Soft Cannibalism

A conversation between Aleksandra Sidor and Bogna Konior

Soft Cannibalism is a conversation between artist Aleksandra Sidor and writer Bogna Konior, held on the occasion of Sidor’s solo painting exhibition. Using the show as an entry point, they reflect on the conceptual threads underpinning the work, as well as shared themes in their own practices, such as technology, eroticism, and violence.

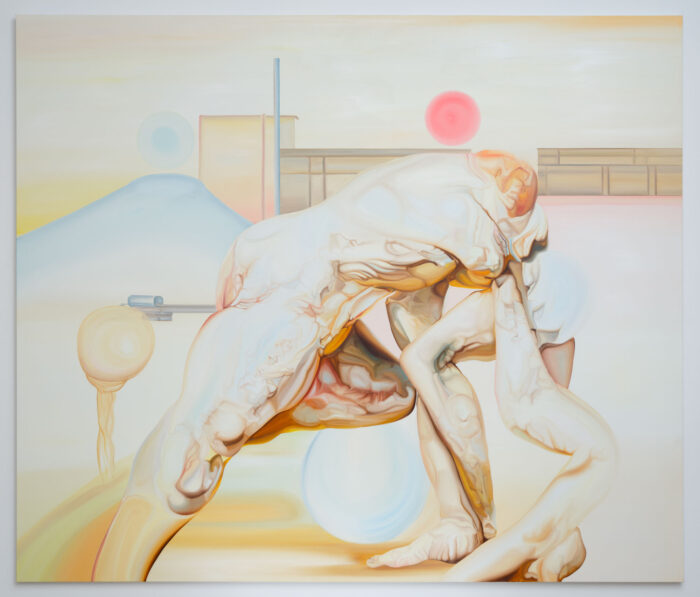

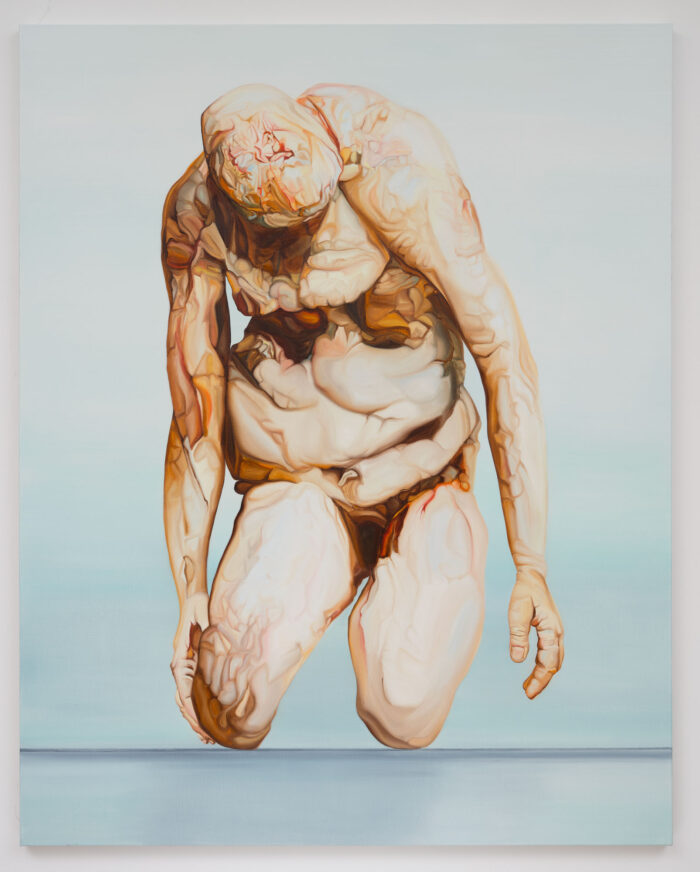

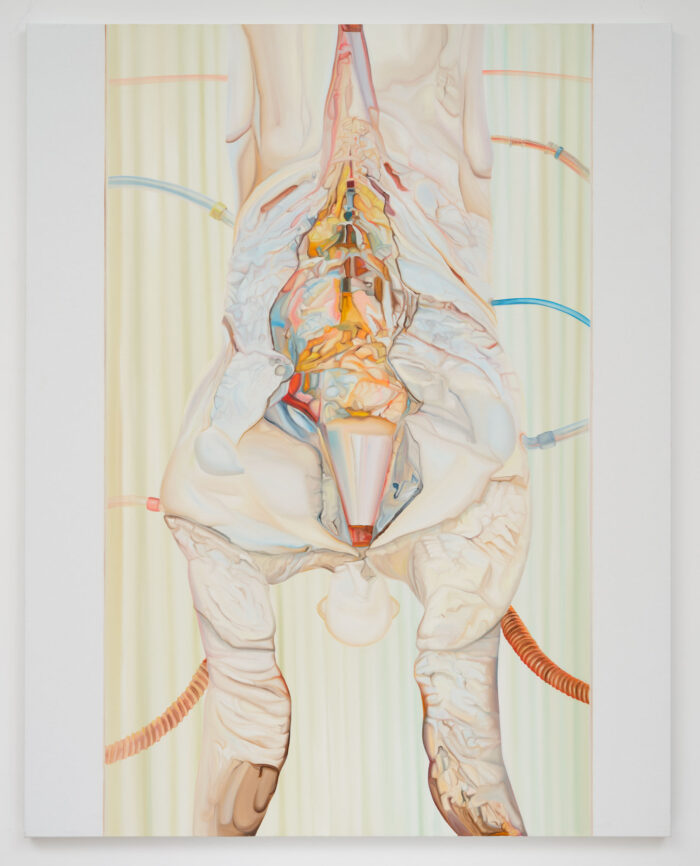

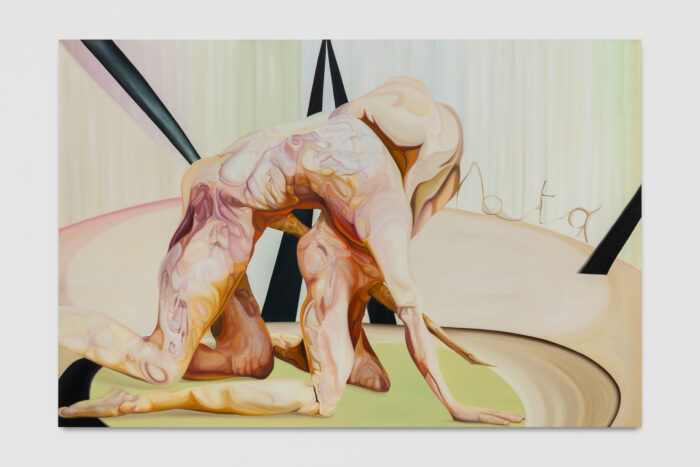

Bogna Konior: Your current paintings depict the human body in transformation. While the pastel colors are gentle and alluring, the scenes could be perceived as traumatic—bodies metamorphosing, changing shape, falling apart. Though your interest in death, taboo, and cannibalism might not be immediately apparent, themes of submission, consumption, and transcendence of social norms permeate the exhibition.

Aleksandra Sidor: Cannibalism is the biggest taboo in our world. The very possibility of it appears as an unmentionable horror, almost universally condemned. I find traces of cannibalism in the popular horror tropes that we are obsessed with, such as vampires, aliens, zombies, and monsters. The terrifying notion of humans potentially moving down the food chain is very much alive and well. As a society, we can fixate on people like the serial killer and cannibal Jeffrey Dahmer, because he represents it. But by making just one person into a symbol of cannibalism as the ultimate evil, we repress the knowledge that historically cannibalism has not been just an individual deed, and has not been usually related to murder or crime. It has been practised socially, collectively and in multiple ways. It has underlined histories of religion. It is part of who we are as a species, yet the idea of eating other humans to prolong your own life, even if it involves no violence towards anyone, is the ultimate taboo.

