Remaking of Histories

A conversation with Frida Orupabo

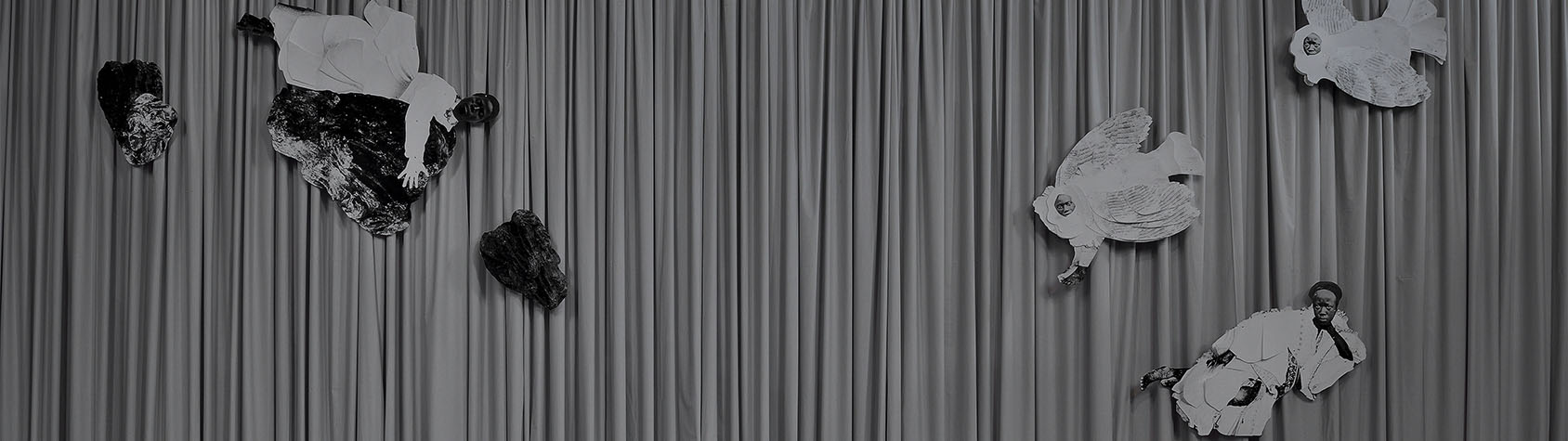

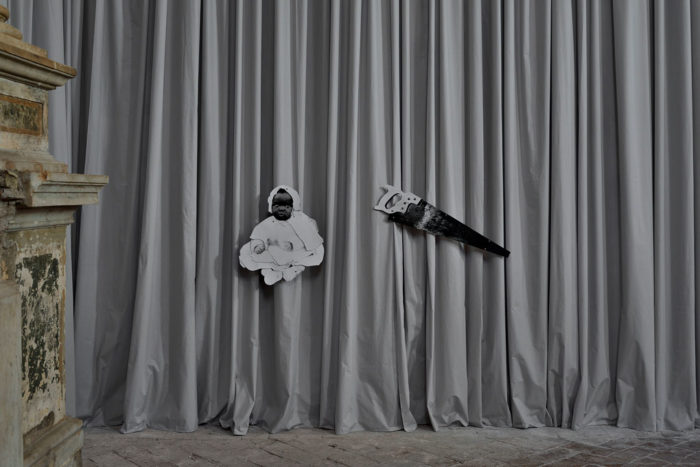

Frida Orupabo’s artworks denude and dismember the multifarious legacies of colonialism, controverting its still-engrained narratives of race, gender, and ownership. Historical photographs of black women provide her not only source material and subject matter, but first-person narrators as well: there is identification between the artist and the figures that appear in her works. The hierarchical relation between subject, viewer, and author—the latter two of which roles have been historically denied to black women—is destabilized, distinctions between the positions blurred, reframed, and upended. The exhibition titled 12 self portraits sees her abandoning the squared-off picture plane, opting instead for free-floating forms—some hung on the wall, others presented as free-standing sculptures.

