Supernaturalist Listening

A proposal

This article is an apocryphal admixture of a forthcoming chapter coauthored by Monteanni and de Seta (2025), a critical text written by the same authors for Akhet’s first artifact and compilation, Monteanni’s own audio essay Supernatural listening and geotraumatic timbres presented at Gasworks in 2024, the radio broadcast Spirit Media by Monteanni and curator Jessica Kwok on Montez Press Radio and a forthcoming speculative audio-text experiment in ghostly transduction through AI (2026) that the authors executed at SOAS and the Faraday Memorial, London, in July 2024.

The authors would like to thank Juarta Putra, Harry Koi, Alberto Ricca, Riar Rizaldi, Jessica Kwok, Gasworks, Montez Press Radio, Lorenzo Chiarofonte, Tommaso Monteanni, Teguh Permana, all the visible and invisible spirits, electrical impulses, the ancestors and audio technologies.

“In Indonesia there’s this Javanese song called “lingsir wengi” that is believed to summon kuntilanak (a lady ghost much like the one in The Ring in appearance). Maybe someone should try playing it with a speaker in other parts of the world to see if the ghost appears.”—u/Enotonom (2020), “Anyone had experiences with cursed/haunted music?”, r/Paranomal, Reddit

Introduction: Shadow Box, an experiment in audio supernaturalism

Shadow Box is a composition developed by audio researcher and musician Luigi Monteanni, aka Neurotica Exotica, 1/2 of digital folklore duo Babau (Artetetra Records/Discrepant/Communion)—and Teguh Permana, aka tarawangsawelas (Morphine Records/Latency).

In this audio composition, the artists combine three types of audio technologies believed to be able to allow communications between humans and spirits or ghosts: the tarawangsa, Spirit Boxes, and accordions. Shadow Box dramatizes and reflects on different audio languages used to link visible and invisible worlds through the inherent human preconception that sound and music—physical phenomena which are also invisible—function as forces and flows bridging these two overlapping but parallel realms. Let us first introduce these three audio technologies.

The tarawangsa is a regional musical style developed in the hills of Rancakalong, Sumedang regency, in West Java, Indonesia. The term “tarawangsa” refers to a vertically-played chordophone composed of two iron strings played with a bow, which is accompanied by an horizontal zither plucked with both hands, the jentreng. The genre is usually played for the area’s harvesting ceremonies and human milestone celebrations, ritually inviting the ancestors’ spirits to participate in the life of the community by causing trances and delivering messages while protecting the village. For these reasons, tarawangsa operates as a musical technology facilitating communication between the village and the spirit realm.

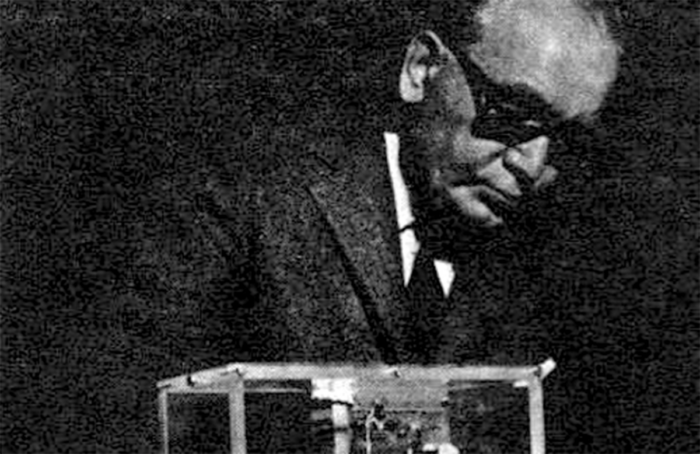

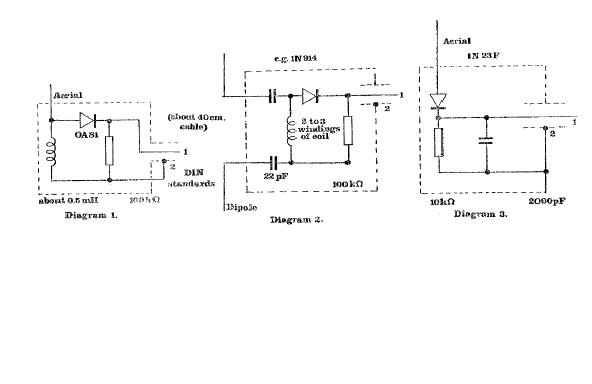

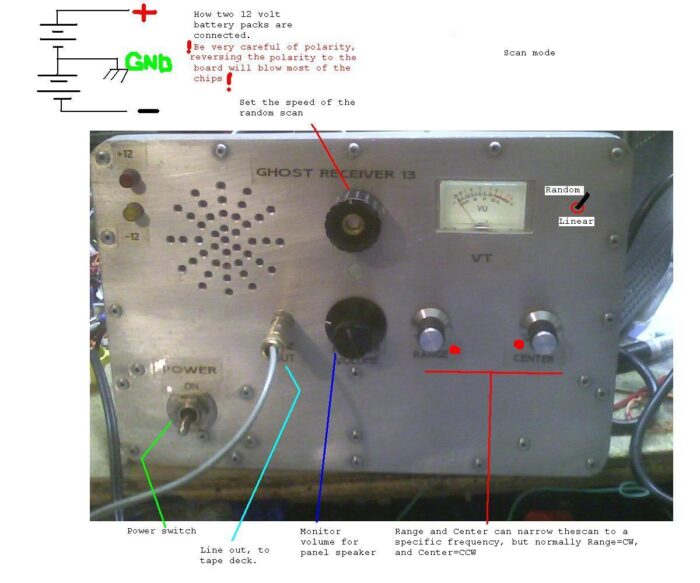

Spirit Boxes are devices invented by Frank Sumption in 2002 which can theoretically facilitate spirit communication by allowing their users to voice simple questions for otherworldly entities through the device, which picks up Electronic Voice Phenomena (EVP) by fast-modulating AM/FM radio frequencies thanks to a special kind of electric component: the Raudive diode. Konstantin Raudive was a student of Carl Jung and a Latvian psychologist who taught at the University of Uppsala, Sweden, before devoting the last ten years of his life to EVP and the emerging field of Instrumental Trans Communication (ITP). He experimented with his own spirit radios and invented the “Raudive Diode Receiver,” an audio recorder in which a Germanium diode plugged in place of the microphone was supposed to capture radio signals from the afterlife. Raudive stressed that his device worked because spirits have access to their own radio stations—an argument that has yet to be proven.