BK: The philosopher Julia Kristeva’s concept of “the abject” describes our feeling of disgust toward anything that was once part of “the self” or our body. Urine, blood, feces, cut fingernails, or hair in the shower drain—these were all part of us moments ago and aroused no disgust. Yet the instant they detach from us, they become unbearably repulsive. This shock and disgust serve as defense mechanisms, shielding us from confronting how we are all composed of death and waste, inevitably becoming corpses. Where do I end and where does the “dead” part of me begin? Kristeva argues that the human corpse is the ultimate abject—something that was just moments ago a complete self, like you and I, but is now cast out from meaning. Perhaps cannibalism represents the ultimate taboo because it brings us too close to our awareness of human death and waste, literally reincorporating it back into the body, absorbing it back into “the self.” How we delineate the boundaries between life and death, organic and inorganic, life and decomposition, ultimately defines both “the self” and our confrontation with other forces entering ourselves.

AS: I have been studying Freud’s work and consider parts of it quite relevant. However, I wonder if we could update it by considering more recent debates in anthropology and biology. In Consuming Grief: Compassionate Cannibalism in an Amazonian Society, anthropologist Beth Conklin writes about mortuary cannibalism, which is eating the bodies of one’s own community members. She conveys some of the Amazonian ideas about the body as generous and porous, leaking substances such as blood, milk, semen, or vaginal secretions. When a couple is pronounced husband and wife, it is said, “they are now one flesh.” The book features a scene reminiscent of the bonding fantasies in the popular teenage romance movie Twilight, where a future fiancé, Jackob, is “imprinted on” a baby, creating an intimate, involuntary bond. Similarly, in the Wari’ tribe, the future fiancé is encouraged to hold the newborn baby. The baby is still covered in postpartum blood and this ritual symbolises the bonding and exchangeability of bodies. The idea of a body as composed of substances acquired from others contrasts with that of the supposedly autonomous and socially unconstrained soul. Nevertheless, the tribe refrains from consuming their direct kin, as that would be considered “self-cannibalism.” However, distant relatives can be eaten.

BK: In his book Soul Hunters: Hunting, Animism, and Personhood among the Siberian Yukaghirs, anthropologist Rane Willerslev explores practices of eating, hunting, and intimacy. Yukaghir hunters view the relationship between predator and prey as a dance of seduction, where success comes when the animal willingly surrenders to the hunter, like a promised bride. This process relies on mimesis and mimicry—but not complete metamorphosis. The hunter must mimic the prey’s movements and partially embody its nature to understand it, yet cannot fully transform into it. If a hunter identified too closely with his prey or truly became the animal, the hunt would fail. Similarly, if the animal were seen as fully “human,” consuming it would constitute cannibalism—a forbidden act. These examples reveal how various cultures maintain complex prohibitions and rituals around intimacy, bodies, and eating. The relationship between modern and pre-modern practices isn’t simply a matter of decreasing cannibalism—rather, eating continues to occupy significant symbolic dimensions. Take vorarephilia, a cannibalism-adjacent erotic desire where one fantasizes about consuming or being consumed by another being, human or nonhuman. Soft vore differs from cannibalism in that it remains a supernatural fantasy: the consumed person is swallowed whole and later expelled intact.

AS: This morning, I read about a complex and unusual case of vorarephilia. Some fetishists imagine themselves as predator animals, such as cats, wolves or snakes. Those who wish to be consumed often portray themselves as small, weak animals like mice or rabbits. The concept of identification between the Yukaghir hunters and their prey distinctly reminds me of these bodily descriptions found in the writings of vore enthusiasts. Moreover, vorarephiles have an intriguing interest in pregnancy. The pregnant or “full” belly is fetishised as a symbolic link between two life-sustaining activities: giving birth and feeding, or being fed. It wouldn’t be surprising if we discovered more interconnected dynamics, such as those involving exchanges of points of view between the oppressor and the victim (as seen in the research by Eduardo Viveiros de Castro on the Tupinambá case).

BK: In popular culture, anthropology evokes images of hunter-gatherer tribes in jungles. Though born during Western European colonialism, this academic discipline offers insights into our own cultural practices—particularly Polish Catholicism with its seemingly cannibalistic element of consuming Christ’s body. The Church insists this is no metaphor: the Eucharist is literally God’s body. While Protestantism rejects such elements, Catholicism embraces deeply ritualistic, sensory, and embodied practices. Computation of Lack is my favorite painting of yours as it weaves together my cherished themes: eroticism, Catholicism, technology, and Polish cultural heritage. The title also references psychoanalysis, doesn’t it?

