Soul and Mystery

Exercises in Coherence: words by Goffredo Parise and photos by Marcello Salustri

This post-surrealistic experiment, juxtaposing visual artworks and literary sources that apparently have nothing in common, first appeared on the issue 34 of NERO (spring 2014), when it still was a printed matter. In this “exercise in coherence” words are by Goffredo Parise, translated by Tijana Mamula, and photos by Marcello Salustri.

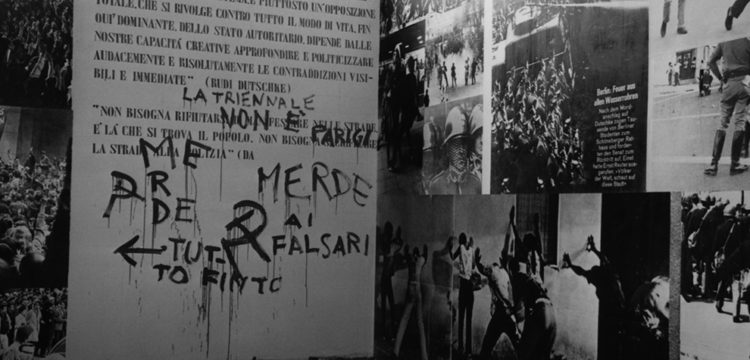

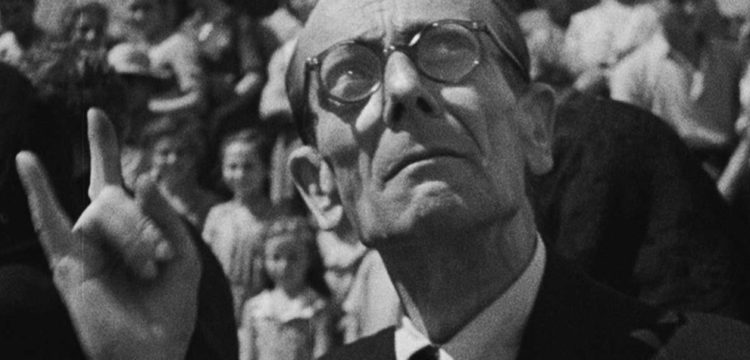

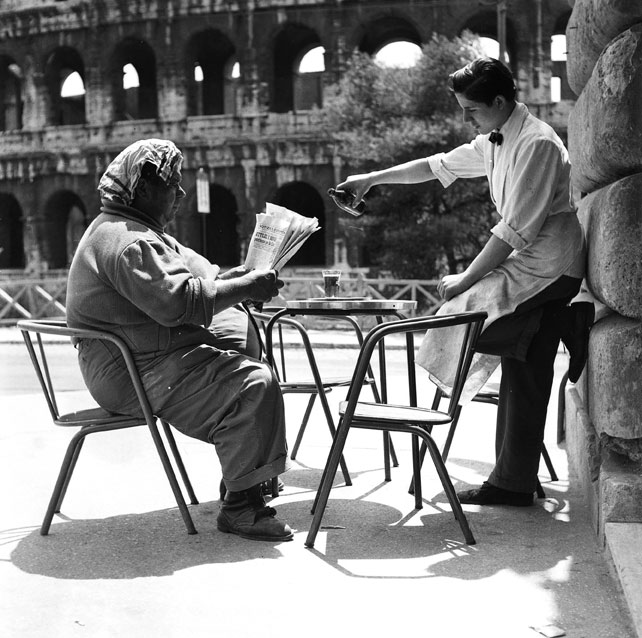

Goffredo Parise (1929-1986) was an Italian novelist, journalist, screenwriter, essayist and poet. His fiction includes the novels Il prete bello (Garzanti, 1954) and Il padrone (The Boss, Feltrinelli, 1965), and the short story collection Sillabari (Abecedary, Einaudi, 1972). His work as a journalist during the 1960s, which covered reportages from China, the United States, Biafra and Vietnam, among other countries, is collected in the volume Guerre politiche: Vietnam, Biafra, Laos, Cile (Einaudi, 1976). As a screenwriter, he co-wrote several films for Mauro Bolognini as well as collaborating with Marco Ferreri and Federico Fellini. The photos published here come from the archive of Marcello Salustri, photojournalist for the Paese Sera newspaper, active between 1950 and 1960. The archive includes more than 150,000 negatives and belongs to the Museo del Louvre in Rome. We thank Giuseppe Casetti for his king permission to publish a selection of them. We would like to especially thank Giosetta Fioroni for giving us the opportunity to republish the stories by Goffredo Parise, taken from Sillabari, and for her valuable advice during the conception of this installment of Exercises in Coherence.

