavoli: The ability of a liquid to resist an external force due to the cohesive nature of its molecules is defined as surface tension. It is a phenomenon that remains invisible until an interaction between liquid and object occurs, and it is precisely this interplay that draws my attention: on the one hand, the object that exploits tension while living in a state of precarious balance and, on the other, the liquid acting as a repelling agent. This tension is, by nature, very easy to break. I see it as a metaphor for our society in which social, political, and economic tensions are often invisible. When they occur, all the parties involved must maintain a balance of forces not to sink.

The works Crooked Incline and A Cielo Aperto examine the way the military maps the airspace. How can an artwork destabilize, disorient, and escape all forms of control?

Art is presented through various forms, meanings, and purposes. I don’t think there is a single direction in this multiplicity. When I start a project, I am driven by something that destabilizes me and that I need to tell visually, so I try to transmit this urgency in my work and, finally, pass it to the spectators. It will be up to them, then, to allow my work to disorient them.

You conceived and realized both Reminder and If I am in Pieces Is Easy to See? during the lockdown. How did the pandemic affect the collective perception of time and space?

Domestic space replaced the external one. Mental space, instead, was filled with thoughts, and the limited space of the digital screens invaded our lives. Time has expanded while space has shrunk. It is precisely in these circumstances that, upon the invitation of Magazzino Italian Art in Cold Spring, NY, I made both Reminder and. If I am in Pieces Is Easy to See from home, in my tiny apartment in New York, because I couldn’t go to my studio and work during the lockdown. I turned my kitchen into a ceramic workshop and my bed into a movie set. I spent countless hours modeling hundreds of clay pieces to recreate a pile of broken glass that I found on the streets. Every day I waited for the arrival of a sunbeam that entered through my window to photograph it and mark the passing of time. Reminder consists of a series of photos and texts that I wrote to express my frame of mind during those months: a coexistence of disorientation, frustration, a sense of rupture, and fear. I think it was something close to what the community was feeling at that time.

Where do manual intervention and latest technological innovations meet in your work?

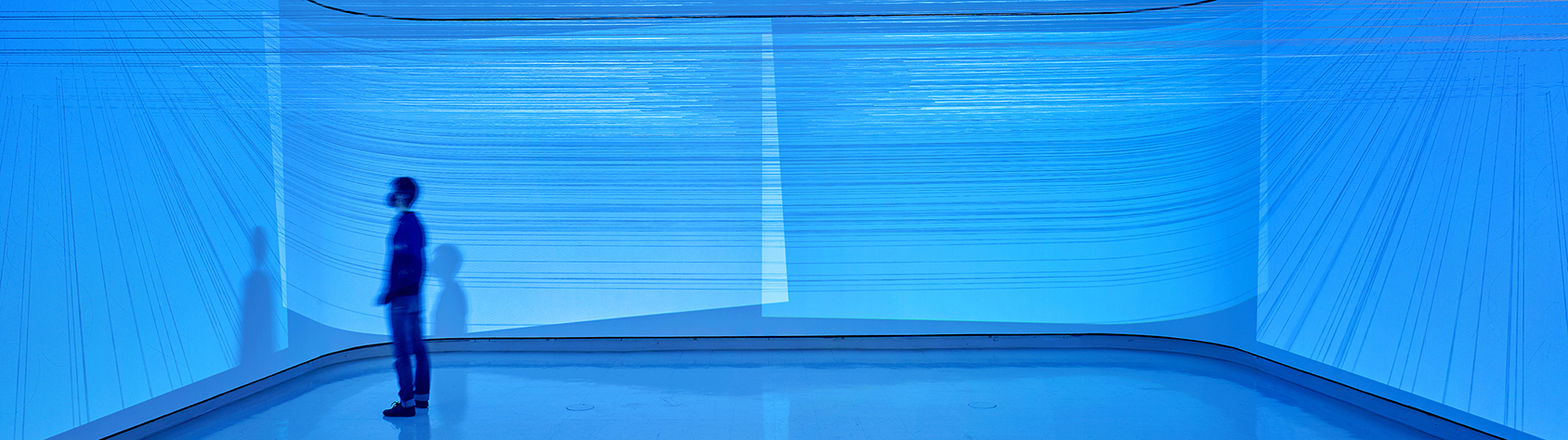

I remember that, as a child, my favorite book was a volume of I Quindici, an encyclopedia for children, entitled How Things Work. This question, along with “why do they work like that,” has always been the driving force behind my research. I didn’t become a scientist, but I think this explains how strong the bond between the two disciplines is for me. Almost all my sculptures require a very long handwork time and much meticulousness. For the installation of A Cielo Aperto, I glued thin plastic wires to the walls to recreate the air corridors of military drones. For Crooked Incline, I modeled geometric shapes in porcelain reminiscent of the bombs fired by airplanes during World War II. I sculpted a telescope by hand for A Starry Messenger, following a long removal process and sanding. Together with the imperfections that are typical in handwork, all these elements clash with technological work—often associated with speed—that inspires the contents of my work. The contrast between temporality and efficiency marks a human intervention that is anything but “perfect,” yet unique.