AS: While I am aware of creating my work with a deliberate mix of thoughts in mind, enriched by visual clues that redirect its meaning, I always evaluate it against its title and broader potential interpretations. In doing so, I strive to set aside my previous theoretical points of reference—if applicable—and imagine how it might appear through the lens of the so-called imaginary “common knowledge.” This is an impossible task but a deeply enjoyable one—a sort of critique with myself. If I manage to arrive at multiple conclusions based on a visual reading of a single piece, I congratulate myself with a “Good job, Ola, well done.” Five minutes later, I despair, convinced I am the worst artist on earth, and I end up having nightmares for a week. This cycle repeats often. During the exhibition Test Drive, Computation of Lack existed in dialogue with a short story that vaguely described a futuristic world and its ideological structure. My hope was that this connection would encourage viewers to explore alternative readings and reimagine the potentialities of our current perspectives. Simultaneously, I was developing a theory called the “Thyestes Complex,” which drew on Freud’s writings and 21st-century anthropological studies to explore themes of cannibalism. My aim was to test this theory against my own work and examine how interpretations might shift when viewed through an abstract creative framework. In essence, I sought to put into practice the concept of “going beyond representation” through meaning. At the heart of this process is my deep belief that art transcends my own understanding—that it is far greater than I am. Initially, I was inspired by Georges Bataille’s and Jean-François Lyotard’s writings about the libidinal economy and the religious character of desire. Religion and desire are interrelated, and human desire has a religious dimension, along with corresponding ideas of lack and transgression. This painting is also inspired by your essay about Faustyna Kowalska, the Polish stigmatic and mystic, Determination from the Outside: Stigmata, Teledildonics and Remote Cybersex. I think she was quite transgressive. Kowalska’s immediate community was not completely on board with her visions. The other nuns thought she made it all up and they didn’t like her.

BK: A lot of them didn’t. If you read her diary, they often seem to suggest to her that she is just a spoiled brat, a narcissist. “Oh, you think you’re talking to Jesus, whatever.” She did have a quite annoying, holier-than-thou personality, which didn’t help.

AS: Her eroticism is the perfect example of violent Bataillean transgression: bodily pain and suffering of stigmata combined with her love for Jesus, whom she cannot “reach.” The lack of divine touch and the transgressiveness of pain she uses to fill it. Her pain and her ecstasy were both against the social taboo. And just as you write, it is interesting to ask if machines today could perform that sacred function that divinity used to, or if they could fulfil us emotionally and erotically, and hence spiritually.

gratin. Photo Argenis Apolinario.

BK: With the increased mythologization of AI as a social presence, we’re likely to see a growing desire to be cannibalized by machines. The nuns anticipated this phenomenon—though they yearned to be consumed by angels rather than machines. There’s an overlapping theme between your interest in cannibalism and mine in erotics: both explore how bodies register and incorporate external forces. In both cases, the border between self and other becomes blurred. What does it mean to be dispersed, to fall into pieces, to be eaten? The body melts and submits. This stands contrary to mainstream technological narratives like transhumanism, where we biohack ourselves to become more defined, stronger, faster. While this romantic Promethean trope of human mastery over nature and body through technology persists in social imagination, cannibalism and eroticism offer alternative trajectories—ones where the body remains pliable and receptive.

AS: The bodies in my paintings are pliable and interactive. They are open, constantly engaged in an exchange with their environment, never closed off. Perhaps this reflects the inherently collective nature of human cognition and the way new cultural formations and technologies are reshaping our minds, as Brian Rotman suggests. Or maybe I’m simply painting deep-sea creatures in human form, or exploring the transgression of boundaries that occurs with both love and death, crossing taboos. Maybe it’s all of these things, or just some of them—who knows? I enjoy what I do, and often I find it profoundly beautiful. When taboos are crossed, there is a complex interplay of pleasure and pain, enjoyment and guilt. Freud wondered if taboos are something innate or contingent on social dynamics. If social dynamics change, would we have different taboos? I was thinking about how interesting it would be if sexual reproduction wasn’t necessarily needed anymore. How would our bodies change, what would they register in this new paradigm of sexuality, without feeding and nourishing babies as necessary elements? Would some taboos simply disappear?