Finally, accordions—which in the Shadow Box track are sampled and replayed by Monteanni—are a family of box-shaped musical instruments belonging to the bellows-driven, free reed aerophone family (in all of which sound is produced by air flowing past a framed reed). The accordion’s distinguishing feature is that it combines a melody section on the right-hand keyboard with accompaniment or basso continuo functionality on the left-hand side. Ever since the Scottish psychic and medium Daniel Dunglas Home (1833-1866) reported that an accordion would either play when completely untouched or while being handled in such a way as to render a musical performance impossible, the instrument was believed to be able to invite spirit communication. The hypothesis behind this belief was that because of its air pressure-based activation, invisible entities could emit sound by entering the instrument and manipulating the air around it, once again linking the invisibility of both sound and air with supernatural phenomena.

Shadow Box was composed by creating a call and response circuit between these supernatural communication systems (the tarawangsa music, the accordion and the Spirit Box signals) by feeding the recording of an original tarawangsa melody improvised by Permana into the box. The melody was executed with the specific intention of calling and conjuring ancestor spirits. The entire duration of the improvisation (approximately ten minutes) was then played back through loudspeakers into a room where a Spirit Box was turned on and in receptive mode. The Spirit Box’s output was in turn recorded to document how the device functions as a transducer of supernatural realms and how their inhabitants behave when stimulated by the instrument. Accordion drone lines and an improvised spoken word by Monteanni (at minute 04:18) were added to the edited recording, which was later processed imagining how it would sound if it came out of the afterlife through a Spirit Box. Monteanni and Permana produced the recording during 2023 in Rancakalong, alongside the realization of another audio project.

After four recording sessions (for a total of approximately 40 minutes), only one line of speech—probably a clear radio signal mangled by various frequency cuts—was picked up (at minute 02:07), while the timbrical variations of the Spirit Box revealed a whole new universe of buzzes, hums, hisses and strangely polyphonic noises. Whatever one’s beliefs about the possibility of communicating with spirits are, the ambiguity of what a Spirit Box can produce in terms of message outputs (still a contested matter even in the ghost hunter community) invited us to imagine that spirits could be able to react to instrumental, timbrical stimuli by manipulating tonal and textural output signals, thus improvising alongside our music by resounding their own otherworldly soundscapes.

What if spirits felt invited to listen and follow the music instead of replying to our closed and limited questions by means of stuttering vocal messages? What if communications from beyond—from the other side of the AM/FM white noise, the metonymic threshold of life and death—are more similar to lo-fi, bitcrushed polytimbric soundscapes full of bitrate reduction artifacts and electroacoustic short-circuits rather than to verbalized shards and splinters of semi-coherent thought? These are all questions that Shadow Box brings to life in the listener’s ears.

To delve into this gray areas of concealed audio spaces and distant geographies (England/Indonesia, life/afterlife, this/that side of the instrument/device, transmitter/receiver systems of mediation) means to precisely suspend the preconception that the outcome or meaning of a signal is predictable and understandable and that audio spaces (reverbs, convolutions, bodies, rooms, materials, refractions, etc.) are completely imaginable and definable through audio-decoding practices. By hearing through these technologies – be they electronic devices to talk to spirits or ancient tunes able to gather the ancestors – one listens in equal parts (1) to oneself, auscultating one’s own capacity to tune in and out of the aural self-deception of hearing a ghost sound, (2) to the will to listen to something, to recognise something supernatural in sound, (3) to one’s capacity and attempt to decode this ghost sound into a coherent response and (4) to the speculations about how these signals may travel through a medium, being transformed by their transitions and being answered by equally negotiated and processed sonic emissions.

As a result, Shadow Box—a title alluding to a physical object whose content is impenetrable – confounds and collapses the boundaries of two parallel two spaces, immersing both positions of transmitter and receiver into a sonic soup of reciprocity and ambiguity, transforming them into vectors conveying information about two sides of a communicational chain. The tune is a gravitational center pulling onto two sides of a transmission which are superimposed into an opaque nexus. Geographic, phonic and supernatural location-spaces neurotically transform into one another, tending towards an impossible attunement based on a structural interpretative uncertainty. The technical possibility of a communication based on a rediscussion of what reality means in the realm of audio mirrors an embodied speculation about how things look (and sound) from the other side of the threshold.

As an audio device, Shadow Box aims at bridging the histories and practices of audio signals, supernatural communication and modes of listening to audio artifacts without being able to offer neither a map nor an explanation of these new ambiguous zones of emergent listening. In a way, we believe that this happens because operating with these devices and in these liminal zones of perception brings spirit mediation towards the realm of technological mediatisation in a way that eliminates the necessity of a human medium as a decoder of signals and waves, such as the trance master in tarawangsa ceremonies who facilitates the invitation, control and interpretation of the spirits/signals.

These speculative investigations shift the discussion from what it is that we are talking about when we try to comprehend the role of a spirit medium, to what we are talking about when we deal with spirit media—the haunted channels and conduits facilitating, amplifying and influencing the passage and transduction of supernatural messages and entities. How do these operate? How does sound change when transduced this way? What role do technologies play in this process? In the following paragraphs, we try to sketch a theoretical framework for this topic by exploring different modes of listening beyond naturalist listening—unnaturalism, supernaturalism, hypernaturalism, ultranaturalism—by analyzing and comparing the practices of ghost hunting and sound-mediated spirit communication.

Ghost thresholds: Mediating unnaturalism

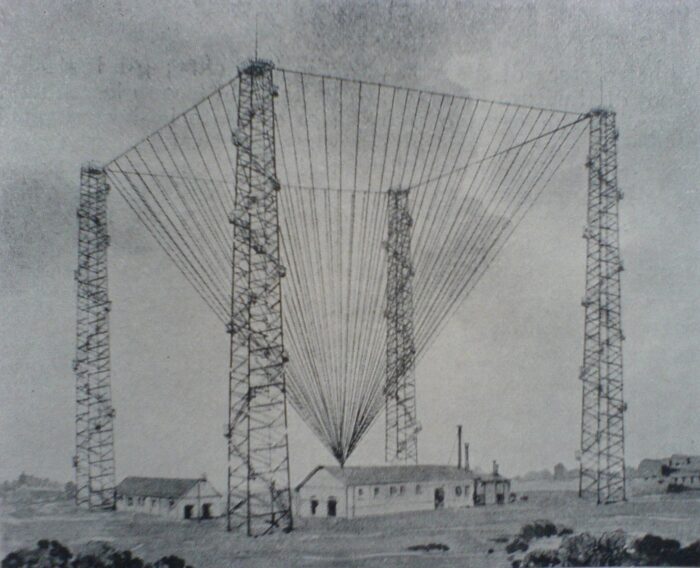

On the 12th of December 1901, at the Marconi Poldhu Wireless Station in Cornwall, while trying to catch the first radio signal to be transmitted across the Atlantic, Guglielmo Marconi heard a familiar sound confirming the activity of the transmitter. The radio was working. And yet, the inventor’s exceptional success story in overcoming the technological limitations of his time was later disproved by research, which showed that the transatlantic transmission had in fact been impossible given Marconi’s limited equipment. Field recordist Sebastiane Hegarty, commenting on the episode, hypothesizes that Marconi had «tuned into what he wanted to hear; perhaps the signal came not from Poldhu but from the labyrinths of his imagination or the auscultations of his own listening».

