Sensing the Liminal

Rebecca Salvadori’s experimental filmmaking and techno raves as spaces of subjective recomposition

Addressing subjective struggles and forms of collective rituals within the context of techno raves, the films Tresor Tapes and The Sun has no Shadow by Rebecca Salvadori develop as sites of experimentation, rather than tools of representation.

There is often a sense of melancholia when one enters a closed club during the day. That space that at night is a pulsing organism now appears just as a place of empty rooms and tech equipment. Its boundaries that expand and contract according to the music and the movements of the people dancing turn out to be just walls made of bricks and concrete. Darkness, fog, and flashing lights that do not allow to clearly see what is happening are now replaced by a flattening all-too-revealing natural light. And for some reason, during the day, the space always looks smaller than at night. So, one wanders around the rooms of the club with a sense of disappointment as she realizes that a club is just a space, at the end, like many others. All those overwhelming forces that animate that place at night are actually something very ineffable, which just disappears without leaving any traces once the party is over. To grasp and represent those intangible elements which turn the club’s space into a living organism is therefore an arduous task. To do so, one is required to develop a series of aesthetic and narrative strategies, which, in the best case, would only allow a glance into its multidimensional and plurisensorial reality.

From two opposite, yet specular, points of view, the films Tresor Tapes and The Sun has no Shadow by Rebecca Salvadori take up the challenge of deploying images—specifically moving images—to represent the ineffable reality of a club, also as a stance to explore the expressive potentialities of (moving) images. The two films explore aspects of techno culture through the cinematic medium, both as an individual journey and a collective ritual. Yet this binary relation between them resonates in all the crucial aspects of the two video works, enhancing the tensions between these two sides. The Sun has no Shadow takes place in the city of London, with its pivotal location at the techno club FOLD, and is composed of a selection of footage shot by the artist over ten years; Tresor Tapes, instead, commissioned by Berlin’s techno club Tresor, is realized using footage from the three-decade Tresor’s video and sound archive. As a result, the two films develop according to two specular logics, leading to different, but complementary, results. The Sun has no Shadow unfolds as an individual process of recomposition of the artist’s personal archive in which her subjective struggle and affective experience operate as the film’s common thread, combining its various parts according to her specific intentions. Contrarily, in Tresor Tapes the artist functions more as an impersonal vector ordering diverse cinematic elements taken from the various layers of Tresor’s collective archive, to which multiple anonymous filmmakers have contributed with their visual documents. As a result, while The Sun has no Shadow unfolds as a consistent narrative intentionally developed by the artist, based on her individual memories and experiences, Tresor Tapes emerges as a multifaceted narrative from the collective memories and experiences of a whole community.

Screened side by side at Kraftwerk in Berlin for the 31st Tresor’s anniversary exhibition Die Grosse Freiheit, The Sun has no Shadow and Tresor Tapes mirrored their narratives and approaches into each other. Yet because of this double perspective, the two films allow for the highlighting of elements related to the tension between collective and individual, beyond the specific scenarios represented in the films. The techno club is—rightly so—the environment for the exploration of this fundamental aspect of human coexistence, as it is a site where the tension between the two dimensions is powerfully activated and intensified, taking the form of a ritual. “You go down there and there’s something different—as it is stated in Tresor Tape—, you were not the person you were upstairs”. The relation between the individual and collective dimension has indeed always been a troubled one. In every system of human coexistence, they imply and exclude each other, generating an irresolvable circular process that informs them with a destabilizing logic. The very structure of human communities is thus fundamentally constituted by what at the same time threatens their existence. This potentially destructive force is, however, usually deactivated by forms of collective ritual that allow it to be processed and transformed into creative energy able to activate processes of subjective decomposition and recomposition.

Despite their fundamental differences, in both Rebecca Salvadori’s films, techno raves emerge as forms of rituals that are able to allow such a process to take place. “It’s a ritual,” as it is bluntly stated in The Sun has no Shadow. Specifically, the kind of rituals to which techno raves are often associated are those of collective trance. Generally speaking, trance (from the Latin transire, to go across) indicates a state of altered consciousness in which the regular cognitive and perceptive functioning of an individual or a group of people is momentarily suspended and replaced by behaviors that are not conformed with the norms of the community to which they belong. The phenomenon of trance, seemingly present in most human civilizations, initially appears as spontaneous, then, with the growing complexity of the social fabric of human communities, it becomes controlled, regulated, and used for collective purposes, such as religious, divinatory, or healing functions. Thus, from being a casual event, through socio-epistemological apparatuses, trance is turned into a ritual practice managed by people, i.e., shamans, sorceresses, and ministers, who have the expertise to deactivate the trance’s destructive potential and even benefit from it for the whole community.