BK: That’s also my fantasy. Sexuality can be experienced through machines, but what about pregnancy and child-rearing? That’s what I want to see.

AS: Me too. It’s so exciting to think about whether bodies could return to the state when there was no differentiation between sexes, no reproductive functions. Back to the inorganic and the place with no sex. Perhaps, like these primal forms, our sensory experiences would get all confused. We could experience sexual gratification from food intake or from expelling waste, for example.

BK: Developing erotic relationships with machines could expand our understanding of sexual possibilities—both in terms of erotics and reproduction. The Virgin Mary offers an illuminating parallel here as the original icon of asexual reproduction. As a cyborg figure, she reproduces without human sexual contact, impregnated instead by an angel—an inhuman agent. In this sense, Jesus is essentially Mary’s clone, one body replicated from another. The Virgin Mary represents an allegedly unattainable ideal for women through her ability to procreate without sexual intercourse. But what if this becomes technically achievable? While pregnancy is currently viewed as a fundamental feature of certain bodies, and some feminist philosophers argue that women’s capacity for relational thinking stems from their ability to split themselves to host another life, what happens when this is no longer biological destiny? What becomes of sexual difference if pregnancy transforms into a generic technology available to all? These fundamental questions about cannibalism, sex, and erotics begin to intersect. How do we define ourselves in relation to nourishment, sustenance, and the creation of life?

AS: This is one of the questions that inform my current set of paintings. The other would be: what does it mean for one body to consume another similar body? How does our social body and psyche change over time? How to construct a world in which the body is actually embracing these changes?

BK: You’re interested in thinking about the body in relation to dynamics that aren’t entirely conscious or simply “social”—a perspective often emphasized in today’s international art communities with their belief in directing history toward “progress.” Instead, you reflect on cycles of desire and death. The body isn’t structured solely by our choices—it’s like a canvas that registers and absorbs countless external forces. I’ve been wondering whether Eastern Europeans, compared to Western Europeans, are more inclined to think this way in our current moment. This refusal to reduce everything to social dynamics and progress—to “what’s good for revolution, what’s good for society”—might stem from our post-communist legacy, following the disastrous collapse of progressive narratives that reduced culture to a mere political tool. Many Polish intellectuals I admire, both for their politics and their intellectual or aesthetic achievements, defied this logic. They refused to reduce humanity to social dynamics or subordinate culture and thought to political imperatives. These days, I find myself returning more frequently to the texts I read in high school.

AS: Perhaps I am less likely to think about art and culture in those terms, because I am aware of how it all once played out. The failure of progressive and communist narratives about art is our legacy, it is the lived experience that is so fetishised these days. In your recent book chapter The Gnostic Machine, you wrote about Stanisław Lem’s experience with communism, from enchantment to disillusionment. Many of us will undergo a similar journey with some ideology we are invested in very deeply, but then come to reject, even if some central tenets still speak to us. For a while I was invested very deeply in progressive feminism as taught at critical theory departments at western universities, and I wanted to instrumentalize myself and my practice in its service. Then, the escalation of war in Ukraine happened in early 2022, just twenty minutes away from my hometown. I could not see anymore the congruency between the ideological tools I was given at these schools and what was playing out in my life.

BK: The philosophies we read both shape and reflect where we are in life. Readers sometimes tell me my texts are nihilistic or pessimistic because they don’t offer prescriptions for making the world better. In Dark Forest Theory of the Internet, I write about cycles of violence and entropy that belong to the fabric of the cosmos and lie beyond human control—much like your interest in the unstoppable cycles of compulsion, violence, and desire. There is limited capacity for change. Others immediately ask, “Well, why talk about it if we can’t do anything about it?” I find this question bewildering—this notion that culture must serve a purely utilitarian function, like a tool for fixing a broken sink. I see profound value in the minimal freedom of confronting truth and the world in its brutality. This confrontation is the first step toward any ethics, compassion, or forgiveness for the world and each other. One must look the world in the face, understand what one is dealing with, and learn not to recoil from horror with promises of utopia. Perhaps this, too, is the legacy of post-Soviet intellectualism: my distaste for utopian promises that ignore the truth of human experience and worldly reality. It is both patronizing and spiritually offensive to be deceitful about the world.

