Resounding Voice(s)

A cross-exploration of the artist interview as a medium

The Entangled Interviews Project is conceived by Chiara Ianeselli; an artist interview conducted by the author is juxtaposed with extracts from other interviews selected from art journals, oral archives of museums, catalogues or other forms of publications. This project aims to highlight affinities and affiliation or contrast of the interviewed artists with other positions. The questions resemble each other in the form or in the content of the answer. In this case, the interviewed artist is Oscar Santillán.

WHY INTERVIEWS?

“My Dear Mr. Bok,

It is like most interviews, pure twaddle and valueless.

For several quite plain and simple reasons, an ‘interview’ must, as a rule, be an absurdity, and chiefly for this reason—It is an attempt to use a boat on land or a wagon on water, to speak figuratively. Spoken speech is one thing, written speech is quite another. Print is the proper vehicle for the latter, but it isn’t for the former. The moment “talk” is put into print you recognize that it is not what it was when you heard it; you perceive that an immense something has disappeared from it. That is its soul. You have nothing but a dead carcass left on your hands. Color, play of feature, the varying modulations of the voice, the laugh, the smile, the informing inflections, everything that gave that body warmth, grace, friendliness and charm and commended it to your affections—or, at least, to your tolerance—is gone and nothing is left but a pallid, stiff and repulsive cadaver. […] It can convey many meanings to the reader, but never the right one. To add interpretations which would convey the right meaning is a something which would require—what? An art so high and fine and difficult that no possessor of it would ever be allowed to waste it on interviews.

[…]

If you wish to print anything print this letter; it may have some value, for it may explain to a reader here and there why it is that in interviews, as a rule, men seem to talk like anybody but themselves.”—Mark Twain, “Letter to Edward Bok” December 1888, in The Complete Letters Of Mark Twain, Albert Paine 1917

Chiara Ianeselli: Oscar, once it was common to ask one’s job at the registration at a hotel, what would you write?

Oscar Santillán: Speedwalker.

When did you first become aware of art? Which is your very first work?

I was raised in a small city, not a beautiful one, in the tropics of Ecuador. In town there were only two monuments; one was a giant pineapple, the other was a lion with its legs way too short. No heroes in town, this is perhaps the only aspect I liked of it.

The public school I attended was mediocre but my mother compensated those deficiencies by schooling my siblings and I in the afternoons. She encouraged us to read although she mostly focused on mathematics. I was raised in a wonderful environment, at home we had a large backyard which every year in the rain-season was flooded by the nearby river. You could open the house door, come down a few steps into the backyard and walk with the water raising all the way up to your belly, surrounded by fishes, dozens of fishes. There was such simplicity, during those years I experienced reality in some sort of pristine sharpness. Back inside the house, on some walls you could admire wooden cases displaying the collection of taxidermy butterflies which my father had captured himself, one by one, and carefully classified. I became aware of art because I was fortunate enough to have these parents. There is no tradition of the humanities in my family, but art was there as a force which didn’t need to be defined.

Hans Peter Feldmann and Kaspar König in conversation in Frieze, November 2011, reported in Frieze, January 2019

KK: Mr Feldmann, it used to be customary to state one’s profession when checking into a hotel. What would you write?

HPF: Mostly ‘merchant’, because for over 30 years I really was a merchant. Sometimes ‘photographer’. Because photographers are always very welcome. Everyone likes being photographed and looking good.

KK: But what about checking in as an ‘artist’…

HPF: No, I’d… I’ve never done that. No.

KK: But there’s no doubt that you are an artist.

HPF: To be quite serious: I’m not entirely sure. Because it may be that I only play at being an ‘artist’ to have access to a milieu that’s closer to me than that of, say, engineers or truckers.

KK: You’ve been doing what you do for forty years now. The fact that you do many things differently to the way they’re usually done in the art business—like not signing your works—has earned you admiration. How do you deal with that?

HPF: I only experience this admiration in a very peripheral way, when it’s there at all. But I couldn’t go and do something just because it’s the done thing or what people expect. The same applies elsewhere too. I try to do only things I think are right.

KK: Much of what you have done has been independent of the art business and independent of commissions. Presumably, this also means that you’ve had to keep your head above water with other sources of income.

HPF: Before the 1980s, practically no one could live from making art and no one expected to. So everyone had to earn their money somewhere else. And if there was no art scene, then I would still cut out pictures and paste them down somewhere.