When looking at Frida Orupabo’s works in space, cohabiting and facing real bodies—being my body among and one of them—one has the feeling of having the chance to walk into some sort of intimate scenography, where collective minor histories are intertwined with personal stories and feelings. This is the first time that the artist’s collages are taking up space, or leaving the wall, that dimensions are used at their full potential. Yet, one can see the lineage that brought the artist from her Instagram account to this tridimensional installation, how the image inflated slowly, grew in scale and gained physicality, yet remaining faithful to its initial urgency. The care that transpires from Orupabo’s work, in the meticulous assemblage of components, which are in fact lines of a story, is simultaneously the keepsake of layered histories and the beholder of a new propositional narrative. A narrative that does not want to—and simply can’t—bend to easy definitions. This daily exercise of care (observing, selecting, cutting, reassembling and layering) clearly happens organically, as a natural gesture stemming out of a thinking process done through the visuals. The figures are morphing into possibilities that refuse any easy definition. As if—to use Audre Lorde’s words—“there are no new ideas, there are only new ways of making them felt.” In Orupabo’s work, feelings are shaping ideas, leaving space for the viewer’s feelings to recompose their very way of looking. I met Frida a few weeks before the opening, when she came to Rome to prepare for the show. This conversation took place before the works came to exist.

Frida Orupabo, 12 self portraits, 2020. Courtesy of the artist & Gavin Brown’s enterprise New York / Rome. Photo: Roberto Apa.

Giulia Crispiani: How are you today?

Frida Orupabo: I am good, happy to be in Rome, and meet the people I am going to collaborate with, who will make the sculpture happen, and so far it has been great.

That’s a new experience right, with sculpture?

It is indeed. Before that I have been working with paper in my apartment, where I have full control. Now it feels like I am losing a bit of this control, as some works will be produced in New York and others will be produced here—and production won’t start until I go back home, and only have photos to look at to make decisions. So, I am very excited and happy to meet up with the people and see the gallery space, which is beautiful—also, I imagined it as a much bigger space, although it has high ceilings, is quite small and I love small spaces, they make me feel warm and cozy. I have the feeling it’s easier to place a work, or to have the works communicate with each other.

Frida Orupabo, 12 self portraits, 2020. Courtesy of the artist & Gavin Brown’s enterprise New York / Rome. Photo: Roberto Apa.

Frida Orupabo, 12 self portraits, 2020. Courtesy of the artist & Gavin Brown’s enterprise New York / Rome. Photo: Roberto Apa.

From Instagram to paper to sculpture, what happens to the image as it takes up space and in case of videos when it takes up duration or repetition? How was the process—for you to move between these three media?

From my laptop—or Instagram to actual physical work, the process was somehow forced when I was invited to participate in Arthur Jafa solo show in 2017 and had to deliver something. Everything I had made before was digital, so I came across the idea of printing things out. In the beginning was in fact just a matter of delivering a product that could be shown and seen in a gallery context. Afterwards, when I saw the work in space, I could see that the dialogue intensified because of the human sized figures. When you enter the space and see the actual work you’re standing and looking into the eyes of a person, like we’re doing now, and this is really creating a bond, intensifying the message and the dialogue, which is something I could not see so clearly before when looking at my Instagram. I have many of the same images from the archive, I even posted a couple of my collages made digital there, but you never get the same feeling of course. That is something I have been thinking about a lot. It has been useful also when considering what type of archive I am making use of, these colonial archives with images which are often hard to look at. I was also afraid the first time I showed them, and still, I can have some thoughts around it—am I challenging the gaze? Am I creating a new narrative? Or am I actually contributing or just reproducing the same narrative as the colonial archive? So I was happy to see that, in a way, it was even more powerful for me to play with the gaze that exposes the viewer as well—you’re forced to see but you’re also seen, and that is a very essential part of my work.

In the case of sculptures, they take up space in a different way…

Yes, absolutely. You are also placed among the works, not only coming into a room viewing the work, but the work will be behind you, around you and it will also, not only create a dialogue between the viewer and the work, but also between the works themselves and those on the wall. In this case, it will be a combination of paper collages on the wall and sculptures.

