Second-Order Reality

A conversation with Carola Bonfili

A “second-order reality” typically refers to a type of perception derived from the interpretation of observable data. Unlike first-order reality, which precedes it, this perception is influenced, and to some extent shaped, by signification. Beyond its physical properties, the world therefore appears relative, codified through systems that modify its meaning and, consequently, our experience.

Recipient of the eleventh edition of the Italian Council, Carola Bonfili’s project takes its cue from this notion to explore certain perceptual states capable of projecting singularity beyond one’s identity and bodily boundaries. Recurring in magical thinking, virtual experience and childhood, these states produce a sort of detachment that facilitates the identification with otherness and the exploration of liminal conditions.

Promoted by Fondazione SmART and curated by Ilaria Gianni and Daniela Cotimbo, Second Order Reality consists of a VR video, a trailer and a series of installations which replicate settings and characters from the story, as well as physical renders used for their digital transposition.

Like a Bildunsgroman, Second Order Reality follows a young protagonist, the monkey M’ling, along a journey of self-awareness and acceptance of her own nature. A change takes place: when she sees her reflection in the river, she discovers that part of her face has suddenly turned to stone. She doesn’t know why this happened but feels she must seek answers elsewhere, outside her village, in places she had never explored before. Her journey will be marked and guided by an inner melody, the key to nearly restoring her appearance.

Giulia Gaibisso interviewed the artist to explore the genesis, the evolution and the critical issues raised by the project.

Giulia Gaibisso: As mentioned, Second Order Reality is a project that explores those perceptual conditions capable of producing an “abstraction from the self”, a temporary loss that seems necessary to achieve an otherwise inaccessible consciousness.

It’s no surprise that your literary references include Gustave Flaubert’s The Temptation of St. Anthony, which, in an imaginative and rather baroque manner, describes the diabolic visions rejected by the Egyptian saint. His hallucinations are primarily visual, whereas in M’ling’s story sound plays a crucial role, both formally and narratively.

Where does this choice come from? What value did you actually assign to sound throughout the project and how did the collaboration with artist and musician Francesco D’Abbraccio come about?

Carola Bonfili: I was interested in maintaining a non-verbal narrative that still had the characteristics of a dialogue, or of an exchange, between the little monkey and the surrounding environment. The sound itself has an almost hallucinatory quality within the story, a trait that is already part of its nature as it is interpreted and processed differently by each person, just as visual experience cannot be entirely determined because it is not reality itself. I provided Francesco with a series of information, trying to be as specific as possible, so that he could fully understand the initial intention and then be completely free to interpret it. Francesco has the ability to give a physical volume and to impart tactile qualities to any type of sound.

In his essay titled The Temptations of Saint Anthony and intended as a review of Flaubert’s book, Pavel A. Florensky states “We do not know the substance of reality, we only know its form. But form can be deceptive and illusion is perhaps the only reality. Do we really see it? Do we really live? Or is nothing really there?…”

I find this quote particularly interesting because, while clearly referring to religious experience, it also touches on Platonic and Cartesian insights and literary, cinematic and philosophical ideas that arise (directly stem) from the invention and exploration of virtual worlds, augmented realities, etc. Your work also acknowledges the mystical nature of technology, specifically in virtual interaction…

I am particularly drawn to certain dimensions, strongly mystical or even religious, created by figures such as Flaubert, or Franz Kafka, or, as the supposed author of Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, Francesco Colonna. What interests me about technology is the relationship of continuity it creates, that makes the virtual experience resemble the real one. By continuity, I mean the functioning, how we continuously perceive the surrounding environment, never breaking the field of vision (except for the moments when we blink) in both space and time. And in this, virtual reality, with all its technical limitations, is the only experience that can overlap with the real one. Both are false, only in different ways.

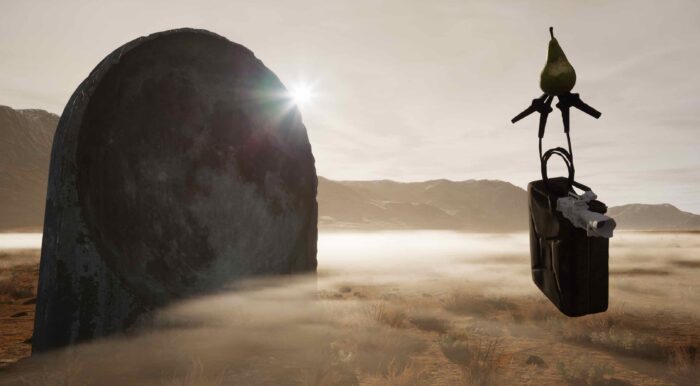

The exhibition, hosted at La Capella in Barcelona and at Aksioma in Ljubljana (soon at Maxxi, L’Aquila) emphasized both the virtual and material nature of your project. Alongside the trailer and the VR, more purely sculptural elements were exhibited, not only to “materialize” the story’s characters (such as M’ling and Tanky Pear) but also to illustrate some processes behind the digital animation technique.

I am specifically referring to The Stone Monkey PBR and The Multicrane, which respectively represent physical renderings used for 3D modeling and a reproduction of the mechanism by which the first Disney cartoons were animated.

What motivated this choice?

If reality can be interpreted, the construction of an object and its functioning seem to have more solid foundations. To understand an object, we observe it, disassemble it, and try to make it work. It is a fairly common attitude that can be framed within a kind of systemizing mechanism.