KK: I doubt that.

HPF: I was already doing it as a child.

KK: Yes, but of course you do it with a different degree of reflection. I mean, you publish these things…

HPF: Some I would never publish. They would be too personal.

Cuerpo de Agua, 2018. A stranger’s left footstep gathered on one side of the pacific ocean, and a stranger’s right footstep gathered on the opposite side of the same ocean. Santillán’s response to Ono’s invitation to take part in her “Water Event”

So, what are we talking about, when we talk about your art?

I think of art as behavior rather than a cultural tradition. To me, art seems to inhabit a territory connecting symbolic thinking, tool making, and innovation. These three characteristics can be found in other animals as well, they are not a sign of any sort of cultural uniqueness on the side of homo sapiens.

The history of art usually has its purported beginning with cave paintings. All the evidence (circa 2019AD) indicates that the oldest cave paintings known were not originally created by us humans but rather by Neanderthals. So, even the history of art doesn’t kick off with human ingenuity.

“Interview by EC with Stanislav Kolibal” in Flash Art The International Arts Review, n. 74-75, May-June 1977, p. 36

EC: What do the light surfaces and strings that you work now with mean?

SK: You think they mean something? No, they are not signs in the sense that they represent something real. They have their inner logic.

What role do chaos and chance play in your work? Is everything so well controlled and thought as it seems?

Imagine a swirl of chaos which gets slower and slower until it stops. It preserves its messiness but in perfect stillness. Then, it can be carefully observed and, finally, a detail within this paused-chaos is revealed.

Vito Acconci interviewed by Jeff Weinstein, The Museum Of Modern Art, January 17, 2012. From the MoMA Archives Oral History, The Museum of Modern Art, Oral History Program

JW: “The Following”, yes.

VA: Yeah.

JW: And what form did that record take?

VA: Not photographs. I took notes as I was following a person, which seems hard to believe now. How could I have done that? But yeah, the only way it’s, quote, “represented” or kept is, each day is described as such and such a time, person in red dress walking down Morton Street, and then goes to a certain store, whatever. And I had set up that I had to stop when someone went to—I could possibly go into a store, but I couldn’t go into a kind of private place or office building. So that Following episodes ranged from, say, two- or three-minute episodes when someone got into a car and I couldn’t follow.

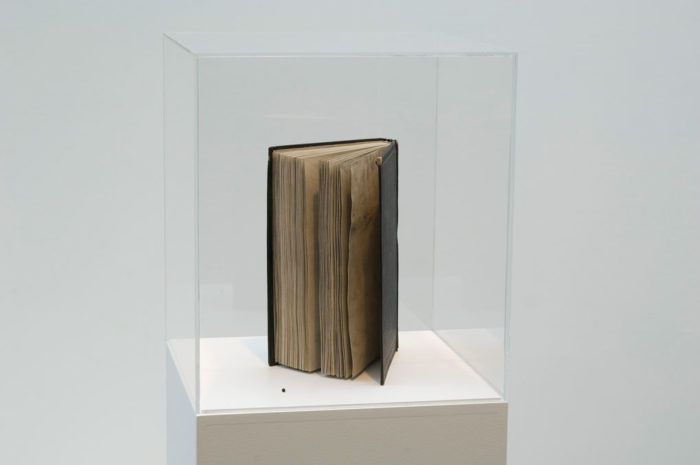

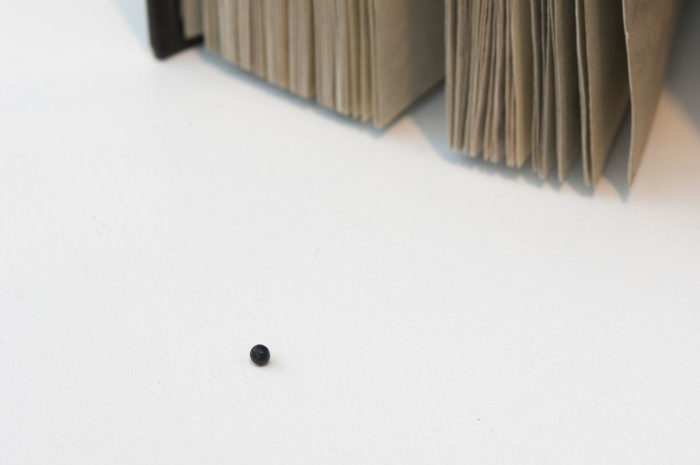

Lost Star, 2012-2013 / A 19th century edition of Alexander von Humboldt’s “Cosmos” treated with a chemical process that has removed the printed ink from the paper, rendering it blank. And, the removed ink turned into a miniature sphere.

