Reviewing Dualities

A review of “A Fool with a Tool”: a solo show by Gaia Fugazza

Gaia Fugazza and Giulia Pollicita have decided to realize a hybrid form of review/interview departing from the works presented at Gaia’s latest solo show at Case Chiuse HQ in Milan, touching upon various aspects of her research. Merging Giulia’s reflections with some excerpts of an oral interview with Gaia, they briefly explore together some of the pivotal topics her works deal with, employing a sort of parallel narrative that attempts to explore her practice, from paintings to performances.

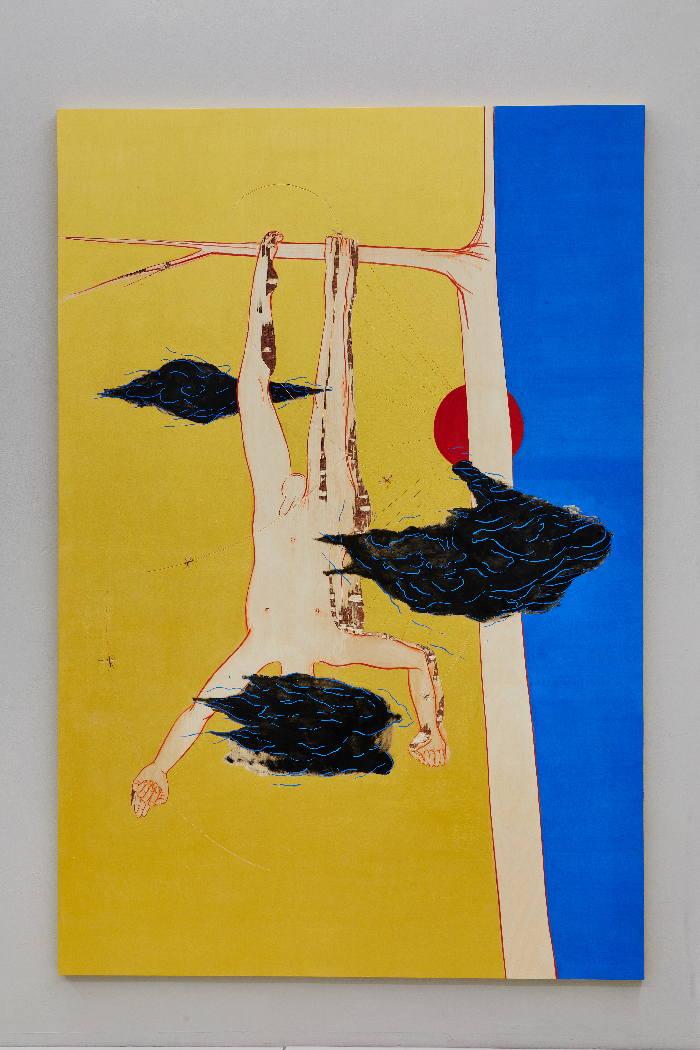

Curated by Francesco Urbano Ragazzi, Gaia Fugazza’s solo exhibition A Fool with a Tool opened on October 19th at Case Chiuse HQ in Milan. The works on show provide an overview of the artist’s research, with symbolic pieces spanning over a decade between 2010—with Quattro Animali, the acrylic on paper that opens the exhibition—and 2021—such as the hanging upside-down man portrayed in L’Altra Stagione, or Frecce, the double swinging panels in stained wood and beeswax, marking the passage of visitors.

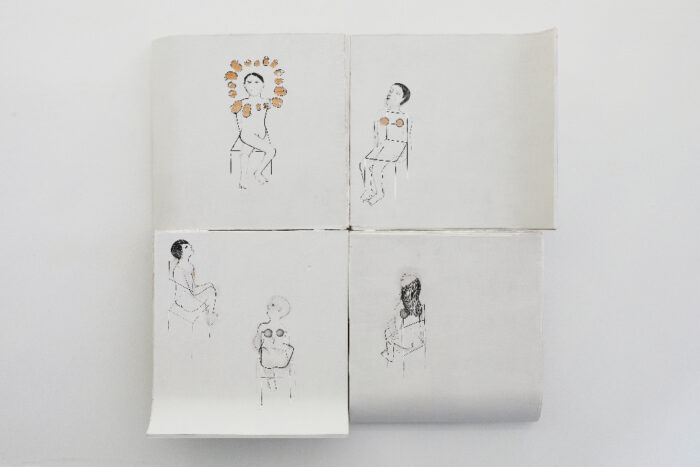

The enigma around Gaia Fugazza’s practice goes back to a misunderstanding embedded in Western thinking, a metaphysics where “man is the sole finite agent and nature a vast system of machines for man to use and modify.” A misinterpretation based on an intrinsic dualism associated with a post-enlightenment consciousness that considers man essentially separated from nature—as well as culture. A notion deep rooted in Western culture and Christian religion, that causes radical exclusion, domination of nature and other non-human beings. Across different supports, media and techniques, the artist employs various materials: from painting on wood to engraving, from beeswax to plaster. This imagery and its complex entanglement with the contemporary are constructed via observation and a meticulous handling of matter. Gaia’s approach to the surface—now engraving—maintains a miniaturist relationship to her figures.