After that, Colonial writer Rudyard Kipling’s 1904 story “Wireless” exemplifies the overlaps between natural and supernatural signals. Recounted by an anonymous narrator, “Wireless” tells the story of Mr. Shaynor and Mr. Cashell, a gent with an amateur interest in wireless telegraphy. As the story goes, the narrator prepares a strong liquor to treat Shaynor’s cough, who passes out shortly after downing it. Meanwhile, Cashell is in the room next door trying to send Morse code to a friend. Unfortunately, Cashell tunes into the transmissions from two ships in the English Channel. Suddenly, the intoxicated Shaynor begins to recite John Keats’ poetry. After the radio communication issue is resolved, Shaynor wakes up. When questioned about his poetry recitation, Shaynor affirms that he had never read any of Keats’ poetry.

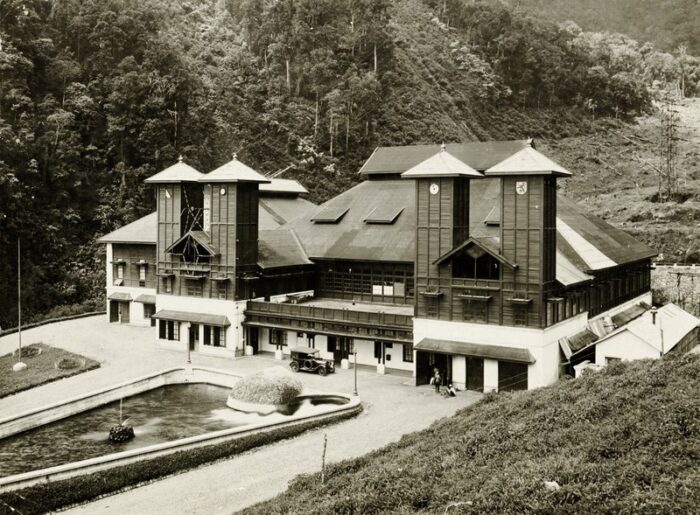

In his movie and book Tellurian Drama, Indonesian artist and filmmaker Riar Rizaldi (2020) imagines the classified story of Radio Malabar, the first colonial radio to appear in West Java, Indonesia, built by The Dutch East Indies government and inaugurated on May 5th, 1923. While the entire work gravitates around a mysterious essay written by Drs. Munarwan, a pseudo-anthropologist and geologist concerned with the possibility of geoengineering the planet through the radio’s obsolete technology, Tellurian Drama is also partly about the potential overlaps between media, communication technologies and the invisible world of spirits and ancestors – a fraught encounter of material and immaterial worlds and worldviews. By detailing how gunung Puntang, a mountainous location ripe with both supernatural and natural energies, has helped colonial government logistics in the installation of radio infrastructures due to its geological and topographical features—i.e., two twin mountain peaks of similar height proving ideal to install the radio, allowing intercontinental communication between Indonesia and the Netherlands over a 12.000 km trajectory—Rizaldi subtly theorizes how signals, radio frequencies, spirits, technologies and the unseen overlap and intermingle in an invisible space delineated by transmitters and receivers, listeners and speakers. For the purpose of this essay, the key implication of Tellurian Drama is that, at least to a certain extent, spirits like the Sundanese ancestors (Karuhun), move, travel and operate in an analogous yet never identical way to sonic signals and radio frequencies. The techno-natural assemblage of mountain peaks and antenna cables amplifies the reach of signals: through the parallels sketched by Rizaldi, we can see how this applies to both the wireless signals boosted by the infrastructural topography and the activity of spirits energized by the natural environment—technology is both cultural and supernatural.

In all these historical and fictional accounts, listening, recording, transmitting and receiving are technological acts tangled with subjective, psychological and even supernatural dimensions. Humans, as much as microphones, radios and even planets, decode information and transmit it. While, in its classical definition, listening brings us to consider the content of audio and to ask: “What is it that we are listening to?” in Rizaldi’s work the content is an opaque object, a black box. What we are left with is a transmission, a mesh of impulses and sources. In Tellurian Drama, audio is not an object; it’s a process making things happen.

While Rizaldi’s media theoretical speculation has to be contextualized in the domain of genre cinema such as sci-fi and horror, the comparison between spirits and frequencies, ancestors and signals is more than a fictional device; in Indonesia, well tuned instruments and correct musical execution are, in spirit ceremonies, capable of building a “bridge” between humans and spirits, allowing phenomena of spirit possession and mediumistic communication to take place thanks to a literal synchronization of spiritual frequencies, nyurup. This capacity of sounds, music and noises to create channels of communication with spirits in Bandung resonates with Rizaldi’s speculative fiction and hints at a model of mediation that is opposite and perhaps complementary to the one underlying technological approaches to the unnatural, such as 21st-century frequency scanning and high-tech ghost hunting.

On the 7th of July 2024, the authors of this essay met at Elephant and Castle, London, with a Spirit Box and an array of audio devices to conduct an experiment in sonic denaturalization. The location was chosen because of the presence of the Faraday Memorial, a massive steel box situated on Elephant Square which contains an electricity substation for the Tube and is lined with copper, creating the effect of an actual Faraday Cage. The Memorial shields its insides from electromagnetic signals such as radio transmissions and mobile phone calls, making it the ideal place to conduct experiments in ghostly communications: if we hear something from the Spirit Box, it can not be human radio signals, as their waves cannot travel in here.

Although the place is at the center of a major road, its alien-looking, smooth and reflecting surface – something like a T-1000 version of the Lemarchand cube—makes it almost unnoticeable. After all, this is just a gigantic metal box, perfectly camouflaged in the dystopian urbanscape of London. A legend says that none other than Aphex Twin, mesmerised by the weird allure and mystery emanating from the box, has secretly resided inside it, using the Memorial as his studio and abode for a period—a story which has alas proven to be a rumor. After several attempts at breaking into the box by circling around the structure, we find an open door and move in swiftly without anyone noticing. The inside of the place is strangely cold, probably due to the metal reflecting the weak British sun. The monument feels oddly bigger than it looks from the outside. Cables and unidentified electrical machinery produce a lowercase hum providing a metallic quality to the air we breathe.

