Stacy after Pier Paolo

On Stacy Szymaszek’s “The Pasolini Book”

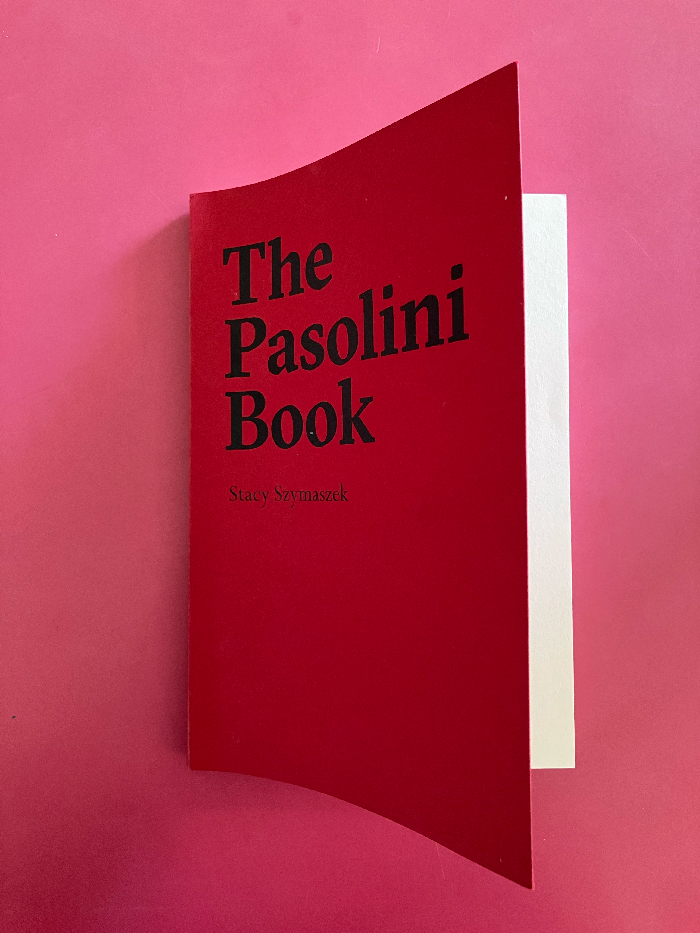

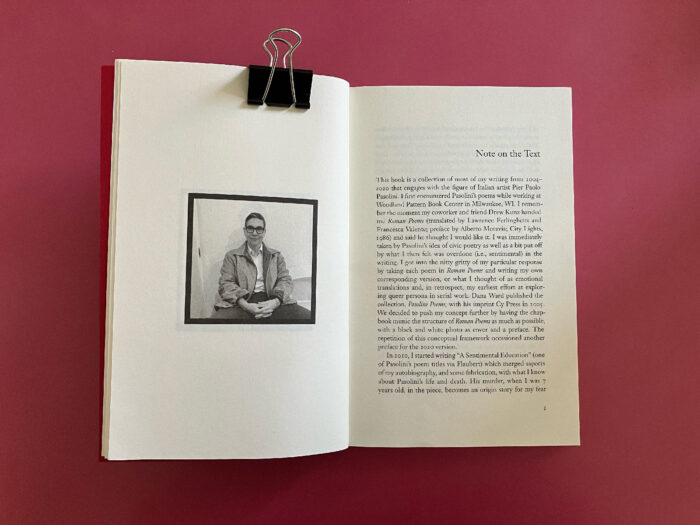

In the middle of this incredibly hot summer, poet Stacy Szymaszek contacted me to ask if I wanted to review her new book The Pasolini Book which “documents her engagement with the work of the Italian film director, poet, and political figure Pier Paolo Pasolini alongside her own evolving vocation as civic poet and dissenting subject within an American polis by turns hostile and hospitable.” For the 100th anniversary of Pasolini’s birth, she wanted to get it out in Italy, since for contingent reasons she never managed to come to Rome to finish her book as she wished, and eventually none of the poems were written in Italy. I am very glad I got the chance to write about it.

