Primal Screen: Decolonizing Cinematography

A conversation between Silvia Franceschini and The Otolith Group

Silvia Franceschini discusses with The Otolith Group’s Anjalika Sagar and Kodwo Eshun the making of their film Infinity minus Infinity (2019). The film brings together dance, music and digital animation to compose a transhistorical cinematic zone that weaves together the unpayable debts of slavery and colonialism, the contemporary politics of citizenship and the ongoing climate catastrophe. INFINITY minus Infinity addresses the discriminating policy of “hostile environment” enacted by the UK’s conservative government towards those Afro-Caribbean communities which settled in Britain and helped rebuild the country’s industrial infrastructure after the Second World War. Inspired by Black speculative fictions and cosmologies, a chorus of deities allude to times and spaces within the United Kingdom’s environmental and racial hostility, inscribed in financial districts’ mirrored buildings reflecting the sky, along the obscure ongoing extractions in neocolonial offshore tax havens.

INFINITY Minus Infinity by The Otolith Group was commissioned by the Sharjah Architecture Triennial SAT01 and co-produced with Z33 House for Contemporary Art, Design and Architecture, Hasselt for the exhibition Le Déracinement. On Diasporic Imaginations (2021) curated by Silvia Franceschini.

The Italian translation of Kodwo Eshun’s More Brilliant than the Sun (Verso Books, 1999) is forthcoming for Not in October 2021, with the title Più brillante del sole. Avventure nella fantasonica.

Silvia Franceschini: I’d like to start from the beginning of INFINITY minus Infinity. How did the idea of the film come about?

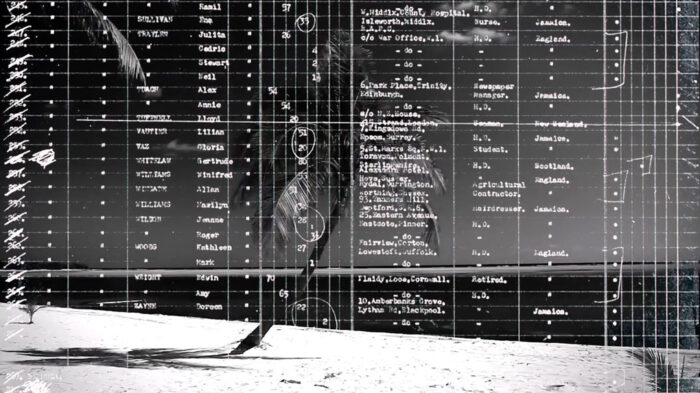

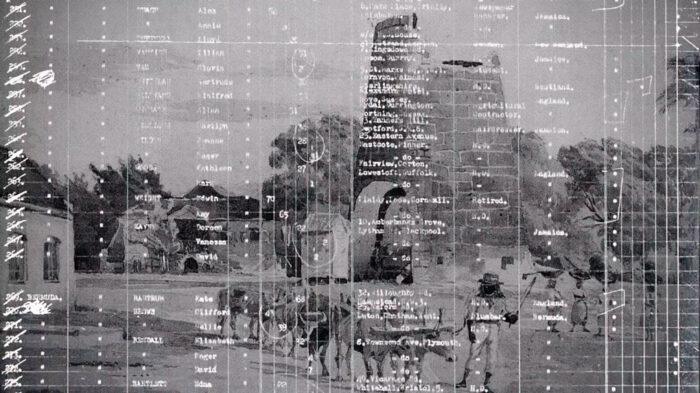

Kodwo Eshun: One impetus for INFINITY minus Infinity emerged from a desire to speak to specific political events in Britain and to the larger questions that informed those events. The so-called Windrush scandal plays a critical role, for us, because we see its intent and its aim as a direct attack upon the generation of New Commonwealth settlers of the 1940s and the 1950s. That generation was the last to accept the idea of England as the so-called Mother Country. The last to share common ground with the respectable white British working classes. To deprive those citizens of their citizenship is to attack the very existence of black generational settlement itself. In the process of researching the so-called hostile environment policy imposed by the Tory government in 2012, we began to grasp the extent to which the Windrush crisis could be understood as a moment in an ongoing process of bipartisan unsettlement. As we situated the hostile environment within the legal infrastructure of imperial and post-imperial Britain, we encountered the so-called Friday Fact tweeted by the Treasury in 2018. That tweet informed the British public that their taxes helped the British state, in 2015, to pay off the £20 million loan incurred by the British government in 1833 to compensate the 64,000 slaveowners for the abolition of slavery in the Caribbean. The greatest bailout in history went to the wealthy slavers; the former enslaved received nothing. Thinking the crime of slavery, the crime of compensated emancipation and the crime of repayment together with that of the Windrush scandal began to give us an understanding of the afterlife of slavery in its British context. Saidiya Hartman formulated the notion of the afterlife of slavery in 2007 in order to account for the ways in which “black lives are still imperiled and devalued by a racial calculus and a political arithmetic that were entrenched centuries ago.” What we began to comprehend were the forms of disavowal and foreclosure specific to Britain. INFINITY minus Infinity tries to create a post-cinematic encounter with the texture and the character of méconnaissance in Britain. This requires us to distance ourselves from the kind of documentary that invites those that have endured this kind of criminalization to narrate their suffering for the cameras. It is a matter of inventing other means and other methods of aesthetic justice.