AS: I agree with everything. But I doubt that the idea of a “limited capacity for change” will soon permeate the mainstream consciousness. It’s a somewhat daunting notion, as it implies a degree of hopelessness. Perceptions regarding our civilization’s capabilities are highly subjective, and often deeply intertwined with one’s worldview, particularly in how one perceives and copes with suffering and the essence of life. I wish that, at the very least, we could collectively agree on the idea that we inherently don’t know what life is. Unfortunately, this aspiration appears to be equally futile. I am also very fond of the idea that people’s defense mechanisms are a contributing factor here. If we were to fully comprehend the sheer number of diseases, potential everyday accidents, natural disasters, and countless man-made harms, we would be overwhelmed by fear and unable to function. To cope, we shield ourselves from these possibilities in our daily lives. While this defense helps us manage the mental overload, it can also result in many consequences, including an inability to connect certain misfortunes with the inherent realities of the world. The feedback you received is reminiscent of the initial (and current) treatment of the “death drive” in academic circles. I’m always interested in various cultural interpretations of it, yet the term predominantly remains associated only with BDSM. It seems as though, as a society, we suffer from a form of amnesia when it comes to the ontology of this term. In Freud’s writings, particularly in Civilization and Its Discontents, he proposes that individuals will always be at odds with community. The idea that art can “change the world” in any simple or understandable way that can be pre-designed is also at odds with how we experience art-making on a “personal” level. The most foreign experiences-pain, depression, the desire to make art-are supposed to be instrumentalized for some clear social goal. But, at least from a psychoanalytic perspective, art can also be where we sublimate our aggressive, narcissistic or sexual drives in ways that are contained, and therefore not released into the social realm in harmful manners.

BK: When an individual becomes part of a group or community, something is violated. This violation is necessary and unavoidable—not something one can opt out of. Yet there’s something indescribable and universal about every human that needs protection, something that collective identity can never fully capture. There is always an excess. Simone Weil writes about the difference between “the impersonal” and “the collective.” The collective is the sphere of ideology and the social, where people form political goals around communal identities: “We’re women,” “we’re Polish,” “we are anarchists.” You name yourself to seek representation and allies—it’s necessary—even though ultimately, you want to shed these masks, to make them irrelevant. You name yourself hoping that at the end of your struggle, you can stop speaking about yourself entirely and simply be left in peace. Weil argues that this “collectivity” is a poor substitute for the impersonal, which she sees as the true revolutionary axiom, one resistant to corruption. This is the basic, impersonal element in all humans—perhaps it’s the vulnerability of the body, something that defies representation and language, something wordless that needs protection in ourselves and others. Perhaps it’s our capacity for pain, transformation, and erotics. These qualities escape naming and signification. In our work, we may be trying to grasp this: not to represent something but to show that not everything can be neatly captured and turned into an action-oriented goal. The question becomes: how do we sustain in each other what cannot be spoken?

AS: People will often say how art needs to be seen through the artist’s personal life or their historical and social context. I disagree with that. No one can fully understand either themselves or another person, and yet you see that much interpretation of art cannot go beyond the knee-jerk impulse of trying to “contextualise” the artist psychologically or historically. “Oh, she meant this or that because she grew up during the war.”

BK: Fredric Jameson described this as the impulse of our current era: “always historicize!” This manifests when art is emptied of all meaning except as commentary on current events. To the artist, this becomes a violation—being forced into a certain representation that is inherently incomplete. You cannot be whole in it or recognize yourself in it. Isn’t this the terror of the social—naming us and reducing us to the comprehensible? This burden falls especially heavy on those from places perceived as “not yet named enough.” Being a woman, an Eastern European—these become the dominant lenses through which the art world consumes you. Who gets to be perceived as the universal, the human, and who remains the particular element that must be understood in context? What you said about non-biographical approaches resonates with me. Virginia Woolf said that writing is essentially about “becoming no one.” Even when speaking of particular experiences, you must become no one to do it. The big reveal is that as an artist or writer, you might not set goals or have interests—you simply show up for something to happen through you.