Do you think that the labels you are currently using to classify different groups of works, labels such as “Ghost touch,” “Text brought to life,” or “Anima animals,” help people understand your work, if so, how?

Keep in mind that I pursue with my work anything which is interesting to me, rather than a consistent set of topics or mediums, therefore my approach has the risk to be perceived as a bunch of whimsical entities rather than as cohesive reflective clusters. For instance, one project may involve meteorites and neuroscientists, and another philosophers and dancers. As much as I have to give myself the freedom to embrace my curiosity, I’m also taking onto the responsibility of reflecting upon the connections within this diversity of impulses. I don’t see these labels as poetical gestures; they are a pragmatic attempt meant to determine territories of commonality in my practice.

Yvonne Rainer interviewed by Connie Butler, July 7, 2011. Transcriber: Janet Crowl, from the MoMA Archives Oral History, The Museum of Modern Art, Oral History Program

CB: That part of your strategy, you think of as one of collaging.

YR: That’s true. Or, I always use Susan Sontag’s term “radical juxtaposition,” placing things that are incongruous or don’t seem to go together, pushing them together and seeing what happens, like language and movement.

What is the harshest critique your work has received?

At a studio visit back in 2010, during my masters, a professor who I deeply admire told me “you should let your work be smarter than you are.”

Interview with MacChesney (1913), in Matisse on Art(1995) edited by Jack D. Flam, p. 51

HM: […] I do not literally paint that table, but the emotion it produces upon me.

MC: After a pause full of intense thought on my part, I asked: But if one hasn’t always emotion. What then?

HM: “Do not paint”, he quickly answered. “When I came in here to work this morning I had no emotion, so I took a horseback ride. When I returned I felt like painting, and had all the emotion I wanted.”

You seem to always have resisted the temptation of shortcuts, always undertaking time-consuming and technically complicated research. How do you resist to fiction?

Nowadays, due to the overflow of so called “fake news” and “alternative facts” there is a strong craving for a clear-cut distinction between truths and lies, between facts and fakes. Rather than seen this problem as a line with two opposite ends, I see it as a triangle with three vertices: truth, lie, and fiction. I’m curious about the distinction between truth and lie, and between truth and fiction, but I’m even more intrigued by the area between lie and fiction. I’ve come up with the term “pseudofiction” to somehow give a name to this area. However, I still have to properly define it and experience it.

Calvin Tomkins, Marcel Duchamp: The Afternoon Interviews, Badlands Unlimited, 2013, 951, Kindle Edition

CT: Do you feel that science takes itself as seriously as art does?

MD: Science is so evidently a closed circuit, by which you add something to the premises and call it science. But we don’t know the half of it. Every fifty years another law is discovered and it goes on and on. I don’t know why we should have such reverence for science. It’s a very nice occupation, but nothing more. It has no noblesse to it. It’s just a practical form of activity, to make better Coca-Cola and so forth. It’s always utilitarian. In other words, it hasn’t got the gratuitous attitude that art has, in any case.

Lost Star, 2012-2013 / Book, solid ink miniature. 2012-2013 (detail)

Philosophy, histories (not History) and myth play an important role in your research. Are these aspects part of your daily life?

Active imagination or daydreaming are overly present in my life, although I deeply wish that my attention span would be longer. Although daydreaming has the negative reputation of being a retrieving quality, which keeps you away from engagement, I see it as a way of coping with life: daydreaming is a non-reactive strategy to engage with reality.

Willoughby Sharp, “Lawrence Weiner at Amsterdam,” Avalanche 4, Spring 1972, 67, 72.

WS: What does the photographic image of this work [A Square Removal from a Rug in Use] mean to you?

LW: Nothing, absolutely nothing.

WS: What experiences led you to want to deal with language as an art problem?

LW: None of your business. […]

WS: The general concerns of your work have often been referred to as con ceptual. How do you relate to that category?

LW: To be terribly frank, I don’t understand it at all.

What kind of literary authors influenced your work?