Specifically, The Multicrane is an analog reproduction of the early Disney animations: a series of overlapping painted panels that gave the illusion of depth. I was interested in building something that I couldn’t completely understand, as if the process would provide me with additional information.

The PBRs, from which I drew inspiration for the six spheres (The Stone Monkey PBR), are the “skin” of the digital matter. Making them physical helped me isolate and highlight those details that seemed important to me. And while PBRs only have different appearances, because they are fundamentally immaterial, the things around us are the result of various combinations of atoms. Perhaps the two materials are more similar than they appear; both show something they are not. Furthermore, the purpose of CGI software, which is also the reason it interests me, is to make digital scenarios as realistic as possible by modeling them in reality: everything works exactly as it does in the real world, even if there is no actual need for it. I wonder if we will ever reach a level of technological evolution where reality is merely the starting matrix, similar to how proverbs or superstitions work, where the expression remains but the origin is often forgotten. Perhaps a future civilization that lives solely in the digital realm, will not be able to explain why an artificial sun stays for a predetermined number of hours, or why an object bends or deforms when touched, or even why throwing a stone into the water causes circles to appear on its surface.

In the The Stone Monkey trailer, we see a summary of the journey taken by M’ling to regain her appearance. However, the brevity of the video limits the deepening of the plot and, especially, of the characters.

While some characters follow the fairy tale tradition (such as the structure of the story itself, which aligns with Proppian functions), others are more enigmatic, such as Tanky Pear or the impressive robot M’ling discovers in the forest.

What is their origin and what role do they play within the story?

In one of the initial versions of the story, the protagonist was a giant robot made of mirrors; I had imagined it as a kind of reflective surface with its own consciousness, an introspective robot that interacted differently with objects in its surroundings. I liked the idea on paper, but in practice I encountered difficulties in realizing the interactions. In the new version it remained only as an architectural presence that hosts a scene from the video within it. Tanky Pear, on the other hand, had almost a consolatory function: I wanted to create an object with which to empathize, a little helper that maintained anthropomorphic proportions. I chose to compose it with a series of objects that seemed to make it believable, but at the same time misleading at a quick glance, and subsequently made it move like an insect, emphasized by Francesco’s audio.

One element that seems to recur in the construction of the characters is the hybridization of natural and artificial: the protagonist’s skin is sublimed into a reflective, metallic surface, similar to the giant found in the forest. Tanky Pear itself is a tank animated by the electricity produced by a fruit that seems to constitute its “brain” or consciousness. Do you think that the use of technology has somewhat shaped the aesthetic of the project and, more generally, of your practice?

In technology, as in architecture, forms are the result of a function. Their aesthetics reflect all the functional steps that were necessary for their construction, conveying a relationship and balance between the parts that is always interesting. In their physical representation, the function has been lost, yet it has been embedded in a type of imagery, just as we have now assimilated new materials that give us more room for speculation.

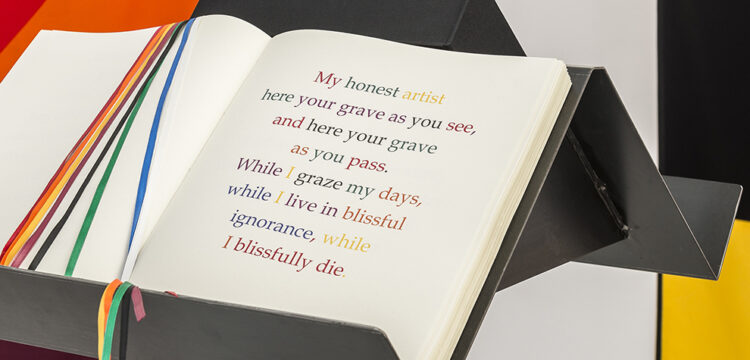

The exhibition catalog, published by Nero Editions, will document the entire project, featuring original texts and contributions by the curators Ilaria Gianni and Daniela Cotimbo together with Domenico Quaranta and Valentina Tanni.

Could you provide an overview of the structure, contents and insights proposed?

We decided together with NERO to dedicate the book’s first section to the video and to structure it like a graphic novel, in order to integrate the textual part.

We conceived it as a narrative entry point that then unfolds into the other sections, where the documentation of the various design phases, images from the exhibition at Aksioma, and finally the texts by Ilaria Gianni and Daniela Cotimbo, the project’s curators, and by Domenico Quaranta and Valentina Tanni, whom I asked for an external contribution, are gathered. The curators’ texts analytically describe the work in different ways. Ilaria Gianni delves into the heart of the project, constructing a precise framework that detailly narrates and contextualizes the historical and ethnographic references that underpin the work, while at the same time illustrating the connections between its parts. Daniela Cotimbo’s text, The feeling of what happens, but doesn’t, introduces a description of how cognitive processes work and how we use them, starting from individual perception to a collective one. Within this framework, she breaks down and details the work, starting from its initial history, which as she defines it herself: is often drawn from pre-existing narratives, and is like an elastic mesh meant to be stretched, expanded, and taken beyond the boundaries of its structure. Domenico Quaranta describes the ongoing intimate tension, almost suspended and fragmented, through which we understand and perceive a reality that is always partial and on the verge of collapse, where antidotes and escape routes are sought–such as the construction of alternative individual worlds in which he inscribes the project by detailing its most essential parts—that can serve both individual and social functions. Lastly, Valentina Tanni’s text is structured almost like interconnected axes sliding into each other, revealing different aspects of the work, and as it delves deeper it unpacks its mechanisms, even the most unconscious ones.