Frida Orupabo, 12 self portraits, 2020. Courtesy of the artist & Gavin Brown’s enterprise New York / Rome. Photo: Roberto Apa.

Frida Orupabo, 12 self portraits, 2020. Courtesy of the artist & Gavin Brown’s enterprise New York / Rome. Photo: Roberto Apa.

Then this might be the right moment to ask this question because you say “I do not see myself as an artist” so how do you deal with the art world?

I think I try not to, yet I found myself in it and have to. I am still trying to figure out how to balance, how to do the things I want to do and feel comfortable with, and maybe say no to what I am not comfortable with. One example is, for instance, not to work when I don’t feel like or just to produce things for the next show, I want to be able to say no—because then it would be just “producing to produce.” This is one strategy: I feel I should protect the feelings I have towards what I do, which have been so important. I have never produced to show, until 2017, I’ve always done it for my own sake. When I got back home from work, I was doing this to stay sane, like some sort of therapy, to get it out without speaking, because for me to speak and to write has always been difficult. This has been my way and I want to keep it as such, I don’t want to lose this relationship to my work. Even though I think it’s difficult to be in the art world, I have to admit that I am in it and stay in it, I could have chosen not to but I did. Obviously, I also appreciate being able to work with something I love that brings you food on the table and the opportunity to share it and have all these beautiful conversations around it. It is always good to be eye to eye with people, meeting in person with others who might see things as you do—or as totally different.

Frida Orupabo, 12 self portraits, 2020. Courtesy of the artist & Gavin Brown’s enterprise New York / Rome. Photo: Roberto Apa.

In your collage process I see how you select—I would say almost vivisect, from a multitude of images as if you would have a body of images—a specific section and you add it to others—layering, compiling and composing and you pick out what we should see, what stands out on the foreground. As if you would extract a line from a story to compose another one. How does this have to do with healing?

When I work, I work with things that are highly personal but also somehow linked to a history and something political—meaning something that is bigger than yourself and your small life. I am balancing through all these levels, I am communicating with myself but also eventually will communicate with other people who can recognize things that for me are highly personal but eventually might reflect on their own experience. It’s not only about someone else’s gaze, with my work I am also trying to challenge myself and the way I see and think about different topics, such as race, gender, sexuality—what is a feminine body, what is masculine body and do we define that and what are the consequences of that definition? Since I believe that the dominant views, perspectives or narratives on certain topics need to be questioned, and to question is the starting point of liberation, or healing—not taking things for granted. That is also a part of my other study, with sociology, where the main focus is to question what we take for granted so that we can move forward. Also my attempt is to present a reality I feel more real, that can bring in complexity, beyond what’s good or bad. I think this duality comes from my Christian upbringing, I grew up hearing that some things are good and some are bad, as if there’s nothing in between, and that has always been very choking and destructive for me.

Arthur Jafa referred to you and to your instagram alter ego as “a dancer” (an image I love) and “a voluptuous trail of black continuity.” I do love both definitions especially when considering black history—or histories, as histories of violence and absence. It makes me want to imagine possible ways of sewing up, stitching up pieces into a new narration, between past and future, past and present, while dancing—fixing while dancing…

I never really thought about it. Arthur Jafa is a friend and we have been speaking a lot, not really collaborating but always speaking about what we do without trying to define it as such. I am glad our worlds collided via Instagram. Without him we wouldn’t be sitting here. I am always thankful that people see the value of what I am doing, although I could continue without it, it is always good to have people to share an eye with, to help me understand what I am saying through the visuals, without using the voice. He recognized this and that is something that I have never felt before. He was the first one that gave value to my work, the work spoke to him and he found it important. The very same thing happened when I saw his instagram, I had no idea who ran it, I didn’t know anything about him, but the way he put out images and how they communicated with each other really spoke to me.

Frida Orupabo, 12 self portraits, 2020. Courtesy of the artist & Gavin Brown’s enterprise New York / Rome. Photo: Roberto Apa.

Also in regards to your other practice as a social worker, what is your relation to reparation?

