Rewriting History in Cairo

A reflection on language, dubbing, and censorship through the curatorial approach of one of the exhibitions part of Cairo’s Off Biennale

Something Else is a non-profit independent visual arts initiative that attempts to support Egyptian and international contemporary art through an Art Biennale conceived by chief curator Simon Njami and artistic director Moataz Nasr. The first edition of the festival was launched in November 2015 with the aim to propose a fresh and progressive presentation to the Egyptian art scene and to peel off the stereotyped concepts around the role of art in society, by creating a dynamic and fresh space of expression.

The second edition of Something Else focuses on rewriting history or what if it did not happen? Curators and artists were invited to imagine a world that would be something else because history took a different turn, that led us to become something other from what we are now, through a path that would have created another world and other kinds of relationship between human beings. What if art history was not inherently European and if the most contemporary practices were not to be found in London or New York? This edition is an invitation to think out of the box and the occasion to free our mind from the so-called truths we have been fed with. According to the chief curator Simon Njami, the event’s first edition was proposed to go in parallel to the Cairo Biennale in November 2015, but unfortunately it was not the case. The Cairo Biennale never happened and Something Else had to walk alone. The theme of the this year’s Biennale what if it did not happen carries a very cynical undertone.

Downtown Cairo

For the exhibition Dubbed—as part of Cairo Off Biennale—curator Sarah Oberrauch focuses on different aspects of dubbing through the work of the presented artists, namely Pierre Bismuth, Anri Sala, Aslı Çavuşoğlu, Kerstin Honeit and Markus Öhrn. Language is not individual and to speak means to use the words of others. Language reflects a social reality in any given culture. By transferring an original dialogue into a dubbed version an adaptation to the target culture is happening. How far dubbing a dialogue into a different language is changing the original message and how are informations perceived, if they are conveyed into a different language and cultural context? The term “dubbing” refers commonly to the replacement of the actor’s voices with those of different performers speaking another language, in order to make it applicable or comprehensible out of the original linguistic field. But there are expressions that do not find equivalent in the target language. In this case a domestication of the content is happening. Culture-bound items from the originals are replaced with elements of the dubbing language. Dubbing adds something new to the images on the screen, which are then overlapping with the visual information of the movie.

Movies and video works, which are widely perceived as easy traveling artworks, are nevertheless facing cultural and linguistic borders. Originally, dubbing was to control the dialogues contained in the movies, which potentially introduce ideas and ideologies contrary to the totalitarian governments of Europe in the 1930s. In this case, dubbing was pervasively linked to censorship. But the practice of dubbing also helps to distribute and spread mass media, which does bring a subtle form of acculturation.

Pierre Bismuth, The Jungle Book Project, 2002. Courtesy Christine König Galerie, Wien

The movie The Jungle Book Project (2002) uses the homonymous Walt Disney film, but with an altered soundtrack. Pierre Bismuth arbitrarily assigns to each character a different language linked to national clichés and geo-political power struggles. The main antagonist of the Disney story, the bear Baloo and the panther Bagheera, for example, speak Hebrew and Arabic. Mowgli, the boy, who is raised in the jungle by wolves evokes the imperial force of the Spanish Kingdom, which is threatened by the strength of the British Tiger Shere Khan. Beside any historical explanation the songs performed by the characters might give another hint to their nationality, as suggested a marching elephant, which creates the link to the Germanic culture of memory. As Thomas Trummer puts it, French artist Pierre Bismuth, whose work involves language, understanding and the methodic premises of visual expression, has altered the soundtrack of The Jungle Book. Bismuth assigns every character of the well-known Walt Disney film a different language. And yet this confusion of tongues is not able to torpedo the plot: amusingly, it actually brings to light associative classifications, national clichés and discrepancies between voice and personal expression. In the artist words: “I have always been fascinated by how children can watch or listen to the same video or record again and again for days, weeks or months. When, in December 2001, I was looking for a gift for my godchild, I wanted to find out if The Jungle Book could tear her interest away from Winnie the Pooh, which had held her enthralled for several months. The idea was to buy not just one version, rather three or four: Dutch, English, Spanish, Italian etc. I wanted to see how an 18-month-old baby would react, when she always saw the same thing, but heard something else. Before I sent the tapes, I listened to all of the dubbed versions, and I was so fascinated by this experience that I wanted to have every character in a single film speak a different language.”