AS: It’s complex, sometimes you have to go through your whole life to reflect properly on the things that you made. Eventually, you might end up with some grand story about it. I find this attitude similar to what people often do in therapy, when they create “classifying” narratives about themselves and their lives. They find the one narrative that fits and settle with it. I’m not saying that this approach is necessarily false; it’s just that there might still be more to it. More stories. Everything and anything might flow into a life or into a work, and is not reducible to a simple historical perspective. Interestingly, before the current war, my bio used to state that I was from the middle of nowhere. However, I have since removed it, feeling more “Eastern European” for a while. Ironically, being from the “middle of nowhere” initially referred to Bournemouth in the UK, and later to Tomaszow Lubelski, my current place of residence. I still recall that as a child, my deepest wish was to be from nowhere.

BK: Recently, some friends and I discovered an online manifesto for Polish futurism that called for mobilizing national, folkloric imagination to create a local futurism. However, I believe that speaking authentically from Poland or Eastern Europe means speaking from the experience of being “in the middle of nowhere”—a footnote to Western history. Eastern Europe must remain invisible to Western Europe because it was the actual battleground where the struggle between Nazism, communism, and capitalism played out, giving weight to all current debates in the Western public sphere. I created a short video lecture titled “Poland, which is nowhere,” referencing the play Ubu Roi, published in 1896. This play, considered by some to be the beginning of modernism, is set “in Poland, which is to say nowhere” because Poland was under occupation then and absent from official European maps. For two centuries, discourse has circulated about Poland being an unreal or non-existent place unable to establish its identity. What if we were to embrace this displacement as something to identify with? How can we speak from our specific history without being reduced to historical narratives? Perhaps we’re responding from a post-Soviet perspective, where our national cultures were reduced to folkloric performances of happy differences within the Soviet Union’s “multiethnic empire.” But what if local places have vital contributions to make to universal human experience? What if we are not a divergence from history’s axis, but part of that axis itself?

AS: The Soviet visual aesthetic does indeed influence. When I ask my neighbour, who is a doctor, for anatomical illustrations references, she provides me with Russian books. It’s not something I can separate myself from. It’s important to acknowledge the colonisation in our past. We also can’t reject what had already been done and what we’ve been exposed to aesthetically.

BK: But your paintings have a soft aesthetic quality, characterized by the pliable nature of the body and gentle pastel colors. Rather than transcending the body, the work explores an interplay of pleasure, fear, and transformation.

AS: I think it just happened to me. I don’t know why, but I’ve always been unable to create a painting without including a body. Without it, the paintings feel empty, leaving me with a deep sense of dissatisfaction. In the past, I struggled with my work for a long time. I painted in my early 20s, but during my university years, I shifted to new media and installation art. Transitioning back to painting felt natural conceptually—I began using photo manipulation and various tools to achieve the outcomes I envisioned. It took me a long time to find my footing, and my failures are still visible online. I don’t hold a conservative view toward AI—for now it’s just another tool. The panic surrounding it reminds me of when people first started “officially” painting from photographs. Whenever someone describes my work as “confident” or “collected,” I can’t help but laugh because my process is anything but. I go through absolute chaos and countless breakdowns to make it all work. Most of the struggle happens on my computer, some on the canvas, but this separation is likely what gives people the impression that my work is organized. In my creative process, I explore a range of techniques and view my studio as a construction site: interpreting photographs, employing collage and automatic drawing, reconfiguring sculptures modeled in Sculptris, and abstracting forms from 19th- and 20th-century anatomy atlases as well as AI-generated images. Each piece demands something different, and I adapt to meet its needs. Reflecting on my methods has shaped my outlook, but a life-or-death experience in my personal life also compelled me to reevaluate what I consider meaningful in both life and art—and what I truly want from them. This inquiry is ongoing. What I know for certain is that one of the most precious qualities of art—its ability to foster meaning—is conspicuously missing from the contemporary art world. This absence, among other things, makes the art world feel shallow and devoid of nuance. I used to love the IMDb boards for their chaos and the abundance of contradictory opinions they offered. That dynamic, meaning-making quality is largely missing today, which makes everything feel far less vital. I’ve reexamined the art I once valued and reflected on my pursuit of art as a constant adventure—one that, at times, felt devoid of meaning. Yet, I deeply value meaning and the transcendental quality of its multiplicity.