We set up our gear: a computer recording via Ableton the audio travelling from a Zoom Hn4 Pro and a Spirit Box SP7T on separate channels through a cheap Focusrite sound card. The sound card’s output is linked to a speech-to-text AI model fine-tuned on thousands of hours of audio recordings of communicational rituals from around the world, which could help us transcribe possible utterances. Through this setup, we want to probe processes of supernatural computation to see if they would enhance or hinder supernatural communication. We try the signal processing by saying “Hello” in the mics just to see it appear on the screen as a text.

We are about to run two blind tests with the box by only using our voices. The rules are simple: while one prompts questions for the entities through the Spirit Box, the other listens to the device with a pair of good, closed headphones transcribing all the possible words and sentences they are hearing. This way, it is impossible for the one transcribing the words to know a desirable output that a question might need. There is thus no way for the interviewer to fall under the typical self-conditioning processes through which psychoacoustic listening produces, as in Marconi’s case, the desired outcome in the form of coherent answers. Both of us have prepared a list of questions that we don’t show to the other. Through this test, by taking up a task that would appear entirely implausible according to normative modes of listening—understanding spirits through a cheap radio—we abandon the framework of sonic naturalism: the idea that sound is (mis)understood to exist “out there” in the world, pre-existent to social interaction and mediation, and that all sounds are created or emitted from unequivocal places.

This kind of sonic naturalism goes hand in hand with various ideologies of audio realism according to which, when it comes to sound recording and reproduction, higher signal quality and multi-channel stereophony correspond to a less mediated and more detailed access to an immanent ‘audio truth’ that lies beyond the technical limits of the medium. Particularly evident in the domain of practices like phonography and field recording, sonic naturalism has been identified as typical of ecological and perceptual models of listening (de Seta, 2021). With this essay, we aim at sketching out two specific models of sonic communication that transcend naturalist realism by establishing contact with the supernatural through practices of listening and channeling. We call these two models hypernaturalism and ultranaturalism. Through this contact between the supernatural forces of spirits and ghosts and the material properties of audio signals and equipment, the two models channel the invisible into frequencies—the rate per second of a vibration constituting a sound wave and electromagnetic fields—and transpose it onto the audible spectrum. Even though hypernaturalism and ultranaturalism share the same goal—to make the supernatural audible to human listeners in some form—the two models do so in radically divergent (and, we we argue, almost entirely opposite) ways, which in turn reveal profoundly different conceptions of mediation and techno-sonic imaginaries.

This is due to the fact that while sonic artifacts like recordings can indeed convey accurate representational information through a documentarian approach, when such artifacts are used to extract argumentative loopholes, theoretical uncertainties and ambiguous episodes act as lines of flight to reflect on how sonic encounters with spirits and audio infrastructures patch together reflections on neglected or silent mediators and mediations. For us, using audio as a dowsing practice to move forward towards the unknown of the heard—or the unheard, in Ewe’s words (2021)—is to employ the ear as a surveillance device for picking up sonic traces of sonic cryptids and otherwordly entities. Here, the real question is: what is this listening we are experiencing? What is it doing? Our argument here is that using recordings as compasses resembles what Stanisław Lem has written in Golem XIV: “The meaning of the transmitter is the trans-mission. The meaning of the transmission is the trans-mitter.” When it comes to this kind of audio quests, we realize that, whether we’re trying to tune into radio frequencies, charred landscapes or spirits’ sounds, only accidents are real. Unnaturalist listening requires the listener to put themselves in the position to experience an accident.

Faraday Traps: Hypernaturalist conjurings

«…most peculiar occurrence which I feel compelled to document, though I doubt Mr. Marconi will give it much consideration. As you know, on the 12th inst., we received […] our colleagues in Newfoundland. What troubles me, however, is the extraneous signal […] Mr. Marconi dismissed as mere atmospheric disturbance or instrument malfunction. Upon reviewing the tape recordings, I observed a series of pulses that do not conform to any known telegraphic pattern. The irregular cadence cont[ained?] […] [I tran?]scribed: “…ANK-SUMPT…15…” followed by a series of rapid pulses that defied interpretation, and a repeated pattern of sounds I could only approximate as “E V P” and “TEST”. Mr. Marconi insists this is merely the result of electrom[agnetic?] […] me to excise this anomalous segment from our official records, concerned it might undermine the credibility of our achievement. […]»—Endicott, 1902. “Personal Correspondence from Poldhu Wireless Station.” In Marconi’s Early Transmissions: A Collection of Primary Documents, ed. Arthur L. Thompson. London: Institute of Electrical Engineers, 1967. [1]

Our aim was to test different registers of audio encoding/decoding of communications to probe the boundaries of unnaturalist audio research. This included iterating hypernaturalist and ultranaturalist sounding and listening experiments to understand which types of ethnographic exploration of the audio would lead to which results. Therefore, before reporting further regarding the results of our investigation, let’s examine a possible framing of these modes of supernatural encoding/decoding.

Let’s begin with hypernaturalism, which today finds widespread appeal among new millennium ghost hunters. On the one hand, ghost hunters follow a naturalistic posture betraying an audiophiliac faith in the transparency of the technological medium (i.e. the Spirit Boxes / frequency scanners). By pushing naturalism towards the hyperreal imaginary of high-quality recording and capture which allows to zoom into detail and uncover ghostly presences, their ontology of mediation posits technology as an infrastructure for a sort of supernatural surveillance which treats invisible entities as things to be located in space. On the other end of the spectrum, we have ultranaturalism, which can be found among Sundanese performers and audiences. In Sundanese tarawangsa, the technological apparatus (i.e. the audio recorder) works in a way much closer to a prosthesis and extension, opening worldwide channels of communication between humans and spirits, thus empowering the latter category through a transfer of agency: other technologies of tarawangsa—musical instruments, and the music itself—benefit from the sought-after transparency of HD recording and playback to activate supernatural processes. By following these two models to their extreme, this text compares two approaches to decoding supernatural audio signals through systems of transmitting and receiving technologies, and theorizes the overarching history of how both technological advancement and capitalist disenchantment have consistently sought to encroach upon to the afterlife, the supernatural, and other invisible worlds through forms of control over signal and noise, all the while practices like mediumship, paranormal phenomena or altered states of consciousness have wrestled against this process of neoliberal assimilation and technological reterritorialization.

The relationship between audio technology and the supernatural—and specifically, the world of the dead—has been a constant topic of exploration and speculation which contributed to new technological auscultation and communication systems. Since the middle-ages, the invisibility of sound has been correlated with domains of existence beyond the visible, and linked to uncanny phenomena or more-than-human powers. In many cases, the impossibility of recognising a sound or its source has been linked to fantastical or supernatural beings like goblins, ghosts and witches. The invention of telegraphy, and those of many other sonic technologies after it, have only strengthened the relationship between sound and the invisible, as the inherent uncanniness of an audio signal coming from an invisible, unidentifiable source remains a constant challenge to visualist epistemologies.