I have to thank Allison Grimaldi Donahue for putting me and Stacy in touch, for thinking about me in the first place and for her (always) precious feedback.

How does a book grow over somebody’s shoulder, of she who wrote it, and he who inspired it, how does it glue both shoulders together by means of the images that it causes, of two people meeting in times which are non-coinciding, yet on a level where they physically meet and hug and rest their head over each other’s shoulder, as if they were friends. Well, if you ask me, that’s what writing is for—sometimes and most of the time writing is the bridge over the water of desire, it compensates over any misalignment, be it time-based, space related or due to overwhelming feelings. In science and in fiction, writing allows we who write to reconcile with those and that we’re thinking of. In poetry, it takes us a little deeper and closer—as far as borrowing someone’s voice, for it to stem and grow over our shoulders, until head to head we feel our own tone merging with the others—like we would say the same thing at the same time, I can drift into something that feels more spiritual than a tribute, if I ought to explain it, that would feel like myself transmuting into a vessel where the other voice finds shelter and amplifies. An echo before utterance.

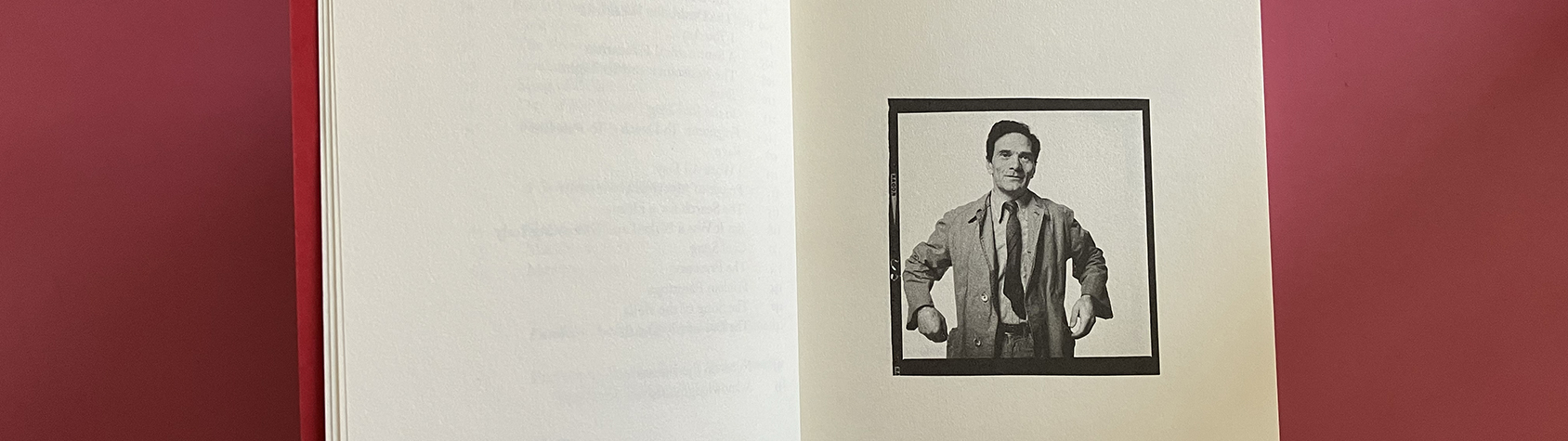

Stacy Szymaszek’s The Pasolini Book seems to come out as such, after over fifteen years of fermentation, a collection of poems grew into a book, where a name remains as a keepsake for its intention, and for, on the one hand a sense of gratitude, and on the other to hold something that feels like a desire for an impossible encounter—that can only happen through literature. Yet Stacy stays with Pier Paolo, insists on him, like a mourner who’s left to write odes to the departed. Pier Paolo is no unknown soldier. Since his death, his legacy has never ceased to root beneath the vast terrain where politics, literature and images breed their strains jointly. It is recurrent, and there’s so much to unravel, so much was produced, that those who start digging are caught in awe, with so many details to describe and so many stories to tell, between the public and the personal, so many lines to quote and images to propose, it never stops—it is still multiplying. Pier Paolo’s voice is entangled in this very same rhizomatic effect (or affect if we will) where he ends up inhabiting other bodies, becoming a poem that becomes a book, or a dance piece. Isn’t it wonderful? Such a fertile afterlife.