Lately I’ve been touched by the fictional writings of Pola Oloixarac, Stanislaw Lem, and Kurt Vonnegut. Although, perhaps the strongest influence comes from scientists, historians of science, and anthropologists; Frans de Waal, George Saliba, and Marisol de la Cadena have certainly shaped my worldview.

Who are the artists you have looked at or that you are currently looking at?

I specially play close attention to the works of friends who I admire such as Martín La Roche, Taus Makhacheva, Haseeb Ahmed, Isabelle Andriessen, Nicolás Lamas, Luisa Ungar, Lantian Xie, Claudia Martínez, Jungki Beak, among many others. And, more prominently, my own thinking process is constantly influenced by the work of my partner, artist Vibeke Mascini.

Complete transcription of the interview with Lucio Fontana at his home in Comabbio, 19 July 1968, published in the editorial version in Domus, n. 466, September 1968

LF: It’s not like I was piercing to break the canvas, no! I was trying to find…Excuse me if I speak like that, today I can say it, because after all it was my ideas…they never understood it – ‘he breaks the canvas’, ‘he does the informal’, ‘he destroys’ – ‘But it’s not true!”[…] Pollock did things after the Spatialists…I say the Spatialists, not me, because Crippa had done the “threads” and “threads” of Crippa in 1950 are very important…Pollock has thrown some color on the canvas, he also with the new dimension, a space, but he made post-impressionism because he threw color, but at the end he threw it on the canvas.

Are you a collector of any kind? Stories?

I’ve been lately collecting old phone-answering machines, the ones which recorded the incoming messages on tape. I’m captivated by those messages which have outlived the messenger, as if their fulfillment remains unresolved.

Unidentified, “Pop Art? Is It Art? A Revealing Interview with Andy Warhol”, December 1962, published in Kenneth Goldsmith, I’ll Be Your Mirror: The Selected Andy Warhol Interviews, Da Capo Press, 2004

QUESTION: What do your rows of Campbell soup cans signify?

AW: They’re things I had when I was a child.

Solaris, 2017 / Photographic lens made from melted desert sand, accompanied by a printed photograph, taken through that lens, at the same desert where the sand comes from

Would you better see your work exhibited in a historical context or in the rather contemporary white cube? Where do you feel it is more proper if anywhere?

Both cases have their own appeal. A historical place, such as a museum, offers perspective to the objects and the viewers; an object displayed in a museum participates in a historical continuum pointing to the different “inner” clocks of each entity in the world.

The problem I have with the white cube is not its isolation from the outside world, it’s rather than its isolation is not radical enough. The aim of the white cube is not the make-belief that the outside world can be erased, but rather than the outside world and its loud messiness can be paused in order to observe something with care. For the white cube to fully reach its legitimate goal some other elements are to be added in addition to its architectural attributes: the blood pressure of visitors must be balanced at its optimum average, cellphone signal shall be interrupted, distracting smells must be avoided (smells of a freshly painted wall are alright since they are self-referential), and visitors should express gentle manners without being too friendly to one another so to remove tensions without engaging in distracting chitchatting.

Achille Bonito Oliva, “Gino De Dominicis”, in Enciclopedia della parola. Dialoghi d’artista 1968-2008, Skira Editore 2008, p. 267, Interview conducted in Rome. 1992

ABO: Does space exist?

GDD: No

Would you say that your work reflect your personality?

Who I am and what I do are part of a continuum.

Bob Colacello, “Andy Warhol’s Life, Loves, Art and Wavemaking”, published in Chicago Sun-Times, Sunday, September 28, 1975

BC: What does life mean to you?

AW: I don’t know. I wish I knew

If today you were not an artist, what would you be?

I would like to be a dog, at least one of the dogs at my parent’s. When I was growing up, every day I had to spend a few hours doing senseless homework. I always tended to procrastinate and would go out and play with the dogs in the backyard. “They have a better life than mine, they don’t have to do any homework!” I used to think, and all indicates that I was right.

Achille Bonito Oliva, “Enzo Cucchi”, in Enciclopedia della parola. Dialoghi d’artista 1968-2008, Skira Editore 2008, p. 267, Interview conducted in Rome, 1982, p. 227, translated by the author.

ABO: Then a separation between art and life?