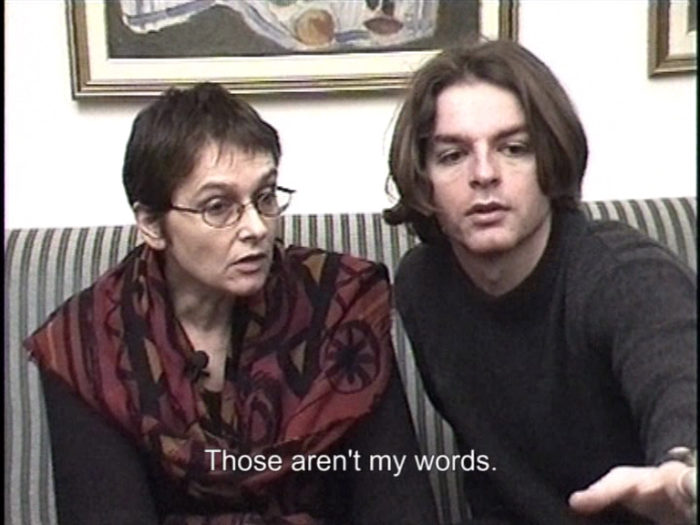

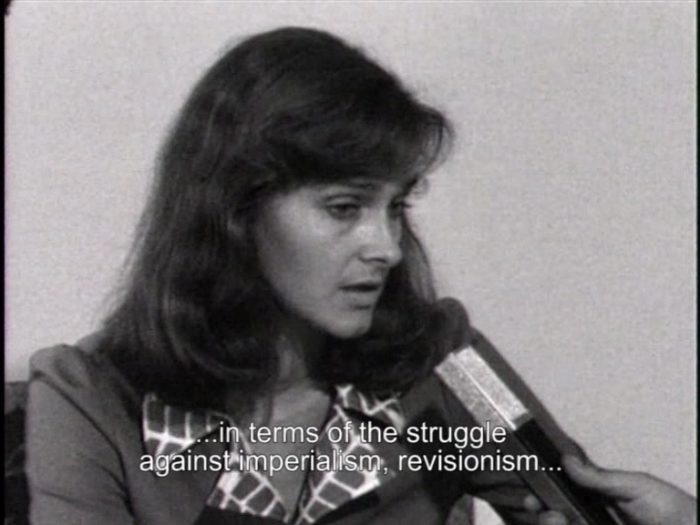

Anri Sala, Intervista (Finding the Words), 1998. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris

As a young film student, Anri Sala found an old newsreel film in the moving boxes of his family house in Tirana. Containing images of a congress of the Albanian Communist Party, in whereas his mother was giving an interview. Although the sound of the reel film was lost, with the help of lip readers, he was able to decipher his mother’s words. Twenty years later he showed the subtitled film to her and confronted his mother with her younger self. Valdet Sala hardly recognized her words in the interview as her own. The words were just echoing the party’s propaganda. The questions as well all the answers were set in advance and foreseeable. In Anri Sala’s film Intervista (1998) his mother, a leader of the Communist Youth Alliance, is seen making a speech, and later giving an interview, reflecting on her personal memories, deeply intertwined with collective ones. With the passing of years the woman had left behind hopes and fears, ideals and disappointments, deceptions and rebellions of her youth.

Aslı Çavuşoğlu, Vinyl, 12“, 45 RPM, Single Sided, Limited Edition, Numbered. Courtesy the artist

In January 1985, the General Directorate of the Turkish Radio and Television Corporation (TRT) banned the use of 205 words on TV and radio broadcasts on the grounds that they did not comply with the general structure of the Turkish language and that they were beneath the level of standard Turkish. While the order was ultimately repealed, it sought to ban words such as “memory, recollection, experimental, revolution, dream, possibility, freedom, and life”—among others. The song 191/205 (2009) by artist Aslı Çavuşoğlu was created with the Turkish emcee MC Fuat and consists of 191 of these banned words.

Markus Öhrn, Featuring Persona (1966) by Ingmar Bergman, VJ HD. Translation by Kenneth Barongo, Subtitling by Stuart Braun Production Markus Öhrn, Swedish Subterranean Movie Company.