I have done what I have been doing also to survive, to have a continuous dialogue with myself, while doing research and finding things that all the time proves one’s own value. At my job this is very important because I work with people who sometimes lack this understanding of being valuable. For me, to understand you’re valuable, inasmuch as your life is, is a starting point. There are different ways of doing that, my way is through the visual. Some people write, some dance, some organise or create networks…

Where does the name Nemiepeba come from?

Nemi is my name. It means “god’s will” and it was given to me by my father. It’s a Nigerian name and Epeba too, but I can’t recall what it means. I just read it somewhere, I liked it and put the two together—I should try to find out what it means as you’re not the first who asked me. At the beginning I have been trying to force Facebook to work as Instagram, as you can also collect albums, and when you would be out of the album you could see all the images side by side—although no one was looking at the album. But when I found out about Instagram, I was like, okay this is it. Back then, I didn’t have many friends or family on it, so I started using it without even thinking about followers. I didn’t want it to be a space like Facebook, so I called myself Nemi—although I don’t use that name, I am Frida. Nemiepeba was a way for me to create, again, a safe space to work undisturbed.

Frida Orupabo, 12 self portraits, 2020. Courtesy of the artist & Gavin Brown’s enterprise New York / Rome. Photo: Roberto Apa.

Can you tell us something more about this urgency (both your personal and generally speaking) of making art and its constitutive healing potential?

For me personally, it’s the only field in my life where I feel I am 100% certain of what I am doing and I can be unapologetic—this is what I want to say and say it through the visuals, put it out there without being afraid. But for instance, when it comes to writing, since I was younger, if you would ask me now to write a text I would be so tense, even to write down a line. I remembered I started a diary and although I was sure no one would read it, I was so fixated with getting the correct lines, that they should be beautiful, and this always prevented me from really just feeling and getting it out. When I work with images, I am able to express myself, and I get it out in that pure sense, meaning what you feel and think in that specific moment. When the people see it or get involved in it later on, would then get the best of me. It’s something beautiful to be able to communicate through what you do, as the visual can go above what one can write or speak. It can’t be constrained, as it can be as complex as to contain so many meanings, but in some way there will still be an end to it. The visual is for me the purest form of communication, in its capacity to reach so many people in different ways, and this is its strength.

Because it leaves space for the viewer to read it?

Yes, to interpret it, to read it and to take ownership of it, like I take ownership over the material I choose to use. I am not just talking about the colonial archives, but also other artists’ work, I take it and mix it with my own stuff to create new narratives. I am thinking to have references on Instagram to keep the lineage on whom and what I am building upon—going back to what you said about being invisible and especially women in history, mentioning becomes compelling—mentioning where you’re coming from and somehow also who you are, who stands behind and beside you, or in front of you. Even though I am not a very social person in a way, I feel I am creating some kind of community and speaking from somewhere, and it can be the same somewhere somebody else is speaking from.

Frida Orupabo, 12 self portraits, 2020. Courtesy of the artist & Gavin Brown’s enterprise New York / Rome. Photo: Roberto Apa.

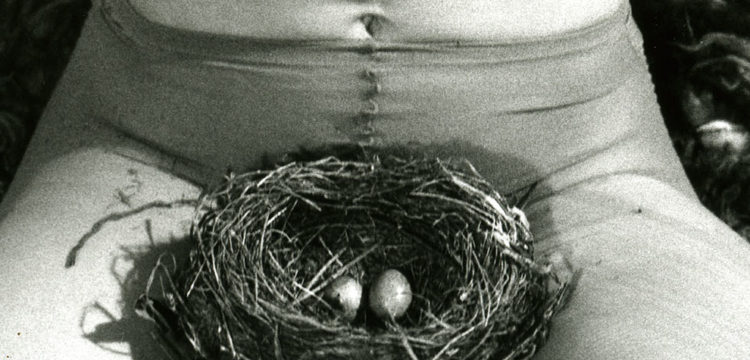

You mentioned the female body, there is this use of the erotic body, especially of the black body—where do you think a reconciliation may exist or take place between the female (black) body and the erotic sphere, meaning the use of the erotic and its representation as a suppressive tool?

