Refusal of Work as Refusal of Culture

The Conditions of a Radical Project

An excerpt from the book Global Tools 1973–1975: When Education Coincides With Life (NERO, 2019) edited by Valerio Borgonuovo and Silvia Franceschini.

The refusal of work—the most important political category of Italian workerism (operaismo), referring to the practices of Fordist workers’ fight against large factories whose assembly lines represented the exploitation of industrial capitalism—was considered by the founding members of Global Tools as the “greatest discovery of the century” and “the fundamental law of all social dynamics,”1 such that “the only progress is that which eliminates work.”2

Global Tools introduces a radical innovation in understanding the relationship between capital and society. While for workerism, society was supposed to be invaded by the logic and methods of the factory, those involved in the development of Global Tools turn this thinking on its head: “for capital it is not society which must become like a factory, but the factory which must resemble society.”3

This is a particularly appropriate method for studying capitalism at the end of the 1970s, a period in which consumerism played a central role and tended to reduce creative activity to a purely consumer activity (such that we can speak not only about the workforce but also of the consumer force). Another essential innovation particular to this group: the refusal of work also implies the refusal of culture. The former includes all of society’s moral, religious, and aesthetic meanings and values. Culture has a specific role, particularly important in capitalist society, because “a producer of role models is a part of the productive organization of society.”4

The aesthetical-political problem then becomes “freeing man from culture and art,” which means liberating people from models of behavior produced by culture that have become even more invasive with the advent of consumer society. These practices of refusal that have affected the world of salaried work as well as the domains of art or culture also anticipated the critique of “creativity” because at the end of the 1970s and the beginning of the 1980s, it would submit, like all other activities, to a process of control, normalization, and homogenization. The “creatives” have since become publicists who create “concepts.”

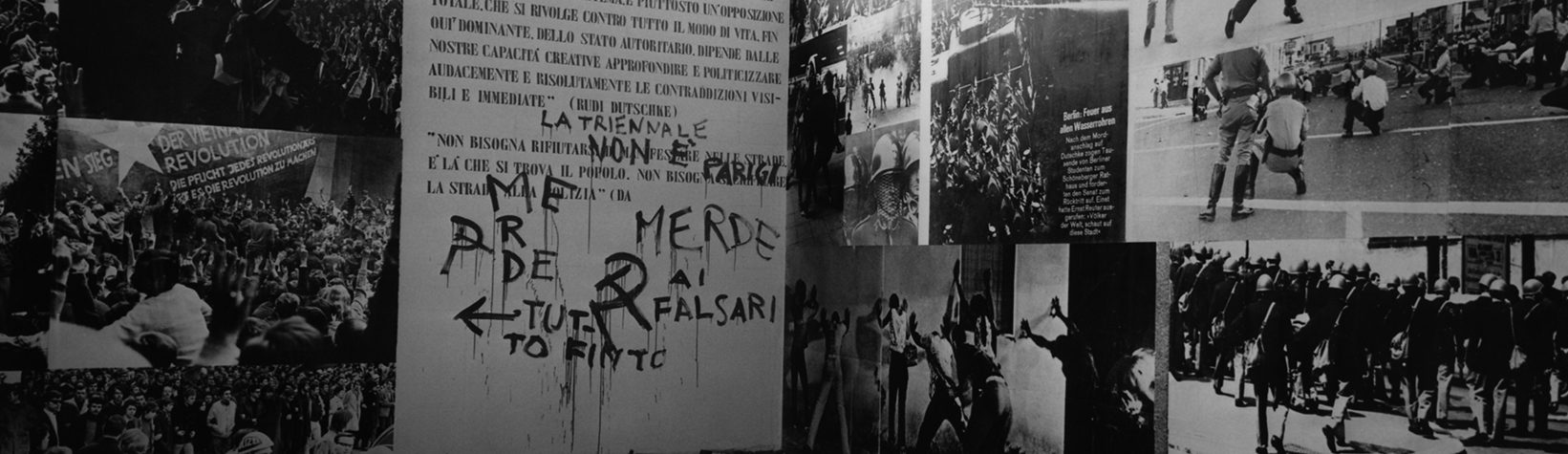

Students protest during the opening of the 14th Milan Triennale, May 30, 1968, photograph by Publifoto, courtesy Archivio Fotografico © La Triennale di Milano.