SOUL

One Sunday in June, a dog named Bobi, who had and didn’t have a master, started off on a meandering journey, full of pauses, through the streets of an Italian city: it was the early hours of the afternoon, and there were few people around; perhaps they were sleeping, or at the movies or out on excursions to the hills. The bells of a Romanesque church sounded cheerfully, but less cheerfully than in the morning, and the sound threaded its way beneath the long shadow-filled porticos of an ancient deserted street that the dog was running down in little leaps. Until then he had waited, in a courtyard, inside a doghouse made of cartons of Barilla pasta, for the return of the person whom he thought was his master (the man who had made the doghouse, without however compromising himself any further on Bobi’s behalf); but the man, who almost never showed up, didn’t show up on that day either and Bobi, however reluctantly, felt himself morally free to go off and wander. He moved along prodded by a sole necessity (hunger) but by many feelings: foremost among them an enormous excitement about putting together the greatest possible number of smells, in the most diverse combinations; then by boredom, which for dogs is different, but not so different, than for people; then by the need for company; then by his self-love, which was wounded by the behavior of the master he loved without ever having had the certainty of being loved in return; finally, by the cheerfulness that he derived from his ample three-quarters of blue blood. Bobi was a mongrel but he had “in his veins” a strong dose of smooth fox terrier and only a tiny dose of various impurities, with a prevalence of short-legged dogs. This cocktail had yielded good results in him and the superiority complex of the purebred dog had almost prevailed over the inferiority complex of the mongrel, so that Bobi walked on short legs but with his head held high, often trotting nonchalantly and only rarely galloping like those who fear the infinite consequences of their uncertain birth.

Marcello Salustri, Man who lives with 19 dogs, 1951; courtesy Il Museo del Louvre

From the smooth fox terrier Bobi had inherited one of the most important traits, the tremor of excitement and the capacity for immediate, vertical levitation, from low down to high up, solely by means of a nervous thrust. Thanks to this trait, a man of unstable character but given to sudden likes and dislikes had found him (one day) very likeable, had built him a cardboard doghouse, sometimes took him for walks (but without the aid of the leash that Bobi would have desired) and, in a very vague way, protected him. All the same, Bobi, for all the reasons that have been given but maybe, more simply, by character, was not a happy dog; he was however very strong, very intelligent (that is, he understood life) and by the combination of these two things, he was “fundamentally” good. He wasn’t a snob like all purebred dogs but he also wasn’t tearful or angry or anxiously happy like all mongrels; he was an “independent.” Hunger had never been a problem for him, he had always found spontaneous benefactors; in the absence of benefactors there were the dustbins where Bobi, with his long fox-hunter’s muzzle (it appears that terriers began their worldly careers in this way, many thousands of years ago), was able to swiftly dig up the choice items, pawing everything up into the air. That day he saw two cats, one white and ginger, the other just ginger, launch themselves under a window. He immediately understood everything, but he didn’t lose his composure: indeed, from an unserious gallop he shifted into a serious and threatening trot; a wet bundle full of spaghetti fell from a window and splattered onto the ground, and in that moment the two half-bald cats saw a dog that, crying as though his throat were being slit (terrier trait), flew belly-first onto the wrapping. The two cats disappeared, harboring ill-will, and Bobi ate everything without giving heed to the protests of the old woman at the sill who threw two buckets of water on him. The bundle finished he resumed his trot, turned a corner, then another, and there he found the first nuisance: a genuine smooth fox terrier that he knew by sight was standing some forty feet away from him, held on a leash by an extremely affectionate owner, a madman with thick glasses who, as on other occasions, pointed at Bobi and shouted: “Biri, look, your enemy!” The inferno of barks ensued, Biri’s owner laughed like crazy, but it didn’t last long because Bobi only barked for form’s sake and then fled, and two or three corners later he had gone back to being calm. He knew a place, an open-air lumberyard and a deconsecrated church, where dogs gathered, but there was nobody there; he sniffed around for a long time and didn’t find any fresh traces. At that point he made his way toward the public park, a dangerous place for dogs like himself, but where you were sure to meet someone: there were usually some familiar faces, a sort of “moorish” pirate dog, getting on in years, and a chubby tottering half-blind bitch, an old, unrecognizable mixture of wretches that the Municipality left in peace (both of them avid for smells but in an indiscriminate and slightly disgusting way, like all the elderly); there was a very easy, slightly crazy little bitch, that used to disappear for months at a time; there were two half-schnauzers, “very intelligent and likeable,” that lived god knows how, perhaps protected by someone. But that Sunday not a single dog, just a military band whose playing excited Bobi so much that he stayed until the end, sniffing here and there among the few spectators, who didn’t object.