That’s why I love collages, because collage is a very effective (although I hate the word effective) medium, it’s a good way of working when you want to deconstruct and create counternarratives. So, I believe the way I am working now is a way of challenging those images, take for instance the image of the black female body and how that body has been constructed as something deviant, something abnormal and hypersexual. That was also something I saw at my job—mainly Nigerian women coming to Norway working. Their experience from the streets was very different from white women’s experiences, in the way they were treated and talked about in the media and by people in general. People tossed money and food at them. They were seen as more aggressive than white sex workers. The whole discourse was just so familiar. To challenge that is difficult, but hopefully I manage to, though. I remember once I received this critique at the exhibition in Stockholm, a woman who was going to write and she didn’t feel I truly challenged it, and I find that interesting because then I have to go and revisit my work, can I stand for it or can I not? It’s hard to balance this, as sometimes you just want to make work and I do work with images of people, but it will always be seen as a woman, a black woman, then immediately trigger all these ideas. Sometimes I want to make works that shows women that pleases themselves and I want to own this feeling around this work, but I am aware of the fact that many people will have very limited ideas around it—not limited because I understand where it comes from, I do also carry these structures—but it’s always about balancing, when I work sometimes I just want to make work and I want to make what I make without attaching too much into it. So you have this image and you put another image beside it, that will change the content, change the image itself. The same happens with collages, as I often mix bodies, you see different body parts from both male and female, or I use images of women that are kind of masculine and hopefully will also change the viewer’s gaze and feelings. One piece I showed in New York was a man lifting up his leg, but I added a baby as if he’s giving birth, although he has a flat chest and it makes it very difficult to have a very straightforward story about that image or that person, and I try to solve it this way. I try to solve it until I am pleased with it, until I am confused or question the image myself.

Frida Orupabo, 12 self portraits, 2020. Courtesy of the artist & Gavin Brown’s enterprise New York / Rome. Photo: Roberto Apa.

I am quoting Audre Lorde (from Poetry is not a Luxury): “For within living structures defined by profit, by linear power, by institutional dehumanization, our feelings were not meant to survive.” I see how your layering and re-composing gives instead value to these feelings and challenges both this linearity and de-humanizing attitude. What would you say about it?

The first thing would be the importance of creating a safe space, and that would be different for each of us—what I was saying above about the Instagram, I created the profile under a name where people won’t find me easily, as a way to create a safe space, but actually also the beginning of daring to speak, or daring to put out there what I have done, whatever I am working with, which might be not directly political, but still the work becomes exposed to judgement. I love Audre Lorde, and the way she speaks of the importance of acknowledging differences—to see it, work with it and understand it as the only way to move forward. In my personal experience, my father is Nigerian and my mother is Norwegian, I was born and raised in Norway and my father left when I was three. Culturally I am Norwegian, but still people have struggled to place me, and sometimes who one is might not be appreciated in different environments. I have learnt to reduce parts of me according to each specific field. When I read Audre Lorde I recognize that she’s talking about the exact same thing. You’re not allowed to be fully who you are because of these ideas about what is whiteness, what is blackness, what is a black person, and how do you define that? All these definitions are very strictly set, you know, what is really black and what not—you might be black and really white on the inside. During my upbringing, I always got comments from both sides, and then one starts to feel quite marginalized and misplaced, like there’s really no place where you belong. This aspect is also constitutive of the things I have done, and the starting point was to create a space where I survive, or what I think is me survives, when you have all these opinions around you.

And you can have all the layers…

Yes, which are all equally important. If you manage to see the importance of that, you can understand more of other people and all of what they are when they come to you.

What is a book, or a reading list if you like, we should all read?

I have to say, I’ve been reading less since I became a mother. But I love Audre Lorde, bell hooks, Grada Kilomba—I love her in relation to growing up in Norway, because most of the literature is often African American writers and she writes more about the context of Europe and the racism experience. Ah and Gayl Jones. Nowadays I read about plants, sometimes you get tired of theory. Clarice Lispector, who’s a bit of a racist, which is sad. Usually I cross out the lines in her book and continue reading because I love her writing.