A Starry Messanger refers to Galileo Galilei’s Sidereus Nuncius. Thinking through the complex relationship between science and art, what is your take about the ever-evolving interdisciplinary nature of contemporary art?

Interdisciplinarity in art is a natural expression that has been manifested for a long time and whose development in video art, for example, is shifting towards augmented or virtual reality, methods that, I think, will—soon—replace the traditional use of the screen. A Starry Messenger is the English translation for Sidereus Nuncius, the text published by Galilei in 1610 containing his astronomical observations, including the discovery of the moons around Jupiter that enraged the Catholic Church. Socrates Park commissioned the project in Queens, NY, as a work of public art, and, in this sense, the combination of art and science has become a cognitive tool accessible to all. The telescope works, and, on its inside, between the two lenses, it is possible to see different images of the earth captured by satellite surveillance systems. These are random images found on the internet, revealing close-ups of other points of Earth’s surface. While making his first telescope, Galilei did not consider that the sky could observe the Earth thanks to satellites. Since forever, the telescope has been considered a tool of knowledge, whilst the work tries to emphasize a system of control, that is everything but poetic.

In The Other: A Familiar Story all the different points of view counterbalance the narrating voice. The silent cries of the protagonist, as well as the black bands on the eyes of the diners, evoke an opportunity for discussion rather than a univocal point of view. Would you like to explain this choice?

The Other: A Familiar Story is based on a true story of a woman in my family who was forced to marry a husband who raped her and subsequently followed him in the United States at the beginning of the twentieth century, leaving her children behind in Sicily. It is a history of gender violence, abuse, patriarchy, alienation, and invisibility, conditions familiar to those who emigrate. As the narrating voice says at the beginning of the video—“The voice you are listening to is not mine, neither the story I am telling, but it is close because it is made of the memories of those who knew me and heard about me.” There have been many voices among the women of my family that handed down this story to me, as many as the voices of those women who have a similar account to tell because they have experienced it first-hand. The video was designed and produced on two channels to recreate a dualistic vision based on the concept of the Un-Heimlich, the “uncanny” which, according to Freud, is a state where alienation and familiarity coexist. My protagonist has never been allowed to talk and, therefore, listened to. The work develops much around the notion of alienation and invisibility, typical conditions of those who emigrate and those who are victims of domestic violence. The mannequins in the lunch scene are the children of the protagonist. Their eyes are covered because I hoped they would not see and absorb all that suffering.

In our collective imagination, women are often associated with vulnerability and the need for protection, especially in the war paradigm: the body of a woman becomes the symbolic space of a conflict. How can we question these cultural patterns and habits that are still part of our way of thinking, seeing, and acting?

From the patriarchal point of view, a woman must be fragile so the man can impose his strength to control her. However, the paradox is that she should be protected from men by other men because I don’t see any other enemy. In The Second Sex (1949) Simone De Beauvoir explains how in patriarchal society, women are seen as “other” compared to men that are “absolute”—and therefore authoritarian and dominant—beings. This is an attitude that belittles the role of women, and I think that it can be suppressed only by its overturn. Gender equality, independence, and women’s freedom must become absolute rights.

Sexual iconography plays a vital role in the construction of political ideologies. In this respect, the female personification of a nation—often invaded by a foreigner—is one of the most used metaphors. Sara R. Farris coined the term femonationalism to describe the exploitation of feminist claims by the far right, according to which the principle of equality would paradoxically be reduced to a clash of civilizations, assuming Islamophobic and racist traits. Do you think that’s an actual risk?

Of course. As I have said previously, the hegemonic issue determines instrumentalization. The individuals making these speeches are always white men who rule and constantly assert their superiority of gender and race. Therefore, they have little to do with feminism and gender equality.

You have shown The Other: A Familiar Story for the first time in Italy, at ICA in Milan and at Museo di Castelbuono in Palermo. Have you noticed any significant difference in the public response, compared to the past exhibitions in Germany or in the US? How does cultural heritage affect the fruition of this specific artwork?

The Museo Civico di Castelbuono in Sicily acquired the work, and I had a presentation of the project in January. In Milano, at Fondazione ICA where I could install the two-channel video installation in a separate room, I received very positive feedback from several people who contacted me to tell me how directly or indirectly connected they were with the topic of the work. There was definitely a stronger response in Italy than abroad. Patriarchy and domestic violence as well as women rights, are relevant topics in Italy now, probably even more than in other countries. I believe that, although the feminist movement awakened many people’s consciousness in the 70s, there is still a lot to do, if we think that in 2021, 116 women were killed by men, 100 of then in domestic environment. Therefore, the story I narrate belongs to many women nowadays as well as it belonged to the protagonist of my video a hundred years ago. Luckily women are more responsive and awake and I am faithful that a new, better story can be written by future generations.

Who is the other for Maria D. Rapicavoli?

“A subject affirms itself only through opposition. An object is what the subject perceives as different from itself.” In the video The Other: A Familiar Story, I begin with these words. Thus, the other is never the subject. So in order to exist the subject has to make sure that there is always an other to be opposed to, as something to impose its superiority on. The other is always in a minor position. The other is the different, from a sexual, racial, social, economic, military, or political point of view. In my imaginary instead, I see only subjects, all equally different.