Counterintuitively, the history of technological development has not extended disenchantment to the realm of sound – rather, it has opened up new pathways for the supernatural. This history could be argued to begin with three raps at the Fox family’s modest cottage in Hydesville, near Rochester, New York. In 1848, during what became known as the Rochester Rappings, the family’s sleep was disturbed by strange banging noises. Kate and Margeretta Fox replicated the sounds they heard, eliciting three unexplained raps as an apparent response. The spirit realm responded to the sisters’ questions through a “celestial cypher”: knock once for “yes” and twice for “no” (three knocks allegedly implied ‘don’t know’). According to Jeffrey Sconce’s Haunted Media: «with this exchange of words and knocks Kate Fox had opened a “telegraph line” to another world, a wireless’ spiritual telegraph». What’s remarkable in this episode is that the first appearance of a signal-based system of communication between the natural-human and supernatural-ghostly occurs after the creation of the telegraph, and is referred to as “spiritual telegraphy.”

Similarly to Marconi’s episode described in the intro, in 1920, Thomas Edison—inventor of another audio technology of communication across distance, the telephone—attempted to develop a “spirit catcher”: a recording device that could capture the voices of the dead by harvesting their sonic traces. These episodes are more than anecdotal: they demonstrate that since the beginning of audio technologies, the drive to detect, interact, or capture unseen, spiritual and supernatural forces, has been central to technological development, and always accompanied by the potential for self-deception through tricks of the human capacity for sonic imagination.

If these first attempts showed the possibility for audio technology to tap into signals sent from either spiritual presences in physical geographical locations or from the more-than-human realms such as the heavens or the underworld, it is with EVP (Electronic Voice Phenomena) that signal-based supernatural communication becomes consistently theorized. In 1959, while making a cassette recording of a Chaffinch singing in his yard, Freideric Jurgenson unintentionally picked up his deceased father’s voice, which only became audible when the audio was reproduced. These spirit voices, which Freideric Jurgenson and his disciple Konstantin Raudive picked up in their field recordings of empty rooms, actually expressed a preference for communicating via radio frequencies. Owing to their purportedly “ethereal” characteristics, spirits have frequently been pursued on the radio frequency spectrum by creating some form of feedback between various forms of transduction.

Two things become apparent from this history: the first is that new technological means of wireless communication were not just seen as something that compatible with the dead, but also quite familiar to them. It would not be surprising if this ontological correlation between ghosts, spirits and the supernatural with radio frequencies was not only linked to the naturalized connection between voice and the divine, but also reinforced by the coeval cult of electricity: an invisible, mysterious force that could be trapped and capitalized on for the first time. In this context, the “objectively” efficient and scientific approach of transducing audio messages through a division between signal and noise led Raudive to imagine actual afterlife infrastructures of communication operating through a parallel system of ghost radio stations. What is relevant to the present argument is that humans and ghosts communicate through identical physical principles and technological infrastructures. The only difference being that, ominously, it is humans who have to decide to open this channel and scan for signals.

The most recent step in this long history of supernatural communication through audio technology is exemplified by the Spirit Box. In 2002, Frank Sumption, an EVP enthusiast, said that after receiving design instructions from the spirit realm, he managed to build a gadget enabling real-time contact with the dead. The box, similar to a portable radio, is characterized as a hybrid white noise generator and an AM radio receiver modified to sweep back and forth across the AM frequency spectrum, choosing split-second sound snippets. Spirits are thought to communicate across various radio frequencies, so Spirit Boxes provide a platform for them to speak out. Typically, one will ask the spirits a question. If they are present and willing to communicate, they will engage with Spirit Boxes by momentarily stopping the sweep on one radio station to allow the human listener to hear a specific word or phrase. Again, this demonstrates how agency in supernatural communication through audio devices is mainly human-centered and its purpose functional: receiving answers. Digital audio technology, in this case, is the main mediator between humans and spirits, who have only one thing left to do: interfering with the gadget’s frequency sweep.

As the book P-Sb7 Spirit box Research for use in Inter- Dimensional Contact by ESP researchers J.P. Moss and H.R. Ashbury explains, the Raudive diode allows the modulation of frequencies to actually modulate the modulation themselves, a mechanism which incrementally obtains faster, humanly imperceptible sweeps, able to reach these ghost frequencies only tangentially touching the FM spectrum. Such modulation allows this shift onto these supernatural bands of transmission.

A common thread woven through all these historical examples as well as in Tellurian Drama, is that technological advancement in the realm of telecommunications has consistently developed alongside the demands of warfare, colonialism and imperial domination. The capability to force—or at least nudge—the invisible to reveal itself is a much sought after form of power. We can see this logic in most examples of communication with the more-than-human through audio signals and technologies such as frequency filtering or scanning. When drawn into this kind of assemblages, spirits undergo a drastic reduction of their agency, which is limited to the possibility of responding to a signal or answering a question through a rather narrow set of pre-established formats: raps on walls, unclear utterances, technical interferences. The spirit’s communicative act is consistently treated as an incomplete attempt, a snippet of audio detritus to be made understandable through technological processing and, eventually, useful for human interpretation. Given this strict agential framework, it is not surprising that many instances of spirit communication are counterbalanced by cases of refusal, in which the spirit does not fall into the power of technology. The vast lore developing around spirits evading the revealing power of all-seeing (and all-hearing) technological devices offers a clear illustration of the hypernaturalist ethos of capture shared by paranormal researchers and spirit hunters, which refusal seeks to counteract. If agency is stacked on the human side of the equation, leaving the spirit with only limited room for frequency intervention, a refusal to engage and a retreat into the unnatural seem like appropriate responses.

Duppy strings: ultranaturalist escapes

«The celebrated Mr. Daniel Dunglas Home, whose remarkable abilities have been demonstrated before crowned heads throughout Europe, presented a display of such unusual character that it merits particular attention from serious-minded inquirers into the mysteries that lie beyond our present understanding.

During a private séance conducted in Lord Brougham’s library, an accordion was placed upon a mahogany table, whereupon—according to multiple reliable witnesses—the instrument began to “breathe” as though animated by an unseen presence. What followed, as described by Mr. Home himself, surpasses the usual manifestations attributed to his uncommon gifts.

“The accordion expanded and contracted in perfect simulation of human respiration,” Mr. Home informed our correspondent. Most remarkable was Mr. Home’s assertion that the sounds resolved themselves into fragments of human speech: “It repeatedly uttered what appeared to be a name—‘Miss Mou Naur Wan’ or similar construction—and spoke of ‘frequencies’ and ‘earth vibrations’ in a most perplexing fashion.”»