Anjalika Sagar: When we talk about aesthetic justice in this context, it is not so much a question of speaking to the Windrush generation but of finding ways to speak to and with contemporary generations. As the historian David Olusoga says “a new generation doesn’t understand that their history is being destroyed within this.” What we wanted to do was to make a work in which theory feeds into the realm of the aesthetic. We wanted to invoke a mutant cultural space that explored the politics of the present in its relation to the cultural forms that bind the UK to India, the Caribbean and West Africa. We wanted to make a work that would bring the hostile environment into relation with what we call environmental hostility. We wanted to challenge a certain agnosia and a kind of amnesia by evoking memories held within bodies. That’s one reason we use the digital to activate the senses as portals for areas of experience.

The film borrows its title from Denise Ferreira da Silva’s formulation of an “equation of value” that informs what you call the “aesthetic imagination of blackness as that which holds and hosts the capacity to disrupt life.” What does it mean for you to think with black feminist poetics and cosmologies?

Anjalika Sagar: Denise Ferreira Da Silva was an important inspiration for this project. When I met Denise many years ago, I felt that she was a brilliant theorist that was extremely involved in the struggle of what it means to be alive on an everyday level and finding healing mechanisms to help with that struggle. What Denise is saying in the Equation of Value is that the total extraction of value from slavery is what made possible Western culture, civilization and humanism. What Denise’s ideas give you is the sense that Western institutions’ relationships with blackness is an ameliorative project to redeem itself. What that leaves you with is refusal. You have to produce an aesthetic that enacts this refusal. That requires resistance to the absence of ruins of these crimes. You can remember those crimes, as Saidiya does, through citation. The act of citation brings together an infinity of traces in order to maintain, not just memory, but practice. I would say that our aesthetics are informed by practices that have been involved in this project. This has to do with the cosmological, which for me is a question of energy that is life before its extraction. Life is what is produced when you listen to Pharoah Sanders or Alice Coltrane. Sonic life that produces a desire to think and to remember what made this possible. I think that the sense of the cosmic is a space in which to say “let us think inside this space because this space is our inheritance.” This space is one which we can project into, a space from which and within which one can carry on producing thought.

INFINITY minus Infinity makes use of digital animation, and somehow it seems generally different from your previous works. How did you carry on such aesthetic choices concerning the visual aspects of the film?

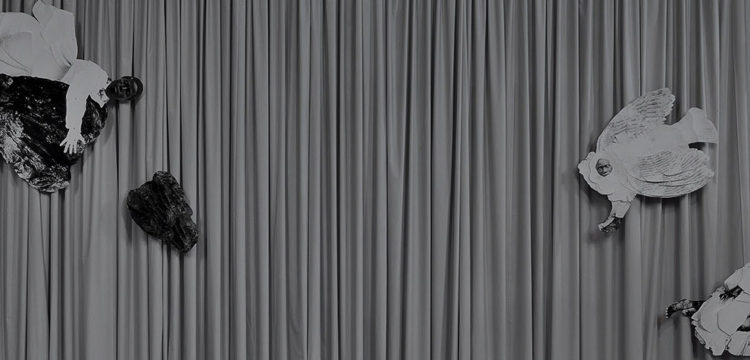

Kodwo Eshun: We are preoccupied with dissimilitude, with the ways in which a new work does not resemble the previous works. There are at least three kinds of aesthetics in INFINITY minus Infinity. There is green screen or chromakey, there is digital animation, and an engagement with a deep focus enabled by the use of the shift and tilt or tilt-shift lens. What is specific about INFINITY minus Infinity is the aspiration to bring these aesthetics together to create a certain kind of extra-temporal space. A space from which to comment upon specific dates such as 1610, the year of the so-called Orbis Spike; 1833, the year of the non-event of the abolition of slavery; 1948, the year of the British Nationality Act or 2030, the date set by the Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change for the reduction in global net human-caused emissions of carbon dioxide. This is not to say that the entities that reappear throughout INFINITY minus Infinity can be situated within these specific dates. They seem to inhabit an extratemporal dimension outside of chronology. Chromakey allows you to create post-cinematic landscapes that comment upon existing conditions without being contained by those conditions. We are trying to evoke an aesthetic of interscalar travel in which discrepant entities move across discrepant scales. The idea is to think of the digital work as an interscalar vehicle.