Marcello Salustri, Censored film poster, 1959; courtesy Il Museo del Louvre

From the public park he moved to the central streets of the city where there were many flags on display, other brass bands played and men in uniform walked in the middle of the road. In an entranceway that opened onto a courtyard Bobi found, very unexpectedly, four dogs that were themselves surprised by the encounter. A moment later they formed a friendship, actually, much more than a friendship; from the stray dogs that they had been until that moment, and complete strangers to each other, the five became — for who knows what chance in the destinies of all living beings — no longer a miserable canine thing (three out of five were extremely ugly, one with three legs, the others tattered from brawls and covered in bites that got lost in the meanders of their pedigrees), but rather a social union (a very small one), a historical force (tiny, of course), almost a sketch of a political organization (hasn’t the elite always consisted of a few?), perhaps with a platform. Or at least that was how it seemed: there were the flags, the bands, men in uniform marching and maybe singing hymns, but above all the five animals, venturing into the middle of the street, compact and trotting, their ears mouse-nibbled by the wind, had assumed with much faith and hopefulness a semblance that is not proper to dogs but to much superior beings. They were two very full hours, hours of “enormous interest,” and without seeking them out the dogs participated in the great and small reunions that took place throughout the day. Twice they were disturbed by purebred dogs, once by a black wolfhound that tugged his mistress towards them but not to fight, only to sniff and be sniffed; another time by two ferocious male twins, two dobermans, two SS’s, who leaped down from a jeep to attack them but fortunately were wearing muzzles. It was a vision that alarmed them profoundly and that definitively disbanded the unitary formation of the five, who all fled as far away as possible. Without knowing exactly how, they found themselves far from the centre of the city, almost at the highway exit, without any of their recent hopes, back to being dogs and nothing more.

The one with three legs tried to revive the Sunday (the sun was setting though) with two tin-cans, then with the pursuit of a tow-truck, but nobody followed him except for Bobi, who stopped after ten yards, drunk on exhaust fumes. Tottering, he cut to the right of the tow-truck and in that moment was hit by a motorcycle that braked, skidded, and continued on its way. The hit hurt him very much but Bobi made his way slowly back to the doghouse and there, without waiting any longer for the master who never came, he died. By pure coincidence, the master — well, the person Bobi had been convinced was his master — came round the following day, and remembering Bobi and certain of his own distractions with momentary pain, asked himself (or told himself?) something very beautiful and worthy of him: “Dogs have souls.”

MYSTERY

One blazing summer day, in Rome, in the quivering of the hot air that melted the asphalt of the streets and stuck the soles of shoes to the ground, a dazed man ran into a half-naked friend in a car, gesturing at him. The car stopped beside him in the middle of the road as if it was about to run him over and the friend, whose name was Piero, suggested that they go to the beach, at Ostia. He didn’t have anything to do and the great heat, which came as though from the mouth of an oven, was producing in him that sort of Mediterranean sufferance, like a boiling of the brain, that doesn’t allow for even the smallest decision. Perhaps Piero intuited this fatal immobility among the scorching Umbertine buildings, for he opened one of the car doors and pulled him inside. The first gust of air, even though it was hot, seemed to wake the man from the southern state in which he had been in the street, so much so that he started talking. “Where are we going?” he asked. “I’m taking you to a wonderful place called the hole,” said Piero. “Why the hole?” “Because it’s a bit of beach that’s closed off by a metal fence: there’s a hole in the metal fence and that’s where you go in. I have sandwiches,” Piero added, laughing, “and you’ll see the nudists.” The man, whose name was Dino, didn’t know Rome and its beaches very well and had never seen the nudists. He was naive and said:“And do we have to be naked?” “If you want, but if not you don’t have to, I’ll give you my swimming trunks if you’re shy.” They didn’t say much during the journey; the car crossed the EUR, then turned onto a small country road that Piero said ran alongside Castelporziano, the president of the Republic’s estate. Dino envisioned an immense park with wild boar and deer, like he’d heard it described, and together with the images of this vision he immediately felt the air changing, from hot to cool, blowing out of the large park, softly like from an air conditioner. All the same, he was in a state of mind, which often gripped him in the Roman countryside, of stabs and blood among the swarms of flies. They reached a road that ran parallel to the wood; Piero was wearing a large gold bracelet, full of flashes, that Dino saw shaking and heard clinking as Piero maneuvered the car onto the sandy edge of the road, then they got out with their small bags.