Stacy remains with Pier Paolo to declare herself a civic poet. She holds him as “empathetic companion” in her “anti-institutional, anti-authoritarian stance” yet she keeps the first person. At times it’s Pier Paolo resounding in her words, at times it’s Stacy maneuvering Pier Paolo to prove her point. In this overlapping, there’s a clear asynchrony, as well as an insurmountable distance in space, and we do feel the jet-lag. It was uncanny for me to read this in Rome, where I am based—since in this book, the city is perceptibly one end of the means, a craved destination, and perhaps a character on its own, but mainly a location and backdrop of most of Pier Paolo’s history, a landscape to his figure. And while Stacy stays with Pier Paolo, she’s clearly somewhere else, walking on another terrain, yet embodying very similar struggles, inhabiting analogous words. Indeed, she’s in Milwaukee, then she’s in New York City, and from there lingers over his history as if it would be a place she knows. Well, there’s something about Rome, that makes me imagine it as it was in the 70s—something that never changes, and something about it that gives a false impression of what she actually is (the city is clearly a she), her essence is disguised under the whole halo of (neo)classicism downtown. We who live in the outskirts, don’t buy that—those all become ruins merging with what’s contemporary, which is not always as planned nor as pleasing. Let’s say it’s such a mess that the figure struggles to recognize itself in that landscape.

I guess there was such a feeling in Pier Paolo’s life and oeuvre, so much so that his characters were so obsessively detailed to become almost allegorical. In science and in fiction that’s what writing allows—exaggeration and precision, while in poetry it’s a matter of time—whereas an instant gets magnified in suspension. In The Pasolini Book, Rome and reality are indeed suspended in Stacy’s memory of it—a non-phenomenological experience driven by the desire to remember everything of a life that is made of two, that is lived by two bodies in two different fragments of a linear vector of time. When he dies, she doesn’t know—only later will she value the relevance of that specific event, she’ll come back to mourn and celebrate that life, she’ll borrow his moves and return to those places to become that man. This is what writing can do—because writing doesn’t fear time. We can return wherever, to any moment. That’s also how we constantly return to ourselves, and to get there we need to cross through other selves and other bodies, as if they were thresholds they lend us words we lack to express our politics, ground to land on, a mirror where we see our image, and a compass to foretell our future. Writing is always intrinsically a collective endeavor. In this book, Stacy uses Pier Paolo to write herself down. She rewrites Pier Paolo and redirects his tone towards her urges.

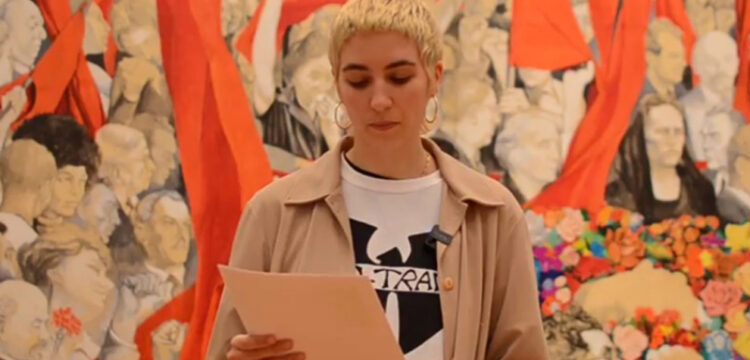

I too have an overlap—seemingly insignificant. The last part of the book is titled Pasolini Poems :: Divina Mimesis which was written in 2020. When I was still a student in 2016, I used to carry the book with me, a Mondadori edition from 2006, with a photo of an anti-government demonstration on the cover. That copy got as far as Tehran where I read a paragraph out loud (in Italian) somewhere over a footbridge not far from Enghelab Street, where now as I write our sisters are enduring a revolution for more than three weeks. As far as I can remember this was the passage:

“It wasn’t hard for me to realize that in reality all those people, along the streets of their world of clerks, professionals, workers, political parasites, petty intellectuals, really were running like madmen behind a flag. Through medieval alleys, or along great bureaucratic arid liberty-style streets, or, finally, through the new residential popular districts, they didn’t just drag themselves around— as it seemed—through the orgasm of traffic or of their duties: but ran behind that flag. It really was little more than a rag, that flapped and roiled obtusely in the wind. But, like all flags, it had a symbol drawn, in its center, discolored. I looked closer, and didn’t take long to notice that that symbol consisted of nothing other than a Shit.”

I think this is the closest I got to Pier Paolo, or better to say, this the deepest manifestation of Pier Paolo’s work inhabiting me, as it were him borrowing my body to say something out loud in that specific spot, to be in that geography, to repeat what he wrote, to simply return, or perhaps to take me back to that moment today.

“summon to mind our last few years

without price and before any

of our time was extracted from us

when we wrote in our diaries

then our diaries became poetry

that announced our spirited day to day

hurling shoes into the gut of their perverse logic

see young citizens coming together election week

learning how to care for bullet wounds

the week virus cases break the global daily record

never lulled into a false state of trust

they are naturally ready

to correspond with us”

This excerpt of Stacy’s Civil Song carries indeed the correspondence occurring among voices and bodies living different historical times in seemingly far away areas. It could have been me, somewhere else, yet it’s she who lives in her times and feels the space as it is around her. So, it was him not long ago digging out before his grave planting seeds that could stem and grow over many other shoulders, to carry his voice and turn it into a choir, a place, a city where poets will read out loud and balm the air with the smell of jasmine. We all find ourselves as “us” in this role and responsibility of the civil poet, as someone who ultimately writes from and for the ordinary—and always holds a very specific role within a community. I personally see this aspect as a necessity, for once to feel whatever we are as ordinary and most of all to be able to survive and thrive only within a kind of sharing that holds us and doesn’t require us to constantly prove our worth—the world outside does enough of this. This sense of entitlement to just be and become who we are is a communal experience, and there where we feel safe and our words can flow candidly, there we make epics—there where our politics flourish.

La divina mimesis too was meant to be written as a diary, in layers, every note should have been accompanied by a date, with all the additions rendered visible. Stacy applies the same principle in the central part of her book A Sentimental Education (2010-2011) where time and space are rendered visible—not the case for any of the poems, where time works differently: in the two sections of the book Pasolini Poems (2005) and Pasolini Poems :: Divina Mimesis (2020) they carry the same titles but are updated after a time span of fifteen years, and meanwhile their charm gained density and details—she’s ready to tell more. Or most likely it is us who are ready to take more in, to be more with this double-headed character who’s both Stacy and Pier Paolo, on their way to a Caracalla bath, they too are. Neither he nor she are walking alone at night any longer. And us, as an endangered community, we all feel safer.

“through brutal force

common sense becomes

underground knowledge

credentialed cynics teach

the outcome is death”

This is what writing does, it creates a correspondence that stays—as Stacy stays with Pier Paolo, I stay with Stacy—to give each other courage. Even if we end up in a place we don’t yet know, time could collapse into gratitude for some event yet to happen, a password, a shared feeling, or an image worth sharing. Then together we can stay in that moment:

“try to remember our cheeks as they were

after being kissed for the first time”