Which kind of manoeuvres become possible for a film conceived as an interscalar vehicle?

Kodwo Eshun: We’re trying to think about what it means to change claims as we move across scales. What kind of discrepant claims become possible when you travel from the age of the Orbis spike that marks the Spanish genocide of the indigenous population in the Amazonian Americas from 54 million in 1492 to approximately 6 million in 1650 to the future of 2030 threatened by the global increase in carbon dioxide? When you speak of the non-event of the abolition of slavery in 1833? Such claims require you to calibrate the dimensions of a metamorphic imagery. This interscalar aesthetic is part of an effort to think through what Dipesh Chakrabarty calls the climate of history.

There is a very distinct lighting in the scenes with the actors. How did the skin tone of protagonists affect your approach to cinematography?

Kodwo Eshun: There is a specific relation between lighting and makeup and skin tone in the scenes with Dante Michaux and Elaine Mitchener. We were influenced by cinematographers such as James Laxton who worked on Barry Jenkins’ If Beale Street Could Talk (2018), Moonlight (2016) and The Underground Railroad (2021) and Bradford Young who filmed Ava DuVernay’s Selma (2014) and When They See Us (2019). That numinous imagery, which you see in those films, in which skin tones are chromatically illuminated, that is what we call devotional cinema, which is aesthetic justice, an aesthetics of repair. The chromatic movement that travels across the landscape of the faces of Dante and Elaine is something that we discussed a lot with our cinematographer Kate McDonough. If you are working with Afrodiasporic skin tones, you have to be conscious of the aesthetic injustice committed by cinematography, before, throughout and beyond Hollywood. You have to comprehend the coloniality of cinematography in which the use of film stock, lenses, lighting and makeup subjects Afrodiasporic to a cinematographic exorcism and a chromatic denigration. Every artist that works with cinematography is obliged to develop a critique of the institution of cinematography. When we encountered Elaine Mitchener and Dante Michaux, both of whom are great artists in their own right, their presence made it possible for us to advance these cinematographic ideas that we had been discussing for a long time.

What did the script writing process for such a multilayered work look like?

Anjalika Sagar: As a series of ideas that emerged from many conversations. From visions, traumas and experiences. There are things in the world that speak to you directly. For a long time, there was a lot of speaking and thinking going on which became a matter of storyboarding. Asking the various researchers in INFINITY minus Infinity to perform their research so their voices and their thinking could be inscribed inside the work. We recorded specific voices to evoke ASMR or Auto Sensory Meridian Response. Discovering ASMR made me realise the degree to which technology could heighten the role of the sound to direct the gaze within the frame.

Kodwo Eshun: Esi Eshun, Vivian Latinwo-Olajide and Angela Chan each researched specific aspects of the project for which they wrote texts rather than scripts. We asked them not to act but to read their texts with a certain intensity. There is a lot of speech in INFINITY minus Infinity but each kind of utterance does a different kind of work with a different kind of effect.

The idea of looking at a racial formation of geology is something that INFINITY minus Infinity shares with Kathrin Yusoff’s book A Billion Black Anthropocene or None. Kathryn Yusoff herself also appears in the film. Could you explain how you have engaged with Yusoff’s work and with the idea of earth and geology as a medium?

Kodwo Eshun: I had read A Billion Black Anthropocene or None as soon as it was published. What was important was the way in which Yusoff analysed the coloniality of geology by drawing on concepts elaborated by black feminist theorists such as Sylvia Wynter and Saidiya Hartman, the writings of black feminist poets such as Dionne Brand and black feminist science fiction such as N.K. Jemison. Yusoff formulated a vocabulary for a decolonial critique of the Racial Capitalocene. We asked everybody involved with INFINITY minus Infinity to read Kathryn’s book. You can see and hear that Kathryn’s responses are drawn from her book but are delivered in a different tone, a different key, you might say.

Anjalika Sagar: An earlier Otolith work such as Medium Earth (2013) speaks of the geologic time of boulders, deserts, faultlines and hairline cracks. It looks at the ways in which wind writes, weathers the lithic and writes on stones. It tries to frame images and record sounds from the perspective of mineral life and tectonic faults.