—Anonymous, 1859. “Remarkable Occurrence at Lord Brougham’s Residence: MR D. D. Home and the Speaking Accordion”, The Caledonian Mercury, 19 October.

In contrast to ghost scanning and other forms of audio surveillance of the more-than-human, which are based on an fixation to make the invisible audible and which we have called hypernaturalism, the spirit mediumship augmented by audio technologies that can be found in music-mediated supernatural communication reveals another way of tuning oneself into the spirit world, which we connect to a very different, ultranaturalist, model of listening.

In the tarawangsa ritual, typically held for the yearly harvesting ceremonies in the hills of the Sumedang regency, near Bandung, each role is rigorously organized and co-related with each other in order to allow the event, which can last for days with only a few hours of silence everyday. The tarawangsa and jentreng make the ritual location an hotspot for spirits by working as the emanation point from which the melodies – codes to invite the spirits—diffuse in the area, broadcasted throughout the village thanks to a wired system of speakers. In the tarawangsa event, particularly, the saehu, the spirit master leading the ceremony, mediates between the possessed/spirit and their relatives when the former delivers the latter messages. Sometimes, during the dance that ensues with the music and which works as a means to facilitate possession through the gathering of energies in one’s own moving body, the messages delivered by the spirits can be unpleasant. Those must nevertheless be conveyed to the concerned person or to the audience in the best way possible, so that good intentions can be sent in a positive way, despite any bad news being delivered. It’s all a matter of how this message is encoded and decoded through this human actor. In fact, despite in a light, convivial way, this phase of the ceremony is always loaded with a certain amount of tension and sadness.

Additionally to the saheu, another figure is also pivotal to a tarawangsa event: the key keeper. The juru kunci is the individual responsible for opening spiritual communication. He sits cross-legged beside the parukuyan (a clay container where charcoal is used to burn incense for the ancestors) both during the preparation and the performance. He must know the moments when it is time to burn the incense, so that communication and the nuances of the sacred can be strongly maintained during the event and its progress. While in terms of transmission and reception the saehu manages the transduction and delivery of messages, the juru kunci makes sure that the channel of communication through which music flows to call the ancestors, activating their capability to reach the human world to deliver their communications.

If the juru kunci is capable and the musicians proficient enough, the area where the performance takes place is literally filled with power and becomes a gathering of spirits and humans, amplified by audio reproduction technologies throughout the village, thus extending its range. The music, the invocations pronounced by the saehu and the offerings made to the ancestors before the show are always placed in front of the musicians and must be carefully prepared.

During possession, music causes both (a) the interest of the spirit/ancestor in participating in the performance by taking the control of a body and, (b) the emotional overdrive of the human host leading to “uniting with the spirit”: nyurup. The emotional climax that brings together human and spirit—instantiated as possession—happens because of one’s soul resonating with the music’s frequency. This is not a physicalist explanation invoking resonance or sympathy. Whereas musical resonance is the phenomenon for which «a particle is subjected to an oscillating influence (such as an electromagnetic field) of such a frequency that a transfer of energy occurs or reaches a maximum, possession happens, instead, because of genealogical, geographical and kinship relations. As local theories argue, specific arrangements of organized sound (rhythmic patterns, harmonic progressions, tunings, melodic structures) that are related to someone’s ancestors can connect with the person’s soul and affect it until it ‘becomes one’ with the spirit.

Here the mention of audio diffusion throughout the village emphasizes how the ultranaturalist approach of tarawangsa does not idealize the liveness of performance versus its phonographic capture and reproduction: the only concern is with achieving a high enough quality and reach so that the spiritually important component of music and its tuning is not misrepresented. If the tuning is correctly captured, a tarawangsa performance can match a certain “soul frequency” (frekuensi jiwa) and cause possession. Through possession, the human body becomes both the receiver and the transmitter of the spirits’s messages and agency, mediated by the facilitation of the saehu and juru kunci. Spiritual communication during tarawangsa possession typically includes reassurances that one’s relative is happy in the afterlife, recommendations of various kinds and, occasionally, even predictions and warnings. This sort of communication is framed in a larger system of exchange with the ancestors during which they are honored through gifts for the protection that they continuously grant to the community. Communication flows in both ways, and every participant is allowed to take the role of transmitter or receiver. Once the ancestors feel satisfied, they ask to go ‘back home’ (pulang/uih) to the alam gaib, the invisible world inhabited by the spirits. An exorcism is carried out, and the human host returns to consciousness, usually forgetting every detail of the experience.

Let us repeat our main argument here: in Sundanese spirit ceremonies, music is itself a technology, and its performance has a quite practical and defined outcome resulting from its use of ancestral frequencies and tunings: possession. But for the purpose of our essay, what interests us is how digital AV technologies also play a part in this outcome, as not only live performances but also recordings of tarawangsa performances can cause the possession of the listener or spectator. And even more interestingly, what makes spirit possession possible through recordings is the quality of the audio: a proper musical performance—proper in the sense of both being executed without errors and being connected to the ancestors—when reproduced by a high-fidelity audio recording, honors the spirits, and thereby leads to possession. In this specific case, for music as a technology to successfully connect humans and supernatural entities, a sufficiently high-quality recording and playback infrastructure is necessary to transduce the performance’s sonic elements: intonation, dynamics, tuning and rhythmic patterns, as well as the overall musical style of the ensemble.

In this sense, audio recording technologies are conceived in a radically different way than those of ghost hunters: not as devices playing the role of receiver and transmitted through feedback loops intensifying frequency inputs and outputs—rather, they are utilized as repeaters and range amplifiers for spirit frequencies and their ancestral tunings. Both groups—ghost hunters and tarawangsa performers—push audio naturalism into unnatural domains while keeping its epistemological predilection for sonic realism. But in one case, audio quality is the canvas that allows ghosts to manifest through interference; in the other, quality is necessary for the channeling of proper frequencies attuned to the ancestors. Going back to Rizaldi’s speculative analysis of radio Malabar, we could say that the agential power of spirits decreases as distance from their place of origin and belonging (the forest hamlet, the village, the mountain) increases. So, while it is true that music as technology is enough to cause spirit possession, recording and playback technologies are necessary to sustain and strengthen the reach and efficacy of this channeling process through sound reproduction (the possibility to listen to the music in different places at the same or different times), distribution (digital repositories and archives) and circulation (social media and digital sound devices). Thanks to high-definition audio, these technological media are capable of pulling together the assemblage of tarawangsa activities (performance, listening, etc.), making possessions possible even thousands of kilometers from the musicians’ geographical origin and the spirits’ dwelling place.