Culture (and notably, design) must accentuate the value of consumer objects by creating transitory models of behavior and pretending to provide the user a culture and a set of choices which he or she does not possess and has never made. It stimulates the action of the user inside a modular reality, that is to say a system which “ensures that the creative process must happen inside a perimeter of already predetermined combinations.”5

This brief review of the conditions of a radical project seems once more vital and relevant today. So why is it that they have disappeared from “artistic and cultural projects,” and why were these positions abandoned by speaking of the “end of the age of revolutions” and the need for a “radical reformism”?

“Creative destruction turns into full-on destruction and the future no longer holds the promise of wealth, happiness, and self-fulfillment.Growth, which must fulfill its promises, is not forthcoming and, in any case, it would be a kind of growth that deepens inequalities and distributes money and employment like a society of rentiers.”

Once the avant-garde, the age of politics and that of revolution had exhausted their strength, the possibility opened up for a “reformist civilization,” of a “radical reformism.” The model of “weak organization” and “soft” technology (electronic and digital) make a “reformist culture” possible, one that manifests itself in “continuous change” and a “perpetual transformation.” It is this thesis born in the 1980s and 90s that has not weathered the financial crisis. Continuous change and perpetual transformation collide with limits and give way, as in the current financial crisis, to an economic and cultural stagnation.

In these conditions, reformism has become impossible, if it even existed during neo-liberalism. There is no more room for social progress and mobility. The United States, which had been the mythological home of “destructive creation” and the realization of the “self-made man” is the most rigidly stratified society in the world. Creative destruction turns into full-on destruction and the future no longer holds the promise of wealth, happiness, and self-fulfillment. Growth, which must fulfill its promises, is not forthcoming and, in any case, it would be a kind of growth that deepens inequalities and distributes money and employment like a society of rentiers.

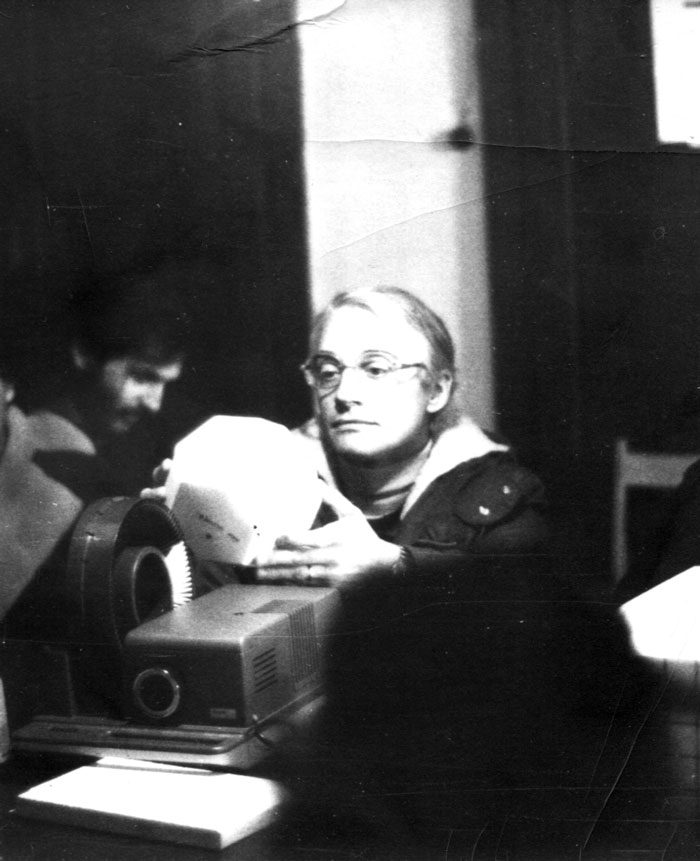

Alessandro Mendini with a paper dodecahedron during one of the Theory Group sessions, first Global Tools general seminar (November 1–4, 1974, Sambuca Val di Pesa, Florence), courtesy Piero Brombin Archive, Luvigliano di Torreglia (Padua).

Reformism is impossible because the single largest reformism practiced by capitalism to get out of the stock market crash of 1929 (the New Deal), presupposed neutralizing “finance,” or what John Maynard Keynes called the “euthanasia of the rentier.” In a “financialized” society like ours, neutralizing finance means neutralizing capital. This is why regressive policies are being adopted to get out of the current crisis; these are not short-term but structural policies which turn democracy towards authoritarianism. The crisis is not only economic, it is also a crisis of our model of civilization; it touches on and refers to livelihoods, not only that of humans, but also non-humans (the environmental crisis).