I often understand the reasons behind certain choices of materials as a posteriori reflection, rather than a priori assumption. The materials nurture and compete with the representative part of the work and are part of the figuration. There is also a link to the performative aspect of the work—I mean its realization. Before working on a series, I ask myself how I’ll be spending my days in relation to a certain labor. The technical elements therefore have a symbolic value within the work as well.

What becomes an ethics, or an ecology of knowledge and its representation, is explored by different means and shapes, which altogether attempt to acknowledge the interconnection between the forms of social domination and those towards nature—as essentially bound. Such an attitude sheds light on how social control affects bodies, as well as nature—via an extractivist exploitation—or causes the uprooting of animistic practices of knowledge from contemporary society. The latter is the case of the forgotten properties of plants, to whom the series Virginity is not a Contraceptive, presented last October at the Richard Saltoun Gallery, is dedicated.

At the age of 29, after having two children in two years, as an ecological choice, I decided not to have anymore. I was a bit daunted by the idea that I would have to manage my fertility for so many years to come. As a spokesman for the psychedelic experiences in the Seventies, Terence McKenna was asked in an interview for recommendations to solve the world’s problems. He then asked the mushrooms which gave him a very simple answer: each person should bear only one child. I felt that contraception was something most women deal with on a daily basis, and it is an action with huge socio-political implications, so I felt it deserved an artistic representation.

Rather than addressing universal themes abstractly, in so doing Gaia Fugazza’s research tackles them proceeding from the personal. Casting a situated gaze on reality, the individual transcends the specific and rises to the speculative: just like the dualism between man and nature, the dualism between the particular and the universal is challenged. As Virginity is not a Contraceptive might point out, the communion with nature coincides with a form of awareness both internal and external to the individual. An awareness—or non-awareness—which retains a political significance. The private and the public coexist seamlessly.

As Silvia Federici recounts, in the middle ages, most women would have been more aware of how to control their reproduction than they would have been in the Fifties. This was because a lot of the popular knowledge related to fertility practices, lunar cycles, contraceptive, and abortive methods was gradually discredited and criminalized with the advent of a more Cartesian idea of medicine which was then an exclusively male practice.

From paintings on wood to performances, Gaia’s research represents an imaginative exercise that pictures alternative ways of configuring human presence on earth, composing a mythology of visions, images and apparitions that transfigure the everyday re-elaborating it speculatively. Some settling scenes almost never placed in defined landscapes, but rather in backdrops that appear suspended, the figures emerge as signs of a synthetic representation between lived experience, external event, and storytelling.

Prickley Pear and Carrara both start from an automatic drawing I made while on the phone depicting three vaguely conspiratorial men, confabulating about something, with decomposing and hollow heads. They looked like they held a position of power and conveyed a negative feeling to me. I superimposed the image on two different landscapes. The view over the quarries of Carrara, which embraces the Alps, the sea, and the white quarry—which is both a fascinating and terrible image, an ecological disaster in fact. But as an artist, I cannot also forget the thousands of years of sculpture that arose from these excavations. There are traces of a civilization almost unto itself, paths that lead to the center of the mountain. The view reminds me of all the ambitions we have, all the individual efforts towards aesthetics and visual language. In Prickley Pear the same three figures are superimposed over a portrait of the prickly pear plant in my studio, which transforms and turns in on itself over time and I suspect may have been the unconscious inspiration for the image of the three men with holes in their heads.

In this narrative and representative context, however, there is no interruption nor distance between the knowledge of a plant, their healing psychoactive properties, and an iPad screen (Lots of Choice, 2015) or a self-portrait on a computer (Self-Portrait in Computer Light, 2015, made in collaboration with Haroon Mirza). The point is not to dwell on a primeval, archaic imagery, but to assume a standpoint which avoids dualisms, eliminating hierarchies and disparities among the human and non-human—to the point that this dualism does not make sense anymore. The point is to recast a vision that fluidly contemplates the concept of technology, regarded as a seamless continuity between agriculture, as well as magic and sheer “technic” —as the artist tells me in our interview.

In a way the “tool” in the exhibition’s title is an enigma. It could be the artworks, it could be technology—which I understand very broadly: agriculture is technology, language is technology, just as much as the internet is technology. The central issue is that our body is subject to so many stimuli, reactions, dynamics, in conjunction with our environment, what we do, what we eat, how we relate to non-verbal language, and we can have so much power and potential from understanding these interactions.