In tarawangsa and similar models of possession practices, the basic ontology of communication and interaction between human and non-human agents is configured as a system of horizontal encounters and open-ended dialogical exchanges. While in the case of ghost hunters supernatural entities are only expected to respond or refuse to engage in a transactional communication initiated by humans, in tarawangsa the body of the host itself is offered as a receiver and transmitter of the ancestor’s agency. For ghost hunters, audio technology opens up communication channels through processing routines like noise reduction, signal decoding or spectrum sweeping, for tarawangsa performers audio technologies are an amplifying prosthesis and a range extender, not a conditio sine qua non for spirit communication. In the first case, the possibility of communication with supernatural entities is premised on both the epistemological symmetry between human and more-than-human mediation and on the revelatory power of noise management. In the second case, music is itself the technology through which a human body becomes the communication medium, and signal processing can help sustain this process. It is not by chance that in EVP frequency spectrum scanning, listening to the spirit world depends entirely on fetching for snippets of voices amidst the audio debris of white noise generators, dead air and empty radio frequencies; vocal intelligibility emerges from a process of refinement and purification of the signal. Conversely, in tarawangsa, human-spirit communication is lossless, first because it comes directly from the ancestor through the human host’s body, and secondly because it is remediated through the high-fidelity vector of sound recording technology.

At this point, it is important to note that the Sundanese human-spirit communication system relying on tuning and frequency is not native to the archipelago. As a matter of fact, the word “frekuensi”(frequency) itself is a rather recent addition to the Indonesian language, a clear semantic loan from a foreign technical vocabulary indexing the influence of Western scientific development and “modernist” ideologies of technology on local ontologies. What is interesting in the case of tarawangsa is that even a technical concept like frequency, with its aura of material mechanicism and quantification, can be deployed by two groups as a component of diametrically opposed models of the supernatural. Spirit mediumship and music-caused possession have existed across the globe long before the emergence of modern audio technologies: with the introduction of devices like radios, amplifiers and recorders, the naturalist ideology of objectivity that accompanied their global journeys has been spun into very different models of listening. Our sketch of a comparison between ghost hunters and tarawangsa performers illustrates how two of these models incorporate audio naturalism in their approach to the supernatural, reconfiguring concepts such as interference, fidelity and quality for their own practical purposes: talking to ghosts or channeling spirits.

Black Boxes: mapping ghostly fields

“The conceptualization of this particular arrangement came to me during a trance-like state in autumn 1965. While half-dreaming, I perceived a series of seven distinct tones—later identified as precisely matching the scale of 438 Hz, 526 Hz, and 614 Hz. Most remarkable was the final tone which resonated at exactly 564.3 Hz—the precise frequency at which germanium’s crystalline lattice achieves maximum electron tunneling efficiency. In this altered state, I witnessed a figure moving hands above invisible strings, eyes rolled upward showing only whites, body trembling as if conducting energies rather than merely performing. The vision conveyed with unmistakable clarity that element 32, with its unique four-electron outer shell configuration, was the singular material capable of bridging the electromagnetic divide.”—Raudive, K., 1968. The Raudive Diode Receiver: Instructions for Reception of Voices from Beyond the Physical Spectrum (Revised Edition). [2]

Both of these examples problematize the assumption that audio naturalism is necessarily correlated to the “metaphysics of presence.” In spirit hunting, the role of signal opacity is subverted and reconfigured as a naturalist reterritorialization of the supernatural: the otherworldly domain of ghosts is imagined to function according to the same physical principles of the world of the living. In looking for presences beyond the metaphysical world, frequency scanners take the residual interferences caused by signal loss and quality degradation (hiss, static, hum) and focus on them as puzzle pieces to be demodulated into clear snippets of communication. We call this model hypernaturalism: an approach to the supernatural that extends naturalistic ideologies of sound into the more-than-human by assuming that corresponding analytical categories can be translated one-to-one. In this sense, it is not surprising that the hypernaturalist emphasis on the signal-to-noise ratio, on the transduction of interference into messages and on the capture of evidence maps neatly onto the empirical fixation on proving that ghosts are, in fact, real.

In opposition, tarawangsa exemplifies what we call ultranaturalism. Just like ghost hunters, tarawangsa musicians are also seduced by the allure of high-fidelity audio, operating under the assumption that a high-quality recording of a performance is capable of not only perfectly reproducing music, but also of channeling the power of supernatural entities. Their audio naturalism pushes realism in another direction: that of efficacy. Differently than in dub music, where the term “dub” echoes both the duppy—the floating ghost of Jamaican cultures—and the dubbing process leading to a spectral audio doppelgänger which is similar but other from its original version, tarawangsa’s audio replicas are assumed to be identical (or as close as possible) to their live execution. But in contrast to the audio naturalist’s fixation, this fidelity is not sought after for the human listener: it is the very condition of possibility for channeling spirit possession. If a recording is of sufficient quality to reproduce the frequencies and tunings accurately enough, listeners are transformed into receivers and transmitters, extending the reach of the spirit world into the human one. In contrast to ghost hunters, here the fixation on realism is a means for the more-than-human to encroach upon the human. Audio technologies are not necessary for communicating with spirits, since music and human bodies are already enough—all it can contribute is an expansion of this communication’s reach in space and time.

In the 19th century, scientists postulated the existence of the ether: a universal substance which acted as the medium for both the transmission of electromagnetic waves and the existence of invisible entities. Newton argued that only an undetectable medium like ether could explain “remote action,” or the influence of an object on another at a distance—encompassing planets, radio waves, or poltergeists. The functions of ether extended to consciousness, which was theorized to be made up of unseen yet tangible vibrations radiating from the brain into a diffusion medium. And when it comes to colonial writer Rudyard Kipling’s 1904 short story Wireless, a key theme is the unpredictable, unexplainable mixing of the spiritual and material, which is precipitated by the development and use of radio and wireless technologies. This argument for remote action reflects a belief in an overlap between the capacities of radio frequencies, brain waves and spiritual entities—a model of communication that resonates with the relational assemblages of humans, spirits and technologies expressed by tarawangsa. In the story, the Morse code radio channels and amplifies exchanges already happening between humans and spirits. From Rizaldi’s Tellurian Drama to Kiping’s Wireless, and from ghost hunters to tarawangsa musicians, we have been concerned with mapping the shifting relationship between the natural and the supernatural as it is shaped and reconfigured by different forms of technological mediation.