Could you tell us about your exploration of the notion of “environment” as a climate of anti-blackness that is politically and historically instituted?

Anjalika Sagar: That idea of a pervasive climate of hostility evokes those sentences from In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (2016) when Christina Sharpe argues that “the weather is the totality of our environments; the weather is the total climate; and that climate is antiblack.” That idea of the total climate of antiblackness offers a vocabulary for thinking through the ways in which the extraction zones of the Racial Capitalocene are indivisible from the genocides of racial capitalism. They are linked; they have always been linked.

Kodwo Eshun: What INFINITY minus Infinity aims to formulate a project in which the practice of environmental hostility is inseparable from that of the hostile environment. It is a matter of compounded violence that is slow rather than spectacular. We are trying to attend to the slow temporalities of compounded silences.

INFINITY minus Infinity unfolds in an exhibition space as an immersive environment, a blue room that expands the experience of the film in the physical world. What do you achieve by putting a spectator into a deep cinematic space constructed around the film?

Anjalika Sagar: We enjoy the feeling of sustaining a space that is produced by the light of the screen. I think the screen invites you to enter into an experience of time under specific conditions. It evokes the sense of sitting in the control room of a spaceship, of looking out of a starboard window. Those kinds of sensations fed into the blue of the space of encounter with INFINITY minus Infinity.

Kodwo Eshun: Working with Diogo Passarinho on Xenogenesis for the last two years has enabled us to experiment with the processes of extending a world in several dimensions. It is not only that the space of spectatorship emerges from your experience with the screen; it’s a matter of creating a sensorial invitation that holds you in the time and the space of a design fiction.

The film brings together voices of different Carribean thinkers such as Una Marson, Sylvia Winter and Édouard Glissant. How would you define the role of Caribbean culture for your work?

Anjalika Sagar: Caribbean poetics, in all of its modalities, have shaped our formation. So much of London, at its best, is a kind of Caribbean transplantation, in its structure of feeling—sense. What is specific to INFINITY minus Infinity is its emphasis upon a translational aesthetic of Caribbean discourse.

Kodwo Eshun: Once you decide to focus on the afterlife of slavery in Britain, that requires you to focus upon the political implications of Caribbean poetics. It is the thinkers of the Caribbean that have produced the most far-reaching critiques of capitalism and slavery in Britain. The argument is that the poetry written by Una Marson in the early 1930s provides a vocabulary for comprehending British coloniality that anticipates that of Fanon in France in the early 1950s. We are rereading Una Marson’s poems for their attention to the environmental hostility of 1930s London.

Anjalika Sagar: I think of the Caribbean archipelago as an intellectual world remade by the Racial Capitalocene, a world that has, and continues to, produce a vocabulary for transformation, a language for undergoing metamorphosis and a language for transplantation; each of which provide, in turn, the vocabulary for an aesthetic justice.

The Otolith Group works with a type of political film aesthetics that Deleuze would call “pedagogical” in reference to his idea of a “pedagogy of the image” a form that thinks through transmission, encounter, retention, and repetition. Where does your interest in pedagogy come from?

Kodwo Eshun: We have a passion for pedagogy removed from strictly disciplinary structures. I think that offers one way of understanding the essayistic impulse. A pedagogy separated from a curriculum that has a capacity to function as an instituting practice. Like you see in the efflorescence of reading groups around Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study (2013) or reading Cedric J Robinson’s Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition (1983). Reading groups are an instituting practice without tutors or students. Perhaps this desire for pedagogy comes from a primal screen that is not so much cinematic as it is televisual. It comes from having an encounter with world cinema, at the end of the 1980s, in London, at a young age, that has exceeded its institutional framework. It’s just you, watching Stalker, on television, at 11 pm.

Anjalika Sagar: In the first decade of Channel 4, between 1982 and 1992, there was a political will to enable independent filmmakers from all parts of Britain to make documentaries combined with a project to broadcast films from India, North Africa, West Africa, South Asia, Latin America. In that decade, television functioned as a space which seemed to be much more dynamic than the museum or the gallery. Those spaces seemed to impose strict protocols for behavior and comportment. By comparison, television seemed to enable discussions that happened outside of the so-called art world. If these kinds of experiences with television constitute your formative encounter with the screen, then you will be dissatisfied with much of what the artworld celebrates under the sign of moving image. You are always wrestling with those definitions, always making demands on moving images, always asking it to do more, to do better. I think the essayistic emerges from this tension, this discrepancy and this disappointment between what moving images and sounds are, what they could be and what they should be.