EC: Painting is one thing, life is another matter. After all do not you remember that Titian was a usurer in life? His direct relationship with everyday things was lending money as a loan shark. Painting was in another dimension. Only in this century one tends to confuse the individual man and the artist. The artist is a completely different person because his work is exclusively tied to talent. And the talent can cohabit with the usurer, the bandit, the common criminal … Because talent is not tied to any kind of moral quality. On the contrary, it must be totally devoid of it. It must have a degree of zero sensitivity with respect to the normal things of life, of civil things, in a certain sense. Talent is amoral. It does not need neither virtue nor moral quality.

What are you currently working on?

Since 2017 I’ve been tracking down episodes of the History of Science in Latin America, and consequently taking this research as the igniter for my own work.

The first episode of my series was titled Solaris, it was done at the mythical Atacama Desert, in Chile; a project which combined Andean cosmology with Soviet science-fiction.

The second episode is titled Light Becoming Land, it retraces the very first Latin American scientific expedition, which consisted of a group of Mexican astronomers who in 1874 travelled to Japan to conduct observations of a rare event, the passing of planet Venus as it perfectly transited between the Sun and Earth. Departing from this story, and further research involving astrophysicists, we’ve been able to replicate the exact chemical composition of the soil of planet Venus, and then this extraterrestrial soil has been turned into ceramics.

The latest episode, brings attention towards the “khipu” system, which is an ancient notation system—perfected by the Incas—a tactile system for writing and accounting, which the Spanish rulers banned at the end of the 16th century provoking it to decay and finally disappear. I see this system as a predecessor of modern cybernetics, or even a parallel history of coding, programming, and reality, which has been lost.

Nicholas Serota, “Gerhard Richter: Panorama”, edited by Mark Godfrey and Nicholas Serota (Tate Publishing, 2011). © Tate 2011

NS: You talked about the fact that sometimes you don’t paint. You have periods when you are not painting. Is this because you are looking for a subject or because you have doubt?

GR: Yes, I’m in one of those phases at the moment, and I’m not sure if I’m just looking for distractions, working on exhibitions and so on, so that I have an excuse not to be painting just now. Or whether I’m looking for these distractions because I haven’t any ideas any more. No doubt it’s a bit of both. There are nicer situations.

NS: Sometimes you need the distraction to get through the day.

GR: Yes. You can’t always work properly. The only really disturbing thing is the fear that it might already all be over. Every time. That nothing more will come.

Solaris, 2017 / Photographic lens made from melted desert sand, accompanied by a printed photograph, taken through that lens, at the same desert where the sand comes from

Would you tell me more about Cuerpo de Agua, a recent work coauthored by you and Yoko Ono?

Since the 1960’s Yoko Ono has been inviting different artists to participate in her “Water Event.” The invited artist is asked to create “a container for conceptual water.” The outcome proposed by the artist is labeled as a collaboration with Yoko Ono. Last year I was invited by Agustín Pérez and Gunnar Kvaran, the curators of her retrospective show Free Universe, and by Ono to take part in the exhibitions in Quito and Lima. Cuerpo de Agua is my response to this invitation.

As you can imagine this came as a surprise and an honor since I consider her to be one of the bravest and sharpest artists of our time. I wish I had the opportunity to meet her in person but that hasn’t happened so far.

Going back to the work, for Cuerpo de Agua I went to Japan, to the shore in Yokohama, where I collected the left footstep of a stranger; then I went to the opposite side of the Pacific Ocean, to Ecuador, and there I collected the right footstep of another stranger. The final work consists of the two small mounds of sand with the corresponding footstep imprinted on each, brought together, placed next to each other. I wanted to create a correspondence between two far away places, to shrink distances emphasizing the inevitable universality of life, the likeness of strangers.

John Gruen, The Artist Observed: 28 Interviews with Contemporary Artists, Chicago, A Cappella Books, 1991, p.82.

QUESTION: Would Martin have liked being a part of the Abstract Expressionist movement?

Agnes Martin: “I’m afraid I wasn’t in the running,” she said. ”But I do place myself as an Expressionist. The fact is, I don’t believe in influence. I think that in order to be an artist, you have to move. When you stop moving, then you’re no longer an artist. And if you move from somebody else’s position, you simply cannot know the next step. I think that everyone is on his own line. I think that after you’ve made one step, the next step reveals itself. I believe that you were born on this line. I don’t say that the actual footsteps were marked before you get to them, and I don’t say that change isn’t possible in your course. But I do believe we unfold out of ourselves, and we do what we are born to do sooner or later, anyway.