In the slums of Kampala-Uganda’s capital, a new unique tradition of live film translation has emerged in recent years: veejays. These are people who work in makeshift cinema halls in slums and remote villages. Their art consists of directly translating the dialogue and explain the plots- as well as various aspects of Western behavior and lifestyle for the local audience. Usually Hollywood blockbusters are shown, but Swedish artist Markus Öhrn came up with the idea of showing Ingmar Bergman masterpiece Persona (1966) in this particular cultural context and documented the event on film. The VJs commentaries resemble an anthropological exploration, deconstructing and reinterpreting white, bourgeois art with great irony. Markus Öhrn allows the European spectator to see how the African viewer looking at him. A confusing reversal that induces us to reflect on our own perspective.

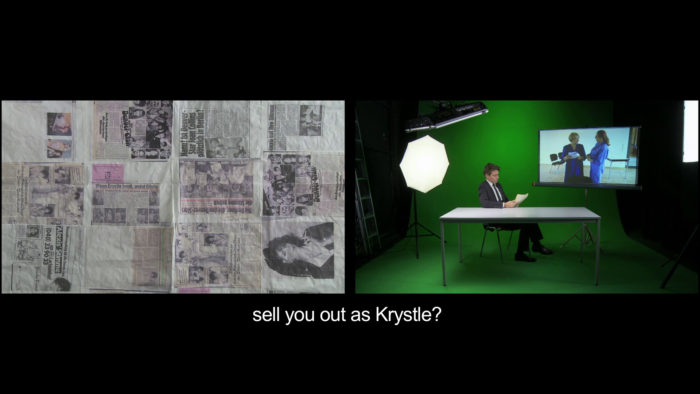

Kerstin Honeit, Talking Business, 2014/2015. 3-Channel Video Installation, Duration 13:00 min. HD colour, sound

Kerstin Honeit’s 3-channel-video Talking Business (2015) looks for the bodies behind the German voices of the main protagonist Alexis and Krystel, from the TV series Dynasty (1981–1989). The actresses Gisela Fritsch and Ursula Heyer were dubbing the voices till they became so strongly connected to their characters, that they had to give up their acting career. This multilayered video not only questions the working conditions of the voice actress, but also the relationship of one’s own words and the role they play. The practice and its hidden shift between representation and self-representation are central in Honeit’s video, exploring how the speech act can be empowering, but then who do you talk for? Talking Business is a further contribution of Honeit’s ongoing analysis on voice and representation.

Markus Öhrn, Featuring Persona (1966) by Ingmar Bergman. Installation view

We were curious about the geo-political implications of the location where this project is taking place, so we asked few questions to one of the curators selected for the Off Biennale, Sarah Oberrauch, about her exhibition project Dubbed and her experience in Cairo.

Can you give us a broader idea of the context in which the project is happening? What is the Off Biennale and how did it came into being? And how was the exhibition project Dubbed included?

The first edition of the Off Biennale was launched in November 2015. Back then the original idea was to complement the official Cairo Biennale. Sadly, the official one never happened, and the Off Biennale become more and more a way to push the government to keep its promises. Considering this, the theme what if it did not happen? becomes a somehow cynical undertone. Obviously, the Off Biennale attempts to pin Cairo on the art field and to pull some international attention to Egypt as a vibrant art producer, but beside this, it aims at creating a space of expression. The exhibition project I curated was just one part of the Off Biennale. I got invited to send a proposal for a contribution to this year’s theme rewriting history or what if it did not happen? Beside the chief curator Simon Njami, we were seven curators (interestingly many from Italy) who all approached the theme from a different perspective.

We’ve found this question very compelling: “What if art history was not European and if the most contemporary practices were not to be found in London or New York?” What do you think about it, and whether you thrive for this shift to happen through your own curatorial practice or on regards to the biennale’s overall framework?

With the exhibition Dubbed I wanted to raise questions about how culture is imported or exported. How do we perceive information and content if they are removed from their original context? It was my way to respond to the overall theme. To reason around dubbing gave me the chance to reflect on acculturation and identity-shaping, and on the role of language.

If the current edition of Something else II will focus on rewriting history or what if it did not happen, what is the vector of the gaze? What is the attempt, to tell stories otherwise left untold or to underline some epistemological trends?