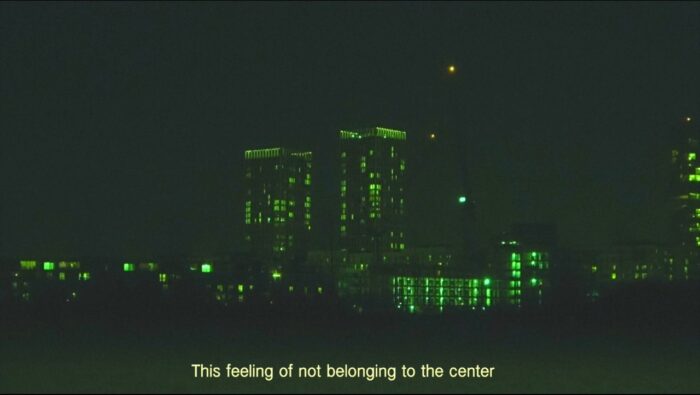

In his Essai sur la transe (Essay on trance), the French anthropologist Georges Lapassade analyses trance rituals from different geographic areas, highlighting the unique trajectory that trance has had in the European civilization. With the emergence of Olympian religion and the cult of reason in ancient Greece, trance rituals have been banned from mainstream culture and replaced by their sublimated representation, that is, theatre. Trance rituals, however, have not disappeared, but have submerged, becoming the expression of subalterns and marginalized people. According to Lapassade, techno raves are indeed one of the forms in which trance rituals have continued to exist at the margins of Western culture. This subterranean movement is what at the end of The Sun has no Shadow, quoting the Italian philosopher Elémire Zolla, is described as “inhabiting a cultural elsewhere, a coherent, scarcely systematic and hardly definable thought, constantly moving through history and latitudes, showing men [sic] that they all share a common root.” A statement that resonates with the trajectory of techno and rave culture, which, starting from Detroit’s black working-class community in the mid 80’s, crossed the Atlantic to resurface in German industrial centers and crumbling cities like Berlin. From this city then the rest of Europe was contaminated, causing in a few years the mushrooming of techno clubs and communities in many cities around Europe: from London to Krakow, from Manchester to Naples, from Bologna to Moscow and Brussels.

The individual-collective tension activated in the techno club is articulated in similar terms to Lappasade’s ones by the British musicologist Philip Tagg in his article From Refrain to Rave. Here he notes that “techno-rave puts an end to nearly four hundred years of the great European bourgeois individual in music”. In order to explain this historical rupture caused by techno-raves in European music and Western modernity at large, he refers to “the relationship between, on the one hand, the advent of the figure/ground dualism in European visual art, with its central perspective, and, on the other hand, that of the melody/accompaniment dualism in European music. These developments in European art prefigure and/or accompany the rise of the bourgeois notion of the individual.” Thus borrowing a terminology from the visual art field, Tagg describes techno-raves in terms of the dissolution of The Decline of Figure and the Rise of Ground, as the subtitle of his essay eloquently states. This process of dissolvement of the figure into the ground is valid for both techno music itself and the way in which techno is experienced. In techno music the figure, i.e., the melody, has dissolved into the rhythmic base, in the same way that the individuality of who participates in techno raves vanishes into the crowd. These effects on individual subjectivity described by Tagg seem to be coherent with what some of the people interviewed at FOLD affirm: “here I can be myself. No one will actually care,” or “when I’m here I don’t feel judged,” or “darkness and nighttime it kind of allows me to feel a bit more under the cuff.” So the desire of being oneself actually coincides with a desire of anonymity, of being disengaged from other people’s gaze and disappearing into the crowd.

To operate as a filmmaker within this context is clearly not an easy task. The attempt to represent what constitutes the life of a club by looking at its material elements is always doomed to fail. Music + space + people + substances etc.—there’s always something that inevitably escapes the equation which seems to be the crucial element to really comprehend what that thing is about. The complex liveness of a club, so pervasively present when one is immersed into it, becomes hardly accessible to the eye of whoever intends to represent it. This is a distinction clearly drawn in The Sun has no Shadow: “you can either be in the moment or be reproducing the moment, and if you’re reproducing the moment, you’re conscious but not present.” Yet that immediate presentness lost in the process of re-presentation can be partially reconfigured on a mediated level. Living organisms, such as a club at night, as evolving in time, can only be fully experienced through a direct and immediate relation taking place in the present. In this context, images and the cinematic medium show all their limits. Thus only by being skeptical towards the ability of images to represent what lives, and recognizing their inherent limitations, one can deploy images effectively as means to approach the real. Only when one is aware of the deceptive nature of images and does not get fooled by their seductiveness and delusional presumption to faithfully reproduce what is real and what is living, images manifest their actual representational (im)possibilities and, as a result, they become a site of experimentations, rather than tools of representation. Likewise, to represent a hardly definable subject, such as a techno rave, a system of representation, such as a film, cannot just copy or reflect its subject, but has to decompose and recompose it within the specific dimension of the medium deployed, according to its own logic and possibilities. Interestingly, in Rebecca Salvadori’s films, this process of reconfiguration also involves the accordance between images, sound, and language. Voices are often distorted and disconnected from the images; their sound sometimes completely disappears, leaving subtitles as the only trace of their previous existence. The original juxtaposition of those three different semiotic levels—images, texts, and sounds—cannot be taken for granted, and in films they often lose their initial coordination, finding more effective ways of intersecting each other to create new patterns of meaning.

Rebecca Salvadori’s films The Sun has no Shadow and Tresor Tapes appear therefore as cinematic works informed by a dynamic balance of unresolvable tensions such as individual knowledge-collective rituals, systems of representation-immediate experience, moving image-techno raves. Embedding these dichotomies within her works, Rebecca Salvadori opens up new perspectives on these issues, turning her films into wider spaces of reflections that overcome the specific scenarios represented.