A deep understanding of nature brings a disclosure of its power, akin to something beyond it, a somewhat “super nature” —Super Nature in Two Parts is also the title of the event presented by Haroon Mirza and Daria Khan, where the artist took part with the Mimosa Pudica performance at the Lisson Gallery in 2018—that act as a bridge to multifaceted issues. The Mimosa Pudica, for instance, is an uncommon plant particularly sensitive to touch, which retains an instantaneous reaction anytime its leaves meet external bodies. Also known as “shy plant”, or “touch me not”, it has been described by botanists drawing upon feminine appellatives and adjectives that call attention to the often-common epistemology of passivity and submission attributed both to women and nature by Western male gaze.

In the performance Mimosa Pudica, porcelain casts of contraceptive pills are offered to the audience to hold in their mouth. Probably half of the audience (women) know what this specific pill is: very small, rounded, extremely easy to swallow, slippery and elusive. It seems to be shaped for you not to even notice you are taking it. In the performance these sculptures are a tool which work on the attention the audience needs to make to not swallow them, thus noticing the body’s automatic movements. In the meantime, I tickle the leaves of the Mimosa Pudica with my tongue. Rapid movement is unusual for a plant. Movement is often thought as the main difference between the vegetable and the animal realms. This characteristic has fascinated naturalists, biologists, who have imagined that Mimosa Pudica might have emotions, or communicate. The roots of this plant are used in Ayurveda both as an aphrodisiac and as a hormonal contraceptive especially effective on men. The plant has such beautiful popular names: “shy plant”, “shame plan”, “touch me not”. All adjectives almost describe a woman who is a little bit shy, repressed, demure. During the performance I first close all the Mimosa Pudica leaves with my mouth, then play percussion through aluminum bracelets by shaking my arms and turning, this part recalls various techniques of transcendence. I wear a chaste outfit: black turtleneck, with a long-painted skirt. When I raise my arms and the bracelets are silent, I drop a porcelain egg from inside. While making this performance I was thinking that in the past, people may have gone to the same person both for tripping or to get an abortion.

The same relational force stigmatized by the Mimosa Pudica and its “reluctant” behavior, is challenged by the foreign bodies offered by the artist. Whether individually molded ceramic sculptures of nipples, octopuses’ beaks, or tiny contraceptive porcelain pills, we are invited to relate to art works as a way of exploring our bodies as ever-changing entities. At the Lisson Gallery as well as at the Royal Academy performance in 2019, while the artist tickled the reaction of the Mimosa Pudica with her tongue, the viewers were forced to concentrate on not swallowing, having the presence of small sculptures inside their mouths.

An element of observation linked to the everyday always returns—whether it be the smallness of contraceptive pills, or the familiar vision of a landscape, as in Carrara. Gaia’s works seem to echo a trait usually attributed to South American literature, that of a sort of animism where there is no separation between the particular and the universal. Just as there is no contrast or interruption between life and death, living and inanimate beings, humans, and the animal kingdom. In the artist’s imaginary, the world thus seems somehow transfigured through the lenses of a fairy tale that tells via metaphors the complex power dynamics affecting the world. If the point is to avoid the split subjectivity of capitalist society, on which the entire extractive project of modernity is established, the turn to take is towards the construction of new subjectivities.

Lately I have been reading Jodorowsky’s Where the Bird Sings Best, in which he looks at the history of his ancestors as a mythical story. I have an affinity with this type of storytelling, in which the everyday becomes archetype. In my work I’m inspired by something I’ve noticed in my daily life, but when it becomes an image, it is not anymore what happened to me, but what happened to me and will happen to thousands of other people. It is like being part of a continuous becoming, where our individual episodes will happen to others. It is never just my experience. I’m currently reading On the Iliad, by Rachel Bespaloff, which looks at the epic text as a fairy tale, without judgment. Things happen anyway, fatalistically. And what is the force that generates these events, we are not given to know.

The insistence on ritual, understood as a subjectivity in constant definition in tune with the collective, becomes central to such a task. It is the element of rituality—whether modern, natural, or technological—that constitutes one of the pivotal concepts addressed by the artist, from the material to the performative expression of her practice. It is not by chance that the “world of childhood, amorous or political passion, and of artistic creation” are characterized by “aspects of polysemic, transindividual, and animist subjectivity” capable of undermining the ontological dualisms embedded in modern thought. The same effort striving to cancel the dualism between man and nature, the everyday and the universal, knowledge and nature, punctuates Gaia Fugazza’s work.

There is a specter in this exhibition: I think that over time, without me looking for it, it is as if the hanging man of the tarot has found me. Until now, because of a bad experience with a friend, I’ve purposely avoided knowing anything about tarot. In the last two years, I’ve made three different versions of a man hanging with his feet from a tree, and gradually it looked more and more like the hanging man. This made me curious about tarot but so far, the only thing I want to retain is the communication transmitted directly from the image.