Marcello Salustri, Heat in Rome, 1954; courtesy Il Museo del Louvre

They found the hole in the metal fence at once and pushed their way into an area of sand dunes where a very narrow path opened up, winding through vast and thick Mediterranean vegetation. Laughing in a mephistophelian way, with screeches and short, guttural, strangled shouts, Piero led him into that vegetation, which seemed low and impracticable but wasn’t: arboreal cavities opened up in the depressions of the land, forming large and small caverns and corridors, their roofs woven with lianas and vegetation, their floors of fine-grained sand strewn with crumpled paper tissues. There was a strong odor, humid and human, like in Turkish baths. They could also hear sighs and whispers, the rustling of leaves, and Dino thought it must be boars or other wild animals coming and going through those meanders, from the president’s park directly to the sea. But then he saw two slim black bodies with tiny colored underwear run off through the growth, with that soft but broad-based thudding that the soles of feet make in the sand. He knew there were a few birds because he could hear them chirping, and he thought he saw a pheasant cross a stretch of sand lit by shaft of sunlight and throw itself into the bushes with swift, runner’s leaps, its chest out, its tiny head erect. On the threshold of that labyrinth, Piero, with his mephistophelian laughs and short cries so similar to the calls of an exotic bird, and now in the humid and almost smoky half-light, with his fox-white teeth sticking out of his crinkled lips like they would out of the jaws of that animal, put Dino in a state of unease; which was translated into a fear that the ground was covered with shards of glass hidden by the sand and that the place was populated by dangerous and deformed beings, maybe the mentally ill, who had been brought there to go for a swim and to sunbathe on that beach abandoned by everyone. They walked along another path that wound through low and thick bushes and found themselves facing a dune that was very high, like a wave. They climbed it, and from there Dino saw a wide beach and the sea. It seemed to Dino that his suspicions were being confirmed, for the first bathers that he saw nestled on the beach, covered in Arab tunics or rags tied round their waists or minute trunks with golden chains, seemed to him, with their oblique but flashing eyes in their black skins, to be mentally ill or convicts or aging cripples.

Marcello Salustri, Aspiring actress, 1955; courtesy Il Museo del Louvre

He saw mostly men: some with long white or black beards, some thin and all skin and bones, others obese and wrapped up in some kind of pink and flowery plastic underwear, tied with a rubber band around the chest and knees, steeped in pools of sweat. He saw others, young and dark with long, blond, badly-bleached hair that came down over their shoulders, who might have passed for women; but a bluish shadow of beard around their square, southern farmhand faces showed that they weren’t. Then he saw whole families under two beach umbrellas, all fat, in the very moment when they were stirring some tomato pasta inside an enormous bowl made of green plastic. These also seemed to him like families of convicts or people with illnesses of the mind or the bones, who had been granted permission to sunbathe. Finally they arrived at a little straw hut, where they changed (Piero went naked and gave his trunks to Dino) and had drinks served by a man with burnt, purplish hair, and very short and powerful legs, covered in a labyrinth of knotted veins that seemed on the verge of bursting. They walked along the beach and Dino immediately flung himself into the sea to throw cool water on those images, and came back straight away because the tall waves were preventing him from swimming with enjoyment. It was at that very moment that the place suddenly seemed to change, as if through an effect that in cinema is called a dissolve: in a sudden and out-of-focus quiver, Dino saw coming towards him, in what seemed like an absolute silence save for the sound of the sea, several groups of naked people, and he realized that other groups were lying on that stretch of sand made wet by the sea. The nudes he could see were not all beautiful and harmonious: some of them (the men) showed what looked like a little finger pointing sideways between their legs, others a huge overflowing vein, bluish and shiny, others still a mere button of flesh peeping out through their pubic hair. The women showed nothing except their breasts and pubic hair but what struck Dino about them was the many different types of flesh, which must in every case have formed about ninety percent of their weight, as if they had no bones. A girl with long copper hair, who was coming out of the sea at that moment, had flesh that seemed to Dino very beautiful, light and elastic, milk-colored, and as though inflated with a bicycle pump, so much did the breasts and buttocks appear suspended in the air by the propane gas of fairground balloons. All this nudity seemed to Dino playful and light, similar to toys and to food, balls, buttons, little childlike hands and arms, tripe and bells of veal on display at the butcher shop. Unlike the bathers he had seen earlier, who had seemed to him so threatening, with a past of crime and blood, of drugs and hereditary deformities, these total nudities seemed to him more well-mannered and light, like non-threatening bodies from which the animal and threatening aggressiveness of covered genitals had been stripped away like a bathing suit. “How strange,” he thought, “a few minutes ago everything seemed mysterious and terrible, now everything seems bright and harmless, all it took was a few yards of beach.” He said this to Piero, who laughed in his lynx-like way. But even that laugh no longer had any effect on him, and the mystery that had endured from the flames of the morning sun was swept away by the breeze.