As we hope to have demonstrated, the prevalence of sonic naturalism—the assumption that sound constitutes a somewhat transparent form of mediation and that high-fidelity reproduction allows to reproduce reality to a certain extent—does not necessarily correlate to a specific relationship to the more-than-human. In fact, the two examples we discuss in this chapter exemplify two diverging, and perhaps opposite trajectories of audio naturalism as it is confronted with the supernatural. We have called these hypernaturalism and ultranaturalism, and we maintain that these are not mere reflections of temporal or geographical differences: rather than past/future or East/West divides, we want to draw attention to how sonic epistemologies are constantly made and unmade. The surveillance epistemology underpinning EVP scanning and ghost hunting is not the only possible way of approaching the supernatural through audio technologies; as tarawangsa demonstrates, music can in itself be a technology, the listener can become a channel, and audio devices can become spirit prostheses. This essay offers a speculative provocation: much more work in comparing models of listening beyond sonic naturalism and human-centered listening will be needed to further deconstruct both the metaphysics of presence in audio as well as more ontological distinctions between concepts such as sound, noise, or signal.

Spirit mediums, spirit media

In the case of both ghost hunters and tarawangsa players, human decoding practices of the supernatural intersect with audio recording technologies. But while in tarawangsa’s ultranaturalism diffusion and circulation through speakers and recordings is accompanied by the authority and expertise of human spirit mediums allowing communication to flow—the juru kunci’s channel/line management—and be delivered correctly—the saehu’s overseeing of the messages’ delivery—hypernaturalist ghost hunters are left with the company of audio artifacts of difficult interpretation as that may contain/represent/decode communication from supernatural actors, or just a bunch of chopped, inconsequential, semi-verbal sound bites.

With their array of signal-noise optimisation hardwares and softwares, ghost hunters are left alone with only a pile of recordings, their spirit media. The documentarian mentality, interpreting recording as a trap for an acoustic objective reality, a means of capture based on a naturalist interpretation of the audible, allows ghost hunters to believe that the sounds coming out of the Spirit Box can be understood as intelligible, self-evident, verbal communication which the recording demonstrates. This logic is only possible if one assumes that audio recording technologies can themselves be authoritative without the necessity of an interpreter—a medium—thus becoming the sole transmitter/receiver and encoder/decoder device needed. Conversely, in tarawangsa, while recording and audio reproduction hardware is used to expand reach and propagate signal, almost as a repeater, approximation of transduction is always checked-upon by human mediators, which remain the main transmitters/receivers and encoder/decoders.

Issues of power and democratisation aside, these examples hint at the core difference between spirit mediums and spirit media: how they attend to uncertainty and how they deal with authority in audio mediation practices. While ghost hunters’ pretense of the self-sufficiency of audio technologies interpreted as actual pieces of information seems clear cut, our argument is that, while spirit mediums rely on their authority, their knowledge and interpretation of such communicative processes, spirit media are valuable precisely because they don’t hold nor assert any authority on the representation and content of supernatural audio messages. Let’s consider Shadow Box, Monteanni & tarawangsawelas’ composition as an experiment employing audio to prove such an argument. By presenting these questions at the project’s core:

What if the spirits felt invited to listen and follow the music instead of replying to our closed and limited questions by means of stuttering vocal messages? What if communications from beyond, from the other side of the AM/FM white noise, metonymically the threshold of life and death, are more similar to lo-fi, bitcrushed polytimbric soundscapes full of bitrate reduction artifacts and electroacoustic short-circuits rather than shards and splinters of (in)coherent thought? These are all questions which the piece brings to life in one’s ears.

The musicians try to hijack the Spirit Box’s logocentrism through another musical technology believed to call on spirits, the tarawangsa. Although these two processes are self-sufficient and are never combined, nothing forbids one to do so, as the ideologies on spirits communication are not developed to conceive of the other practice on both sides. Additionally, considering how radio transmissions work, and believing the central theories that spirits have their own radios, or, if nothing else, communication systems compatible with the ones of radio, we can speculate that nothing would technically stop music from coming in or out of the box. When we shift the task from decoding noise into verbal signals to considering any type of signal as potentially sounded by the other side and then lost in the process of transduction, we lose track of the result of decoding: we don’t know if the recording discloses music, sound and words emitted by actual ghosts or just asemic noise. In exchange, we discover an entire process of listening. In creating and listening to spirit media, we explore this process of decoding uncharted fields, while accepting that the output is the equivalent of an aural black box.

Going back to the possibility of representational, objective authority for spirit media argued by ghost hunters, as the plurimus disputes over actual intelligibility and meaning of EVP recordings show, such artifacts remain opaque traces of the passage of something undecoded, of processes of emergence of unclear and uncanny communications amidst dead channels and impossible interferences. Something that Shadow Box only dramatizes. What we are left with, is the persistence of something that stays unresolved and suspended in the borderzone between our categories of natural and supernatural.

In a record called The shell that speaks the sea, by David Toop and Lawrence English, edited on the label Room40, the authors describe their mesh of field recordings as “the affective realm that haunts, rather than describes, experience.” As The Quietus Journalist Daryl Worthington underlines in an article about the work, it’s worth pausing on this word, “haunts,” for a moment. Alongside its paranormal connotations, haunting also evokes persistence. A recurring of something ungraspable but resolutely present. A presence that can’t be quantified but affects the working of the mind and mood. Following this feeling, we too have tried to use audio as a tool of reconfiguration and remapping of space, not only of (impossible) documentation but a way to test our assumptions on what we mean by objective reality.

Overall, our tests and researches revealed a double persistence: the one of letting things (spirits) speak for themselves as well as the one of taking the responsibility of becoming ourselves decoders for something that speaks: mediums. Particularly, we believe that precisely this incapability of deciding, this opacity emerging from our encoding and decoding devices, our spirit media, is part of this haunting: something unrelatable we are obliged to relate with when putting ourselves in the position of experiencing an accident, something we could not forecast. The point for future audio research into the world of the un/natural seems to stay with these hauntings. Hauntings of problems that persist.

In the meantime, we have to keep in mind that understanding how we listen to the more-than-human and how the more-than-human listens back to us—through topographical features, technological infrastructures, spiritual frequencies, supernatural tunings, and much more, can shed light (or, perhaps, dispel the silence) around yet uncharted depths of our own all too human auscultations. Revelling in these conundrums, for some reason we could not stop thinking about something that David Bodanis, author of Electric Universe: The Shocking True Story of Electricity, has written to explain how frequencies and radio communication pass through us, ignoring the physical world: “To radio waves, we are ghosts.”

[1] Discovered among private papers of the Endicott family and published posthumously. Authenticity confirmed by handwriting analysis and contextual references. Original letter fragment preserved in the Science Museum Archives, London. Catalog reference: SM-MRC-1901-046E].

[2] Baden: Psychic Audio-Visual Research Institute. [Translated from German by Hans Geisler. Private publication. Pages 17-18. Original manuscript held in the Latvian National Archives, Riga. Document reference: LNA.RD-EVP.1968.C14].