The need for a critique, a break, a refusal becomes a prerequisite not only in politics, but also in aesthetics because the assertion made by Archizoom Associati in the 1970s is still relevant: “It is impossible to give a different definition of creativity without imagining a different social reality, in other words, without supposing a non-productive end to creativity.”6 Weak organization, soft technologies, and radical reformism are precisely the techniques that put creativity to work for valorization of capital. The condition of creativity is still, however, a society without work where salaried work is abolished. In these new conditions, the refusal of work is not a “dialectical” expedient, quite the opposite. Among the multiplicity of reasons which push us to retain and redefine the concepts of refusal of work and refusal of culture, let us examine two: the impossibility of reformism in post-financial crisis capitalism, and the possibility of practicing “refusal” (of work) in previously unseen forms, in other words, they must also and especially apply to “creative,” “artistic,” and cultural work.

“The workers’ movement only existed because the workers’ strike was simultaneously a refusal, a non-movement, a radical form of idleness, and inaction; a work stoppage which suspended the roles, functions, and hierarchies of the division of work in the factory.”

We have the possibility to make it effective again, not only because the influence of capital on our lives has not ceased to grow but also, and especially, because we have not exhausted all the resources which refusal holds. While simultaneously opposing, critiquing, and fighting the capitalist organization of society, refusal is also, and especially, a form of self-expression, and an expression of new forms of subjectivity and new values.

The workers’ movement only existed because the workers’ strike was simultaneously a refusal, a non-movement, a radical form of idleness, and inaction; a work stoppage which suspended the roles, functions, and hierarchies of the division of work in the factory.

Theory Group session, first Global Tools general seminar (November 1–4, 1974, Sambuca Val di Pesa, Florence), unknown photographer, courtesy Ugo La Pietra Archive, Milan.

Problematizing only one aspect of the struggle, the dimension of the movement, was a major handicap that turned the trade union movement into an accelerator of productivity and industrialization, the champion of labor. The other dimension of the struggle involving the “refusal of work,” the non-movement, or demobilization has been neglected or is not a priority issue in neoliberalism.

Even the analysis implemented by the members of Global Tools avoids equating the power of “demobilization” and non-movement with the non-productivist temporalities of the refusal of work and culture. The result of these practices is that the refusal of work forces capital towards automation and the creation of more free time, on one hand, while the claims related to the refusal of work (higher salary and fewer work hours) destroy the economic logic of capital, on the other.

Workers’ refusal of work always refers, in this regard, to something other than itself. It refers to politics, to the party or the State, where it refers to new conditions of production and consumption patterns (automation and free time). But if, instead of referring to something else, one looks at the refusal itself, at the non-movement, at the demobilization it contains; if one works to deploy and experience all that the action of refusal of productivist logic makes possible, one can then convert subjectivity, invent new techniques of being, and a new way of living in time. The feminist movements, after their refusal to perform the functions (and work) of “women,” seem to have followed this strategy, rather than the classic political option.

The anthropology of workers’ refusal remains, however, an anthropology of work, and the subjectification of class is still a subjectification of “producers,” and of workers. The action of refusal is open to any other anthropology and to all other ethics. By eroding the foundations of “work,” it undermines not only the identity of the “producers” but also their sexual assignments. What is at stake here is the anthropology of modernity: the subject, the individual, freedom and universality all combined in the masculine.

1 Andrea Branzi, “La Gioconda senza baffi,” in Moderno postmoderno millenario: Scritti teorici 1972-1980 (Turin/Milan: Studio Forma/Alchymia, 1980), 10.

2 Archizoom Associati, typescript from Archizoom Archive, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Centre Pompidou, Paris.

3 Andrea Branzi, “Abitare è facile,” in Moderno postmoderno millenario, 25.

4 Andrea Branzi, “Mass Creativity,” in The Hot House: Italian New Wave Design (London: Thames and Hudson, 1984), 81.

5 Branzi, “Abitare è facile.”

6 Archizoom Associati, typescript from Archizoom Archive, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Centre Pompidou, Paris.