For me the theme rewriting history or what if it did not happen? implies a certain regret. I connect it with the wish to undo something or try to reverse the past. It is always said that the victors write the history, but for example, in the case of the ancient romans, it was themselves to put down on records their own decline. It clearly triggers a reflection on the past and the current state, on missed opportunities and consequences. But I won’t say, to regret it is always connected negatively. I remember when Markus Öhrn talked to me about his project with the so-called azodre. An Italian expression in the dialect of Romagna, meaning “she who rules.” Meant here are the women of the house, solely responsible for running the household, always sacrificing themselves for the family and who are never allowed to have any destructive feelings. In his project, he wants is to give these women an opportunity to perform something they regret. Here, regret becomes a kind of liberation and can be very encouraging to break out from your social role.

Markus Öhrn, Featuring Persona (1966) by Ingmar Bergman, VJ HD. Translation by Kenneth Barongo, Subtitling by Stuart Braun Production Markus Öhrn, Swedish Subterranean Movie Company

Speaking of your exhibition project Dubbed. How did you select the artists and their works? What came before, the curatorial concept or the selection?

For me, the film Intervista by Anri Sala was a starting point to draft the concept. I wondered, considering Egypt, what would be the word said by an Egyptian mother, if someone does a remake of Anri Sala’s film in the context of the Egyptian Revolution? How would the situation look like if it wasn’t set in Tirana, but in Cairo? Less about what is said politically, but the way in which it’s articulated. What would be said differently? At the beginning, it was not clear that the main topic will unfold to dubbing. But rather on reviewing the past from the current state, through a lost female voice questioning issues of representation and self-representation. It became clear pretty soon that there were different aspects of dubbing I could focus on, to open up the conversation.

How does each work speak of this transfer—typical of dubbing, from the original dialogue into a dubbed version, and its adaptation to the target culture where it is happening? What stand do they take in relation to content domestication?

The film Bergman in Uganda from Markus Öhrn shows the transfer of the original dialogue into a dubbed version in its most explicit form. What you see it would probably make you laugh, but at the same time, make you rethink on how we take what the VJs says for granted. For example, when he says—“We are looking for houses to stay in. Over there they have summer houses.” Also, it could never been mentioned that there is a kind of love relationship between the two women since the existing laws in Uganda, criminalize homosexuality and LGBT people face major harassment and intimidation. In this moment things stay untold, because there are no words to express it. Another example might be the video Talking Business by Kerstin Honeit, for the relationship between speaking your own words and playing a role, between dubbing a film star or embodying them. Kerstin Honeit constantly explores the technique of Film-Synchronization and Lip Syncing in her works and examines the coherence with body and voice, as well as the construction of stereotypes and identities. The different nature of languages is not always adequately transferable.

Anri Sala, Intervista (Finding the Words), 1998. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris

As mentioned in the press release, “originally dubbing was to control the dialogues contained in the movies, which potentially introduce ideas and ideologies contrary to the totalitarian governments of Europe in the 1930s. In this case dubbing was pervasively with censorship.” So, what does it mean to bring these works to Cairo today?

Your question is totally eligible. Censorship is a widespread phenomenon all over the world. There are states which practice it more rigorously than others and the strategies to bypass it becomes almost a piece of art by itself. It was not my intention to frame the entire exhibition under this issue, but of course it resonates. Turkish artist Aslı Çavuşoğlu plays with censorship in a very refreshing way. In the work 191/205 she draws attention to the government control of the usage of words. By taking 191 of the 205 banned words and having Turkish rapper MC Fuat turn them into a song, one can move their ass to the beat of censorship, and it becomes one of the most enjoyable ways to release the pressure.

How are the works interacting with the audience and vice versa what’s the audience response?

Egypt had once a very flourishing film industry. The Egyptian dialect is one of the most common language used in Arabic movies and television programs. So, I think there is a wide affinity to this cinema tradition. But beside that, all the exhibited works respond to the topic of dubbing as framed on a more general gaze in regards to language. For example, in the movie The jungle book project by Pierre Bismuth every character is assigned a different language, linked to behavior and attitudes commonly associated to the specific culture. Luckily, one of the main characters, the panther Bagheera, speaks Arabic. But even you don’t understand every word, the context and mimics of the character allow you to easily follow the plot. It doesn’t matter in which language it is and I have to say, and it worked for me very much the same.